2

“Proletarians of all countries, unite!”

– Fredrich Engels & Karl Marx 1848

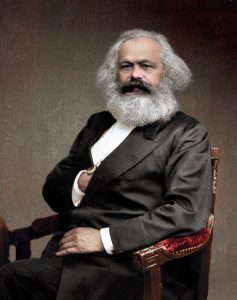

The journey through revolutionary study starts with the most influential revolutionary theorist in the field, Karl Marx. His work influenced the proceeding conflict scholars, making his work inseparable from the study of revolution and political violence. Although many of his now-known Marxist theory applications failed to occur, the core ideas Marx introduced are still significant contributions to the field of political science. His work was one of the first to understand and account for the social conditions responsible for revolutionary situations and outcomes. By doing so, Marx created a foundation for proceeding scholars who would build on his ideas to explain why revolutions occurred. For this reason, it is essential to start with Marx when studying revolutions, as many core components of his theory will continue to reappear in the works of countless theorists after him. In this chapter, Marx’s ideas will be introduced and used to analyze two relevant case studies, the Algerian Revolution, and the Vietnamese Revolution. As two former French colonies, these revolutionary situations parallel each other in ways that align with Marx’s class conflict theories, dialectical materialism, and radical elites’ role.

Introduction to Marxism

At its core, Marxism attempts to understand society from a scientific perspective to create a predictive framework to analyze human history. In doing so, Karl Marx outlined his view of the human condition’s history through a rough timeline based on historical materialism. In the view of Marx, history divides into different eras, the era of primitive communism (10,000 BCE), slave society (7,000 BCE-500 CE), feudal society (500-1600 CE). Finally, he claimed capitalist society began in 1600 CE and would end in the early 20th century. From the era of “primitive communism” to the current era of global capitalism, Marxism maintains the fundamental assertion that history invariably contains opposing power differentials between classes of people (Hudson, 1959). Marx has even gone as far as to argue that “the history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles” (Marx, 1848 p. 57). Marx argued this because Marxism is heavily rooted in the Hegelian dialectic.

Dialectics is a philosophical exercise that focuses on opposites’ unity through the conflict between two opposing groups, the thesis, and the antithesis. According to Hegel, the thesis and the antithesis can engage in conflict to form a new social paradigm. Hegel referred to this as the synthesis. When discussing dialectics, the thesis will represent a socially dominant group, while the antithesis represents a socially subordinate group. This concept is quite abstract, so it helps to look at an example. For Marx, the primary dialectic that affected him and his contemporaries most directly took place between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Since the bourgeoisie holds far more power than the proletariat, the bourgeoisie will represent the thesis, and the proletariat will represent the antithesis. By recognizing this relationship, Marx expanded on Hegel’s original concept of the dialectic by combining it with his historical materialism idea, creating dialectical materialism. This where the scientific aspects of Marx’s view of history come to fruition. With this understanding of history, certain conclusions can be made about a society based on its material conditions.

Marx’s theory’s central point is that society splits into two classes, the bourgeoisie, and the proletariat. One of the main talking points of Marx’s manifesto is the class struggle. The bourgeoisie controls the means of production and therefore has disproportionate control over political and economic institutions. For this reason, they are the dominant economic class. This class has been the product of historical feudalism, which we have seen throughout time and will continue in this state. The bourgeoisie will continue to gain capital by exploiting the proletariat by owning and selling the proletariat products. A capitalist society with a global free market allows for the growth of the bourgeoisie. According to Marx, they can exploit the market for their growth, with their main goal being maximization (Marx, 1848). This sets up a society driven and motivated by money, which provides society with safety and dignity. Marx sees this lifestyle as a problem arising from capitalism as money becomes a way to evaluate each other and ourselves. (Marx, 1848).

The proletariat, on the other hand, is oppressed. The proletariat was made up of the working class and worked for the bourgeoisie, who benefitted from the proletariat’s labor. Although the proletariat was the lower class within society, Marx sees this class with the power to overcome the bourgeoisie. The proletariat had the numbers and potentially the power to rise against the oppressor. Marx also speaks of how the proletariat will continue to grow in numbers due to the ever-expanding bourgeoisie class. As the bourgeoisie continue to expand and revolutionize their production means, this will eventually drive the smaller tradesmen and self-employed to join the proletariat class as they cannot compete with the true bourgeoisie (Marx, 1848). Moreover, as the proletariat continues to expand in size, members of the bourgeoisie see this expanding class and decide to switch over to avoid the inevitable outcome of a working-class revolting against the bourgeoisie. However, the bourgeoisie cannot survive without the proletariat as they are the producers of their capital. Hence, the bourgeoisie continues to keep the proletariat at a length where the working class can survive but never more than this (Marx, 1848). Although Marx argues the harm in a capitalist society, his work argues that capitalism creates the opportunity for communism to arise as the increase of class inequality and the proletariat’s global togetherness due to similar capitalist conditions worldwide. Both of these factors help contribute to the rise of communism. (Marx, 1848). All of these various factors within a capitalist society move towards an end goal, which is communism.

Marx also speaks about the idea of labor value. Marx believed that workers should be paid based on their output and the number of hours taken to produce a specific product (Marx, 1848). Marx identified that the bourgeoisie often made the working-class work long workdays while producing goods worth a significant amount of money. However, instead of receiving a wage relative to the number of goods produced within the hour, the workers will have received an amount of pay set by the factory owner, which did not reflect output. For Marx, a fair representation of their work would emulate the amount of work done with the amount paid (Marx, 1848). However, since labor value is only a theory, the reality was quite different within the bourgeois rulership. Since the bourgeoisie owned the factories and the labor force, they used free trade to their advantage. Their use of free-market capitalism allowed the bourgeoisie to expand their wealth as they could create more significant profit margins by keeping wages low. Additionally, by setting the prices for the products made, the factory owners would do their best to gain a competitive advantage over the market competition by lowering costs and maximizing output. The latter ultimately affected the workers due to the harsh working conditions these factory workers would often be made to work in (Marx, 1848). All these factors combined with continuing to boost the bourgeoisie’s wealth and increase the class gap. While on the other hand, these same factors would also be, according to Marx, the downfall of the bourgeoisie as these conditions within a capitalist society would force the proletariats to come together for this communist revolution (Marx, 1848).

Marx’s Theory of Revolution

According to Marx, a revolution occurs when two classes within a society compete for control over the means of production. This relationship has occurred throughout several historical stages, from Greece and Rome’s classical aristocracies to feudalism and Marx’s industrial capitalism era. In each of these stages, the class in control of production (masters, lords, capitalists) is challenged by the exploited underclass (slaves, serfs, and the proletariat) in a revolutionary process that results in a new political and economic Superstructure. This process is known as dialectical materialism, and Marx argued it was a predictive formula for understanding the progression of economic and political history. Taking this formula and applying it to his age, Marx presents many claims regarding how human society’s future would develop. Central to this is the clash between the proletariat and the capitalist bourgeoisie, which Marx argues will result in the proletariat class overthrowing the capitalist institutions within society, and ultimately replacing them with a communist society free of hierarchical dominance. While his theory has been far from perfect in predicting the specific events of revolutions that have occurred since publishing the Communist Manifesto in 1848, this does not mean his works were not influential. (Marx, 1848)

As one of the first political philosophers who contemplated how material conditions influence revolutions, Marx pioneered a whole political science discipline and inspired countless thinkers after him. Structuralists, like Barrington Moore and several of his students, have expanded on a concept first presented by Marx that is central to his understanding of revolutions. As he put it in the opening remarks of the Communist Manifesto, “In a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted… fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstruction of society at large or in the common ruin of the contending classes.” Here Marx argues that revolutions result from the social and economic structures present within a society, and structuralist thinkers after him understand this to be the primary cause of revolutionary situations and outcomes. In addition to those who heavily draw on Marx’s theories, even scholars who do not accept a strictly structuralist interpretation of revolutions are influenced by his arguments. For example, professor and theorist Ted Gurr gives more attention to the individual and personal factors present within societies that lead to revolution. One of the defining distinctions between Gurr’s three stages of revolution is contingent on the level of dissatisfaction elites have with the current regime. This idea is clearly influenced by Marx’s arguments from the Communist Manifesto regarding the ‘petty bourgeoisie’ in revolutions. Marx acknowledges how the nature of bourgeois society constantly threatens the status of the petty bourgeoisie. For this reason, he argued it is natural to have “these intermediate classes… take up the cudgels for the workings class”. Ultimately, Marx’s ideas presented in the Communist Manifesto were some of the earliest attempts to account for the social factors that lead to revolutions. Any analysis of a revolutionary situation or outcome is incomplete without his contributions. (Marx, 1848).

The Algerian Revolution in Relation to Marx

The French rule of Algeria began in 1830 and lasted until the conclusion of the Algerian revolution in 1962. During this time, Algeria was controlled by a minority population, divided into sections, and directly administered by the French government (Jean, 1962). Over the decades in which France had control over Algeria, there had been a tenuous relationship between the Muslim Alger people and their French counterparts. There were attempts to engage in reforms such as the 1947 Organic Statute, which aimed to give the French and Algerians 50/50 representation in the governing of Algeria. However, this action failed because the nine to one Muslim Algerian majority that made up the country viewed the action as an unacceptable half-measure (Lilley, 2012). While instances of reform occasionally graced French Algeria, events such as the 1945 Setif Massacre are better remembered by the ethnic Algerians. On May 8th, Victory in Europe Day (VE Day), demonstrators took advantage of the celebrations taking place in Setif and Guelma to march in support of Algerian independence. In response, the French police confiscated banners and even went as far as to fire upon protesters (Cole, 2010). This sparked massive riots in the cities that led to direct attacks on pieds-noirs, resulting in 103 deaths (Lilley, 2012). In a retaliatory effort, French forces went on to kill thousands of Algerian Muslims (Hitchens, 2006).

The next aspect of the Algerian revolution that needs to be explored is why it occurred in the first place. While speculation on this topic is likely endless, and many views should be analyzed, the main focus here is on the Marxist perspective. Although in many ways, the ideas of Marx are not entirely applicable to Algeria’s conditions, some of the larger themes of Marxism do translate quite well. Marx had a fascinating view regarding the role of the middle-class in developing a revolution. In his eyes, society’s material conditions need to be optimal for a revolution to occur successfully within it (Marx, 1848). For example, Marx would have argued that the peasants of a feudal society would not have been equipped for revolution in the same way that the proletariat or the middle-class could. They would have had neither the means nor the class consciousness needed for such an act. For Marx, revolution leading to socialism must be made on the back of a rising middle-class with class consciousness and a value system conducive to revolution (Marx, 1848).

Although he held many similar views to Marx, the neo-Marxist sociologist Barrington Moore expounded upon and criticized Marx’s view of the middle-class and revolution in a way that makes it more relevant to the modern world. He maintained that the emergence of a middle class within a society is one of the key aspects for pushing society towards revolution. However, he also mindfully included urbanization, increased commercial, economic activity, and the technological revolution in his analysis (Moore, 1976).

During the French rule of Algeria, the middle-class played a massive role in fomenting the revolution. The Algerian middle class was personified in the values, an emerging class of young, educated, and middle-class people (Sivan, 1979). While this group was not calling for revolution or even for an independent Algeria, they mainly advocated for representation in the government and more democratic society (Lilley, 2012). However, with this social class came ideas like liberalism and democracy, ideas that would contribute to the brewing of a revolutionary situation. This is essential to Moore’s view, who went beyond Marx to argue that the emergence of a middle-class that held values ideas like liberalism, democracy, and nationalism are vital to revolution (Moore, 1976).

Marx’s ideas can also be applied to the relationship between the Pied Noir and the Muslim Algerian population. While the Muslim Algerian population outnumbered the Pied Noir nine to one, the Pied Noir acted as a higher class within French Algerian society (Lilley, 2012). These social classes acted as opposing forces in dialectic the same way Marx would say the proletariat and bourgeoisie do. Although the Pied Noir did not have the same control over the Muslim Algerian people as do the bourgeoisie over the proletariat, they are similar in that they both represent a thesis and antithesis. A new social order developed through the conflict between the two groups and eventually revolution against French control. This represents the synthesis of the dialectic. This new synthesis will then be challenged by its antithesis, starting the cycle over again. While Algeria has been an independent state since July 5th, 1962, and the problems they faced during French rule is over, Algerian society’s current iteration faces its own internal conflicts as all societies do.

The Vietnamese Revolution in Relation to Marx

In addition to their colonies in Algeria, France controlled territory in what is now Vietnam. However, for the Vietnamese people, the French were just one of several foreign occupiers the Vietnamese have been forced to endure throughout the centuries since the first Chinese invasion. Before French rule, Vietnam was extremely rural, with an economy primarily based on rice farming. After Chinese rule ended in the late 19th century, the Vietnamese economy began rapidly changing as the French colonial government sought to enrich their countrymen by establishing industries perpetuated by the extraction of the untapped natural resources, they found themselves in control. Because these nascent enterprises relied on Vietnam’s natural resources, their social and economic impacts varied due to the geographic distribution of these resources. The North of the country, which has mineral reserves and a sizable labor force, is where most of the industry is concentrated.

On the other hand, due to French policies, the South was more agrarian with a small class of landowners in control of the majority of productive land. While a small portion of the native Vietnamese population experienced economic gains from French rule, most of the population simultaneously worked more demanding lives while their material conditions worsened (DeFronzo, 1991). The economic difference between the North and South was extremely influential in the growing political divide between these sides, culminating in the conflict between the communist North Vietnamese and the Republic of Vietnam backed by the West.

While some aspects of Marx’s theory of revolution do not entirely explain the Vietnamese Revolution’s finer details, many of his theory’s broader elements are applicable in explaining both sides’ ideological and economic identities. For example, Marx’s ideas on class conflict go a long way in explaining both sides of the conflict’s composition. After Vietnam officially split along the 17th parallel through the 1954 Geneva Accords, the country’s division occurred physically and socially. The South was initially led by the former Emperor Bao Dai, who undeniably represented the colonial era’s wealthy elite. At the time, President Eisenhower even acknowledged this when he said, “Bao Dai, who, while nominally the head of that nation, chose to spend the bulk of his time in the spas of Europe rather than in his own land leading his armies against those of Communism” (Eisenhower, 1955). Many other wealthy and landed Vietnamese were concentrated in the South as well. Additionally, this government, led by the wealthy Vietnamese elite, was backed by the Western powers like France and the United States (USDS, 2013). For the North, the new Southern Vietnamese Republic represented the old imperialist and capitalist regime with interests in preserving the existing economic order that oppressed and exploited the majority of the Vietnamese people.

Marx’s theory of revolution explains how French colonial rule transformed the material conditions of Vietnam, resulting in a revolutionary situation in which a radical elite and an oppressed working work together to overthrow the ruling class and its institutions. Marx would likely characterize political leaders in the North as the ‘petty bourgeoisie’ because although they often came from wealthier families than most other Vietnamese, their politics reflected the nationalistic and revolutionary sentiments shared by many Northerners who wanted an end to the old colonial regime. One of the most prominent figures who embodied the radical ‘petty bourgeoisie’ of the North was Ho Chi Minh. Like many of his compatriots, Minh came from a wealthy family and received a western education. During his time learning in the West when he became increasingly radicalized and was inspired by revolutionaries of the past, like the American Founding Fathers, as well as those of his time like Vladimir Lenin. While Minh was abroad, Vietnam remained under French rule despite growing frustration among the people. However, once Japan established control over French Indochina during the Second World War, Minh returned to his homeland to resist the new occupation by establishing a guerrilla unit known as the Viet Minh. Once the Japanese occupation ended following the allied victory, the Viet Minh continued fighting for self-determination against the French, who attempted to reassert control by the colonial government (Vietnam’s Revolution, 2007). For this reason, Minh’s revolutionary motivation was as much, if not more of, a struggle for independence as it was a struggle against economic oppression. Still, Marx’s theory of revolution is useful in explaining the series of events and conditions that resulted in a revolutionary situation in Vietnam.

Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism

The realization that Karl Marx’s initial theory was not producing the outcomes it foreshadowed, particularly revolutions among developed European countries, became quite apparent for Marxist followers. As seen by the case studies, throughout the 20th century, revolutions had occurred mostly beyond the Industrialized European continent’s periphery. However, rather than forgoing the theory, revolutionary theorists such as Vladimir Lenin emphasized imperialism’s role in capitalist societies’ ability to mitigate Marx’s points of contentions initially thought to create revolutionary situations. For this theory, imperialism meant a state’s ability to expand its geographical control by establishing colonies that could provide further natural resources and additional markets for excess capital (Meyer 1970). Hence, for both case studies, Vietnam and Algeria fell into France’s international monopoly system. That does not mean; however, the newly overexploited population eventually grows tired and revolts. Just as the bourgeois bribes their European states’ populace, so happened with these colonies’ local elites (Meyer 1970 245). For instance, in Algeria, the French emigres reaped colonial exploitation benefits, while in Vietnam, it was the Southern monarchical aristocrats.

In terms of this theory, then, the reason for revolt stems from these regions being weak points of the monopolistic system. Algeria and Vietnam are at the periphery of the “empire” established by the French in this case. Therefore, their governance naturally lacks control and becomes susceptible to revolts, especially when Metropolitan France’s focus becomes occupied with wars dealing with other imperialist states seeking to expand their economic sphere of influence. These wars negatively affect both the winner and loser as their populace become dissatisfied with economic bribery causing domestic tensions to grow (Meyer 1970). For Algeria and Vietnam, World War I and II would be the events to cause the growth of a revolutionary spirit and situation. However, before accepting Lenin’s general theory of revolution, one must look at these wars and whether they are due to economic distribution and competition for spheres of influence. This issue becomes highly contested when analyzing the two world wars as an explanation of nationalism rivals’ economic causes for why the wars happened, meaning Lenin’s theory possibly misrepresents why 20th-century wars occurred.

Conclusion

While not prophetic in pinpointing where the next countrywide revolution would occur, Karl Marx’s theory of revolution provided valuable information in pinpointing which economic stress points within societies scholars should analyze to explain why a revolutionary situation might develop. Marx originally would not have foreshadowed that revolutions would occur in Vietnam and Algeria; rather he would assume these revolutions would occur in industrialized Western European countries. However, his usage of the proletariat-bourgeoisie divides and the Hegelian Dialectic still fit into the revolutionary structures these two countries faced. Ultimately, Marx’s theory continues to inspire revolutionaries and revolutionary scholars. Specifically, decades after Marx’s death, theorists such as Trotsky and Lenin would establish their spin on Marxism. In the second half of the 20th-century academic scholars such as Barrington Moore, Crane Brinton, and Theda Skocpol.

Works Cited

Cole, Joshua. 2010. “Massacres and Their Historians: Recent Histories of State Violence in France and Algeria in the Twentieth Century.” French Politics, Culture & Society 28 (1): 106–26.

Daniel, Jean. 1962. “The Algerian Problem Begins,” July, 1962. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/algeria/1962-07-01/algerian-problem-begins.

Defronzo, James. 1991. “Revolutions and Revolutionary Movements,” New York: Routledge. August 4, 1991https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429494727

Eisenhower, Dwight. “President Dwight D. Eisenhower on the Likelihood That Ho Chi Minh Would Win a National Election in Vietnam in 1955.” n.d. Accessed December 4, 2020. https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/vietnam/55election.htm.

Hitchens, Christopher. 2006. “A Chronology of the Algerian War of Independence.” The Atlantic. November 1, 2006. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/11/a-chronology-of-the-algerian-war-of-independence/305277/.

Hudson, G. F. 2011. “Mao, Marx and Moscow,” October 11, 2011. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/1959-07-01/mao-marx-and-moscow.

Lilley, Kelsey. 2012. “A Policy of Violence: The Case of Algeria.” E-International Relations (blog). September 12, 2012. https://www.e-ir.info/2012/09/12/a-policy-of-violence-the-case-of-algeria/.

Marx, Karl and Fredrick Engels ([1848] 1990), Manifesto of the Communist Party. Beijing: Foreign Language Press.

“Milestones: 1953–1960 – Office of the Historian.” n.d. US Department of State. Accessed December 4, 2020. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/dien-bien-phu.

Sivan, Emanuel. 1979. “Colonialism and Popular Culture in Algeria.” Journal of Contemporary History 14 (1): 21–53.

Vu, Tuong. 2017. “Vietnam’s Misunderstood Revolution.” Wilson Center. June 19, 2017. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/vietnams-misunderstood-revolution.

Wiener, Jonathan M., and Barrington Moore. 1976. “Review of Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World, Barrington Moore, Jr.” History and Theory 15 (2): 146–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/2504823.

Image Attribution

“Karl Marx | Карл Маркс, 1875” by klimbims is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0