4

“We must be very tentative about the prodromal symptoms of revolution. Even retrospectively, diagnosis of the four societies we studied was very difficult, and there is little ground for belief that anyone today has enough knowledge and skill to apply formal methods of diagnosis to a contemporary society and say, in this case revolution will or will not occur shortly. But some uniformities do emerge from a study of the old regimes in England, America, France, and Russia.”

-Crane Brinton (1965, pp.250)

Is revolution something that can be measured or seen before it occurs, or is it due to a set of random events? In his book, ‘The Anatomy of Revolution,’ Crane Brinton breaks down the structure of revolution and explains revolutions’ onsets. This chapter introduces us to the term ‘pre-revolutionary society’ and some of the conditions that may prompt society to head in the direction of revolution. While revolutions do occur under different conditions, people, and geographies, there are still some striking similarities within their societies before the conflict starts. Like Barrington Moore’s work, Crane Brinton helps us conceptualize revolution and pre-revolution. Conceptualizing revolutions in a chronological manner helps us in detecting possible future revolutions and ‘pre-revolution’ societies.

In his 1965 seminal book, ‘The Anatomy of Revolution,’ Crane Brinton conducts a comparative study of the American, English, French, and Russian Revolutions. In his study, Brinton examines the differences and the similarities across these revolutions, bringing his findings into what he calls “The Anatomy of Revolution.” The Anatomy of Revolution would later become a significant revolution theory.

Pre-revolution and Uniformities of Revolution

Crane Brinton compares and extracts similarities between ‘pre-revolution’ Russia, America, Britain, and France. He then compiled these similarities into the general uniformities seen within the revolutions studied. Brinton explains that uniformities support the idea that historical events are not necessarily unique. Instead, uniformities can be systematically identified to predict revolutions. The first of the five uniformities that Brinton identifies is that societies are usually on the ‘up,’ meaning they are economically prospering before revolutions occur. Hence, revolutions do not occur because of ‘starving miserable people’ (Brinton, 1965, pp.250). People that are optimistic and hopeful start revolutions, not when they are hungry, people revolt when they are unhappy. When people hold a government to a certain standard, they expect a certain quality of life threshold. If the government does not satisfy those needs and expectations, they could be in a ‘pre-revolution’ state.

The second uniformity that Brinton identifies is “bitter class antagonism” (Brinton 1965) In societies that tend to have more ‘equal’ classes, more class bitterness exists. The bitterness is typically measured by economic, social, and religious factors. Therefore, the bitterness causes tensions between the ruling class such as the aristocrats and merchant classes and not between the general elites and the downtrodden (pp.251). This is due to the relatively similar ‘wants and needs’ of both classes. However, there is enough of a difference in which tension can grow whether it be because of what God “ordained” or the society’s cultures calls for. These economic, social, and religious restrictions hold down people of all classes. The struggle between classes exposes the “restrictions” or the entry barriers of each class and causes tensions between classes.

The third uniformity that Brinton notes is “the transfer of allegiance of intellectuals” (pp.251). Brinton observes that intellectuals start to side with ‘revolutionary groups’ due to discontent with the way their society operates. The discontent by intellectuals, and their want for change, means that they align themselves against the government.

The fourth uniformity is the ‘inefficiency of governance.’ Government is inefficient, partly through neglect. An example would be the government failing to tax people justly and not organize its finances, thus going bankrupt. The government is also unable to keep up with the speed of change in society and technology/development (pp.251).

Lastly, the fifth uniformity that was observed by Brinton is that the old ruling class come to distrust themselves (pp.252). The old ruling class may lose faith in their class’s old habits and traditions, grow intellectual, become humanitarian, or go over to the opposing side. Overall, these five uniformities are central to Brinton’s theory of revolution, and they make up the anatomy of a revolution. While these uniformities may not necessarily exist in all revolutions, it is interesting to see how they apply to different revolutions. Not all revolutions have the same circumstances, and they all have different ways in which these uniformities are satisfied.

Wider Uniformities

Brinton expands on his central theory of revolution and identifies specific characteristics that affect his theory on revolution. Through his comparison of the four different revolutions mentioned earlier, Brinton identifies a few ways in which revolution is ‘accelerated.’ The existence of a ‘rule of terror’ (pp. 255). A rule of terror is governance by power, punishment, and the quashing of opposition. Brinton observed a rule of terror in the French Revolution where executions were widespread. This ‘rule of terror’ even reaches as far as prying into citizens’ everyday lives, regulating them, and controlling them. ‘Reign of terror’ usually goes hand in hand with ‘strongmen’ governments and religious governments. Brinton explains that this accelerates a revolution by fueling tensions to the point of no return.

Another accelerator identified by Brinton is, which he mentions is not as important as the former, is an industrial revolution. Brinton mentions that industrial revolutions occur at a fast rate, causing increasing development of the printing press, i.e., communication, which allows revolutions to be more streamlined (pp.260).

Adding on to his central theory, Brinton explains some wider uniformities that lead to revolutions. One of which is the ‘promises to the common man.’ Brinton explains that revolutions exhibit a scale of vague promises such as ‘happiness’ and concrete promises such as ‘satisfaction of all material wants, and revenges’ that are made to the common man by the government and never satisfied (pp.262). These ‘broken promises’ lead to discontent, and ultimately revolution. Another note made by Brinton is that there seems to be a development of conscious revolutionary techniques with time. These techniques are what enable, organize, and execute revolutions. As more nations and people revolt, more conscious revolutionary techniques develop.

Stages of Revolution

Brinton also discusses the ‘four stages of revolution.’ which follow the ‘pre-revolutionary states’ countries showed. The first being the rule of the ‘moderates. In the first stage, moderates ascend to power as they look to be the ‘most natural successor’ of the old ruling class. Several factors exist during this stage, including a financial breakdown, where the government cannot manage finances. Another factor is the increase in protests against the government. The protests lead to dramatic events that cause instability. Ultimately, the moderates in power get overthrown by the radicals (p. 253).

The second stage is the rise of radicals to power. Radicals use the revolution to ascend to power and exert a more powerful presence than a moderate government. Radicals do this as they are a small number of well-organized people with high ideals and ambitions. The power lies within a central ‘strongman authority.’ The radical regime imposes its will on people through whatever means are at their disposal (pp. 254).

The radical regime leads to the third stage of the revolution, the crisis period. The reign of terror by radicals in power manifests through assassinations, executions, and quashing of opposition. The radicals establish an authoritarian government that pries into the lives of citizens. A brutal ‘reign of terror,’ combined with inefficient governance of resources and class inequality, blows fire into the flame of revolution. The radically idealistic rule of terror that aims to create perfection through vicious means does not sit well with people. The ‘reign of terror’ causes a ‘Thermidorian reaction’ (pp. 207)

The fourth stage Brinton mentions is the ‘Thermidorian reaction,’ a reaction to the oppressive regime. During the Thermidorian reaction, people overthrow the government and favor a return to moderates in government. Moderates return to power, and the quieter days of before return for the time being (pp. 255). Beyond this stage, Brinton observes that these revolutions had not brought much social change after the four stages occur (pp. 246).

This collection of stages does not end for scholar James H. Meisel. Inspired by the work of Crane Brinton, Meisel adds an addendum to the list. He argues that revolutions do not merely end with the return of a moderate government rather there is a long and drawn-out period that averages around a decade before the next stage starts. This last stage proclaims a subversion of the revolution occurring in which an authoritative actor takes control of the thermidor government (Meisel 1966). At this point one can call a conclusion to the revolution which initially began with the ascension of moderates.

Case Study 1: Russian Revolution

As is mentioned earlier, Crane Brinton’s theory of revolution focuses on the conditions of ‘pre-revolutionary society’ that leads to the formation of revolutionary movements. He breaks these conditions down into five uniformities of revolution. Below there will be a description of them in short as well as the specifics of how these uniformities appear in Russian pre-revolutionary society. This will show the Russian Revolution through Brinton’s eye and provide context. There is an explanation of the stages postulated by Brinton that all revolutions, including the Russian Revolution, went through. Interspersed are some comparisons to Marx only due to the Marxist nature of the revolutionary’s ideals.

Anatomy of a Pre-Revolutionary Society in Russia

The first requirement Brinton finds is that a society must be generally improving, but still provides discontent to their people. Revolutions are inherently optimistic and so the people must have already seen advancement to hope for more. The non-communist, anti-monarchical revolution of 1905 provided this instance. It could be argued that quality of life was improving prior to the removal of the Tsar, as serfdom had been abolished, and generally the Monarchy was being pressured into progressive reform. After the 1905 Revolution Czar Nicholas II promised further reform. However, a decade later events, including WW-I would lead to the 1917 abdication of the Czar (Defronzo 2019). With the removal of the Tsar, former aristocrats, now referred to as the bourgeoisie, began taking power which did not suit the petty bourgeoisie or the proletariat masses (Brinton, 1965, pp. 250).

This brings us to the second of Brinton’s uniformities: Class Antagonisms. A theorist like Karl Marx would argue that Class Antagonisms are constantly present, regardless of revolutionary likelihood, and would cite these antagonisms as the most important cause of revolution. Depending on how you look at it, it certainly could be what Marx claims. The antagonisms present when the Revolution began were many. There were pre-existing conditions between members of the petty bourgeoisie who made up the intelligentsia and the established former aristocrats. Here the tension was strong due to the dynastic nature of aristocratic wealth as opposed to the intelligentsia who despite still having wealth, felt apart from the rest of the bourgeoisie for their self-stylized commitment to the proletariat. The proletariat in turn was growing as serfs became free and sought to better their lives through factory work in cities. These factories served as the breeding ground for radicalization of workers against factory owners and other members of the wealthy elite (pp. 251).

As mentioned above, the move by the intelligentsia led by Lenin fulfills both Brinton’s third uniformity of “the transfer of the allegiance of the intellectuals” (pp. 251), as well as the fifth uniformity of division amongst the ruling class. The Marxist intelligentsia of pre-revolutionary Russia felt incensed by the notions of Communism to support the proletariat they saw struggling to survive in the newly enlarged industrial sector. This division brought a split between the old bourgeoisie and the new. The new siding with revolutionaries and bringing with them greater power to the revolution as a whole. Brinton wrote in his fourth uniformity that, “the governmental machinery is clearly efficient” (pp. 251). He elaborates that this is not just in terms of economic management, but also in the use of its military and paramilitary (pp. 252). In Russia prior to the revolution, the Tsar’s use of the military was historically oppressive. The failures of the Russian military during World War I also greatly contributed to the distrust and discontent of civilians towards the military apparatus and the disillusionment of members of the military toward their leaders and even towards the Tsar himself.

Stages of The Russian Revolution

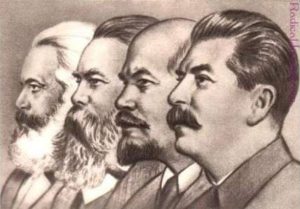

Crane Brinton states that the first to seize control of a revolution are the moderates, and although they are separate from the regime of old, they are still much less radical than those to come and their loss of power tends to be due to their own limits. In Russia, as Brinton writes, “They are not always in a numerical majority at this stage – indeed it is pretty clear if you limit the moderates to the Kadets they were not in a majority in Russia in February 1917” (pp. 253). The rise of the radicals follows this, and you see the Revolutionary direction veer to the left. In Russia this came in the form of the November revolution where the much more radical Bolsheviks and Mensheviks seized power aggressively and violently under the guise of proletarian emancipation. Brinton’s “lunatic fringes” (pp. 254), here, were total anarchists and those who wanted the dissolution of the entire and any state apparatus. The third stage of the revolution occurred as the strongman Lenin seized power as the leadership of the Bolsheviks. The takeover resulted in the brutal dissolvement broadly against anyone Lenin considered counter-revolutionary, involving banishment or later, executions. With the revolutionary movement consolidated under one revolutionary party, and one revolutionary leader, the fourth stage of Thermidor occurred. Albeit the civil war continued for four more years eventually the Soviet Union was formed under Lenin’s leadership. Lenin reestablished the state, enforced strict anti-revolutionary policy against reactionaries, and cemented the regime as the new “true” state of the Soviet Union. However, taking into account James Meisel’s Addendum the last stage of the revolution can be said to occur with the consolidation of Joseph Stalin’s control over the Soviet Union. As an authoritative figure Stalin reverted the revolution and set the Soviet Union’s course toward a totalitarian regime that would last for decades after Lenin’s death. Therefore, the revolution did not end with Lenin’s unification of the Soviets but with Stalin reactionary reformation of the Soviet Union.

Case Study 2: French Revolution

Alongside with the Russian Revolution, The French Revolution was analyzed in Brinton’s “Anatomy of a Revolution”, allowing us to draw certain comparisons and contrasts between the French Revolution and Crane’s breakdown of revolutions. Crane breaks revolutions down into 5 basic uniformities of the revolution, which we broke down earlier.

Anatomy of the French Revolution’s Uniformities

Starting with the first uniformity, societies are usually prospering economically before revolutions. Leading up to the French Revolution, France was doing quite well financially, but assisting the future United States with their revolution as well as the 7 Years War with England began to drain their treasury (McPhee 2002). Alongside this, they had a horrible tax system, which began to really widen the class gap between the rich and the poor once the new King Louis XIV began to tear through livres like candy. And seeing as the clergy and nobles were mostly exempt from taxes, this unfortunately placed the tab on the lower class, who began to grow tired of picking up the check for the bourgeoisie year after year (McPhee 2002).

Bitter class antagonism also plays a role. France had long established beef between the estates, which came to a head during the Tennis Court Oaths, when the third estate met at an impromptu courthouse on a tennis court to lay their grievances and establish what they wanted. Aside from this, the class tensions were always at a high with the third estate, seeing as most of the clergy and nobles did not have to pay any taxes so the poor were having to pay far more than their fair share of taxes (McPhee 2002). This flaw in their tax system is one of the things that widened the gap between the upper and lower classes to a point of no return.

At the time, many modern French thinkers were aligned with the side of the revolutionaries, such as star lawyer and statesman, Maximilian Robespierre. Robespierre, along with help from others, started the Jacobin party, a group oriented around ending the monarchy and King Louis the 16th’s regime. The Jacobins had formed long before the heads went flying, and in their early days advocated for mass education, women’s suffrage, and the separation of church and state. This transfer of sides and mass push of intellectuals were able to inspire the masses so well that they succeeded in their goal of killing King Louis and semi-successfully ending the monarchy.

One of the staples of elementary school history classes is the phrase “let them eat cake”, and while this phrase was never actually said (it was more along the lines of let them eat brioche), it highlighted the idea that leading up to the French Revolution, the nobles of France did not really care for anything but themselves and their lavish lifestyles. They had a wide disconnect from the famished and frustrated peasant class that was paying for their lavish lifestyles. In a feeble-minded attempt to make up for the fact that he had spent essentially all the livres in the French National Treasury, King Louis XIV ordered a new currency be printed and donated to the hungry masses of Paris. Noticing that the people of Paris had quite literally no money, the crown printed way more of this currency, assignat (McPhee 2002). By the end of the year, they had been introduced to the economy, the money French people were using was worth next to nothing, the spending power going down 99% (Ebeling 2007). Hence, these actions are all instances of inefficient government uniformity.

The last non-chronological uniformity is the growth of distrust between the ruling elite. One strong example of this occurring the French Revolution comes in the form King Louie re-shuffling his cabinet. As the revolution began to build, King Louis felt the pressure rising, and began to shed some previously well-liked members of his circle, such as Jacques Necker, his only non-noble in the cabinet. Necker’s replacement would be replaced by Joseph Foullon who would be beheaded by peasants (McPhee 2002).

The French Revolution can easily be explained by Crane Brinton’s theory of the Five Stages of Revolution. In the preliminary stage, the Old order, France was economically weak due to the state being in debt from assisting in the American Revolution. Class antagonism was similarly there as well as a government that was unable to enforce their rules. These concerns were seen in the formation of the National Assembly. The first stage, moderate regime, typically has large protests that the government cannot suppress, this was seen in the peasant uprising against the first and second estates. A characteristic of the second stage of a revolution is moderates gaining power. The moderates gained power in France by accepting taxes and giving up their more upper-class benefits. This led to a fairer government; however, this government was certainly still not completely fair. The third stage of the revolution, radical regime, is when the radicals took over and there were roots to radicals all over France. Radical Maximillian Robespierre gained power through a coup d’état terrorized the rich by killing over 40,000 people in a single year often by guillotine. The fourth stage, Thermidorian reaction, occurred between the execution of Robespierre and Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup. The death of Robespierre ended the reign of terror period and Napoleon’s ascension as the leader of France brough national order. He created a national bank and mandated taxes for all while promoting equality which caused an uptick in pride in French citizens. The French Revolution stages, however, do not end with Napoleon’s rise in power. Based on James Meisel’s addendum to the stages. After consecutive years of war lead Napoleon to become the authoritative figure that reverts the revolution and establishes an empire, now known as the First French Empire (Brinton 1965). Overall, Brinton’s theory of the Four Stages of Revolution provides a groundwork for how a revolution can fail and this can be seen through the lens of the French Revolution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while these revolutions have definite differences, they still share simple uniformities that allow the revolution’s conceptualization. Crane Brinton compiles these uniformities into what he calls ‘The Anatomy of Revolution.’ Brinton explains the necessity of studying men’s deeds and men’s words as there is not always a logical and straightforward connection between the two. Men sometimes say something yet have differing actions from what they said. Humans have dispositions that cannot be rapidly changed by ‘extremists/revolutionists.’ The enforcement of rapid change through any means may have the opposite result. A ‘scientific way’ of identifying when and where a revolution may occur can lead to peaceful alternatives that minimize damages, bring positive change, and shed light on citizens’ struggles and discontent.

Works Cited

Armstrong, Stephen, and Marian Desrosiers. “Helping Students Analyze Revolutions.” Social Education, National Council for the Social Studies, 2012, pp. 38–46.

Brinton, C. (1965). The anatomy of revolution. New York: Vintage Books.

DeFronzo, James. 2019. “The Russian Revolutions and Eastern Europe.” In Revolutions and Revolutionary Movements, 39-87. New York: Routledge.

Ebeling, R. (2007, July 01). The great French Inflation: Richard m. Ebeling. from https://fee.org/articles/the-great-french-inflation/

McPhee, Peter. 2002. “The French Revolution 1789-1799”. Oxford University Press.

Strayer, Robert W. Ways of the World: A Brief Global History with Sources; Volume 2: since the Fifteenth Century. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2019.

Strether, Lambert. “Crane Brinton on Revolution.” Naked Capitalism, 7 Sept. 2015, www.nakedcapitalism.com/2015/09/crane-brinton-on-revolution.html.

Image Attribution

MARX, ENGELS, LENIN Y STALIN by Carlos XVIG is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0