3 Analyzing Research & Writing the Literature Review

Chapter Overview

At this stage of the process, you have been with your agency for a few weeks, gotten more familiar with the work that they do, and established a social issue on which to center your project proposal. Knowing and naming the social issue is a critical step to developing a literature review.

A literature review is a written product in which you will develop and demonstrate a working knowledge of your topic through deep reading and analysis of existing research. During this process, you will proceed through the steps of (1) identifying guiding questions & key words, (2) conducting a targeted search, (3) reviewing & selecting literature, (4) analyzing that research, and (5) organizing & constructing the review. Ultimately, a literature review will culminate in justification for your project proposal. Later, as you implement your project, the research you’ve reviewed will inform both the content and methodology you use.

Before we dig into how to complete a literature review, we’d like to discuss the value of writing as a social work skill and provide a refresher on the types of published research. These topics should help prepare you for the critical analysis & drafting process that you are about to undertake. Later in this chapter we will provide guidance on how to approach writing your literature review, including advice on structure and organization of your ideas.

Writing as a Social Work Skill

Learners often note that the literature review is the most challenging part of developing the Capstone project. Yet, it is possible to reframe this challenge by discovering the meaning of writing as a key skill. Social workers write all the time for multiple purposes. You’ve likely heard the phrase, “If it isn’t documented, it didn’t happen,” meaning good documentation is critical to ethical and effective service. In addition to case notes and process records, we also write grants for funding, create marketing materials, deal in email communication, and contribute to knowledge development and creation. Writing is a fundamental part of so much that we do as practitioners.

“Writing is an affective experience that can negatively affect cognitive processes” (Miller et al., 2018). In other words, how you feel about writing impacts your ability to write. Addressing these feelings is an important first step as you begin your literature review. Here are a few strategies that might be helpful to your process:

- Completing a Writing Strengths and Barriers Assessment

- Completing a Contemplative Journal Exercise – This article offers guidance on how to approach writing with care, reflectiveness, and intentionality.

- Use the 5 Why’s, get at the root of your barriers & fears – Described in the previous chapter, this exercise can help you understand your motivations, barriers, and fears about writing.

Now that you’ve taken some time to intentionally reflect on your writing practice, you’re ready to reconnect with your foundational learning about the nature of knowledge and research.

Published Research & Information

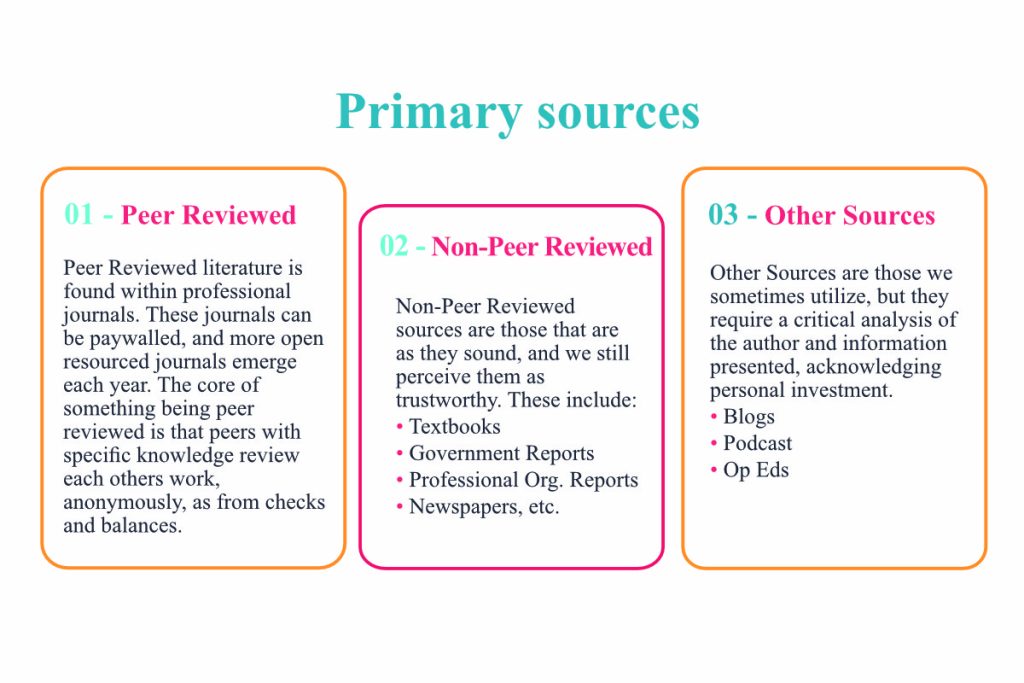

Primary Sources of Data

This section will describe the different ways in which data and knowledge is provided to us. We can engage knowledge and expand our understanding through three primary means: (1) peer reviewed journals, (2) non-peer reviewed sources, and (3) other information. Within each of these different categories are multiple venues for knowledge sharing. As you’re reviewing these primary sources of information always be sure to critically consider who is writing it, saying it, offering it, and what trust do we have in their story, their evidence. What is their positionality, who are they in the world, and how does that inform our comfort with the information they have shared?

Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

Peer-reviewed journals are considered our most trustworthy form of research-based data and knowledge. During peer review, two or more experts with knowledge of the social issue being studied or research methods being used evaluate the quality of the study; they review the study manuscript for issue development, methodological considerations, and strong theoretical arguments. Only after an iterative process of revisions will the study be published for a broader audience. Most evidence presented in your paper should incorporate peer reviewed literature.

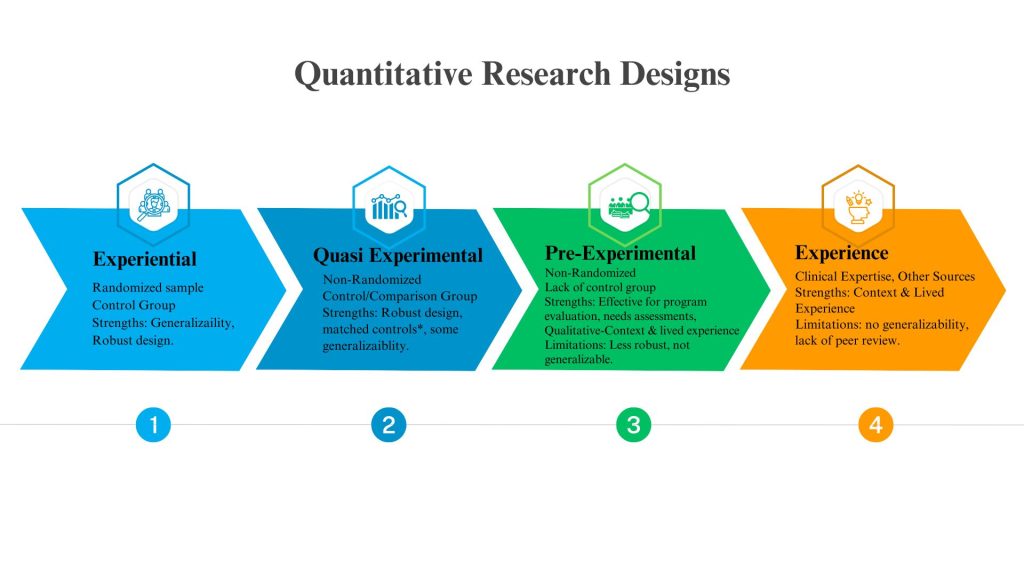

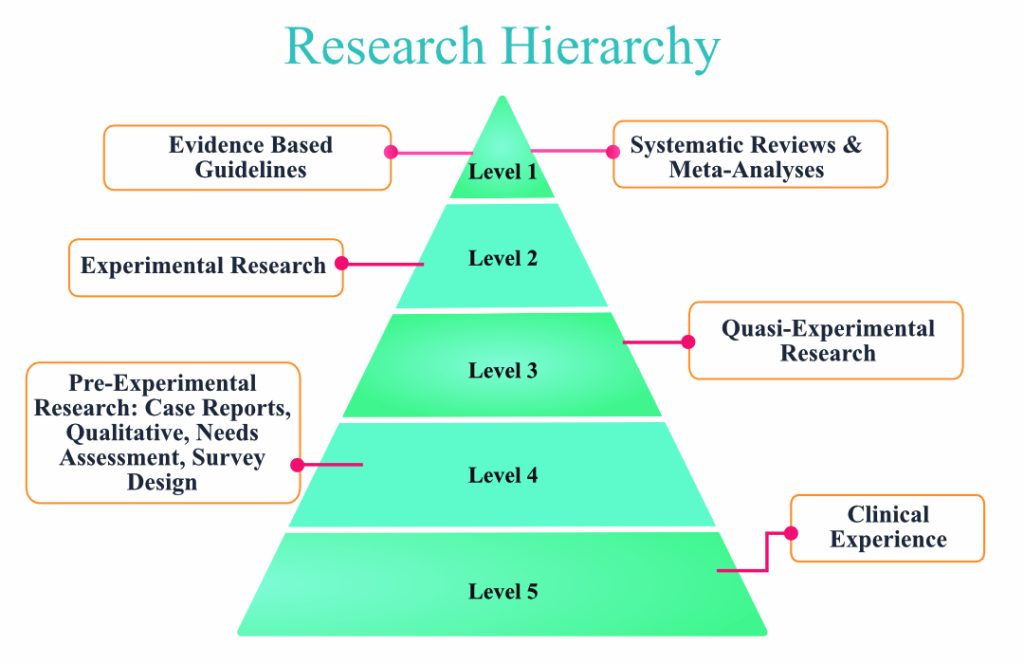

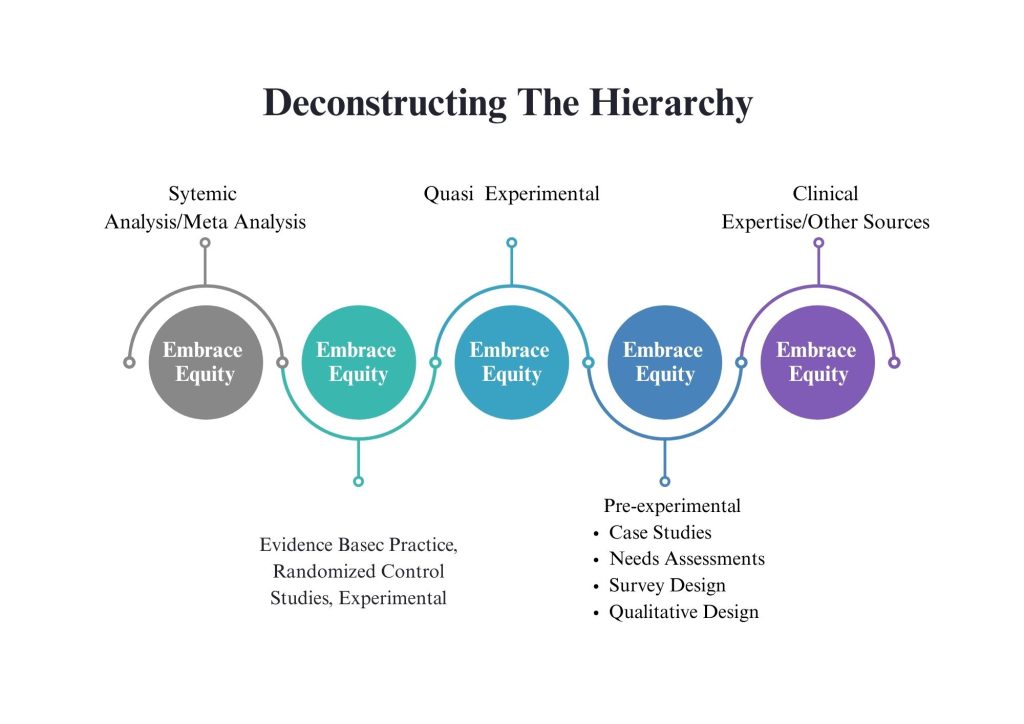

There are five primary types of articles that fall under peer reviewed literature: Reviews (i.e., Meta-analysis or Systematic Review), Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, or Theoretical. Peer reviewed articles are arranged into a hierarchy; those studies which have more robust research designs, increase our faith in the findings and are more generalizable fall into level 1; articles with more limited designs follow into lower levels on the hierarchy (see diagram below). In the pages that follow, we will briefly define each of these article types.

Reviews

Reviews include meta-analysis or systematic reviews and are at level 1 in the hierarchy. Reviews are a great place to begin developing your literature portfolio (more on this later), as they combine raw data from multiple studies and analyze the pooled data using tested methods. They often bring together at least a decade’s worth of knowledge about a certain issue, use tried and proven methods for collecting and analyzing the data, and present interpretations.

There are several frameworks for completing a scoping literature review, as identified here. The most common methodology you will encounter is the PRISM method. This has been shown to be the gold standard in meta-analysis across the field and identifies for the reader the strength of evidence before them. Sampling within the review will look different than how we commonly think of sampling (as you’ll see below), in that analyzing the sampling plan of a review is not about the human participants, but the journal articles (studies) chosen for analysis. The key to remember related to review sampling is to think critically regarding the total number of studies identified, then the total number of studies included, contextualized through the sampling frame (e.g., criteria for study inclusion). For example, if the authors state that they identified 200 articles but only included three, I would view the findings with more skepticism than if they had included 60 studies.

Finally, in a review, data collection methods are determined by the measures used in the included studies. Authors should clearly indicate whether these studies employed reliable and valid measures. It is common for some studies to meet these standards while others do not, so pay close attention to the authors’ justifications to help clarify potential limitations. Overall, reviews offer a broad understanding of theory and strengthen the ability to generalize findings to wider populations.

Quantitative

Quantitative Articles (Levels 2–4)

Quantitative research is objective in nature, relying on the systematic collection of empirical, numerical data. Through measurement and statistical analysis, it tests hypotheses about general laws that apply to human behavior. In the hierarchy of evidence, quantitative studies typically fall within Levels 2–4 (comparison chart [PDF]). Most often, they are outcome evaluations—studies assessing the effectiveness of an intervention for specific populations on a targeted change variable (e.g., depression, anxiety, grief).

Level 2: Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) & Experimental Designs

Level 2 studies use rigorous designs that provide strong evidence for practice.

-

Evidence-Based Practices (EBPs) are modeled after the medical field, often using randomized controlled trials. According to Drisko & Grady (2015), EBPs integrate four equally weighted components:

-

Current client needs and situation

-

The most relevant research evidence

-

Client values and preferences

-

Clinician expertise

-

These studies typically include multiple populations in multiple settings and aim to prove an intervention’s effectiveness for certification by entities such as the Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (EBP resource search).

-

Experimental Designs share similarities with EBPs but may not be double-blind. In these studies, researchers know which participants are receiving the intervention and which are not (placebo). The primary goal is to determine whether a causal relationship exists between variables. Key elements include:

-

At least two conditions (intervention and control group)

-

Random assignment, meaning each participant has an equal chance of being placed in any condition

-

Level 3: Quasi-Experimental Designs

Quasi-experimental studies also include at least two conditions but do not involve random assignment. Control groups are used, but participants are placed into groups through non-random means.

Common in social work and other social sciences, these designs often avoid randomization for ethical reasons—such as not denying services to individuals in need. While waitlist controls can be used, the ethical priority is to maintain fairness, such as “first come, first served” practices.

Level 4: Pre-Experimental Designs

Pre-experimental studies are widely used in the Evaluation Capstone option and include designs such as:

-

Case studies

-

Needs assessments

-

Correlational studies

-

Customer satisfaction surveys

-

Qualitative studies (also Level 4; see qualitative section below)

These studies do not use randomization or control groups, though comparison groups may be present. One-group pre–post outcome evaluations are common but have limited external validity. Demographic comparisons (e.g., by socioeconomic status, gender, race) may be included, providing insight into the study population but not generalizable to other communities.

Level 5: Theoretical and Anecdotal Sources

At the lowest level of the hierarchy, Level 5 includes theoretical articles, anecdotal evidence, and other sources that offer valuable insights but lack empirical testing

Qualitative

The primary difference to keep in mind between quantitative versus qualitative, is numbers versus language, respectively. Qualitative studies examine words or other media to understand their meaning by focusing on the lived experiences of specifically identified groups of individuals and include an analysis of language. Similar elements of research design are also employed within the qualitative space, it is the unit of analysis that separates them. However, due to the nature of seeking specific individuals with specific lived experiences, the ability to randomize qualitative studies is not commonly possible. In addition, the hope is not to compare experiences, but to assess and interpret experience with the hope of identifying shared themes, while also attending to possible outlying stories.

Mixed Methods

Mixed Methods studies have never made an appearance on the hierarchy as it’s own type of study. The key with mixed methods studies is that the researcher must have a plan to analyze both the quantitative and qualitative designs. In addition, the reader needs to have a good understanding of how the researcher combined the different strands of data and how they informed one another. The three most common ways that mixed methods are implemented include: Quantitative before Qualitative, Qualitative before Quantitative, or simultaneously. While mixed methods studies do not show up within the hierarchy as a unique design, it is critical to use our knowledge of the strengths and limitations of both quantitative and qualitative data to analyze reliability and validity.

Theoretical

Theoretical articles are exactly what they sound like—articles that present or elaborate on a theory. They function much like an extensive literature review, drawing on multiple sources to weave together a cohesive theoretical premise. The main way to distinguish a theoretical article from a research study is by looking for a methodology section. Because no original research has been conducted, theoretical articles do not include one. As a result, they are not evaluated in the traditional way that examines the strengths and limitations of a research methodology.

Identifying Relevant Research

Okay, now that you have a sense of the types of sources you will be reviewing to help you develop your literature review, it’s time to start developing a portfolio of resources. The library, search engines, and AI systems like Research Rabbit are important tools in this process. One way to begin is to develop a list of key words based on the issue you want to explore. While this list may be the simplest way to guide your search, it may also result in an overwhelming number of studies. If you are overwhelmed by the amount of information, you can limit the returns by using key words such as, peer reviewed journals or meta-analysis, identify a specific geographic location, or setting time boundaries (i.e. 2015 – present). At times, I will also put a limit on the number of articles that get me started. Such that, I set a boundary of pulling no more than 7 articles as a starting point, and once I’ve hit that limit, I stop my search and begin a review of what I’ve pulled.

The second method of identifying relevant research is through the development of guiding questions. Guiding questions are those questions you want to ask of our knowledge base. Why does the issue exist? What interventions are most effective for addressing this issue? Who is most impacted by the issue? Guiding questions may help to bound your search more than keywords, thereby streamlining your process. You may consider using the 5 Why’s method described earlier, particularly if you’d like to do a deeper dive into the root causes of your chosen issue. Both keywords and guiding questions can be used through your university library and most search engines.

Finally, consider the use of AI in beginning your search. You can put a guiding question into ChatGPT or a similar app and receive an overview with a list of references to get you started. Systems like Research Rabbit allow you to ask a guiding question or upload an article you’ve located, and it will draw you a concept map that demonstrates the connections between your identified article and other similar articles. This tool will provide information on how often the article has been cited, which connections are most significant, and those that appear to be the most significant to your understanding. While this guidebook will not provide full directions on utilizing AI systems, you can find additional information and resources in this AI Statement and Resources document.

The Theory Based Literature Review

To write a comprehensive literature review, you will need a diverse body of knowledge to work from. The two key elements of your literature review that come from our knowledge are the theory of the problem/issue and the theory of change. This should be your clue that you are writing a theoretical literature review. A theory is “a systematic set of interrelated statements intended to explain some aspect of social life” (Rubin & Babbie, 2017, p. 615). A theory allows us to explain and answer the why questions. Why are these two things connected? Why is there a relationship between these experiences? Theory is the answer to most why questions. For example, it’s widely believed that a healthy breakfast for children is important for their engagement in education and ability to learn. Great, but why do we believe this? Because researchers have found that food is fuel, it gives us the energy and calories we need to engage with the world. Remember that when talking theory, it’s not important that you introduce a popular theory that books are written about (e.g., attachment, strengths based, trauma), we have no name for the theory presented above. Therefore, what is important is that you describe why we believe something is reliable, valid, and/or trustworthy, and not just that it is. When writing your literature review, think about telling a story. A story that has a central idea with a beginning (theory of the problem), middle (the theory of change), and end (new, revised, or confirmed theory).

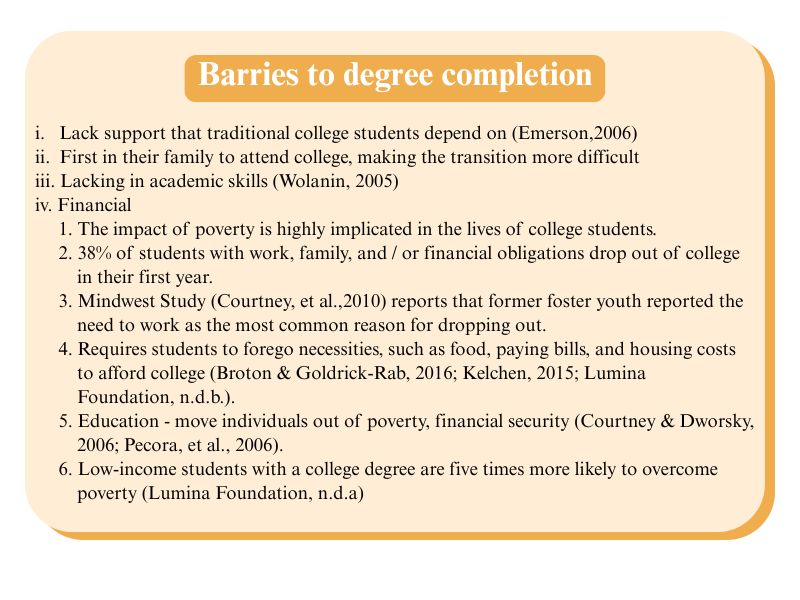

Theory of the phenomenon

As you begin developing your paper, it is essential to explain why the social issue you are exploring exists and how it impacts individuals and communities at the micro, mezzo, and macro levels. Start by identifying the risk and/or protective factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of experiencing the issue. Then, describe the consequences—what happens as a result of experiencing it.

For example, if your focus is anxiety, the literature might point to trauma, isolation, poverty, or chronic stress as common precursors. Because there is often a long list of potential risk factors, your paper should focus on just three or four. You can acknowledge this limitation by stating, “While there are numerous risk factors, this paper will focus on A, B, and C.” Protective factors are often the inverse of risk factors, so it’s best to choose one direction to avoid repetition.

Remember, this is a theoretical paper—your task is to explain why we understand, for example, that isolation can lead to anxiety. Next, outline the key consequences of the social issue. In the case of anxiety, these might include depression, isolation, substance use, or suicidality. Again, narrow your focus to three or four primary consequences. If you’re unsure which to prioritize, consider your population of interest: “What do clients at my agency most often present with?”

Keep the sequence clear: risks precede the social issue; consequences follow it. Staying focused on the factors most relevant to your field placement will help keep your paper grounded. Finally, recognize that some experiences may function as both a risk and a consequence. For instance, isolation might cause anxiety for one person, but for another, anxiety might lead to isolation. This is where theory becomes critical—it provides the framework and language to explain why certain experiences can occur both before and after the onset of a social issue.

Theory of change

Once you have established the theory of the phenomenon, the next step is to explore what interventions exist to address the social issue. This is where you can apply a theory of change from either a preventative or intervention perspective:

-

Preventative approaches target risk factors to stop the social issue from developing.

-

Intervention approaches are implemented after the issue exists, aiming to prevent or reduce its consequences.

When discussing the theory of change, address three core questions:

-

What is the intervention, and what does it target? (Provide a brief overview.)

-

Is the intervention effective?

-

Why or why not? (Explain using theory.)

Using theory means explaining why an intervention is or isn’t effective and outlining its pathway for change. For example, if you choose Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) as an intervention for anxiety, the theory suggests that by helping individuals recognize how thoughts lead to feelings and behaviors, they can interrupt and change behavior patterns. Keep the explanation simple—state why we believe it works.

You are encouraged to explore at least three different interventions. A practical starting point is your field placement: identify which theories or interventions are already being used to address the issue and build from there.

Evidence matters. One study alone is not enough to establish credibility. If you are reviewing CBT, include at least three peer-reviewed articles examining its effectiveness. This principle applies across your literature review—both your theory of the problem and your theory of change should be supported by multiple studies. Research depends on replicability, and so should your analysis. As a general rule, aim for at least three sources to support each major idea.

Theory Development worksheet [fillable PDF]

Critical Analysis of Literature

An important element of being a good consumer of research is to understand the strengths and limitations that are always present, even within the most structured and bounded project. In addition, the NASW Code of Ethics calls on social workers to stay current and up to date on emerging knowledge, as a means of honoring the value of competence. As researchers and evaluators, we acknowledge that there are always limits to our knowledge and understanding. While we strive to put enough guardrails and protections into place to create a solid understanding; those understandings must be contextualized through the design strengths and limitations. The scientific method is at the core of the analytic process. Below you will read about the classical method of analysis based on a hierarchical model of design, or classic model of analysis. However, as we continue to expand our understanding of the human experience, it is also important that we analyze knowledge from a cultural standpoint as a means of deconstructing the role of white supremacy with research & evaluation, as well as all knowledge construction. Therefore, as a starting point for your learning, a model of multicultural validity is also presented.

Classic analysis, hierarchical model

Internal & External Validity

Our goal in reviewing the literature is to present a synthesized, critical analysis of the existing knowledge base. This means not only summarizing what is known, but also evaluating the strengths and limitations of the research as well as any gaps in our understanding. A literature analysis is an essential step in developing as a critical thinker, it demonstrates your ability to assess the quality of evidence and decide how confidently the findings and theories can be used to inform your project.

By learning to evaluate research design, sampling methods, and data collection measures, you strengthen your ability to be a responsible consumer of research and media. This skill not only supports the development of your current project but also contributes to your long-term professional growth.

In this guidebook, we will focus specifically on how to assess a study’s validity by analyzing its design, sampling strategy, and measurement tools (for a more in-depth discussion of these topics, see DeCarlo et al., 2021). At the core of analyzing strengths and limitations is to consider its internal and external validity.

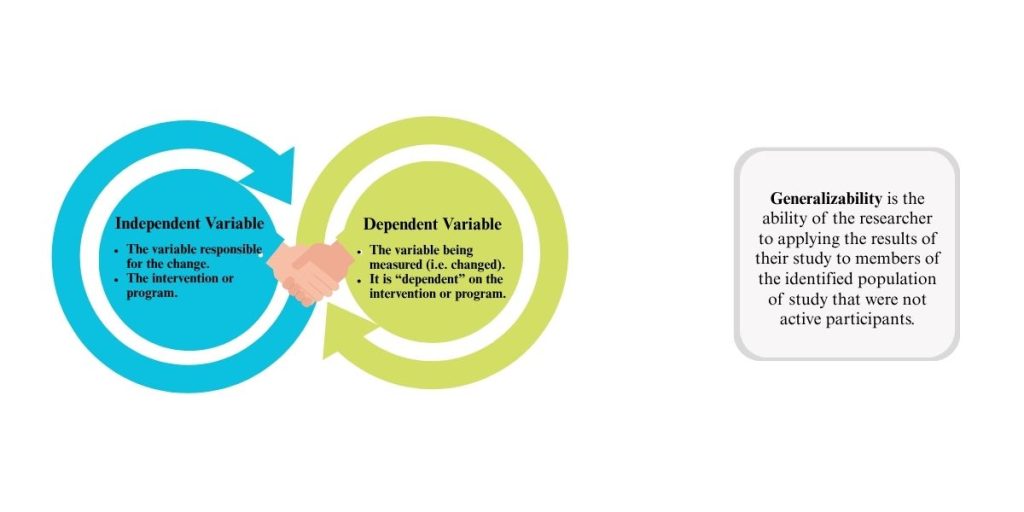

Internal validity refers to the degree to which a study can confidently demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship between variables. It examines whether changes in the dependent variable (the outcome being measured) can be attributed solely to the independent variable (the intervention or factor being manipulated) rather than to other influences. High internal validity means the study has effectively controlled for confounding variables, biases, or alternative explanations, ensuring that the observed effects are the result of the intervention itself.

Core aspects include:

-

Causality: Demonstrating that the independent variable directly influences the dependent variable.

-

Control of variables: Reducing the influence of confounders or external factors.

-

Accuracy of conclusions: Ensuring observed effects are not due to chance, bias, or methodological flaws

External validity refers to how well research findings can be applied beyond the specific sample or conditions of a study. It addresses whether the conclusions drawn are relevant for different people, settings, or points in time, rather than being limited to the original participants or environment. Studies with strong external validity generate insights that are meaningful and applicable in broader, real-world contexts.

Core aspects include:

-

Generalization: Applying results to larger or different populations.

-

Real-world relevance: Ensuring the findings have practical use outside the study.

-

Transferability: Allowing results to be replicated across various situations or contexts.

While each of these aspects have a role, randomization is one of most rigorous tools for establishing the validity of a study. Randomization is the process of assigning participants to different groups (e.g., intervention and control) purely by chance, giving each participant an equal opportunity to be placed in any group.

Why it’s important:

- Reduces Selection Bias – Ensures that groups are similar at the start of the study, making it more likely that differences in outcomes are due to the intervention rather than pre-existing differences.

- Improves Internal Validity – Strengthens the ability to make cause-and-effect conclusions by controlling for confounding variables.

- Supports External Validity – Increases confidence that the results can be applied to other populations, as the sample is more likely to be representative.

- Enhances Credibility – Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered one of the highest levels of evidence in research because they combine rigorous control with unbiased group assignment.

In short, randomization helps ensure that your study’s findings are both trustworthy and applicable beyond the specific sample studied.

Assessing Validity in a Journal Article

When you read a journal article, part of your job is to determine whether the study’s findings are credible and whether they can be applied to broader contexts. This involves looking at both external validity (generalizability) and internal validity (causality and accuracy).

Assessing External Validity – Can the results be generalized?

External validity is closely tied to sampling, how participants were selected and whether the sample reflects the larger population. A study’s generalizability is stronger when the sample is randomized and systematically drawn from a well-defined sampling frame.

Example:

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study (Felitti et al., 1998) surveyed over 10,000 Kaiser Permanente members using a structured process and a clearly defined, relatively representative sample. This large sample size, standardized data collection, and consistent analysis allowed researchers to link childhood trauma with a wide range of health outcomes. Despite some limits (such as being drawn from an insured population), the methods and scale give us confidence that the findings apply broadly to the U.S. population.

Why methods matter:

If, instead of using a structured and systematic sampling process, the researchers had relied solely on sending out surveys to all patients and analyzing only self-selected responses, the study’s validity would have been significantly compromised. A self-selection approach introduces sampling bias, as those who choose to respond may differ in important ways from those who do not, potentially overrepresenting individuals with certain experiences or characteristics while excluding others. Without randomization or a controlled sampling frame, we lose confidence that the results accurately represent the population of interest, making it difficult to apply the findings beyond the respondents themselves. This would substantially reduce the reliability, validity, and generalizability of the conclusions drawn.

When reviewing a study:

-

Ask: Was the sample random or representative?

-

Check: How were participants recruited?

-

Consider: Could certain groups be over- or under-represented?

Assessing Internal Validity – Can the results be trusted as cause-and-effect?

Internal validity focuses on whether the independent variable (what’s being manipulated—e.g., an intervention) is truly responsible for changes in the dependent variable (what’s being measured—e.g., outcomes). Two key areas to examine are:

Data Collection Measures

Reliable and valid measures are essential.

-

Reliability means the measure consistently produces the same results across populations and over time.

-

Example: If a client takes the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) today and again in six weeks with similar results (assuming their symptoms haven’t changed), the tool is reliable.

-

-

Validity means the tool measures what it’s intended to measure.

-

Example: The BDI accurately measures depression symptoms, not anxiety or unrelated constructs.

-

When reviewing a study:

-

Ask: Were the measures tested for reliability and validity?

-

Check: Have they been used successfully across different communities and cultures?

Research Design, Control Groups, & Evidence Hierarchy

A study’s design affects how confident we can be in its findings. The hierarchy of evidence ranks study types by their strength in supporting valid conclusions.

The role of control and comparison groups:

-

Control groups consist of participants who do not receive the intervention. They provide a baseline to compare changes in the intervention group, helping ensure that differences in outcomes are due to the independent variable and not other factors.

-

Comparison groups may receive an alternative intervention or a different “dose” of the same intervention. While they can be useful, they are generally less rigorous than randomized control groups because differences between groups may be due to pre-existing characteristics.

-

The strongest designs randomly assign participants to groups. This reduces selection bias and increases confidence that the groups are equivalent at the start of the study.

Example:

In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a new social work intervention for reducing youth homelessness, random assignment ensures both groups start with similar characteristics. If only the intervention group shows improvement, we can be more confident the intervention caused the change. If instead researchers assigned groups based on availability or willingness to participate, differences in outcomes could reflect pre-existing group differences rather than the intervention itself.

When reviewing a study:

-

Identify whether there was a control or comparison group.

-

Ask: Were participants randomly assigned to groups?

-

Consider: Without a control group, could other factors explain the results?

Bottom line for students:

When you evaluate a study’s validity, look at who was studied, how they were selected, whether there were control/comparison groups, what was measured, and how the study was designed. Strong validity, both internal and external, means the findings are trustworthy and useful in real-world contexts. Weak validity means you should be intentional and critical when drawing conclusions or applying the results.

A Note of Caution: While the research hierarchy can be useful as a heuristic device, it is also problematic in how it values one form of knowledge over others. That is, such hierarchies fail to adequately attend to equity, intersectional identity, and the benefits of a postmodern perspective which values lived experience. We maintain that while all knowledge is not equal, all knowledge can be considered equally within the context of the strengths and limitations of the design. We invite you to think about the hierarchy of evidence, not as a privileged framework, but as a function of the design elements that provide more structure around research methodology, interpretation, and generalizability. The graphic below offers an alternative visualization, and later in this chapter we’ll reference the Multicultural Validity approach to contemporary analysis.

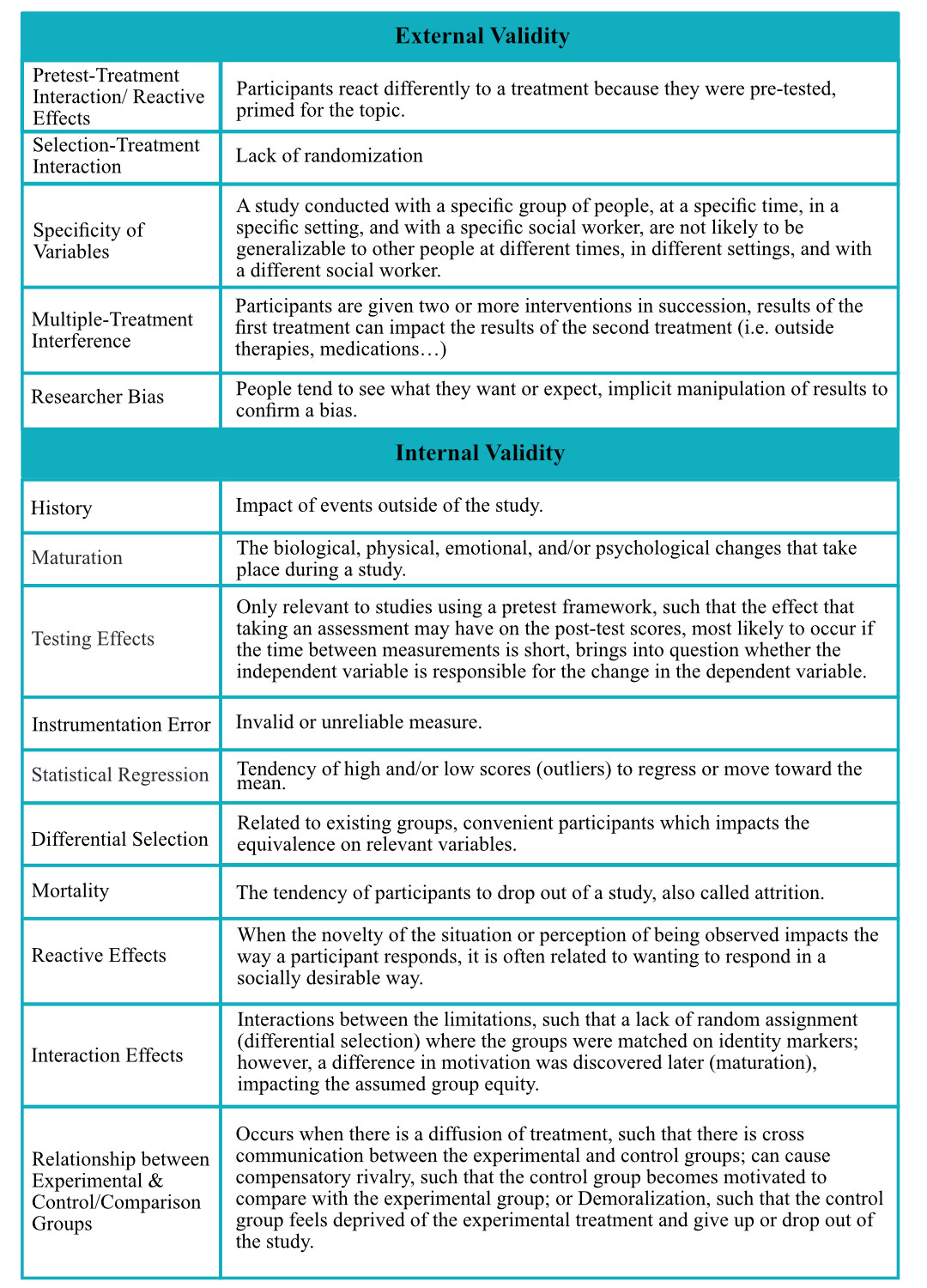

The table below identifies common threats to the internal & external validity of research studies. We encourage you to reference this table as you assess the potential strengths & limitations of the literature you are reviewing.

The table below identifies common threats to the internal & external validity of research studies. We encourage you to reference this table as you assess the potential strengths & limitations of the literature you are reviewing.

| Type of Validity | Threat | Definition |

| Internal | History | Events outside the study that occur between measurements and affect the outcome. |

| Internal | Maturation | Changes within participants over time that could influence results (e.g., aging, fatigue). |

| Internal | Testing | The effect of taking a test more than once, which may influence participants’ scores. |

| Internal | Instrumentation / Measurement Bias | Changes in measurement tools or procedures that affect comparability of results. |

| Internal | Selection Bias | Differences in characteristics between groups that exist before the intervention. |

| Internal | Attrition | Loss of participants from the study, which may alter group comparability. |

| Internal | Regression to the mean | When extreme scores naturally move closer to the average over time. |

| Internal | Confounding Variables | Uncontrolled variables that influence the dependent variable. |

| External | Population Validity/Randomization | Extent to which study results can be generalized to other groups or populations. |

| External | Ecological Validity | Extent to which findings can be generalized to other settings or environments. |

| External | Temporal Validity | Extent to which results can be generalized across different time periods. |

| External | Interaction Effects | When the effect of the treatment depends on specific participant or setting characteristics. |

| External | Sampling Bias | When the sample does not accurately represent the target population. |

| External | Reactive Effects | When participants change their behavior because they know they are being studied (Hawthorne effect). |

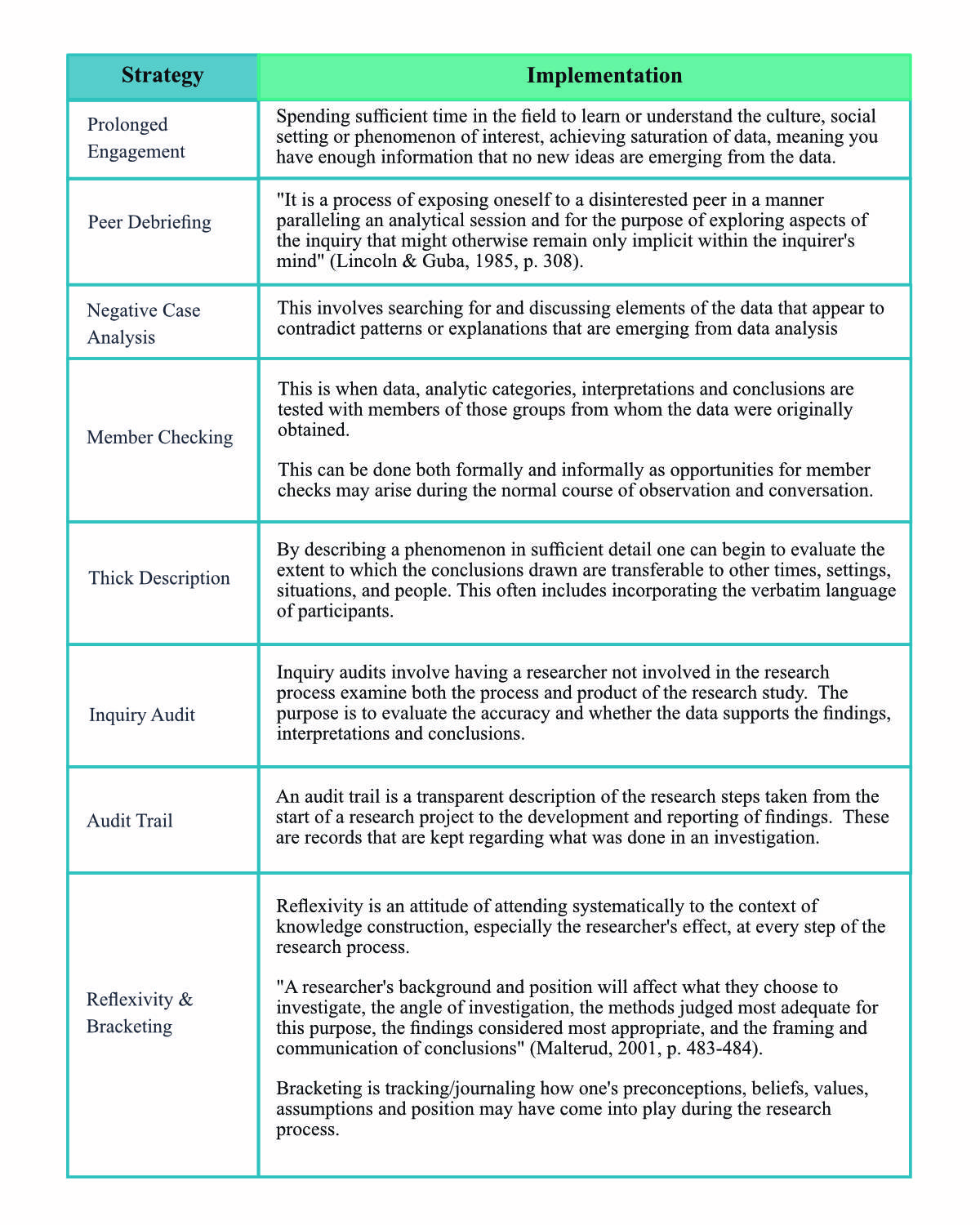

Assessing trustworthiness in Qualitative Research

When analyzing qualitative research, we don’t discuss strengths & limitations in the same language, rather we consider trustworthiness. Trustworthiness is a quality reflected in qualitative research that ensures the research is conducted in a credible way; a way that should produce confidence in the findings. To analyze the trustworthiness of qualitative research, you are looking at four core areas: Credibility, Transferability, Dependability, and Confirmability. Credibility ensures the findings are believable, trustworthy and accurate and asks the question, how confident am I in the “truth” of these findings? A researcher or evaluator can increase their credibility through several methods such as prolonged engagement, peer debriefing, negative case analysis, & member checking. Transferability & dependability are like the idea of generalizability; it is the extent to which the findings of a study can be applied or transferred to other contexts, settings, or populations beyond the specific study sample, and asks, do these findings have applicability in other contexts? And are the findings consistent & repeatable? Dependability is the extent to which research findings are stable and consistent over time. Transferability & dependability are strengthened through thick description and an inquiry audit. Finally, confirmability is the degree to which the findings of a study are shaped by the participants and not researcher bias, motivations, and personal interests. Researchers can protect against these limitations through an audit trail, reflexivity and bracketing.

Contemporary Analysis, Multicultural validity (peer reviewed & beyond)

Validity forms the foundation for making accurate judgments about how theory applies to a given issue and determining appropriate actions based on our confidence in shared knowledge (Kirkhart, 2010). Building on this, scholars have emphasized the importance of a multicultural validity model that explicitly incorporates cultural considerations into evaluation and research (Hood, Hopson, & Kirkhart, 2015; Kirkhart, 2005, 2010, 2013). Multicultural validity refers to the trustworthiness of our understandings, decisions, and their consequences when examined across multiple and intersecting dimensions of cultural diversity (Kirkhart, 2010).

This framework highlights five key dimensions, methodological, experiential, relational, theoretical, and consequential, that help identify factors that either strengthen or weaken validity (Kirkhart, 2013). Validity is strengthened when evaluation theory supports the thoughtful selection of epistemologies, methods, and procedures that account for cultural diversity and guard against culturally bound bias. Conversely, it is weakened when culture is overlooked or when diversity is treated through simplistic or stereotypical assumptions (Kirkhart, 2005).

At its core, epistemology, the study of how we know what we know, shapes theory development. It urges practitioners to ground their understanding in the perspectives of those most directly connected to the issue, while also examining their own biases and engaging in reflexive practice to critically evaluate the processes by which knowledge is constructed (Phipps, 2016).

The table below outlines different justifications and threats associated with each domain.

While you may not be able to fully assess every domain of multicultural validity in the existing literature, aim to address them as thoroughly as possible. This framework can also serve as a self-check for your own project to ensure you are maintaining multicultural validity throughout your work.

Kirkhart (2013) suggests using a culture checklist as a guide—but not as a rigid, step-by-step procedure or a list of cultural “do’s and don’ts” (Symonette, 2004). Instead, it is meant to prompt evaluators to intentionally consider cultural factors in the work of others and in their own projects, adapting the checklist to fit the specific context. The items can be addressed in any order, and you may need to create a tailored version for your particular evaluation.

You can use the Multicultural Validity Checklist [Word doc] to support your analysis and reflection.

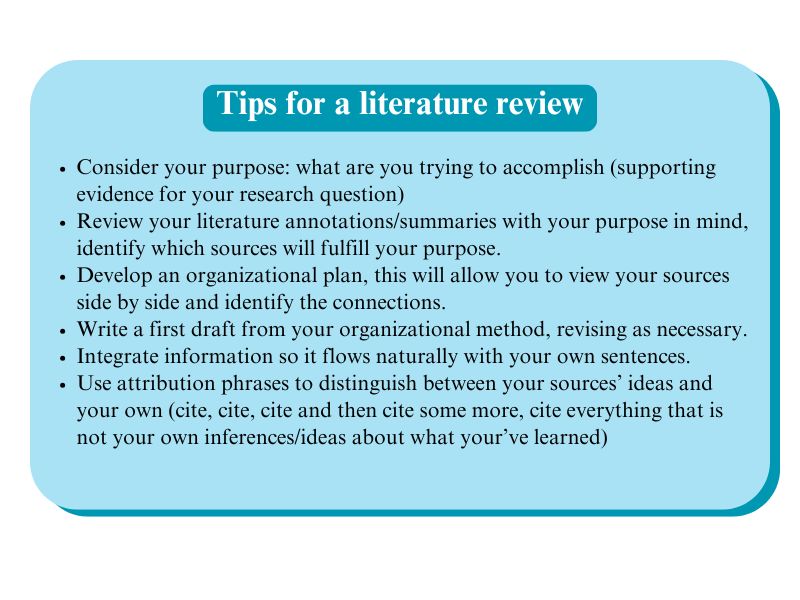

Constructing the Review

Once you have gathered what you need for the literature review, with the caveat that you may have to go back to the literature once you begin to organize to fill in the gaps, you will want to choose an organizational method for your literature. The primary goal of an organizational method, besides being organized, is data reduction. If you have 10 – 15 articles to synthesize, and they are each 20 pages long, reducing that to less pages is going to help manage the writing process. There are many ways to get organized, and if you have a process that works for you, use it. However, if you are new to this type of writing we will provide two techniques below that can help.

Annotated Bibliography

You may already be familiar with the term annotated bibliography. Traditionally, annotations are written as short paragraphs that summarize the key points from each source. If you have not worked with this process before, an annotated bibliography template [Word doc] is provided for you. In this version, the template is formatted as a table that prompts you to capture the most important details from each source. You can use the table as is or adapt your notes into paragraph form if you prefer.

The table guides you to identify:

-

The research question

-

The author’s purpose

-

Strengths and limitations of the methodology

-

Any additional limitations noted by the author

-

The usefulness of the source for your project

By using this format, you can condense 15 articles into about 15 pages of focused notes, making the material much easier to manage. You can also review several linked examples of annotated bibliographies based on different research designs.

Outline

The other tool provided here is the use of an outline. You will find the provided template is outlined in accordance with your final proposal assignment. In using this outline, you can highlight the most important elements of the literature and insert them into the outline where they belong. It is likely that one article may be relevant in several sections of the outline, that is okay. It’s about organizing your information into a simpler format to prepare to write. These tools can also be used in tandem. Click here for a literature review outline template [Word doc], and here for an outline example.

Outline

- Introduce social problem: define, scope, prevalence

- Article A/B/C viewpoints comparing their findings/theories

- Introduce Historical perspective, Theory of the problem

- Article A/B/C viewpoint comparing their findings/theories

- Introduce the Response, Theory of Change

- Article A/B/C viewpoint comparing their findings/theories

- Analyze the strength of the evidence

- Article A/B/C demonstrating the validity of your evidence

- Discussion and Conclusion

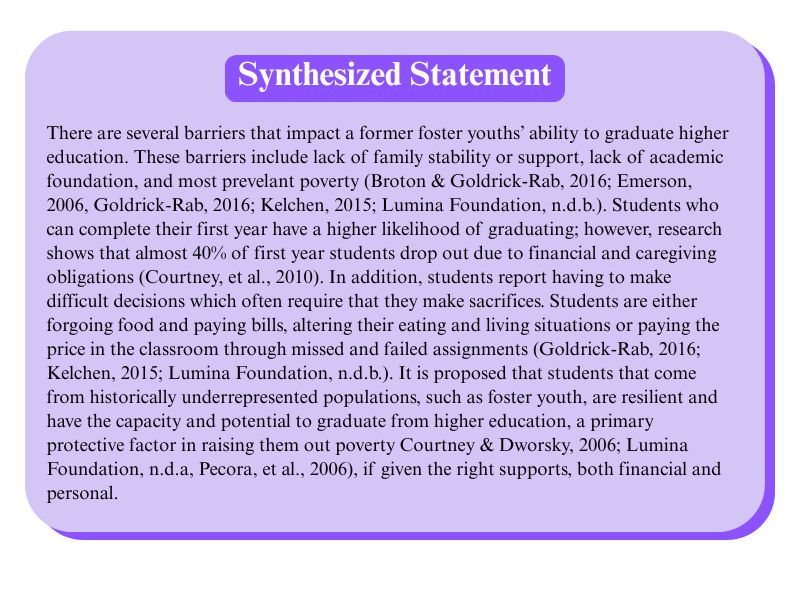

Synthesis of the Literature

One of the primary goals of the literature review is to give your reader a well-rounded, evidence-based understanding of the social issue, drawn from multiple sources, through synthesized writing. Synthesis means combining two or more sources to build a clearer, more complete picture.

Think of synthesis like assembling a puzzle: each source is a piece, and by identifying how the pieces fit together, you reveal the full image. You already use this skill in daily life, when you watch the news or a TikTok video and compare it to your own lived experience, or when you reflect on the differences between a favorite and least favorite supervisor. In your literature review, you will apply the same process, making explicit the connections and relationships among your sources.

This approach allows you to draw conclusions about what is currently known, providing the foundation to justify your project, either by filling a gap in the literature or by replicating research to strengthen its validity. Keep in mind that no single source should be treated as definitive proof. Instead, you build credibility by offering enough well-supported evidence to substantiate your claims and ideas.

Steps to Synthesize

-

Group related sources

-

Find studies that address similar themes, methods, or findings.

-

Example: Articles about trauma-informed care in schools vs. in child welfare.

-

-

Identify relationships

-

Compare: Where do sources agree?

-

Contrast: Where do they differ?

-

Add context: How does one study build on or challenge another?

-

-

Integrate your perspective

-

Don’t just list findings—explain how they connect and why it matters for your project.

-

Example: “While Smith (2020) and Lopez (2021) both found improved outcomes, Smith’s sample size was much smaller, which limits the generalizability.”

-

-

Write in blended sentences

-

Combine ideas from multiple sources in a single paragraph.

-

Example: “Several studies (Jones, 2019; Kim & Patel, 2020; Williams, 2021) demonstrate that peer mentoring reduces school dropout rates, though the degree of impact varies by program structure.”

-

-

Connect to your research purpose

-

Use synthesis to highlight gaps or support for your planned work.

-

Example: “Although these studies show promising results, none address rural communities, suggesting a gap that my project will explore.”

-

Tips for Effective Synthesis:

-

Use transition words like “similarly,” “in contrast,” “building on,” or “however” to link ideas.

-

Keep your voice present—don’t let your paper become a string of quotes.

-

Aim for at least three sources supporting each key point in your literature review.

Integrating the Evidence

The integration section of your literature review functions as its conclusion. Here, you bring together all the knowledge you’ve gathered and provide a final synthesis. Your goal is to highlight the most critical points from your review, focusing on how they justify your project. This section should be well-cited, clearly connecting the evidence to your ideas and conclusions.

Identify any gaps in knowledge or research limitations only if you plan to address them in your project. Highlighting gaps you cannot fill is not an effective strategy, save those ideas for a future directions section in a later semester.

In some cases, your topic may not have significant gaps because it has been extensively researched. That’s okay. In this situation, your role is to replicate existing studies to strengthen the evidence base. While new ideas often receive more attention, replication is essential for building trust in theories and practices. To take this approach, emphasize the strengths in the literature you want to build on, while also acknowledging potential challenges your project may face.

For example, research consistently supports Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) as an effective treatment. By replicating other studies to test CBT’s effectiveness, whether your findings confirm or challenge the theory, you contribute valuable evidence to the field.

You will end this section with a clear, concise statement of your proposed project, its purpose, and how it is grounded in the literature you have reviewed.

Chapter Summary & What’s to Come

Chapter 3 presented in-depth information on analyzing research and writing a theory-based literature review. Check out our glossary if you need a refresher on any of the key terms used throughout this chapter. Remember

- Writing is a process and a key social work skill. Writing literature reviews can be particularly challenging. Use the resources on annotated bibliographies and outlining to help you create structure and integrate critical thinking.

- An essential aspect of the literature review is integrating the research you’ve reviewed with the project you intend to carry out.

In Chapter 4: Implementation Planning, we talk through the details of HOW you will conduct your project.