4 Implementation Planning

At this stage, you are ready to outline the “nitty-gritty” of your project – the who, what, where, when and how of your project’s implementation. Think forward to December or January, when your project has been fully approved by your internship agency and the Department of Social Work: what will you need to do first? Next? When will you do these things? Who will you need to collaborate with? For what purposes? What information will you need? How will you get that information? These are a few of the key questions you’ll need to tackle as you plan your project’s implementation. The guidance below should help you work through these questions and more.

At this stage, you are ready to outline the “nitty-gritty” of your project – the who, what, where, when and how of your project’s implementation. Think forward to December or January, when your project has been fully approved by your internship agency and the Department of Social Work: what will you need to do first? Next? When will you do these things? Who will you need to collaborate with? For what purposes? What information will you need? How will you get that information? These are a few of the key questions you’ll need to tackle as you plan your project’s implementation. The guidance below should help you work through these questions and more.

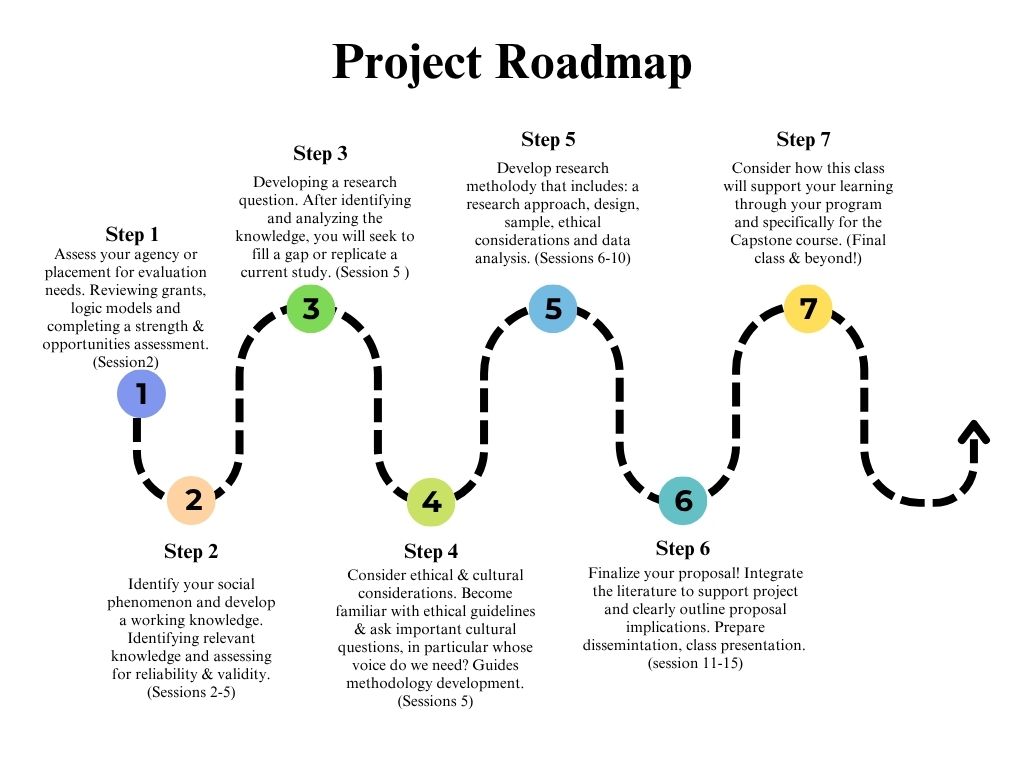

Identifying key steps in conducting the project

You’ve already established your project goal – the need it will meet and impact its intended to have within the organization. Now, we want to establish the scope of the project. The scope establishes the basic boundaries of your project – what you will deliver and when. In Capstone, the “when” is somewhat imposed given that your project must be wrapped up by the end of the Spring semester. The “what,” though, requires clarification. The “what” of your project will depend, in part, on the type of project you’ve chosen, and in part, on the needs and realities of organization. Let’s say the organization you are working with has identified the need for a more robust internship orientation process. To meet this need, you might opt to:

- create a program plan,

- develop recorded training videos, or

- create an intern handbook.

In option one, your deliverable would likely be a 25-30 page written document outlining key aspects of the internship program, including a “job” description, professional expectations, intern rights and responsibilities, outline of training and skill development processes, supervision and performance review processes, etc. In project option 2, you might create a series of onboarding videos for interns that focus on orienting them to their new role within the organization. And, in option 3, your deliverable might culminate in a comprehensive written document that new interns review during their onboarding process and use as reference throughout their time at the organization.

After you’ve defined the scope, you want to identify the agency information necessary to carry out this project. Depending on your project type, this information may include program goals and outcomes, strategic vision / direction, potential agency support people, resources available to you, etc. A quick note:: you may have identified some of this information already as you’ve worked on your project. As you gather additional information, be clear about how this information will be useful to your project; this will help you stay focused and ensure your asks of the organization are specific and meaningful.

Next, consider what logistics you might need to work out. For example, if you are developing a mindfulness training for elementary school teachers, you will need to know what dates are available for teacher training, how much time can be allotted, how many people might attend, the technology available, whether it will be in-person or virtual, and if in-person, what the physical space is like. You might also want to know if teachers have prior knowledge or experience with this training topic. While you don’t need answers to all these questions at this stage, thinking through logistical issues now will better prepare you for implementation later.

Note: Thoughtful planning is key to a successful project. But, as the cliché goes, even the best laid plans cannot account for all unforeseen circumstances. In Capstone, as in life, change is inevitable. A large part of our learning this year might be about flexibility & creative problem-solving.

Outlining how you will engage stakeholders

Throughout the planning and implementation of your project, you will engage with various stakeholders. These may be people you consult or partner with, or people who participate directly in your project, such as research or training participants. At a minimum, you will most likely consult with your internship supervisor to get their input into your project ideas, feedback on drafts of your work, access to resources needed for your projects’ implementation, or help with logistics (in some cases, another agency representative will serve this role).

Throughout the planning and implementation of your project, you will engage with various stakeholders. These may be people you consult or partner with, or people who participate directly in your project, such as research or training participants. At a minimum, you will most likely consult with your internship supervisor to get their input into your project ideas, feedback on drafts of your work, access to resources needed for your projects’ implementation, or help with logistics (in some cases, another agency representative will serve this role).

Depending on your project type, you may also need to collaborate with agency leaders such as the training manager, development director or fundraising specialist, marketing manager, program evaluator, executive director or board of directors. Additionally, you may opt to informally consult with peers to gain their input into how best to tailor your project to their needs. Or you may even convene a small group of service consumers to provide guidance on your project or to co-create the project with you. With the multitude of possibilities here, it can be important to think critically about whose voices are integral to the work and will create multicultural validity in your own project. Here are some resources that will get you started:

- CDC Framework summary: Workbook providing an overview of the CDC model for evaluation with a focus on community engagement.

- CDC identifying stakeholders: Guide for determining stakeholders who may have something to contribute at different stages of a project.

- CDC engaging evaluation stakeholders: Guide for how to engage stakeholders at different stages of a project.

Several models for community engagement have emerged in the last few decades that are relevant to Capstone projects in social work. We will focus briefly on two: (1) participatory action research and (2) participatory design. Participatory Action Research (PAR) is a strategic approach to social change that collaborates with community to design research for a more just world. PAR approaches help us to build alliances, produce knowledge informed by lived experience and disrupt power imbalances in how knowledge is traditionally generated (Cammarota & Fine, 2008). The PAR framework results in the use and creation of knowledge to both understand the world and transform it, through critical inquiry, critical reflection, and transformative action (Malorni, et al., 2022). If your project contains a research or evaluative component, please check out this worksheet for a series of relevant questions you may want to interrogate as you develop your project and seek stakeholder collaboration.

While PAR is intended to guide the activities of evaluation and research, its principles hold value for all projects that seek to integrate members of the community into determining the needs of community. Similarly, participatory design is a collaborative approach to creating products and services that better meet the needs of intended users. This approach is often referred to as co-design, co-production or cooperative design.

As in PAR, participatory design involves community members as thought partners throughout the design process. By collaborating with community in the brainstorming, testing and feedback phases of design, our products and services become more relevant, more useful, and more innovative. Community members may also experience greater ownership or buy-in when they’ve been an integral part of the development process. This framework has applications to a wide variety of fields including technology, architecture, urban planning, product design, graphic design, industrial design and health services. Learn more about participatory design from the Interaction Design Foundation.

Whatever approach to engagement you use, in this section of the proposal, you should discuss who you will engage with and for what purpose. Tell us how you will engage these stakeholders as well – individual meetings, informal conversations, soliciting feedback at a staff meeting, etc. If you intend to engage service consumers or community members more broadly, describe the role they will play within your project. A Stakeholder Map is useful tool for identifying direct and indirect stakeholders and relevant ways of engaging them.

Cultural and Ethical Considerations

As you plan for your project’s implementation, it is imperative to carefully consider the cultural and ethical issues relevant to the agency, community and project itself. The NASW Code of Ethics (2021) provides important grounding in our professional values, principles and ethical standards. This is a starting point for you. What values and ethical principles are prominent within your proposed project? What ethical dilemmas might arise as you implement your project? For instance, could a conflict of interest present itself as you carry out your project? If so, what values and principles will guide you as you navigate this conflict? As you move forward, will your project have to attend to how resources are allocated within the organization (such as in the development of a grant proposal or program plan)? How might decisions of resource allocation reflect principles of equity, justice, dignity and worth, competence, etc.?

Below are some common ethical issues that may arise in Capstone projects. Note, though, that this is by no means a comprehensive list.

- Confidentiality is the right to control access to our personal information. Confidentiality issues may arise in any group setting, including training, pilot groups of new curriculum, research and evaluation projects, interviews for social documentaries, etc.

- Privacy issues are common in research and evaluation projects and may arise in other projects in which personal information is involved.

- Informed Consent — All participants in your project should know what to expect, what will be asked of them, what their rights are, and what resources are available should they need support or have concerns; this is a requirement in evaluation projects in which primary data is collected and may be relevant in a number of other project types, such as social documentaries.

- Personal disclosure — While not always an ethical issue, some disclosures may cause emotional distress for participants in group settings, such as training or focus groups.

- Competence — The Capstone project asks you to take the lead on an issue of importance to the agency; as such, implementing your project may require you to deepen your expertise in a community, social issue, or practice modality. Awareness of gaps in your knowledge or skills and commitment to developing these areas are requisites of ethical practice.

- Empowerment and participatory practice are central to social work. We encourage you to incorporate these approaches within your capstone project but recognize that organizational realities and power dynamics may impede your ability to do so.

Be sure to describe how you intend to navigate the ethical issues or dilemmas that may arise within your project. For example, as discussed in earlier, let’s assume your project is a training for school personnel on incorporating trauma-informed principles into the school environment. As you consider the ethical dilemmas that may arise, perhaps you recognize that disclosures of trauma may occur during this training. Within a group setting, such disclosures may create privacy and confidentiality issues or emotional discomfort for participants. In your discussion, you should address how you will minimize the possibility of personal disclosures, establish boundaries around the sharing of personal experiences, and manage disclosures that do occur.

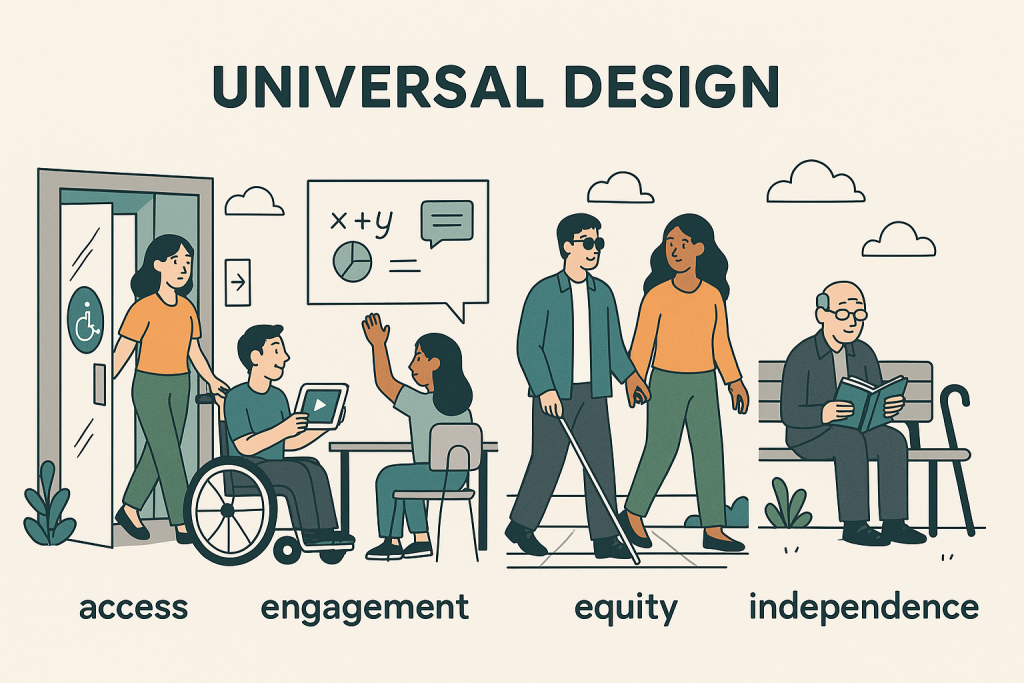

Accessibility

Accessibility is both a civil right and a legal requirement. In practical terms, accessibility is about designing and delivering products and services so that people of all abilities can use them. Such products and services should be equally easy to use for all people. We can foster accessibility by applying the principles of universal design to our work, which when taken together, encourage access, engagement, equity, independence, and enjoyment. As we develop new programs and curriculum, evaluate needs and services, or engage in training development, it is critical that we design in ways that attend to the diversity within our communities. While this includes people with cognitive, physical mobility, auditory, verbal, or ocular disabilities, universal design also considers economic status, language, age, cultural, educational and technical know-how (SeeWriteHear, 2025).

All that to say, every capstone project will have accessibility considerations. These may vary from document creation to arrangement of physical space to language use and choice of activities, to name a few. As you develop your implementation plan, consider the accessibility needs of your audience. How might universal design principles help you tend to your specific community and organizational context? For guidance on accessible design, check out the resources we’ve compiled.

Considering Research & Journalism Ethics

Depending on the nature of your project, you may also need to attend to research or media / journalism ethics. For example, research is often mistakenly assumed to be bias-free. However, the questions we ask, theories that guide us, and methodologies we use all reflect personal and professional paradigms that will inform and influence our efforts to understand the social world. In other words, we all hold both conscious and unconscious biases; it is our duty to understand, acknowledge and address the ways in which these biases impact our work. Other key principles that program evaluation projects must consider include:

- Respect for each person’s autonomy and safeguards for people with diminished autonomy; within research, this principle requires us to avoid coercion and undue influence and to take extra care with individuals who might be vulnerable due to marginalized social positionality, including age, education, system involvement, etc.

- Protection from harm – using methodological approaches that maximize the benefits of the research while minimizing potential harm; ideally, the research does not pose any greater risk than what we might encounter in everyday life. Some of our key measures to protect from harm include informed consent, data security, and debriefing.

- Justice – ensuring that the risks and benefits of research are allocated equitably among different groups; this principle asks us to consider how participants are selected for participation in research, whether inclusion of certain groups might further their exploitation or burdens, and how the benefits of research are made accessible.

Also ask yourself: how will you center culturally responsive, anti-racist and anti-oppressive principles within your project? Are there other theories, concepts, or frameworks relevant to your work? How do these align with our professional call to culturally relevant practice? How will they inform your project? How might you draw on cultural humility as you further develop your project?

Developing your Positionality Statement

A positionality statement is a description of how who you are informs what you do. Such statements highlight your key social identities and relevant familial and community context, and your professional framework will inform your work. In crafting a positionality statement, you will need to consider the biases that may arise based on your positionality and the commitments you hold as a social worker. If you struggle to identify your biases, consider taking an Implicit Association Test.

A positionality statement is personal and should reflect your authentic assessment of the factors likely to influence your project and your professional boundaries around what is appropriate and meaningful to reveal. Some positionality statements include:

- Description of your lenses (philosophical, personal, cultural, theoretical beliefs & perspective through which you view the project)

- Potential influences on the project (such as age, political beliefs, social class, race, ethnicity, gender, religious beliefs, previous career, etc.)

- Your chosen or pre-determined position about community, agency, or participants in the project (e.g., as an insider or an outsider)

- The project context (organization, community, etc.)

- An explanation as to how, where, when & in what way the above might influence the Capstone process

Remember: while this exercise calls us to deep personal reflection, YOU alone determine what to reveal when crafting your positionality statement. Be honest, be intentional, and set boundaries that are appropriate for you and your audience.

Consider the following questions as you engage in developing your statement:

- Locate yourself about the subject.

- How does who I am inform how I think about or approach this topic of study?

- What personal experiences or biases are essential for me to remain aware of as I engage with this topic?

- How does my cultural background affect my approach?

- Locate yourself about the community.

- What is my relationship with key stakeholders?

- What insider/outsider perspectives do I bring

- Locate yourself about the context/process

- What is my role within this space?

- What is my role within the process?

Note: the above questions were developed through reflection on the following resources:

Just Tell Me What I Need to Know: Reflexivity & Positionality Statements

Additional Resources are available in the Canvas Course.

Specific Considerations for Each Project Type

This section describes the additional topics you need to address based on your specific project type. Please ONLY attend to the instructions associated with your project (for example, if you are doing a social documentary, ignore the instructions for grant proposals, trainings and curriculum, and public education campaigns).

Grant Proposals & Program Plans

In addition to the topics outlined above, grant proposals and program plans require attention to several other elements. Both depend on skills in collecting information from multiple sources, including financial records, evaluation reports, community statistics, and other agency documents. For example, most grants require documentation on:

- Organizational background and goals

- Inclusiveness of the organization

- Sustainability (what challenges and opportunities does the organization face, and how are they prepared to tackle them)

- Program description (population served, numbers served, services offered, and expected outcomes)

- Program plan (goals and objectives, activities, timeline, justification for the approach, budgets)

- Evaluation plan (how will you measure the impact of the program)

- The roles of the board of directors, volunteers, and key staff

One of the most important tasks you can undertake when applying for funding is identifying an appropriate funder. Your implementation plan should address how you will research potential funding opportunities, and how you will access relevant agency information on the elements noted above (i.e. – who will you need to talk to? How will you connect with those people?).

Like grant applications, program plans require a detailed description of goals and objectives, activities, stakeholders and collaborators, staffing and management criteria, budget, and evaluation needs. Program plans, however, are internal documents that detail the ins and outs of the program or project and serve as roadmaps for implementation. They are used for planning, coordination, and management to ensure everyone is on the same page.

The skills you’ve learned and practiced throughout graduate school – such as applying theory and research – will serve you well in thinking through the implementation plan. In particular, you may want to consider the use of an organizational analysis or logic model during the early stages of developing your grant proposal or program plan.

An organizational analysis can be a helpful framework for identifying the organizational background and goals, analyzing agency inclusiveness, establishing program or organizational sustainability, and outlining a program description. We recommend talking with your agency now to find out if they have completed organizational assessments in the past. If so, your plan may draw on and learn from those past assessments; however, if the agency has never employed an assessment practice, conducting one as part of your capstone project can provide critical insights into strengths and strategic opportunities for development. For a review of organizational assessment and tools to support one, see Chapter 2.

A logic model is another useful tool that organizations use to demonstrate key components of a program. A logic model is what it sounds like, a visual representation of your program logic. It asks you to identify the resources available to the agency, the way in which those resources are used (i.e. recruitment, programming, assessment and evaluation), and the outcomes expected from the use of the identified resources. It tells a story: What do you have? How do you use it? What results do you expect? Because of the simplified nature of a logic model, grantors appreciate the visual snapshot of your goals. You can read more about logic models and explore examples provided by the Center for Disease Control (CDC):

As with an organizational assessment, your agency may already have a logic model, and if they don’t, you may want to develop a plan to create one. As an important note, a logic model can represent all work done by an agency or could be broken down by different agency programs. The model you need will depend on the grantor and what you seek money to fund.

Training & Curriculum

Both training and curriculum should use learning objectives to guide the development of materials. Course objectives (curricula) are much broader in scope than module-level objectives (training). Where module objectives break down skills and knowledge into very specific, discrete skills, course objectives point more to overarching student understanding and higher-level thinking skills. Therefore, curriculums should use both overall learning objectives that relate to the curriculum goals. Also, they should include learning objectives to support that module’s content and are tied back to the overall objectives. In contrast, a training will only have one set of learning objectives. You should have a lot of experience to draw on in developing learning objectives. Just think back to any college course you’ve ever taken; this is standard practice in education and learning.

Both training and curriculum should use learning objectives to guide the development of materials. Course objectives (curricula) are much broader in scope than module-level objectives (training). Where module objectives break down skills and knowledge into very specific, discrete skills, course objectives point more to overarching student understanding and higher-level thinking skills. Therefore, curriculums should use both overall learning objectives that relate to the curriculum goals. Also, they should include learning objectives to support that module’s content and are tied back to the overall objectives. In contrast, a training will only have one set of learning objectives. You should have a lot of experience to draw on in developing learning objectives. Just think back to any college course you’ve ever taken; this is standard practice in education and learning.

Good course objectives will be specific, measurable, and written from the learner’s perspective. Here is a good formula for writing objectives:

- Start your course objectives with: By the end of the course, students will be able to:

- Choose an action verb that corresponds to the specific action you wish students to demonstrate

- Explain the knowledge students are expected to acquire or construct

- [Optional]: Explain the criterion or level students are expected to reach to show mastery of knowledge.

The most prevalent model used to develop educational learning objectives is Bloom’s taxonomy (1956). Bloom’s taxonomy presents a scaffolded model of student learning from gathering knowledge to identifying, applying, evaluating, and integrating concepts. More information on updated & revised models of Bloom’s Taxonomy are online.

Finally, curricula and trainings may include an evaluative component to the project. For training, you will be collecting data in real-time, with a few options for how you do this. You can evaluate the effectiveness of the training and/or knowledge or skill building of the participants as a post-training analysis or pre-post evaluation and/or to complete a pre-development needs assessment to ensure that the project caters to the needs of the population. For curriculum, you may also choose to and are encouraged to complete a pre-development needs assessment. A pre-development needs assessment is a great way to get feedback from stakeholders and provide them with a sense of buy-in to your project and allows you to create a meaningful and useful product that fully meets the needs of your population. You could also choose to create a standard post-evaluation to include with the curriculum and to be used by those who implement it.

Some examples of past student training and curricula include:

- Trauma Informed Care in clinical practice workshop

- Dispelling the myths of Latina help seeking training

- Identifying TBI’s in IPV populations training

- Grief curriculum at the intersection of loss and addiction

- Onboarding guide for new interns

- Social media literacy curriculum for high school students

Social Documentary

In addition to the topics outlined above, social documentary projects should discuss whether and how you will consult with the Journalism and Media Production (JMP) Department at MSU Denver. Will you meet with journalism faculty to request feedback on your plans this fall? Will you take the social work elective course on social documentaries? Do you plan to opt into the peer support partnership in which JMP students provide support on filming and editing your documentary?

As mentioned earlier, all capstone projects should consider equity, anti-racism, and anti-oppression. Within social documentary projects, it is particularly important to craft the story with care for people’s identities, cultural practices, and lived experiences. Here are some questions you may want to grapple with in developing your project:

- What perspective(s) will you uplift through this medium?

- What dominant narratives about people, communities, or issues might you deconstruct or counter through this project?

- What personal biases might inform your approach to this project? How will you illuminate these patterns for yourself?

For example, a capstone on consent in dating relationships among high school students needs to consider how the voices of young people will be centered. Will youth be interviewed in the documentary? If so, which youth identities and subcultures will be elevated? Will young people help craft the interview questions and topics? Will they recruit adults as allies in uplifting this issue within the community? How does society and the media typically portray young people’s relationships and understanding of sexual consent? How does this portrayal differ from young people’s reality within this community? How might your own understanding of and experience in relationships inform your storytelling approach?

Practical questions you should consider as you develop your social documentary include:

- Will you need a budget to support your project and, if so, how much and for what specific expenses?

- What equipment or materials are needed for the creation of this documentary? Where will you obtain these supplies?

- How will you identify and recruit potential participants for the documentary?

- How will you ensure informed consent for these participants? Please describe your information-sharing strategies (flyer, email, face-to-face invitation with script, etc.) and include your media release form as an appendix to your proposal (see template).

- What topics do you intend to explore within this documentary? If conducting interviews, how will you develop the interview questions? Please include some potential interview questions if relevant.

- If your participants are asked to speak on sensitive topics, how will you manage potential emotional reactions (i.e. – what skills and strategies will you use? Will you provide a list of resources to participants?)? How will you navigate privacy and confidentiality issues?

Remember: you will need to use media release forms with anyone who participates in your project (and obtain guardian permission for anyone under 18 years old). Please include this form with your project proposal. A standardized form is available to you in the online course resources.

Public Education Campaign

In addition to the topics outlined above, a public education campaign proposal should describe the goals of the campaign. Is the goal to shed light on a social issue, raise awareness of available services and resources, or encourage people to engage in action around a community need? For example, the goals of a public education campaign on mental health might include:

- dispelling myths around mental and behavioral health,

- reducing the stigma associated with mental illness and

- raising awareness of supports and resources.

A campaign to end dating violence might aim to:

- increase knowledge of warning signs,

- offer guidance on how to support a friend or

- inform people about the need for new laws to address the use of technology to stalk or track a partner.

Also consider the educational strategies you intend to use in your campaign. Will you create posters or infographics to distribute in public places? Will you write op-ed pieces for local newspapers or a blog for the agency’s website? Will you plan an event featuring speakers with expertise on the topic? Or create ads for social media platforms?

Be sure to describe your overall approach to messaging within this campaign. Your messaging is about the words, images, and tone you will use to connect with your audience. Your messaging should engage your target audience and call them to action around the issue of concern. It must also reflect the values and ethics of the organization. In other words, it should be “on brand.”

The strategies and messaging you choose also need to resonate with your intended audience. That means you will need to clearly define who your audience is. To narrow in on your target audience, you may want to assess who has the least knowledge or access to information on the social issue of concern. Or you may choose to focus on communities whose needs have been historically underrepresented in public education campaigns on this issue. Alternatively, you may want to consider who has the most power to impact the issue and target your message to those folks. This can be a particularly useful approach if you are hoping to influence policy or other decision-making processes.

Once you’ve identified your educational strategy, overall messaging and target audience, then you should begin to map out logistics. What resources will you need for this campaign and how will you obtain those resources? Who will you need to engage or coordinate with to conduct this campaign? If you’re using social media, which platforms and what will your schedule of posting be? Will you monitor how people are engaging with your content?

As with all of our work, equity & anti-oppression are central considerations within Public Education Campaigns. These tenets require us to bring a critical lens to our campaign. We can begin by engaging questions, such as:

- Who is most impacted by this issue or policy? How can I most effectively engage those most impacted?

- Whose voices will inform this campaign? Are there voices that need to be (de-)centered?

- How does my personal experience & social positionality impact the perspective I bring to this project? What are my commitments & how will they influence this work?

Remember: You are developing a proposal, so you don’t need to know all the answers, or exactly what you’ll include in your resource. Your goal in semester one is to create a plan that outlines the steps in the development of the resource, and demonstrates how you will accomplish each step, not a description of the final product, you will provide that later.

Crafting a Project Timeline

Now, consider the time it will take to complete the various activities involved in your project and plot out a tentative time frame for each activity. Remember: your purpose here is to map out key milestones and deadlines for your project chronologically. Taking a moment now to estimate the time needed for various tasks will help you stay organized and on track when things get busy. According to project management experts, timelines serve several other important purposes, including:

- Communicating your goal and process to collaborators

- Conveying a clear path forward toward the final result

- Maintaining a 10,000 ft. view so that you don’t get lost in the weeds

- Tracking the order of tasks

- Helping you switch gears when bumps arise along the path

Source: Above information from Teamwork.com.

Project timelines are often created in visual formats so that you can see what needs to be done, when, and in what order. To get started, you need a clear sense of the scope of your project. Your instructor’s expertise in project management will come in handy so please rely on them as a resource. Next you will identify your project’s milestones and determine what should happen first, second, third, etc. For example, if you are creating a grant proposal, your first step may be to identify potential funders that align with your organization’s mission and programmatic approach. Then you might gather key agency information such as budgets, revenue streams, key staff and Board membership, organizational history, accomplishments, and program goals. Once you’ve determined a prospective funder and gathered relevant information, you may begin completing the grant application.

At times, you may find it helpful to break the milestones down into smaller tasks. For example, grant applications include several sections: Organizational Background and Goals, Program Descriptions, Evaluation Plan, Description of Collaborations, Statement of Inclusiveness, Management and Governance, Sustainability Plan, and Budget. A helpful strategy might be to dedicate one to two weeks to writing each of the lengthier sections of the proposal; smaller sections might be doubled up and tackled later in the semester. This approach allows you to progress steadily over time and visualize your accomplishments along the way.

Using a Gantt Chart to Implement Your Project

A Gantt chart is a visual timeline that helps you organize your work, estimate how long each step will take, and see how tasks overlap or depend on each other. For this project, your Gantt chart will map out each stage of implementation across the semester so you can stay on track and meet your deadlines. The goal is not just to list tasks but to create a realistic, sequenced plan that makes the most of your time. The chart provides an at-a-glance view of dependencies, showing which steps must be completed before others can begin. When paired with backward design, the process starts with your final deadline and works in reverse to set realistic milestones for each stage. For example, if your final paper is due in Week 15, backward design prompts you to schedule data analysis several weeks earlier, data collection before that, and literature review completion even earlier. This approach ensures that each step is allocated sufficient time, deadlines are met, and the project flows logically from planning to completion.

The Gantt Chart Process

Step 1: Brainstorm Activities

List every activity you need to complete your project. Focus on quantity, not quality at this stage—don’t edit or judge your ideas yet. Think about the full process from preparation to final submission.

Examples: preparing consent forms, recruiting participants, conducting interviews, entering data, analyzing results, writing sections of your paper.

Step 2: Estimate Time for Each Activity

Decide how long each activity will realistically take (e.g., 1 day, 1 week, 3 weeks). Be honest—some tasks like prep work may be short, while others like data collection will take longer.

Step 3: Put Activities in Order (Backward Design)

Arrange your activities in a logical sequence. Start from your final deadline and work backward, asking:

-

What must be finished right before the final step?

-

Which tasks depend on others being completed first?

-

How will I know if I’m on track?

Mark dependencies (e.g., you can’t analyze data before you collect it). This is where backward design helps you see if your timeline is realistic and balanced.

Step 4: Synthesize Activities

Look for opportunities to combine related tasks without losing necessary detail. This keeps your chart manageable while still clear enough to track your progress.

Step 5: Create the Visual

Translate your ordered list into a visual timeline that shows when each activity will be completed over the 16-week term. The preferred format is by week, using Excel, a table, or another visual tool.

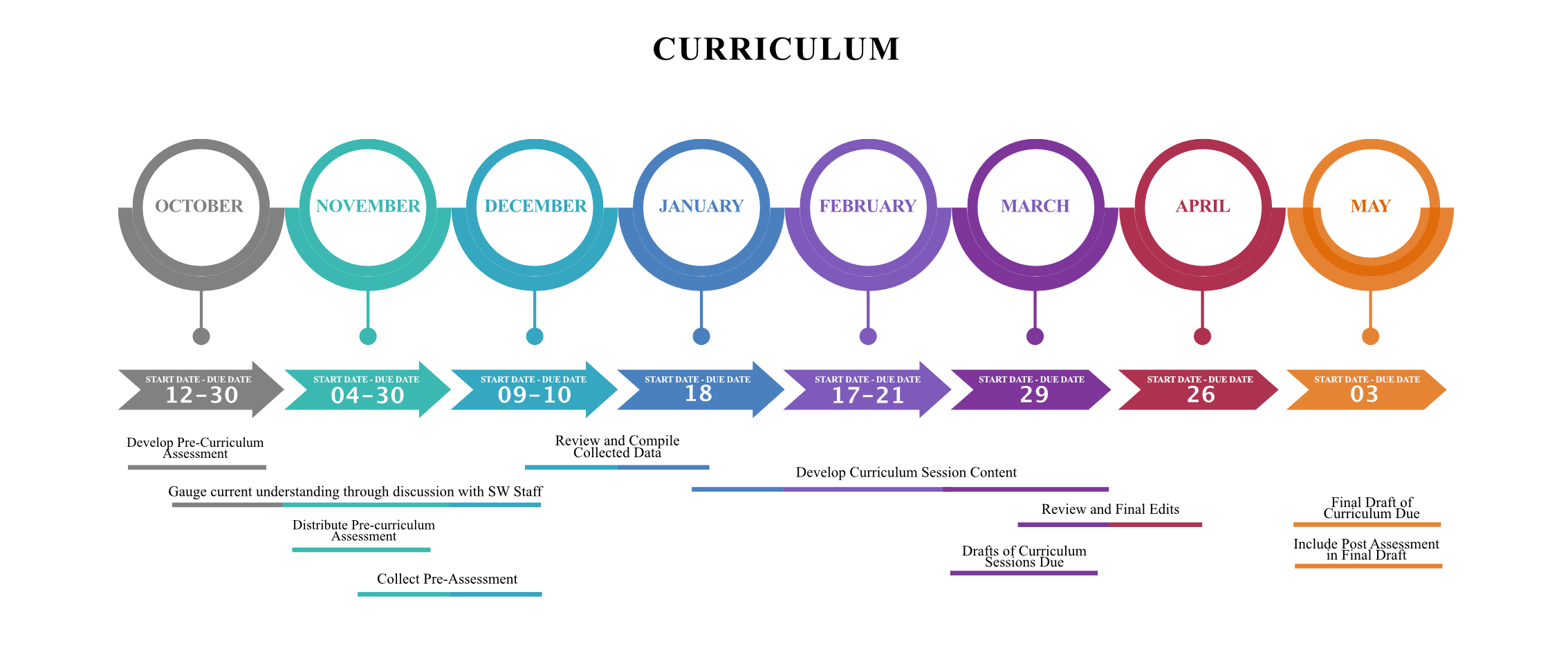

Your completed timeline will serve as a guide to your project’s implementation once it is officially approved. We recommend that you organize the timeline by weeks, as monthly may be too minimal and daily is too extensive. Below is an example project timeline for a Curriculum project for your reference.

You can create simple, straightforward timelines in Word documents using the Tables or SmartArt features. Alternatively, a wide variety of free templates are available online:

- Microsoft Office

- Canva

- Kanban Boards offer another visual option, with the added benefit of setting you up to track your progress over time. For more on Kanban Boards, also see: What is a Kanban Board and Miro.

A note of advice: Everyone is different regarding visual tools. If your timeline is too complicated or not aligned with your style of processing information, it won’t help you. Whatever approach you choose, please keep it simple and make sure it works for you.

Chapter Summary & What’s to Come

We covered a lot of ground in this chapter, from identifying key steps to engaging stakeholders to crafting a project timeline. Some highlight include:

- Participatory approaches, such as participatory action research and participatory design.

- Cultural and ethical considerations that arise in all capstone project

- Social positionality as an important influence on projects.

- Project-specific topics

Hopefully, the discussion, examples and resources offered throughout this chapter support you in developing a thoughtful, well-informed project. Coming up: an explanation of the final product description.