The first step of many PR campaigns is the initial research phase. First, practitioners identify and qualify the issue to be addressed. Then, they research the organization itself to clarify issues of public perception, positioning, and internal dynamics. This part is key to beginning any public relations campaign as it allows you to 1) determine what is the current state of the client and where it wants to be and 2) what are the needs and concerns of the client’s distinct stakeholder groups. These groups (also known as “audiences”) may include media outlets, constituents, consumers, and competitors. Finally, the context of the campaign is often researched, including the possible consequences of the campaign and the potential effects on the organization and its audiences. After considering all of these factors, practitioners are better educated to select the best type of campaign (e.g., issues advocacy, brand positioning, risk and crisis management).

Why do clients resist research?

It’s important to realize that clients may exhibit a resistance to doing upfront research before starting a campaign. In many ways this is reflective of the culture of capitalism, especially in the US, which equates time with money and also is focused on an anticipated return of investment at the outset of discussions of strategic imperatives. The author of this book (St. John) once visited a Fortune 500 company in St. Louis on an information interview. When he walked into the Marketing and Communication Director’s office, after a few moments of pleasant small talk, this director asked St. John, “So, how many projects do you work on in any average month?”

St. John paused, then said, “Well, outside of routine public relations smaller items–like sending out a news release or helping polish a speech, I have two major clients and I work on about 5-7 projects in total between them.”

The director leaned back in his seat and said, “About 5-7 projects, eh?” He paused and then pointed his thumb back to the cubicles behind him. “I’ve got people working on about 60 projects a month.”

From that example, it’s clear that corporate America has tended to prize activity over, for example, up front research. However, if you internalize that, before starting any public relations campaign one needs to do research, you will likely distinguish yourself from those subsumed in activity after activity. Clients pay for results, not activities.

Some of the reasons that clients will not support research

- It’s not in the budget.

- We don’t have enough time for it.

- We’re not going to evaluate the campaign, so why bother doing upfront research either?

- We don’t pay you for research, we pay you to get things done.

- Let’s see how things go this time and, if everything works out OK, then we can do research next time.

- We don’t have the right people to do the research.

- We have the right people, but they are busy on other tasks and project.

Real State/Ideal State Analysis

Let’s imagine that your boss sends the following text: “Our client (a major wealth advisor firm) is interested in exploring bitcoin and perhaps doing a special event about his company can move into this area. See what you can find out.” How do you even start? Before you can begin to understand the specifics of the research task itself, you need further clarification about the client’s expectations.

A real state/ideal state analysis will better position both you and the client for deciding what kind of public relations campaign the client may benefit from. It features a problem statement (Broom & Sha, 2013) that addresses the following components:

- It is written in the present tense. It describes the current situation without going into any suggestions about what could or should be done.

- It points out what is the source of the concern.

- It points to where the problem is most visible.

- It indicates when the problem occurs.

Untitled by Geralt is licensed under CC0. - It describes who is involved or affected

- It clearly states why this is a concern, both for the client and its stakeholders.

The ideal state then logically comes out of the factors identified in the real state analysis. That is, it should be written as in depth as necessary to draw a picture of what, ideally, the client would like to happen after the public relations campaign has been completed.

Here is how the real state/ideal state could appear regarding the bitcoin example above.

Town Square Wealth Advisors firm and the increasing interest in bitcoin

Real state: The firm is facing increasing inquiries over the last three months from high net-worth individuals (i.e., $1 million and above) who, when U.S. market indicies go down, are indicating they may wish to transfers some their assests into bitcoin. However, many of these investors indicate that 1) the firm is not educating investors on the pro and cons of such an investment and 2) does not partner with financial firms who are reputable in bitcoin investments. Several of our clients have indicated that this is making them re-think keeping their holdings in Town Square as they are concerned that the firm is “behind the times” and missing out on new sources of potentially high returns.

Ideal state: The firm has kept its current client base and is well-positioned to grow it number of clients because 1) it is seen as a trusted educational source on the risks and benefits of bitcoin investments and 2) it has established well-functioning working relationships with reputable firms who have a wide range of bitcoin investments. Customers, with a better education base, are doing bitcoin transactions through our firm partnership and are satisified with our knowledge and responsiveness.

Research modes

There are two main types of research modes: quantitative (or formal) research and qualitative (or informal) research. Quantitative research focuses on gathering data in numerical formats so that progress can be clearly delineated over time.

In that way, it tests propositions and provides valuable descriptive markers. In contrast, qualitative research examines how people make sense of phenomena; it too is descriptive, but concentrates on providing narratives about perspectives, values, and beliefs.

There is also another aspect of research gathering: primary and secondary. Primary data is information (whether quantitative or qualitative) that has been directly gathered through, for example, retail sales, surveys, focus groups and interviews. Secondary data may be similar types of information, but it has been gathered and presented by others (e.g., an opinion survey from Pew Research, news stories on how consumers rate your newest products).

Types of quantitative research

- Social media metrics: tracking and assigning numerical values to level of activities, followers and interactions.

- Content analysis: tracking and assigning numerical values to text and associated imagery and where/how the content appears. This involves training coders using a coding book; usually agreement between the coders of about 80 percent is required for validity of the results. This process does NOT code for audience attention or retention of the content.

- Surveys: these are queries of audiences who are subsets of a wider population. To be valid, samplings within this wider population must be randomized–that is, everyone within a subset population must have an equal probablity of being asked to participate in the doing the survey. Surveys can beadministered through email, traditional mail or via the phone. Online surveys can be conducted in a way that is randomized, but careful thought must be taken to make sure they are truly randomized.

- Databanks: organizations and governments track large sets of data. For example, for-profit organizations may track retails sales, numbers of customer inquiries and customer traffic in a bricks and motor store. Governments tracks traffic patterns, demographics and labor output.

Types of qualitative research

-

“Food Innovation 1” by Penn State is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0. Personal observation: this simply involves doing direct observations. For example, you may want to visit with customers and/or employees in your workplace. This is often referred to as “Management by Walking Around.” This approach allows you to see directly what is happening and how people talk about it. This also includes going to community meetings and trade association events, or even visiting with stakeholders where it is most convenient to them.

- Focus groups: this approach calls for bringing about 6-12 people together to get their impressions about a subject, issue, product, or service. Focus groups normally involve one facilitator who helps lead the discussion and another person who captures the threadlines of the participants’ observations.

- Key informants and one-on-one interviews: this approach is less formalized than the focus group; this often involves finding out the perspectives of opinion leaders like mentors, civic leaders, academics, social movement leaders and clergy. Such meetings can be one-on-one, or in small groups. This approach, however, normally works best when the information gathering is done through one-on-one interviews

- Community forums: consider these to be like a focus group on steroids. Normally, the number of people can be much higher than the 12 maximum for a focus group. This is because the attendees at a forum, unlike those at a focus group, may already be well versed on the subject to be discussed and are motivated to approach the matter in a particular way. Thiink of town hall meetings where a client may be seeking info on, for example, where to locate a new facility.

- Advisory committees: unlike a focus group, advisory committees consist of interested and motivated community members who see that they have direct stake in your organization. They operate as an advise and consult group; organizations may choose to use this forum to share ideas about new products and services or to ask committee members to provide ideas about solutions to problems both internal and external to the organization.

- Call-in telephone lines: these are normally toll-free and can be offered to customers in a more passive way (e.g., the number is offered as a customer service line, and is often printed on the packaging of the product) or can be offered in a more high-profile way (e.g., a server points out the number on your restaurant receipt, or you see a “How’s my driving?” sign on the back of a delivery vehicle, with the phone number clearly displayed.

One-on-one interviews are a valuable qualitative research approach. “Job Interview” is licensed under a Pixabay license. - Thematic analysis: as opposed to content analysis, this approach calls for tracking major thematic elements that appear in the information you have gathered. Rather than counting the appearances of certain items, this approach calls for segmenting information into various “buckets” (e.g., researching a company newsletter for over a four-year span has found that three major themes covered have been: 1) financial responsiblity, 2) employee commitment and 3) customer satisfaction). The buckets of information are then analyzed for thematic insights.

- Field reports: this approach is similar to “Management by Walking Around,” but it calls for a more structured approach. For example, field managers can observe processes/procedures/norms in a workplace and then draft a formal report. This approach should be paired with one of the others above, particularly quantiative approaches like surveys or databanks, as field reports can tend to be written with overly positive or negative observations with an eye to getting the client to react a certain way.

Positioning research for action planning

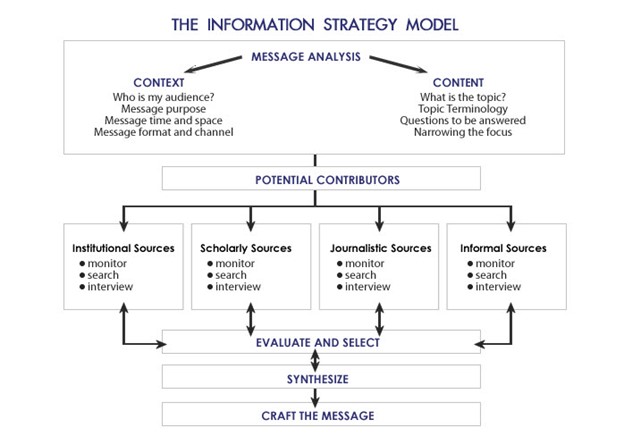

The research or “R” element of the RACE approach calls on careful real state/ideal state analysis at the front end. This is not a “nice to do” but a “must do.” Using the real

state/ideal state approach will position you and your client to better understand context and content. As the information strategy model shows, you can then pursue finding research materials through insitutional, scholarly, journalistic, and informal

sources. Depending on your client’s situation, you may pull from only one of these source areas, or a combination of these sources. It is then vitally important to carefully evaluate the information you receive from among these sources, then select the most important research material to help you synthesize for the client what is happening. Finally, you move into crafting the message and then working with your client to take that message and develop strategies. This sequence of steps logically leads you to Action Planning, or the “A” element of RACE, which is the subject of Chapter 3.

References

Broom, G. & Sha, B-L. (2013) Effective Public Relations (11th edition). New York: Pearson

Image Attribution

Untitled by Geralt is licensed under CC0.

“Analyzing Financial Data” by Dave Dugdale is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

“Food Innovation 1” by Penn State is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

“Job Interview” is licensed under a Pixabay license.

“The Information Strategy Model” by Hansen & Paul is licensed under CC BY 4.0.