The Communication element of strategic public relations focuses on how the PR effort will deliver its messages to the client’s key stakeholder groups. Once you have identified key messages for key audiences, then you begin to conceptualize how you will roll out those messages. In this chapter, we’ll hit broadly upon some of the aspects of Communication; this is because this element is normally the easiest for public relations practitioners to engage with. That is, PR pros often have notions of the kind of communication roll outs they have at their ready. Often, this may happen because public relations people start out their careers as public relations technicians and, in that capacity, they focus on the tactical elements of public relations. Therefore, in this chapter, you’ll see some important rollout planning elements to consider and what kinds of communication tactics public relations people can pull from.

Rollout (or tactical) planning

One of the most important aspects to consider as you plan message rollout is framing. This term signifies that you are: a) putting together succinctly the client’s message for distribution, and b) that you are also making sure the client’s message aligns with the needs and interests of each stakeholder group. There are several considerations to use as you solidify the messaging (Sha & Broom, 2013, p. 292):

- Use media and other distribution formats that the audiences are most likely to use.

- Make sure that the vehicle for communication is seen as highly credible to the audience.

- Minimize differences between what your client wants to communicate and the views of the stakeholder audiences.

- As events develop, modify the message as needed.

As you keep these tactical aspects in mind, there are six further elements to consider (Broom & Sha, 2013, p. 293):

- Understand how the audience sees the impact of your client’s messages and actions

- Focus on the proximity of the content of the messaging; that is, how much does what you are conveying relate to audience’s day-to-day lives?

- Consider the timeliness of the messaging — is what your addressing relevant now, or has the time passed your client by?

- What is the prominence of the matter you are addressing? Is it well-known or obscure?

- Is there some novelty to what you are communicating? The offbeat and/or unusual more readily captures audiences’ attentions.

- Is there some kind of conflict or drama in the situation you are addressing? Tension of this sort can make for ready-made attention among your stakeholders.

The importance of words

Words mean things, therefore, how we use them can make all the difference in the success of a public relations campaign. Additionally, how we use labels make all the difference. For example, an NPR reporter said he was “terrified” to ask an interviewee about how she dealt with a struggle in her life. More than likely, this reporter was not terrified about asking that question; that word means one is extremely afraid and filled with alarm. So, for example, a solider in warfare will likely be terrified, but not so much a reporter who has a difficult question for his interviewee. It’s more likely that the reporter meant that he was “apprehensive” or “feeling nervous” about asking that question. Additionally, many Americans use the words “I feel,” when they are really wanting to say “I think.” For example, a woman considering buying a big screen TV would say, “I feel that price is too high.” How does one have a “feeling” about a price and where it fits on the scale of affordability? Obviously, this is not about a feeling but about a fact — she knows that the price is higher than what hse has seen among competing TVs. The important thing to consider from these examples is this: be precise on your word choices and how you see them helping your client take steps toward acheiving their objectives and goals.

The meaning of the word “semantics” is not how it is understood in everyday language; for example, it’s not unusual to hear one person criticize another’s point of view by saying, “You’re simply playing word games and semantics.” In that use, the accuser is saying the other person is using words to manipulate or obscure. However, semantics actually is about the study of what words mean.

There are two important ways of understanding what words mean: denotative and connotative. The word “pig” denotes a four-legged animal that one may find on a farm or ranch. However, it also connotes something unfavorable: “Tim is such a pig when it comes to taking care of his apartment.” Clearly, the denotative understanding of pig means a sloppy person. One must be very careful of how different stakeholder groups understand the denotation and the connotations of a word. In one campaign course, a group of students proposed that a campaign for a fast-food restaurant should offer the message “Get your hustle on.” They intended their slogan to use the denotative meaning of hustle — moving fast — which fits with the idea of prompt providing of food. However, they didn’t realize that the word “hustle,” especially for older demographic groups, carries the connotative meaning of being a con artist!

Other important aspects of words involve symbols and stereotypes. Symbols are often combinations of words and images that stand for something else. For example, Smokey the Bear, who has been around for almost 80 years, is a readily identifiable image to most Americans. The image of the bear, with his ranger hat and his shovel in hand, immediate sends the message, “Only you can prevent forest fires.” Little if any words are needed; the word “Smokey” on his hat may often suffice. Stereotypes are another form of shorthand; in this case, however, they are words and images that offer generalities about groups of people. Although these stereotypes may come from some truths about some people, they are often inaccurate and harmful when they are attributed to a whole group of people. This is true whether they are negative stereotypes or seemingly positive stereotypes. A negative stereotype like “most Blacks are late for meetings,” is a destructive and harmful point of view. While it may be based on some truths — some Black people may, indeed, be repeatedly late, — this certainly isn’t a generalizable truth; many people from various backgrounds are repeatedly late for meetings. What about a positive-sounding stereotype? Is it really true that all Asians are good at math? No. While many may, indeed, be good at math, this statement is an overgeneralization that not only unfairly typecasts Asians into a certain trait, but also demeans the abilities of others from different cultures and experiences.

The bottom line here is: know your stakeholder groups and make sure to use appropriate messages that aren’t prejudicial to people and/or slant their viewpoints in unhelpful ways.

Understanding the five stages of adoption

When your audience is exposed to a new idea, product, or service, realize that your stakeholder audiences will need to go through stages of adoption. While you may have heard the phrase “early adopter” (i.e., individuals who are the first to take on a new idea, product, or service), even these individuals will follow the stages. For example, let’s consider Pete, who wants to buy a new car. He’s not quite sure what he wants, but he’s heard that electric vehicles are the way to go. Here is one way that Pete can follow the five adoption stages:

- Awareness: Pete is aware that there are several types of electronic and hybrid cars available. As he reads some more about these cars, he’s come to the conclusion that he wants a fully-electric vehicle that can have a range of 250 miles on a fully-charged battery.

- Interest: He reads up on about eight vehicles that seem to fit his requirement. He continues to gather specs about these vehicles and what auto reviewers say about each of them.

- Evaluation: He compares all the information that he has found about these vehicles and narrows them down to three vehciles that appear to be a good fit for him.

- Trial: He test drives the three vehicles and notices more of what he likes and doesn’t like about each. He sees one vehicle as standing out above the others.

- Adoption: Pete purchases that vehicle.

The Seven Cs of public relations communication

Prior to deciding what communication tactics to use for a public relations campaign, it is vital to consider factors that will likely influence the effectiveness of the campaign’s Communication element. Here are seven Cs (Broom & Sha, 2013, pp. 308-309) that a public relations professional can use to help decide on the tactics that will be optimal for the campaign:

- Credibility: How believable is the originator of the messages? If the messages are coming directly from the organization, how credibile the organization regarding the subject matter? If the message is being primarily carried by a third-party (e.g., a celebrity, a high-profile person in the community, a subject matter expert), how believable is that third party on the subject matter? If your stakeholder audiences don’t have confidence in the organization and/or third-party messengers, the public relations campaign is hampered from the outset.

- Context: Is the environment conducive for individuals receiving the messaging? That is, how well do the messages of the campaign square with the lived experience of the various stakeholder groups?

- Content: How well are the messages relevant and useful to the stakeholder groups? Moreover, how compatible are these messages to the values of each stakeholder group? Messages that are not meaningful and pertinent to these audiences will likely be ignored.

- Clarity: How clear is the messaging? Do the words have the same meaning for the sender as for the stakeholders (e.g., differences between connotations and denotations)? Can the messages be readily conveyed with brevity and, for example, be offered as themes or slogans?

- Continuity (and consistency): Can the messages be repetitively communicated and done so with one voice? If so, does the message have sufficient consistency?

- Channels (or vehicles): Can the messages be relayed through communication channels that stakeholders use and find credible? Different channels (e.g., social media, print, video) have different strengths and weaknesses regarding the encoding of the campaign’s messages and the various stakeholder groups’ decoding of the messages. Be wary about trying to convince a stakeholder group who normally uses print to find your messaging on social media. Understand what your target audiences find most valuable for a communication channel and structure your messages for that channel.

- Capability (of the audience): Can the messages be readily decoded by the audience, or are they filled with jargon or technical or abstract elements that stretches the capability of the stakeholders? If the messaging requires signficant discretionary effort on the part of the stakeholders, the campaign will likely struggle.

Common communication tactics

Publications: These can be directed to internal (inside the organization) audiences or external audiences. The external audiences may include customers, community members, political offices and the news media. For internal audiences, newsletters are a good way to keep employees up to date on organizational strategies and activities. External audiences may be of different types — for example, employees, volunteers, stockholders — and, depending on organizational priorities and resources, there may be a newsletter for each audience, or a combination of these audiences. Note: a particularly important publication for many organizations is the annual report; this format provides to stakeholders a yearly accounting of organizational activities and how those measures relate to the organization’s goals.

Speeches: Management may often find that they need to present the organization’s view of events through speeches at events. Public relations people are often a natural for providing this communication tactic as 1) they know the goals, visions and objectives of the organization, 2) they have developed an “ear” for how different managers speak, and can write the speech in a way that is true to the speaker and 3) they know how to structure a speech to both grab, and keep, an audience’s attention. At times, public relations people may take the speech and use it to inform other materials like backgrounder sheets (background information on an organizational viewpoint, product, or service and position papers (documents which lay out an organizational stance, customarily regarding a matter under review by political officials).

News media stories (also known as media relations): Public relations professionals are well-positioned to provide information to traditional and emerging news outlets. Such information is often first sent out to the media through a format known as the news release. Effectiveness in this area calls upon public relations practitioners to understand what the news outlet covers, who their audience is, and how they like to receive news leads from PR people. In addition to a news release, doing media relations can require signficant flexibility across numerous formats, based on the media’s preferences. This can mean, for example, doing telephone and/or video conference calls with reporters who cover the client’s industry, or interacting with reporters at trade shows or special events. Some reporters appreciate media kits, which provides an extensive array of news materials both in text and visual formats. Successfully placing a story is known as “earned media”; in contrast, buying advertising space for the client is known as “paid media.” Surveys have revealed that stakeholder groups find earned media more persuasive than paid media.

Social media: This tactical area calls upon public relations people to 1) know how different social media platforms work, 2) who the audiences are for various trend lines in social media, and 3) how to best use text and/or visuals to help amplify the

client’s messages. It’s crucial for public relations people to avoid “sales” language in many of the social media platforms; users often find sales pitches distasteful on platforms that they expect to be focused on conversation and information sharing. Paying an “influencer” to talk about your client on social media is not public relations — it’s marketing. Asking an opinion leader to do a live-streamed interview about your client, and the opinion leader is not compensated, would be public relations.

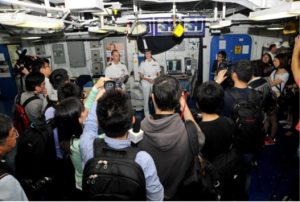

Special events: Sometimes also called “media events,” these are used to 1) get in-person attention and involvement from key stakeholder groups and 2) garner news media and/or social media attention. Compelling visuals are essential for garnering the attention of groups that could not attend and view the special event through mediated communication. So, if a special event is mostly about a speech being given by an organizations’ CEO, it will likely fail to garner traction through the media. However, if that speech is accompanied by a compelling backdrop for the speaker (e.g., bright colors and an audience listening from the behind the speaker), an interesting and perhaps offbeat venue (e.g., near a river that moves briskly, in front of a building that is almost completed) and any necessary props (e.g., a large simulation of a check, posters of children who rely on the organization’s services), the speaker may gain media attention. Special events often require extensive pre-planning checklists that most public relations professionals use to prevent any unwanted surprises. Note: such checklists tend to forget an important aspect of special events — make sure that the sound system used at the event is working an adequate to the venue. Nothing is more frustrating to have an event that is visually compelling, but the attendees can’t hear.

Advertorials: These are paid media placed in outlets that stakeholders follow. These are a version of an opinion column; they offer detail on the thinking and viewpoints of the organization without being filtered through reporters or other intermediaries. As this format normally calls for some extensive presentation of supporting materials and/or extensive explanations of the clients’ positions, advertorials most often appear in text format, either in a printed newspaper, for example, or a website.

Miscellaneous other supportive approaches include:

- Flyers and brochures.

- Inserts into newsletters, statements, or bills.

- Bulletin boards.

- Telephone hotlines.

- Email (note: this approach can be difficult as emails may be caught in recipients’ spam filters).

- Streaming video (either pre-recorded or live)

References

Broom, G. & Sha, B-L. (2013) Effective Public Relations (11th edition). New York: Pearson

Image Attribution

“CEO Brian Taylor Delivers State of the Port Address” by JAXPORT is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

“Preparing the media kit” by Irina Souiki is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

“Media tour 130415-N-HU377-23” by the United States Navy is licensed under CC0 Public Domain.