17

Donelson R. Forsyth

This chapter is from:

Forsyth, D. R. (2021). The psychology of groups. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/trfxbkhm

The Psychology of Groups

Psychologists study groups because nearly all human activities—working, learning, worshiping, relaxing, playing, and even sleeping—occur in groups. The lone individual who is cut off from all groups is a rarity. Most of us live out our lives in groups, and these groups have a profound impact on our thoughts, feelings, and actions. Many psychologists focus their attention on single individuals, but social psychologists expand their analysis to include groups, organizations, communities, and even cultures.

This module examines the psychology of groups and group membership. It begins with a basic question: What is the psychological significance of groups? People are, undeniably, more often in groups rather than alone. What accounts for this marked gregariousness and what does it say about our psychological makeup? The module then reviews some of the key findings from studies of groups. Researchers have asked many questions about people and groups: Do people work as hard as they can when they are in groups? Are groups more cautious than individuals? Do groups make wiser decisions than single individuals? In many cases the answers are not what common sense and folk wisdom might suggest.

The Psychological Significance of Groups

Many people loudly proclaim their autonomy and independence. Like Ralph Waldo Emerson, they avow, “I must be myself. I will not hide my tastes or aversions . . . . I will seek my own” (1903/2004, p. 127). Even though people are capable of living separate and apart from others, they join with others because groups meet their psychological and social needs.

The Need to Belong

Across individuals, societies, and even eras, humans consistently seek inclusion over exclusion, membership over isolation, and acceptance over rejection. As Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary conclude, humans have a need to belong: “a pervasive drive to form and maintain at least a minimum quantity of lasting, positive, and impactful interpersonal relationships” (1995, p. 497). And most of us satisfy this need by joining groups. When surveyed, 87.3% of Americans reported that they lived with other people, including family members, partners, and roommates (Davis & Smith, 2007). The majority, ranging from 50% to 80%, reported regularly doing things in groups, such as attending a sports event together, visiting one another for the evening, sharing a meal together, or going out as a group to see a movie (Putnam, 2000).

People respond negatively when their need to belong is unfulfilled. For example, college students often feel homesick and lonely when they first start college, but not if they belong to a cohesive, socially satisfying group (Buote et al., 2007). People who are accepted members of a group tend to feel happier and more satisfied. But should they be rejected by a group, they feel unhappy, helpless, and depressed. Studies of ostracism—the deliberate exclusion from groups—indicate this experience is highly stressful and can lead to depression, confused thinking, and even aggression (Williams, 2007). When researchers used a functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner to track neural responses to exclusion, they found that people who were left out of a group activity displayed heightened cortical activity in two specific areas of the brain—the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula. These areas of the brain are associated with the experience of physical pain sensations (Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003). It hurts, quite literally, to be left out of a group.

Affiliation in Groups

Groups not only satisfy the need to belong, they also provide members with information, assistance, and social support. Leon Festinger’s theory of social comparison (1950, 1954) suggested that in many cases people join with others to evaluate the accuracy of their personal beliefs and attitudes. Stanley Schachter (1959) explored this process by putting individuals in ambiguous, stressful situations and asking them if they wished to wait alone or with others. He found that people affiliate in such situations—they seek the company of others.

Although any kind of companionship is appreciated, we prefer those who provide us with reassurance and support as well as accurate information. In some cases, we also prefer to join with others who are even worse off than we are. Imagine, for example, how you would respond when the teacher hands back the test and yours is marked 85%. Do you want to affiliate with a friend who got a 95% or a friend who got a 78%? To maintain a sense of self-worth, people seek out and compare themselves to the less fortunate. This process is known as downward social comparison.

Identity and Membership

Groups are not only founts of information during times of ambiguity, they also help us answer the existentially significant question, “Who am I?” Common sense tells us that our sense of self is our private definition of who we are, a kind of archival record of our experiences, qualities, and capabilities. Yet, the self also includes all those qualities that spring from memberships in groups. People are defined not only by their traits, preferences, interests, likes, and dislikes, but also by their friendships, social roles, family connections, and group memberships. The self is not just a “me,” but also a “we.”

Even demographic qualities such as sex or age can influence us if we categorize ourselves based on these qualities. Social identity theory, for example, assumes that we don’t just classify other people into such social categories as man, woman, Anglo, elderly, or college student, but we also categorize ourselves. Moreover, if we strongly identify with these categories, then we will ascribe the characteristics of the typical member of these groups to ourselves, and so stereotype ourselves. If, for example, we believe that college students are intellectual, then we will assume we, too, are intellectual if we identify with that group (Hogg, 2001).

Groups also provide a variety of means for maintaining and enhancing a sense of self-worth, as our assessment of the quality of groups we belong to influences our collective self-esteem (Crocker & Luhtanen, 1990). If our self-esteem is shaken by a personal setback, we can focus on our group’s success and prestige. In addition, by comparing our group to other groups, we frequently discover that we are members of the better group, and so can take pride in our superiority. By denigrating other groups, we elevate both our personal and our collective self-esteem (Crocker & Major, 1989).

Mark Leary’s sociometer model goes so far as to suggest that “self-esteem is part of a sociometer that monitors peoples’ relational value in other people’s eyes” (2007, p. 328). He maintains self-esteem is not just an index of one’s sense of personal value, but also an indicator of acceptance into groups. Like a gauge that indicates how much fuel is left in the tank, a dip in self-esteem indicates exclusion from our group is likely. Disquieting feelings of self-worth, then, prompt us to search for and correct characteristics and qualities that put us at risk of social exclusion. Self-esteem is not just high self-regard, but the self-approbation that we feel when included in groups (Leary & Baumeister, 2000).

Evolutionary Advantages of Group Living

Groups may be humans’ most useful invention, for they provide us with the means to reach goals that would elude us if we remained alone. Individuals in groups can secure advantages and avoid disadvantages that would plague the lone individuals. In his theory of social integration, Moreland concludes that groups tend to form whenever “people become dependent on one another for the satisfaction of their needs” (1987, p. 104). The advantages of group life may be so great that humans are biologically prepared to seek membership and avoid isolation. From an evolutionary psychology perspective, because groups have increased humans’ overall fitness for countless generations, individuals who carried genes that promoted solitude-seeking were less likely to survive and procreate compared to those with genes that prompted them to join groups (Darwin, 1859/1963). This process of natural selection culminated in the creation of a modern human who seeks out membership in groups instinctively, for most of us are descendants of “joiners” rather than “loners.”

Motivation and Performance

Groups usually exist for a reason. In groups, we solve problems, create products, create standards, communicate knowledge, have fun, perform arts, create institutions, and even ensure our safety from attacks by other groups. But do groups always outperform individuals?

Social Facilitation in Groups

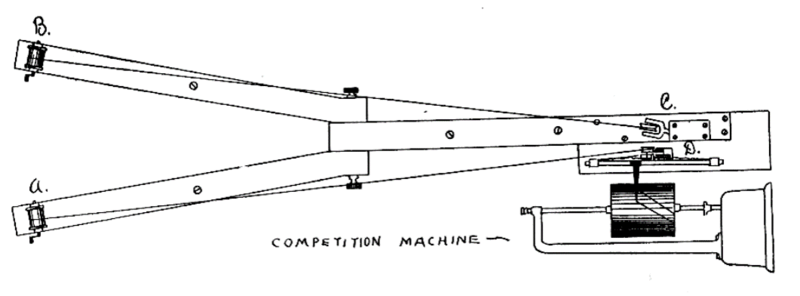

Do people perform more effectively when alone or when part of a group? Norman Triplett (1898) examined this issue in one of the first empirical studies in psychology. While watching bicycle races, Triplett noticed that cyclists were faster when they competed against other racers than when they raced alone against the clock. To determine if the presence of others leads to the psychological stimulation that enhances performance, he arranged for 40 children to play a game that involved turning a small reel as quickly as possible (see Figure 1). When he measured how quickly they turned the reel, he confirmed that children performed slightly better when they played the game in pairs compared to when they played alone (see Stroebe, 2012; Strube, 2005).

Triplett succeeded in sparking interest in a phenomenon now known as social facilitation: the enhancement of an individual’s performance when that person works in the presence of other people. However, it remained for Robert Zajonc (1965) to specify when social facilitation does and does not occur. After reviewing prior research, Zajonc noted that the facilitating effects of an audience usually only occur when the task requires the person to perform dominant responses, i.e., ones that are well-learned or based on instinctive behaviors. If the task requires nondominant responses, i.e., novel, complicated, or untried behaviors that the organism has never performed before or has performed only infrequently, then the presence of others inhibits performance. Hence, students write poorer quality essays on complex philosophical questions when they labor in a group rather than alone (Allport, 1924), but they make fewer mistakes in solving simple, low-level multiplication problems with an audience or a coactor than when they work in isolation (Dashiell, 1930).

Social facilitation, then, depends on the task: other people facilitate performance when the task is so simple that it requires only dominant responses, but others interfere when the task requires nondominant responses. However, a number of psychological processes combine to influence when social facilitation, not social interference, occurs. Studies of the challenge-threat response and brain imaging, for example, confirm that we respond physiologically and neurologically to the presence of others (Blascovich, Mendes, Hunter, & Salomon, 1999). Other people also can trigger evaluation apprehension, particularly when we feel that our individual performance will be known to others, and those others might judge it negatively (Bond, Atoum, & VanLeeuwen, 1996). The presence of other people can also cause perturbations in our capacity to concentrate on and process information (Harkins, 2006). Distractions due to the presence of other people have been shown to improve performance on certain tasks, such as the Stroop task, but undermine performance on more cognitively demanding tasks(Huguet, Galvaing, Monteil, & Dumas, 1999).

Social Loafing

Groups usually outperform individuals. A single student, working alone on a paper, will get less done in an hour than will four students working on a group project. One person playing a tug-of-war game against a group will lose. A crew of movers can pack up and transport your household belongings faster than you can by yourself. As the saying goes, “Many hands make light the work” (Littlepage, 1991; Steiner, 1972).

Groups, though, tend to be underachievers. Studies of social facilitation confirmed the positive motivational benefits of working with other people on well-practiced tasks in which each member’s contribution to the collective enterprise can be identified and evaluated. But what happens when tasks require a truly collective effort? First, when people work together they must coordinate their individual activities and contributions to reach the maximum level of efficiency—but they rarely do (Diehl & Stroebe, 1987). Three people in a tug-of-war competition, for example, invariably pull and pause at slightly different times, so their efforts are uncoordinated. The result is coordination loss: the three-person group is stronger than a single person, but not three times as strong. Second, people just don’t exert as much effort when working on a collective endeavor, nor do they expend as much cognitive effort trying to solve problems, as they do when working alone. They display social loafing (Latané, 1981).

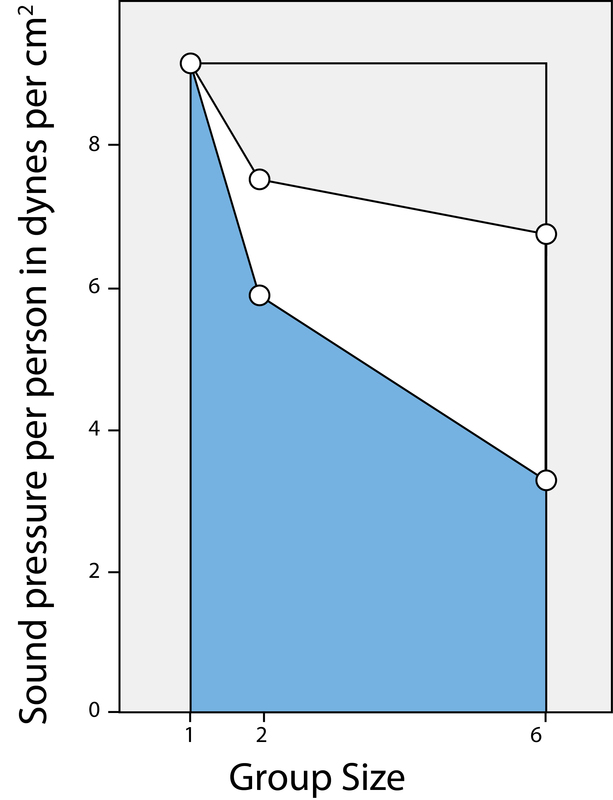

Bibb Latané, Kip Williams, and Stephen Harkins (1979) examined both coordination losses and social loafing by arranging for students to cheer or clap either alone or in groups of varying sizes. The students cheered alone or in 2- or 6-person groups, or they were lead to believe they were in 2- or 6-person groups (those in the “pseudo-groups” wore blindfolds and headsets that played masking sound). As Figure 2 indicates, groups generated more noise than solitary subjects, but the productivity dropped as the groups became larger in size. In dyads, each subject worked at only 66% of capacity, and in 6-person groups at 36%. Productivity also dropped when subjects merely believed they were in groups. If subjects thought that one other person was shouting with them, they shouted 82% as intensely, and if they thought five other people were shouting, they reached only 74% of their capacity. These loses in productivity were not due to coordination problems; this decline in production could be attributed only to a reduction in effort—to social loafing (Latané et al., 1979, Experiment 2).

Teamwork

Social loafing is no rare phenomenon. When sales personnel work in groups with shared goals, they tend to “take it easy” if another salesperson is nearby who can do their work (George, 1992). People who are trying to generate new, creative ideas in group brainstorming sessions usually put in less effort and are thus less productive than people who are generating new ideas individually (Paulus & Brown, 2007). Students assigned group projects often complain of inequity in the quality and quantity of each member’s contributions: Some people just don’t work as much as they should to help the group reach its learning goals (Neu, 2012). People carrying out all sorts of physical and mental tasks expend less effort when working in groups, and the larger the group, the more they loaf (Karau & Williams, 1993).

Groups can, however, overcome this impediment to performance through teamwork. A group may include many talented individuals, but they must learn how to pool their individual abilities and energies to maximize the team’s performance. Team goals must be set, work patterns structured, and a sense of group identity developed. Individual members must learn how to coordinate their actions, and any strains and stresses in interpersonal relations need to be identified and resolved (Salas, Rosen, Burke, & Goodwin, 2009).

Researchers have identified two key ingredients to effective teamwork: a shared mental representation of the task and group unity. Teams improve their performance over time as they develop a shared understanding of the team and the tasks they are attempting. Some semblance of this shared mental model is present nearly from its inception, but as the team practices, differences among the members in terms of their understanding of their situation and their team diminish as a consensus becomes implicitly accepted (Tindale, Stawiski, & Jacobs, 2008).

Effective teams are also, in most cases, cohesive groups (Dion, 2000). Group cohesion is the integrity, solidarity, social integration, or unity of a group. In most cases, members of cohesive groups like each other and the group and they also are united in their pursuit of collective, group-level goals. Members tend to enjoy their groups more when they are cohesive, and cohesive groups usually outperform ones that lack cohesion.

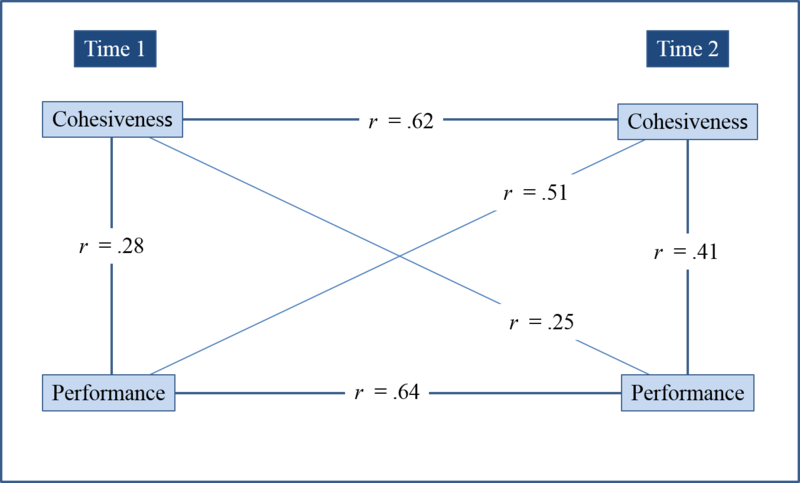

This cohesion-performance relationship, however, is a complex one. Meta-analytic studies suggest that cohesion improves teamwork among members, but that performance quality influences cohesion more than cohesion influences performance (Mullen & Copper, 1994; Mullen, Driskell, & Salas, 1998; see Figure 3). Cohesive groups also can be spectacularly unproductive if the group’s norms stress low productivity rather than high productivity (Seashore, 1954).

Group Development

In most cases groups do not become smooth-functioning teams overnight. As Bruce Tuckman’s (1965) theory of group development suggests, groups usually pass through several stages of development as they change from a newly formed group into an effective team. As noted in Focus Topic 1, in the forming phase, the members become oriented toward one another. In the storming phase, the group members find themselves in conflict, and some solution is sought to improve the group environment. In the norming, phase standards for behavior and roles develop that regulate behavior. In the performing, phase the group has reached a point where it can work as a unit to achieve desired goals, and the adjourning phase ends the sequence of development; the group disbands. Throughout these stages groups tend to oscillate between the task-oriented issues and the relationship issues, with members sometimes working hard but at other times strengthening their interpersonal bonds (Tuckman & Jensen, 1977).

Focus Topic 1: Group Development Stages and Characteristics

Stage 1 – “Forming”. Members expose information about themselves in polite but tentative interactions. They explore the purposes of the group and gather information about each other’s interests, skills, and personal tendencies.

Stage 2 – “Storming”. Disagreements about procedures and purposes surface, so criticism and conflict increase. Much of the conflict stems from challenges between members who are seeking to increase their status and control in the group.

Stage 3 – “Norming”. Once the group agrees on its goals, procedures, and leadership, norms, roles, and social relationships develop that increase the group’s stability and cohesiveness.

Stage 4 – “Performing”. The group focuses its energies and attention on its goals, displaying higher rates of task-orientation, decision-making, and problem-solving.

Stage 5 – “Adjourning”. The group prepares to disband by completing its tasks, reduces levels of dependency among members, and dealing with any unresolved issues.

Sources based on Tuckman (1965) and Tuckman & Jensen (1977)

We also experience change as we pass through a group, for we don’t become full-fledged members of a group in an instant. Instead, we gradually become a part of the group and remain in the group until we leave it. Richard Moreland and John Levine’s (1982) model of group socialization describes this process, beginning with initial entry into the group and ending when the member exits it. For example, when you are thinking of joining a new group—a social club, a professional society, a fraternity or sorority, or a sports team—you investigate what the group has to offer, but the group also investigates you. During this investigation stage you are still an outsider: interested in joining the group, but not yet committed to it in any way. But once the group accepts you and you accept the group, socialization begins: you learn the group’s norms and take on different responsibilities depending on your role. On a sports team, for example, you may initially hope to be a star who starts every game or plays a particular position, but the team may need something else from you. In time, though, the group will accept you as a full-fledged member and both sides in the process—you and the group itself—increase their commitment to one another. When that commitment wanes, however, your membership may come to an end as well.

Making Decisions in Groups

Groups are particularly useful when it comes to making a decision, for groups can draw on more resources than can a lone individual. A single individual may know a great deal about a problem and possible solutions, but his or her information is far surpassed by the combined knowledge of a group. Groups not only generate more ideas and possible solutions by discussing the problem, but they can also more objectively evaluate the options that they generate during discussion. Before accepting a solution, a group may require that a certain number of people favor it, or that it meets some other standard of acceptability. People generally feel that a group’s decision will be superior to an individual’s decision.

Groups, however, do not always make good decisions. Juries sometimes render verdicts that run counter to the evidence presented. Community groups take radical stances on issues before thinking through all the ramifications. Military strategists concoct plans that seem, in retrospect, ill-conceived and short-sighted. Why do groups sometimes make poor decisions?

Group Polarization

Let’s say you are part of a group assigned to make a presentation. One of the group members suggests showing a short video that, although amusing, includes some provocative images. Even though initially you think the clip is inappropriate, you begin to change your mind as the group discusses the idea. The group decides, eventually, to throw caution to the wind and show the clip—and your instructor is horrified by your choice.

This hypothetical example is consistent with studies of groups making decisions that involve risk. Common sense notions suggest that groups exert a moderating, subduing effect on their members. However, when researchers looked at groups closely, they discovered many groups shift toward more extreme decisions rather than less extreme decisions after group interaction. Discussion, it turns out, doesn’t moderate people’s judgments after all. Instead, it leads to group polarization: judgments made after group discussion will be more extreme in the same direction as the average of individual judgments made prior to discussion (Myers & Lamm, 1976). If a majority of members feel that taking risks is more acceptable than exercising caution, then the group will become riskier after a discussion. For example, in France, where people generally like their government but dislike Americans, group discussion improved their attitude toward their government but exacerbated their negative opinions of Americans (Moscovici & Zavalloni, 1969). Similarly, prejudiced people who discussed racial issues with other prejudiced individuals became even more negative, but those who were relatively unprejudiced exhibited even more acceptance of diversity when in groups (Myers & Bishop, 1970).

Common Knowledge Effect

One of the advantages of making decisions in groups is the group’s greater access to information. When seeking a solution to a problem, group members can put their ideas on the table and share their knowledge and judgments with each other through discussions. But all too often groups spend much of their discussion time examining common knowledge—information that two or more group members know in common—rather than unshared information. This common knowledge effect will result in a bad outcome if something known by only one or two group members is very important.

Researchers have studied this bias using the hidden profile task. On such tasks, information known to many of the group members suggests that one alternative, say Option A, is best. However, Option B is definitely the better choice, but all the facts that support Option B are only known to individual groups members—they are not common knowledge in the group. As a result, the group will likely spend most of its time reviewing the factors that favor Option A, and never discover any of its drawbacks. In consequence, groups often perform poorly when working on problems with nonobvious solutions that can only be identified by extensive information sharing (Stasser & Titus, 1987).

Groupthink

Groups sometimes make spectacularly bad decisions. In 1961, a special advisory committee to President John F. Kennedy planned and implemented a covert invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs that ended in total disaster. In 1986, NASA carefully, and incorrectly, decided to launch the Challenger space shuttle in temperatures that were too cold.

Irving Janis (1982), intrigued by these kinds of blundering groups, carried out a number of case studies of such groups: the military experts that planned the defense of Pearl Harbor; Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs planning group; the presidential team that escalated the war in Vietnam. Each group, he concluded, fell prey to a distorted style of thinking that rendered the group members incapable of making a rational decision. Janis labeled this syndrome groupthink: “a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action” (p. 9).

Janis identified both the telltale symptoms that signal the group is experiencing groupthink and the interpersonal factors that combine to cause groupthink. To Janis, groupthink is a disease that infects healthy groups, rendering them inefficient and unproductive. And like the physician who searches for symptoms that distinguish one disease from another, Janis identified a number of symptoms that should serve to warn members that they may be falling prey to groupthink. These symptoms include overestimating the group’s skills and wisdom, biased perceptions and evaluations of other groups and people who are outside of the group, strong conformity pressures within the group, and poor decision-making methods.

Janis also singled out four group-level factors that combine to cause groupthink: cohesion, isolation, biased leadership, and decisional stress.

- Cohesion: Groupthink only occurs in cohesive groups. Such groups have many advantages over groups that lack unity. People enjoy their membership much more in cohesive groups, they are less likely to abandon the group, and they work harder in pursuit of the group’s goals. But extreme cohesiveness can be dangerous. When cohesiveness intensifies, members become more likely to accept the goals, decisions, and norms of the group without reservation. Conformity pressures also rise as members become reluctant to say or do anything that goes against the grain of the group, and the number of internal disagreements—necessary for good decision making—decreases.

- Isolation. Groupthink groups too often work behind closed doors, keeping out of the limelight. They isolate themselves from outsiders and refuse to modify their beliefs to bring them into line with society’s beliefs. They avoid leaks by maintaining strict confidentiality and working only with people who are members of their group.

- Biased leadership. A biased leader who exerts too much authority over group members can increase conformity pressures and railroad decisions. In groupthink groups, the leader determines the agenda for each meeting, sets limits on discussion, and can even decide who will be heard.

- Decisional stress. Groupthink becomes more likely when the group is stressed, particularly by time pressures. When groups are stressed they minimize their discomfort by quickly choosing a plan of action with little argument or dissension. Then, through collective discussion, the group members can rationalize their choice by exaggerating the positive consequences, minimizing the possibility of negative outcomes, concentrating on minor details, and overlooking larger issues.

You and Your Groups

Most of us belong to at least one group that must make decisions from time to time: a community group that needs to choose a fund-raising project; a union or employee group that must ratify a new contract; a family that must discuss your college plans; or the staff of a high school discussing ways to deal with the potential for violence during football games. Could these kinds of groups experience groupthink? Yes they could, if the symptoms of groupthink discussed above are present, combined with other contributing causal factors, such as cohesiveness, isolation, biased leadership, and stress. To avoid polarization, the common knowledge effect, and groupthink, groups should strive to emphasize open inquiry of all sides of the issue while admitting the possibility of failure. The leaders of the group can also do much to limit groupthink by requiring full discussion of pros and cons, appointing devil’s advocates, and breaking the group up into small discussion groups.

If these precautions are taken, your group has a much greater chance of making an informed, rational decision. Furthermore, although your group should review its goals, teamwork, and decision-making strategies, the human side of groups—the strong friendships and bonds that make group activity so enjoyable—shouldn’t be overlooked. Groups have instrumental, practical value, but also emotional, psychological value. In groups we find others who appreciate and value us. In groups we gain the support we need in difficult times, but also have the opportunity to influence others. In groups we find evidence of our self-worth, and secure ourselves from the threat of loneliness and despair. For most of us, groups are the secret source of well-being.