19

Christia Spears Brown; Jennifer A. Jewell; and Michelle J. Tam

This chapter is from:

Brown, C. S., Jewell, J. A., & Tam, M. J. (2021). Gender. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/ge5fdhba

Introduction

Before we discuss gender in detail, it is important to understand what gender actually is. The terms sex and gender are frequently used interchangeably, though they have different meanings. In this context, sex refers to the biological category of male or female, as defined by physical differences in genetic composition and in reproductive anatomy and function. On the other hand, gender refers to the cultural, social, and psychological meanings that are associated with masculinity and femininity (Wood & Eagly, 2002). You can think of “male” and “female” as distinct categories of sex (a person is typically born a male or a female), but “masculine” and “feminine” as continuums associated with gender (everyone has a certain degree of masculine and feminine traits and qualities).

Beyond sex and gender, there are a number of related terms that are also often misunderstood. Gender roles are the behaviors, attitudes, and personality traits that are designated as either masculine or feminine in a given culture. It is common to think of gender roles in terms of gender stereotypes, or the beliefs and expectations people hold about the typical characteristics, preferences, and behaviors of men and women. A person’s gender identity refers to their psychological sense of being male or female. In contrast, a person’s sexual orientation is the direction of their emotional and erotic attraction toward members of the opposite sex, the same sex, or both sexes. These are important distinctions, and though we will not discuss each of these terms in detail, it is important to recognize that sex, gender, gender identity, and sexual orientation do not always correspond with one another. A person can be biologically male but have a female gender identity while being attracted to women, or any other combination of identities and orientations.

Defining Gender

Historically, the terms gender and sex have been used interchangeably. Because of this, gender is often viewed as a binary – a person is either male or female – and it is assumed that a person’s gender matches their biological sex. This is not always the case, however, and more recent research has separated these two terms. While the majority of people do identify with the gender that matches their biological sex (cisgender), an estimated 0.6% of the population identify with a gender that does not match their biological sex (transgender; Flores, Herman, Gates, & Brown, 2016). For example, an individual who is biologically male may identify as female, or vice versa.

In addition to separating gender and sex, recent research has also begun to conceptualize gender in ways beyond the gender binary. Genderqueer or gender nonbinary are umbrella terms used to describe a wide range of individuals who do not identify with and/or conform to the gender binary. These terms encompass a variety of more specific labels individuals may use to describe themselves. Some common labels are genderfluid, agender, and bigender. An individual who is genderfluid may identify as male, female, both, or neither at different times and in different circumstances. An individual who is agender may have no gender or describe themselves as having a neutral gender, while bigender individuals identify as two genders.

It is important to remember that sex and gender do not always match and that gender is not always binary; however, a large majority of prior research examining gender has not made these distinctions. As such, the following sections will discuss gender as a binary.

Gender Differences

Differences between males and females can be based on (a) actual gender differences (i.e., men and women are actually different in some abilities), (b) gender roles (i.e., differences in how men and women are supposed to act), or (c) gender stereotypes (i.e., differences in how we think men and women are). Sometimes gender stereotypes and gender roles reflect actual gender differences, but sometimes they do not.

What are actual gender differences? In terms of language and language skills, girls develop language skills earlier and know more words than boys; this does not, however, translate into long-term differences. Girls are also more likely than boys to offer praise, to agree with the person they’re talking to, and to elaborate on the other person’s comments; boys, in contrast, are more likely than girls to assert their opinion and offer criticisms (Leaper & Smith, 2004). In terms of temperament, boys are slightly less able to suppress inappropriate responses and slightly more likely to blurt things out than girls (Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, & Van Hulle, 2006).

With respect to aggression, boys exhibit higher rates of unprovoked physical aggression than girls, but no difference in provoked aggression (Hyde, 2005). Some of the biggest differences involve the play styles of children. Boys frequently play organized rough-and-tumble games in large groups, while girls often play less physical activities in much smaller groups (Maccoby, 1998). There are also differences in the rates of depression, with girls much more likely than boys to be depressed after puberty. After puberty, girls are also more likely to be unhappy with their bodies than boys.

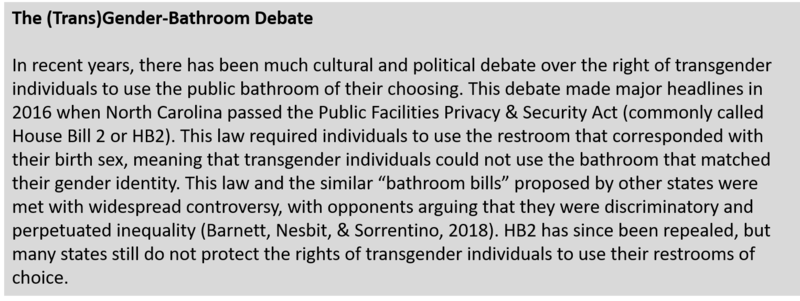

However, there is considerable variability between individual males and individual females. Also, even when there are mean level differences, the actual size of most of these differences is quite small. This means, knowing someone’s gender does not help much in predicting his or her actual traits. For example, in terms of activity level, boys are considered more active than girls. However, 42% of girls are more active than the average boy (but so are 50% of boys; see Figure 1 for a depiction of this phenomenon in a comparison of male and female self-esteem). Furthermore, many gender differences do not reflect innate differences, but instead reflect differences in specific experiences and socialization. For example, one presumed gender difference is that boys show better spatial abilities than girls. However, Tzuriel and Egozi (2010) gave girls the chance to practice their spatial skills (by imagining a line drawing was different shapes) and discovered that, with practice, this gender difference completely disappeared.

Many domains we assume differ across genders are really based on gender stereotypes and not actual differences. Based on large meta-analyses, the analyses of thousands of studies across more than one million people, research has shown: Girls are not more fearful, shy, or scared of new things than boys; boys are not more angry than girls and girls are not more emotional than boys; boys do not perform better at math than girls; and girls are not more talkative than boys (Hyde, 2005).

In the following sections, we’ll investigate gender roles, the part they play in creating these stereotypes, and how they can affect the development of real gender differences.

Gender Roles

As mentioned earlier, gender roles are well-established social constructions that may change from culture to culture and over time. In American culture, we commonly think of gender roles in terms of gender stereotypes, or the beliefs and expectations people hold about the typical characteristics, preferences, and behaviors of men and women.

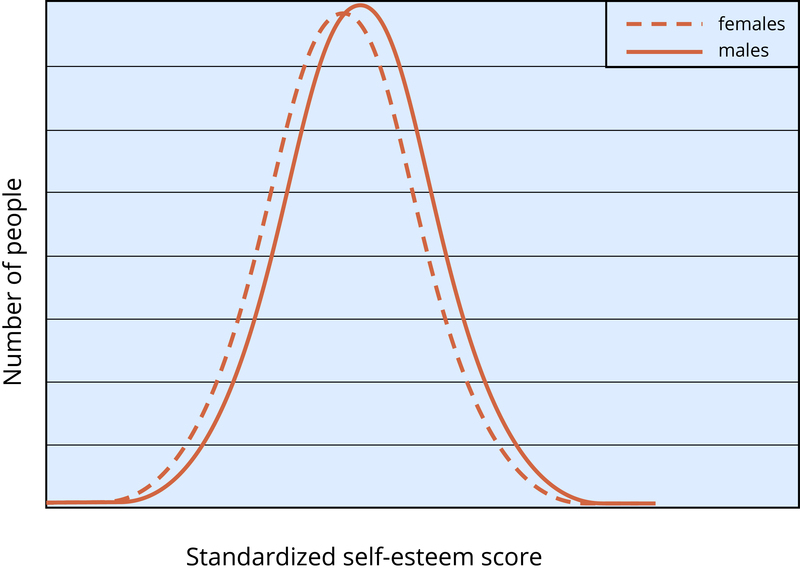

By the time we are adults, our gender roles are a stable part of our personalities, and we usually hold many gender stereotypes. When do children start to learn about gender? Very early. By their first birthday, children can distinguish faces by gender. By their second birthday, they can label others’ gender and even sort objects into gender-typed categories. By the third birthday, children can consistently identify their own gender (see Martin, Ruble, & Szkrybalo, 2002, for a review). At this age, children believe sex is determined by external attributes, not biological attributes. Between 3 and 6 years of age, children learn that gender is constant and can’t change simply by changing external attributes, having developed gender constancy. During this period, children also develop strong and rigid gender stereotypes. Stereotypes can refer to play (e.g., boys play with trucks, and girls play with dolls), traits (e.g., boys are strong, and girls like to cry), and occupations (e.g., men are doctors and women are nurses). These stereotypes stay rigid until children reach about age 8 or 9. Then they develop cognitive abilities that allow them to be more flexible in their thinking about others.

How do our gender roles and gender stereotypes develop and become so strong? Many of our gender stereotypes are so strong because we emphasize gender so much in culture (Bigler & Liben, 2007). For example, males and females are treated differently before they are even born. When someone learns of a new pregnancy, the first question asked is “Is it a boy or a girl?” Immediately upon hearing the answer, judgments are made about the child: Boys will be rough and like blue, while girls will be delicate and like pink. Developmental intergroup theory postulates that adults’ heavy focus on gender leads children to pay attention to gender as a key source of information about themselves and others, to seek out any possible gender differences, and to form rigid stereotypes based on gender that are subsequently difficult to change.

There are also psychological theories that partially explain how children form their own gender roles after they learn to differentiate based on gender. The first of these theories is gender schema theory. Gender schema theory argues that children are active learners who essentially socialize themselves. In this case, children actively organize others’ behavior, activities, and attributes into gender categories, which are known as schemas. These schemas then affect what children notice and remember later. People of all ages are more likely to remember schema-consistent behaviors and attributes than schema-inconsistent behaviors and attributes. So, people are more likely to remember men, and forget women, who are firefighters. They also misremember schema-inconsistent information. If research participants are shown pictures of someone standing at the stove, they are more likely to remember the person to be cooking if depicted as a woman, and the person to be repairing the stove if depicted as a man. By only remembering schema-consistent information, gender schemas strengthen more and more over time.

A second theory that attempts to explain the formation of gender roles in children is social learning theory. Social learning theory argues that gender roles are learned through reinforcement, punishment, and modeling. Children are rewarded and reinforced for behaving in concordance with gender roles and punished for breaking gender roles. In addition, social learning theory argues that children learn many of their gender roles by modeling the behavior of adults and older children and, in doing so, develop ideas about what behaviors are appropriate for each gender. Social learning theory has less support than gender schema theory—research shows that parents do reinforce gender-appropriate play, but for the most part treat their male and female children similarly (Lytton & Romney, 1991).

Gender Sexism and Socialization

Treating boys and girls, and men and women, differently is both a consequence of gender differences and a cause of gender differences. Differential treatment on the basis of gender is also referred to gender discrimination and is an inevitable consequence of gender stereotypes. When it is based on unwanted treatment related to sexual behaviors or appearance, it is called sexual harassment. By the time boys and girls reach the end of high school, most have experienced some form of sexual harassment, most commonly in the form of unwanted touching or comments, being the target of jokes, having their body parts rated, or being called names related to sexual orientation.

Different treatment by gender begins with parents. A meta-analysis of research from the United States and Canada found that parents most frequently treated sons and daughters differently by encouraging gender-stereotypical activities (Lytton & Romney, 1991). Fathers, more than mothers, are particularly likely to encourage gender-stereotypical play, especially in sons. Parents also talk to their children differently based on stereotypes. For example, parents talk about numbers and counting twice as often with sons than daughters (Chang, Sandhofer, & Brown, 2011) and talk to sons in more detail about science than with daughters. Parents are also much more likely to discuss emotions with their daughters than their sons.

Children do a large degree of socializing themselves. By age 3, children play in gender-segregated play groups and expect a high degree of conformity. Children who are perceived as gender atypical (i.e., do not conform to gender stereotypes) are more likely to be bullied and rejected than their more gender-conforming peers.

Gender stereotypes typically maintain gender inequalities in society. The concept of ambivalent sexism recognizes the complex nature of gender attitudes, in which women are often associated with positive and negative qualities (Glick & Fiske, 2001). It has two components. First, hostile sexism refers to the negative attitudes of women as inferior and incompetent relative to men. Second, benevolent sexism refers to the perception that women need to be protected, supported, and adored by men. There has been considerable empirical support for benevolent sexism, possibly because it is seen as more socially acceptable than hostile sexism. Gender stereotypes are found not just in American culture. Across cultures, males tend to be associated with stronger and more active characteristics than females (Best, 2001).

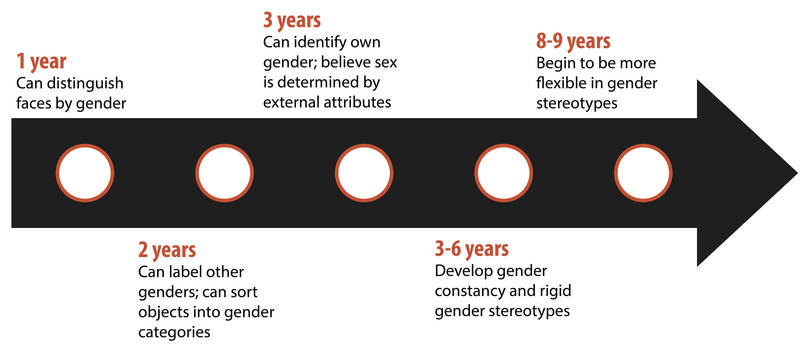

In recent years, gender and related concepts have become a common focus of social change and social debate. Many societies, including American society, have seen a rapid change in perceptions of gender roles, media portrayals of gender, and legal trends relating to gender. For example, there has been an increase in children’s toys attempting to cater to both genders (such as Legos marketed to girls), rather than catering to traditional stereotypes. Nationwide, the drastic surge in acceptance of homosexuality and gender questioning has resulted in a rapid push for legal change to keep up with social change. Laws such as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), both of which were enacted in the 1990s, have met severe resistance on the grounds of being discriminatory toward sexual minority groups and have been accused of unconstitutionality less than 20 years after their implementation. Change in perceptions of gender is also evident in social issues such as sexual harassment, a term that only entered the mainstream mindset in the 1991 Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill scandal. As society’s gender roles and gender restrictions continue to fluctuate, the legal system and the structure of American society will continue to change and adjust.