15

Charles Stangor

This chapter is from:

Charles Stangor’s Principles of Social Psychology. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/socialpsychology/chapter/3-1-moods-and-emotions-in-our-social-lives/

Introduction

Although affect can be harmful if it is unregulated or unchecked, our moods and emotions normally help us function efficiently and in a way that increases our chances of survival (Bless, Bohner, Schwarz, & Strack, 1990; Schwarz et al., 1991). The experience of disgust helps us stay healthy by helping us avoid situations that are likely to carry disease (Oaten, Stevenson, & Case, 2009), and the experience of embarrassment helps us respond appropriately to situations in which we may have violated social norms.

Affect signals either that things are going OK (e.g., because we are in a good mood or are experiencing joy or serenity) or that things are not going so well (we are in a bad mood, anxious, upset, or angry). When we are happy, we may seek out and socialize with others; when we are angry, we may attack; and when we are fearful, we are more likely to turn to safety. In short, our emotions help us to determine whether our interactions with others are appropriate, to predict how others are going to respond to us, and to regulate our behavior toward others.

The Physiology of Affect

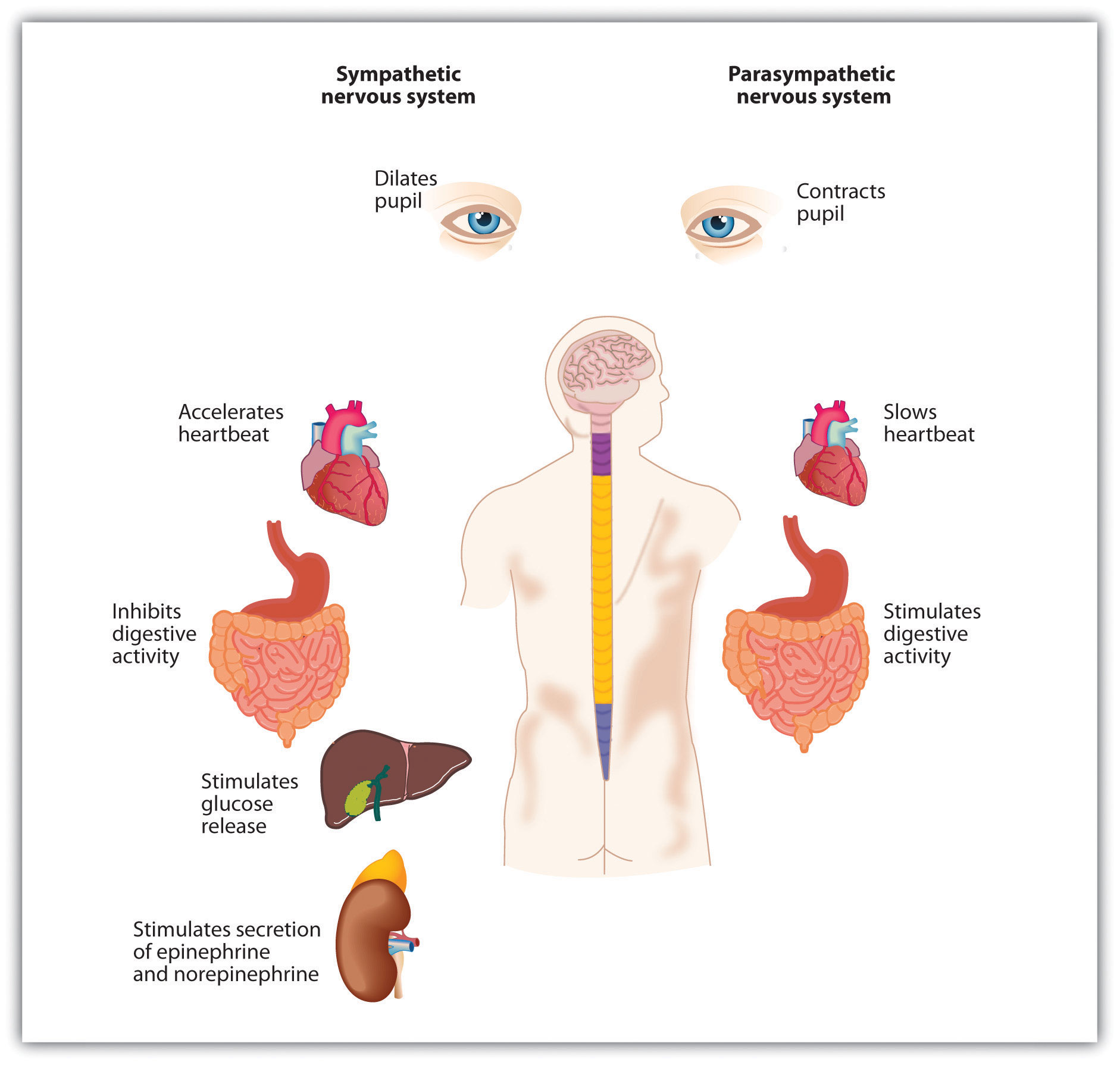

Our emotions are determined in part by responses of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS)—the division of the autonomic nervous system that is involved in preparing the body to respond to threats by activating the organs and the glands in the endocrine system. The SNS works in opposition to the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), the division of the autonomic nervous system that is involved in resting, digesting, relaxing, and recovering. When it is activated, the SNS provides us with energy to respond to our environment. The liver puts extra sugar into the bloodstream, the heart pumps more blood, our pupils dilate to help us see better, respiration increases, and we begin to perspire to cool the body. The sympathetic nervous system also acts to release stress hormones including epinephrine and norepinephrine. At the same time, the action of the PNS is decreased.

We experience the activation of the SNS as arousal—changes in bodily sensations, including increased blood pressure, heart rate, perspiration, and respiration. Arousal is the feeling that accompanies strong emotions. I’m sure you can remember a time when you were in love, angry, afraid, or very sad and experienced the arousal that accompanied the emotion. Perhaps you remember feeling flushed, feeling your heart pounding, feeling sick to your stomach, or having trouble breathing.

The arousal that we experience as part of our emotional experience is caused by the activation of the sympathetic nervous system. [Image from: Charles Stangor’s Principles of Social Psychology. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/socialpsychology/chapter/3-1-moods-and-emotions-in-our-social-lives/ CC BY-NC-SA http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/]

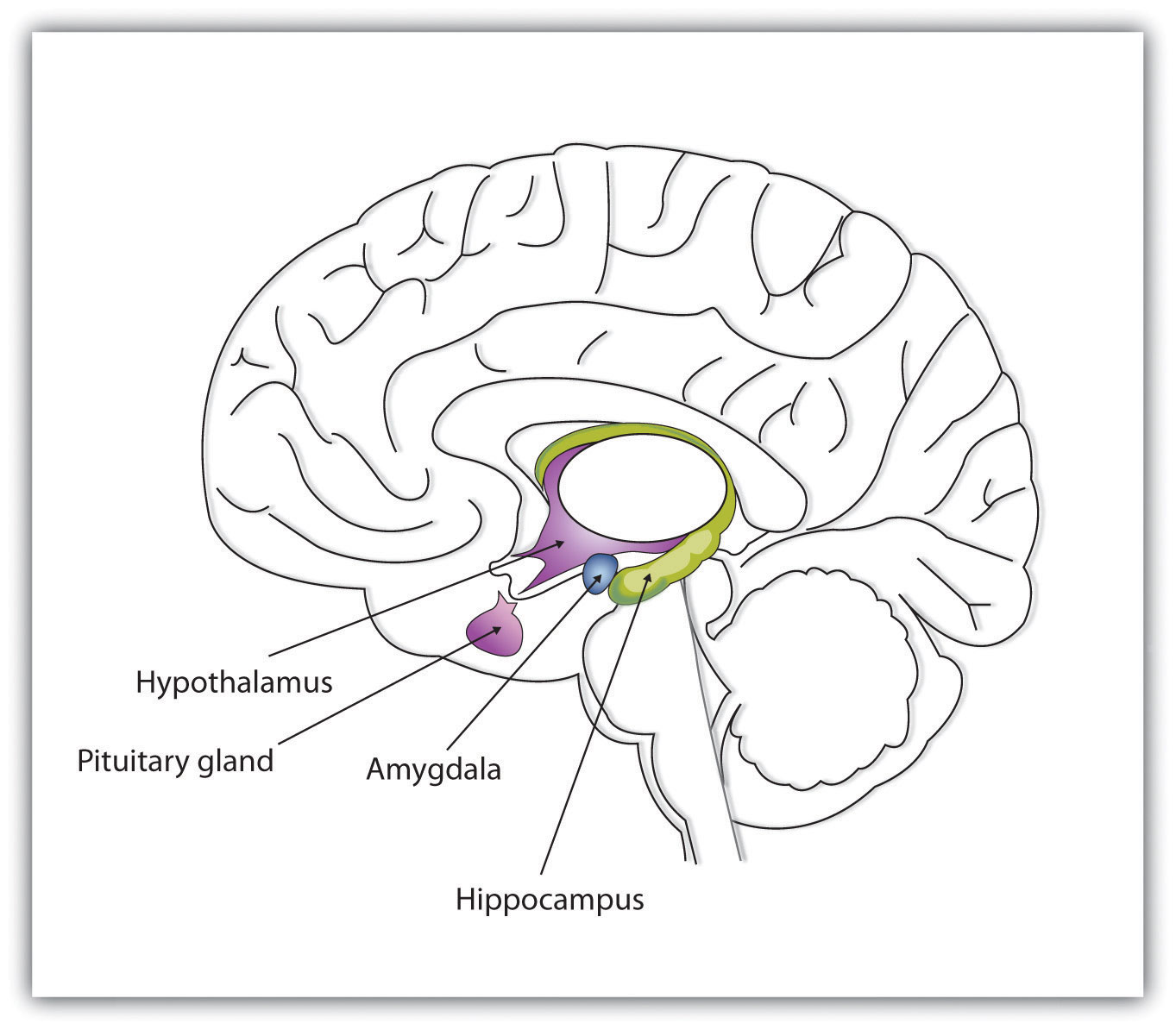

The experience of emotion is also controlled in part by one of the evolutionarily oldest parts of our brain—the part known as the limbic system—which includes several brain structures that help us experience emotion. Particularly important is the amygdala, the region in the limbic system that is primarily responsible for regulating our perceptions of, and reactions to, aggression and fear. The amygdala has connections to other bodily systems related to emotions, including the facial muscles, which perceive and express emotions, and it also regulates the release of neurotransmitters related to stress and aggression (Best, 2009). When we experience events that are dangerous, the amygdala stimulates the brain to remember the details of the situation so that we learn to avoid it in the future (Sigurdsson, Doyère, Cain, & LeDoux, 2007; Whalen et al., 2001).

The limbic system is a part of the brain that includes the amygdala. The amygdala is an important regulator of emotions. [Image from: Charles Stangor’s Principles of Social Psychology. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/socialpsychology/chapter/3-1-moods-and-emotions-in-our-social-lives/ CC BY-NC-SA http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/]

Basic and Secondary Emotions

The basic emotions (anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise) are emotions that are based primarily on the arousal produced by the SNS and that do not require much cognitive processing. These emotions happen quickly, without the need for a lot of thought or interpretation. Imagine, for instance, your fearful reaction to the sight of a car unexpectedly pulling out in front of you while you are driving, or your happiness in unexpectedly learning that you won an important prize. You immediately experience arousal, and in the case of negative emotions, the arousal may signal that quick action is needed.

Paul Ekman and his colleagues (Ekman, 1992; 2003) studied the expression and interpretation of the basic emotions in a variety of cultures, including those that had had almost no outside contact (such as Papua New Guinea). In his research, he showed people stimuli that would create a given emotion (such as a dead pig on the ground to create disgust) and videotaped the people as they expressed the emotion they would feel in that circumstance.

Ekman then asked people in other cultures to identify the emotions from the videotapes. He found that the basic emotions were cross-cultural in the sense that they are expressed and experienced consistently across many different cultures. A recent meta-analysis examined the perception of the basic emotions in 162 samples, with pictures and raters from many countries, including New Guinea, Malaysia, Germany, and Ethiopia. The analysis found that in only 3% of these samples was even a single basic emotion recognized at rates below chance (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002).

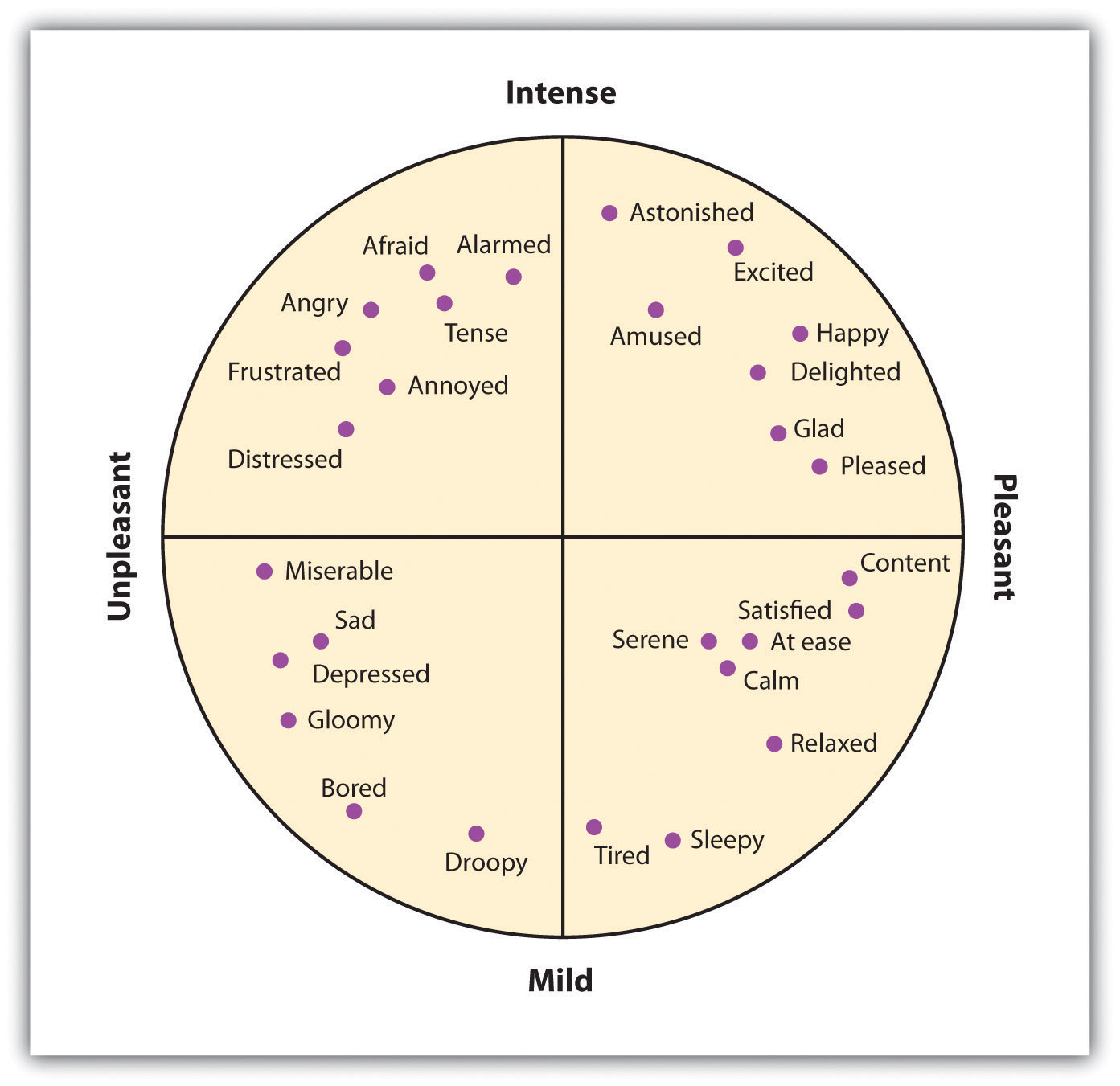

Figure 3.1

The secondary emotions are derived from the basic emotions but are more cognitive in orientation (Russell, 1980). [Image from: Charles Stangor’s Principles of Social Psychology. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/socialpsychology/chapter/3-1-moods-and-emotions-in-our-social-lives/ CC BY-NC-SA http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/]

In comparison to the basic emotions, other emotions, such as guilt, shame, and embarrassment, are accompanied by relatively lower levels of arousal and relatively higher levels of cognitive activity. When a close friend of yours wins a prize that you thought you had deserved, you might well feel depressed, angry, resentful, and ashamed. You might mull over the event for weeks or even months, experiencing these negative emotions each time you think about it (Martin & Tesser, 1996). In this case, although there is at least some arousal, your emotions are more highly determined by your persistent, and negative, thoughts. As you can see in Figure 3.1, there are a large number of these secondary emotions—emotions that provide us with more complex feelings about our social worlds and that are more cognitively based.

Cultural and Gender Differences in Emotional Responses

Although there are many similarities across cultures in how we experience emotions, there are also some differences (Marsh, Elfenbein, & Ambady, 2003). In Japan, there is a tendency to hide emotions in public, which makes them harder for others to perceive (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 1994). And as we would expect on the basis of cultural differences between individualism and collectivism, emotions are more focused on other-concern in Eastern cultures, such as Japan and Turkey, but relatively more focused on self-concern in Western cultures (Kitayama, Mesquita, & Karasawa, 2006; Uchida, Kitayama, Mesquita, Reyes, & Morling, 2008). Ishii, Reyes, and Kitayama (2003) found that Japanese students paid more attention to the emotional tone of voice of other speakers than did American students, suggesting that the Japanese students were particularly interested in determining the emotions of others. Self-enhancing emotions such as pride and anger are more culturally appropriate emotions to express in Western cultures, whereas other-oriented emotions such as friendliness and shame are seen as more culturally appropriate in Eastern cultures. Similarly, Easterners experience more positive emotions when they are with others, whereas Westerners are more likely to experience positive emotions when they are alone and as a result of their personal accomplishments (Kitayama, Karasawa, & Mesquita, 2004; Masuda & Kitayama, 2004).

There are also gender differences in emotional experiences. Women report that they are more open to feelings overall (Costa, Terracciano, & McCrae, 2001), are more likely to express their emotions in public (Kring & Gordon, 1998), and are more accurate and articulate in reporting the feelings of others (Barrett, Lane, Sechrest, & Schwartz, 2000). These differences show up particularly in terms of emotions that involve social relationships. Kring and Gordon (1998) had male and female students watch film clips that portrayed sadness, happiness, or fear and found that the women reacted more visibly to each film. Coats and Feldman (1996) found that it is easier to read the emotions that women express. Some of these observed gender differences in emotional experiences and expression are biological in orientation, but they are also socialized through experience.

Moods Provide Information About Our Social Worlds

One function of mood is to help us determine how we should evaluate our current situation. Positive moods will likely lead us to maintain our current activities, which seem to be successful, whereas negative moods suggest that we may wish to attempt to change things to improve our situation. And moods have other influences on our cognition and behavior: Positive moods may lead us to think more creatively and to be more flexible in how we respond to opinions that are inconsistent with cultural norms (Ashton-James, Maddux, Galinsky, & Chartrand, 2009). Ito, Chiao, Devine, Lorig, and Cacioppo (2006) found that people who were smiling were also less prejudiced.

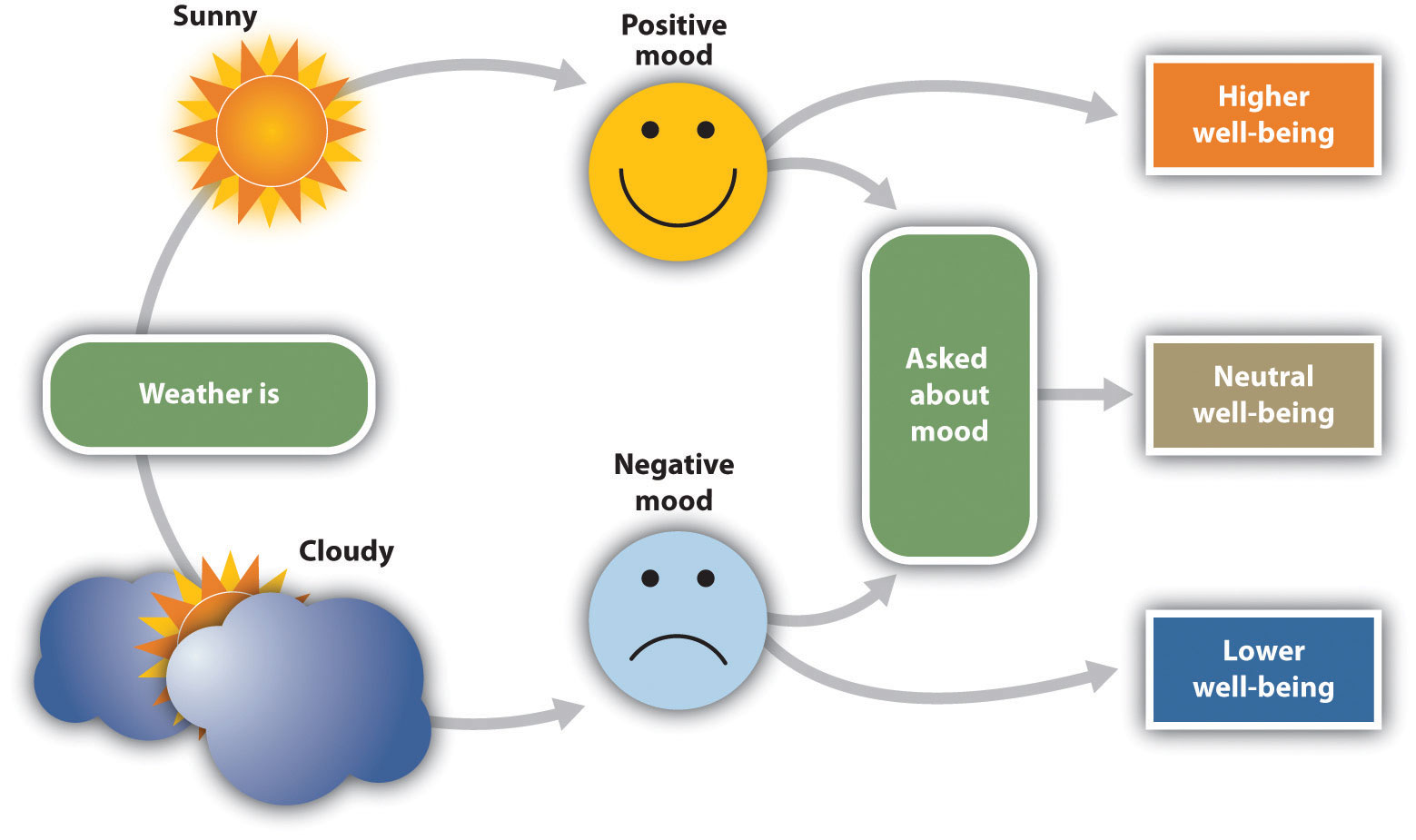

Mood states are also powerful determinants of our current well-being. To study how people use mood states as information to help them determine their current well-being, Norbert Schwarz and Gerald Clore (1983) called participants on the telephone, pretending that they were researchers from a different city conducting a survey. Furthermore, they varied the day on which they made the calls, such that some of the participants were interviewed on sunny days and some were interviewed on rainy days. During the course of the interview, the participants were asked to report on their current mood states and also on their general well-being. Schwarz and Clore found that the participants reported better moods and greater well-being on sunny days than they did on rainy days.

Schwarz and Clore wondered whether people were using their current mood (“I feel good today”) to determine how they felt about their life overall. To test this idea, they simply asked half of their respondents about the local weather conditions at the beginning of the interview. The idea was to subtly focus these participants on the fact that the weather might be influencing their mood states. And they found that as soon as they did this, although mood states were still influenced by the weather, the weather no longer influenced perceptions of well-being (Figure 3.2 “Mood as Information”). When the participants were aware that their moods might have been influenced by the weather, they realized that the moods were not informative about their overall well-being, and so they no longer used this information. Similar effects have been found for mood that is induced by music or other sources (Keltner, Locke, & Audrain, 1993; Savitsky, Medvec, Charlton, & Gilovich, 1998).

Figure 3.2 Mood as Information

The current weather influences people’s judgments of their well being, but only when they are not aware that it might be doing so. After Schwarz and Clore (1983). [Image from: Charles Stangor’s Principles of Social Psychology. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/socialpsychology/chapter/3-1-moods-and-emotions-in-our-social-lives/ CC BY-NC-SA http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/]

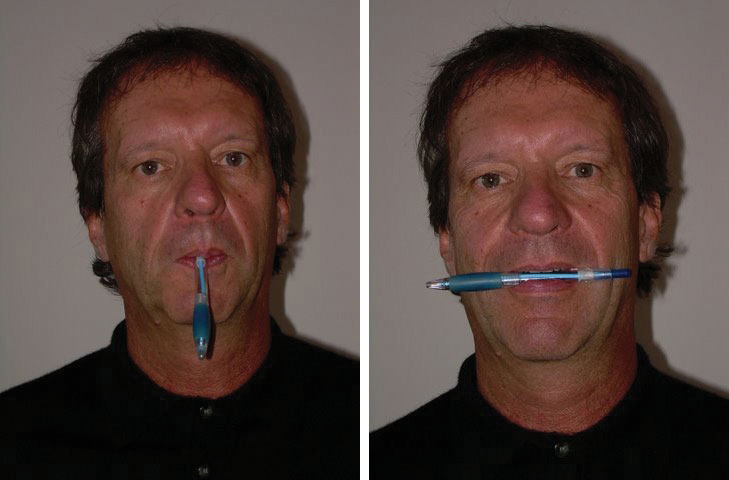

Even moods that are created very subtly can have effects on perceptions. Fritz Strack and his colleagues (Strack, Martin, & Stepper, 1988) had participants rate how funny cartoons were while holding a writing pen in their mouth such that it forced them either to use muscles that are associated with smiling or to use muscles that are associated with frowning (Figure 3.3). They found that participants rated the cartoons as funnier when the pen created muscle contractions that are normally used for smiling rather than frowning. And Stepper and Strack (1993) found that people interpreted events more positively when they were sitting in an upright position rather than a slumped position. Even finding a coin in a pay phone or being offered some milk and cookies is enough to put people in good moods and to make them rate their surroundings more positively (Clark & Isen, 1982; Isen & Levin, 1972; Isen, Shalker, Clark, & Karp, 1978).

Figure 3.3

The position of our mouth muscles can influence our mood states (Strack, Martin, & Stepper, 1988).[Image from: Charles Stangor’s Principles of Social Psychology. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/socialpsychology/chapter/3-1-moods-and-emotions-in-our-social-lives/ CC BY-NC-SA http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/]

These results show that our body positions, especially our facial expressions, influence our affect. We may smile because we are happy, but we are also happy because we are smiling. And we may stand up straight because we are feeling proud, but we also feel proud because we are standing up straight (Stepper, & Strack, 1993).

Misattributing Arousal

Although arousal is necessary for emotion, it is not sufficient. Arousal becomes emotion only when it is accompanied by a label or by an explanation for the arousal (Schachter & Singer, 1962). Thus, although emotions are usually considered to be affective in nature, they really represent an excellent example of the joint influence of affect and cognition. We can say, then, that emotions have two factors—an arousal factor and a cognitive factor (James, 1890; Schachter & Singer, 1962).

Emotion = arousal + cognition

In some cases, it may be difficult for people who are experiencing a high level of arousal to accurately determine which emotion they are experiencing. That is, they may be certain that they are feeling arousal, but the meaning of the arousal (the cognitive factor) may be less clear. Some romantic relationships, for instance, are characterized by high levels of arousal, and the partners alternately experience extreme highs and lows in the relationship. One day they are madly in love with each other, and the next they are having a huge fight. In situations that are accompanied by high arousal, people may be unsure what emotion they are experiencing. In the high-arousal relationship, for instance, the partners may be uncertain whether the emotion they are feeling is love, hate, or both at the same time. Misattribution of arousal occurs when people incorrectly label the source of the arousal that they are experiencing.

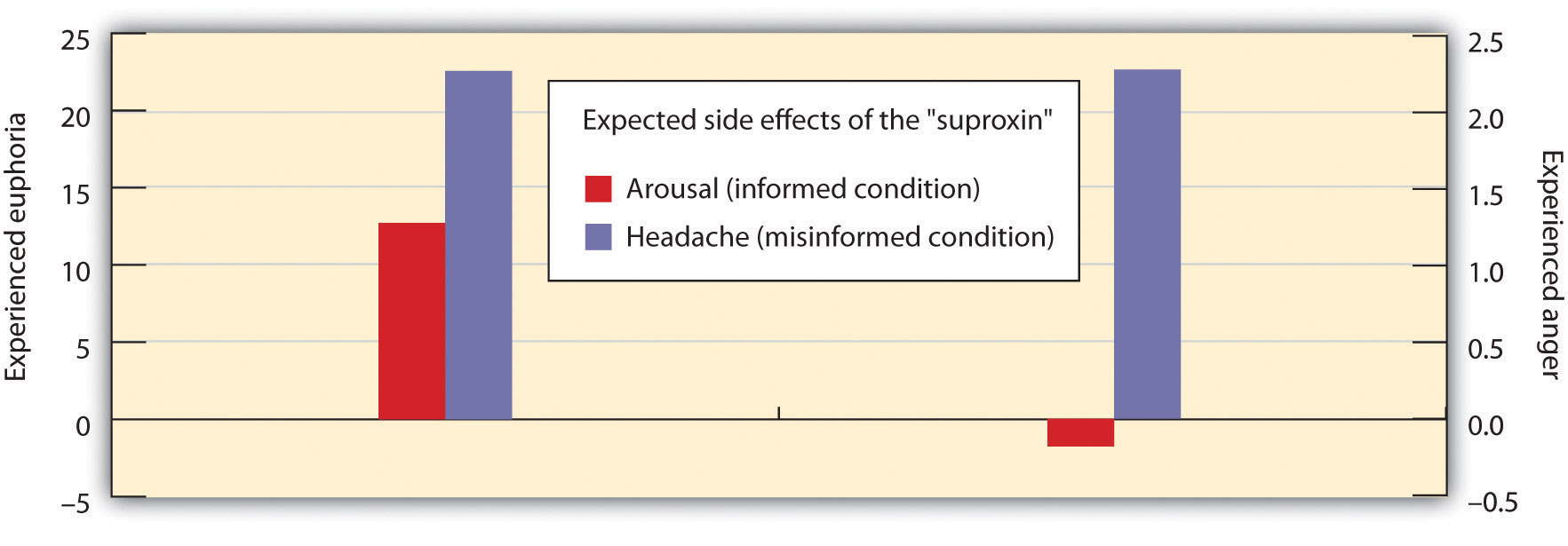

Figure 3.4 Misattributing Emotion

The results of an experiment by Schachter and Singer (1962) supported the two-factor theory of emotion. The participants who did not have a clear label for their arousal were more likely to take on the emotion of the confederate. [Image from: Charles Stangor’s Principles of Social Psychology. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/socialpsychology/chapter/3-1-moods-and-emotions-in-our-social-lives/ CC BY-NC-SA http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/]