1

Brianna Buljung

This chapter will help you:

- Conceptualize your research prior to beginning a project

- Plan the logistics of your research project

- Determine how to find a place for your research interests in your discipline

Introduction

Searching or beginning to locate information is not the first step in any research project; instead projects should begin with careful planning and reflection. Establishing a plan and norms for the project will help you to be more efficient and effective throughout the entire lifecycle of the project. This planning includes situating the research within the discipline, establishing a plan for organizing the research materials and considering the keywords and search parameters that will initially be used.

This chapter will help you to plan your research by conceptualizing your research and consider the logistics of the project. It will explore both the theoretical aspects of the project, especially in selecting a topic, and the practical aspects of being an efficient researcher. It will use the topic of aquatic invasive species as an example throughout. As you work through the chapter, consider your own discipline and pending research projects; reflect on how the various topics discussed might be applicable to your situation.

Why Planning is Important

Few researchers have the luxury of working on a single project or devoting all of their time to research. Most, especially those in academia, are also balancing other obligations such as teaching, service, advising and personal responsibilities. Because research is typically only a portion of your responsibilities, it is important to use the time available well. What does it mean to an effective researcher? This type of researcher is productive, knowing which tools and sources are the best for their work. They also know where to seek help if they cannot find resources or use needed tools. These researchers are also efficient, making good use of available tools, resources and time to accomplish tasks. Finally, they effectively communicate to make a meaningful contribution to their discipline. Most researchers have projects that fail for one reason or another, but effective researchers are able to avoid the issues of endless searching or research inertia.

One of the most effective practices you can adopt as a researcher is building time for reflection into the process throughout the project. Research is iterative, new questions and avenues for exploration arise from the acquisition of knowledge. You may find that you revisit different aspects throughout the project as your understanding of the topic grows. The research workflow can also be iterative and develop over time, especially for early career researchers. It may take time for you to develop the habits of an effective researcher or to determine which tools and processes work best for you and your research team. Some early career researchers gain experience while working as part of an established research group, but others must learn by beginning projects on their own. Each chapter in this text will provide questions or a brief activity that can help you reflect on how that aspect or tool applies to your project. Making time for reflection ensures your processes and norms are working properly and that the project is meeting your goals.

One of the most significant issues facing early career researchers is finding a meaningful way to contribute to and impact their discipline. It can be daunting to enter the scholarly conversation or to feel like your work is worthy of publication. Although it can take time, it is possible to find your place in the research of your discipline. Start by reading both widely and deeply. Read widely to become comfortable with the breadth of research in your broad areas of interest. This technique will help you to learn terminology, publishing practices, top journals and methodological approaches. Then, read deeply in areas of particular interest. These are the types of articles you would cite in your work, the authors you follow or would seek out as collaborators. You can use these articles to find gaps in the literature that you can explore. Within each article, focus on the literature review to learn more about how their research fits into the larger conversation. Then, look to the conclusions or research limitations section to identify gaps or further work that you could pursue. You may also find potential collaborators who are interested in pursuing the same lines of inquiry.

Additionally, do not feel like you must learn techniques and tools all on your own. Seek out a mentor either in your discipline or in an adjacent one. Find a scholar who is doing the type of work that you would like to do so that you can learn from their successes and struggles. Take advantage of opportunities to ask questions and learn from others. Ask scholars about their research, why they selected particular methodologies or pursued different areas of research.

How to Prepare for Research

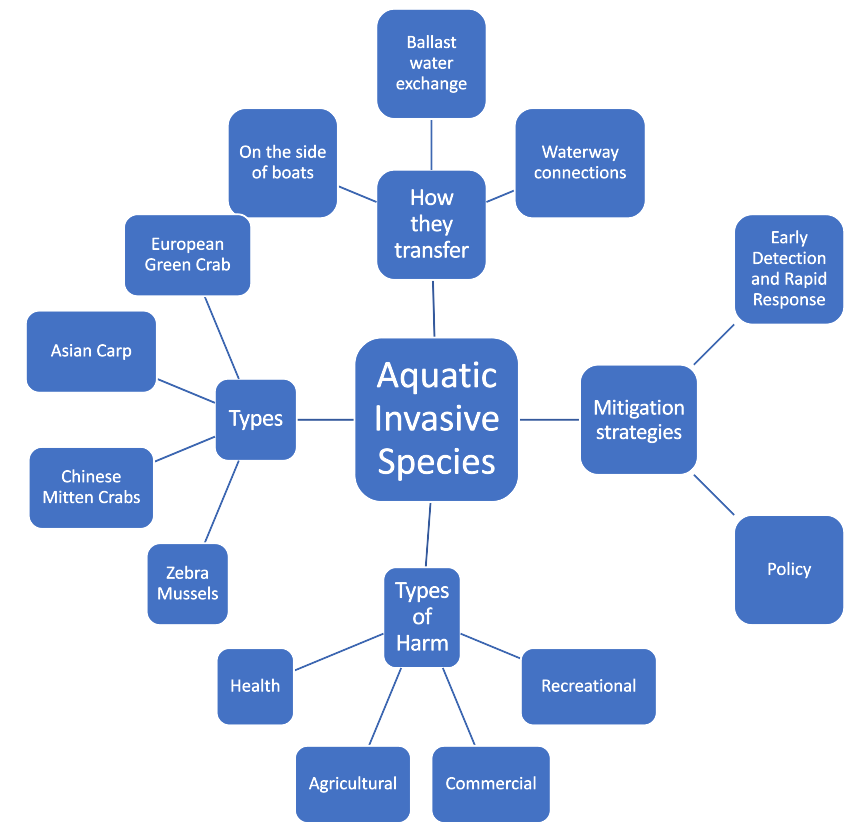

Concept mapping or mind mapping can be an effective way to conceptually organize your research ideas and find an appropriate scope for your project topic. A concept map helps you to visually organize a topic, beginning with broad concepts in the center, then narrowing and focusing as the concepts move out from the center. The map creates connections between different elements of the topic, especially relationships between broader and narrower elements. Below is a concept map for a project related to aquatic invasive species. From the center of the map, four narrower topics connect to details about that specific aspect. The map could continue to become more detailed if additional, narrower details were added to the third level concepts.

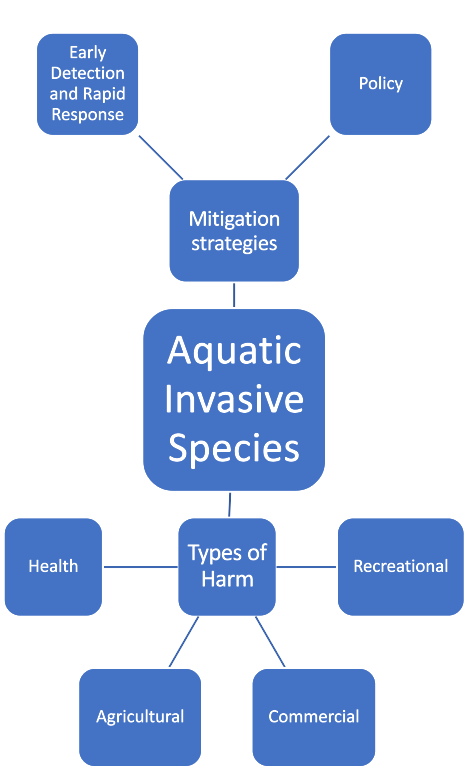

Once you have completed a large concept map, you can use it to narrow your topic into a focused research question. There are different ways to narrow the research based on the concept map. You can take one of the branches of your concept map and continue refining by adding details and additional branches. You can also take the larger topic and apply a particular technology or methodological approach to it. For example, you could select a particular mitigation strategy to address problems caused by one particular type of species, such as zebra mussels. Finally, you could situate your topic in a particular location or setting. You may be able to apply lessons learned and strategies developed in other research in your discipline to a specific case study, for example lakes in Colorado, USA. The concept map below takes two branches of the larger topic and investigates them in more detail.

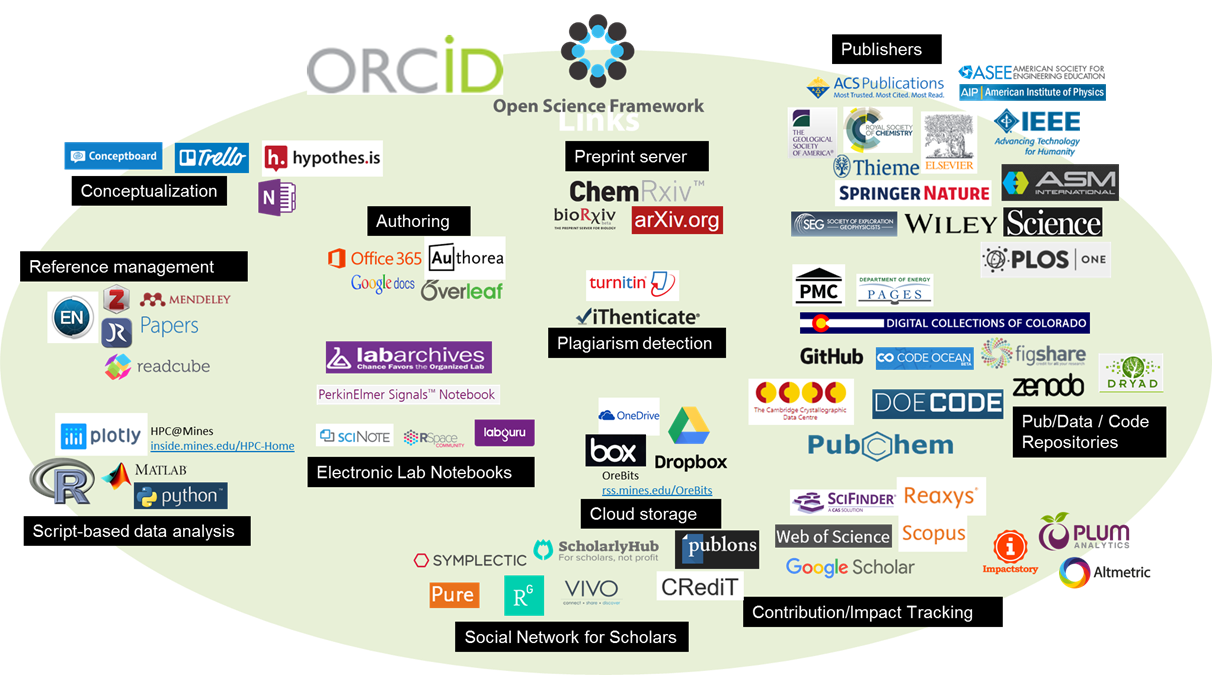

After you have begun to conceptualize your topic and focus on a research question, it can be helpful to organize the logistics of the research project. This initial organization will most likely adapt as you work through the project and this book. Each of the following chapters in the book will help you to consider a different aspect of the project. Your planning notes will become more refined as you learn more in each chapter. This initial organization can help you broadly consider the types of tools and platforms that will be most useful for this particular project. As the graphic below depicts, the research ecosystem is vast and there are many different tools that can be used at each stage of the research lifecycle.

In the initial stages of a project you do not necessarily have to decide on the granular aspects of the project, such as which journals you would like to publish in or how the data will be coded. However, establishing some basic organizational norms can be helpful, especially if you are working in a team or as part of a larger project. Determine how you will organize and share notes with collaborators. Some teams use a tool like an electronic lab notebook to store time-stamped notes from all aspects of the project, while others use a shared document or file. Another decision that it can be helpful to make early in the process is how files will be stored and how citations will be managed. Chapter 4 discusses citation management in more depth.

Ensuring the tools and processes used align with your research workflow is the most important element of project organization. You have to be able to consistently follow the norms you have established, otherwise you are wasting effort. If you do not typically take detailed notes you might struggle to adjust to that practice. Or, if you are unaccustomed to consistently naming documents, adopting a standard file naming convention can help to organize your work.

The last step prior to beginning research is to take time to consider your search strategies, locations and terminology. While you may feel comfortable with your topic and disciplinary databases, brief moments of reflection throughout the search process will help you become a more efficient and effective searcher.

First, take some time to brainstorm different elements of your search strategy. Even if you are very comfortable with your topic, start by making a list of the terms you will use in your searches. These terms should include discipline or industry specific terms, common language terms, acronyms, commonly accepted brand or entity names, specific locations and other associated terms as appropriate for your discipline. Some search topics might rely heavily on geographic terms or acronyms while others may not. After you have considered terms, establish a broad time frame for your search results. This will heavily depend on the discipline and purpose of the project. Topics that are focused on emerging technologies will have a shorter, more contemporary time frame than research in the earth sciences or history might. It is helpful to keep a copy of these notes nearby while searching. Then you can modify and reevaluate as needed.

The concept map we created to explore and refine our topic will be very useful when making a list of potential search terms. As the table below depicts, several terms are taken directly from the map. The list is then enhanced with additional terms that will be of use to our search.

|

Term Type |

Examples |

|

Discipline specific terms |

Aquatic invasive species, exotic, invasive, non-indigenous or non-native |

|

Common language terms |

Zebra mussel, European Green Crab |

|

Acronyms |

AIS (aquatic invasive species) |

|

Brand or Entity Names |

Fish and Wildlife, Nature Conservancy |

|

Location |

Colorado lakes, Great Lakes, Nile River |

|

Associated terms |

Unintentional introduction, ballast water, ethics, impact, harm |

Get into the habit of taking notes and documenting your research project. Use concept mapping to explore your topic and generate keywords. Return to your notes throughout the project as you learn additional information from your sources. Documenting your research project can help you to stay organized, communicate with your collaborators and eventually write about the research.

Tips for Starting Your Research Project

- One of the best ways to find a place for your research in your discipline is to read the other research in your field. Find articles with a similar approach to your work or a similar focus.

- Take the time to plan the logistics of your project. Determining how notes will be stored, how citations will be managed, which word processing tool will be used can save time and effort throughout the project, especially if you are working collaboratively.

- Use reflection tools like concept mapping to conceptualize your topic and the project scope. You will be identifying potential keywords while narrowing and focusing the topic.

- To narrow your research topic you can:

- Take one of the branches of your concept map and continue refining

- Situate your topic in a particular location or setting

- Consider a particular technology or methodological approach to the topic

Reflection

Now that you have a better understanding of how to plan your project to improve efficiency and stay organized, consider the following in relation to a project of your choosing:

- Consider the scope of your project and how it fits into your discipline. If your work is interdisciplinary, consider where your topic will intersect with both disciplines.

- Make an initial plan for the logistics of your project – you will be able to revisit and refuse this in later chapters. Consider how you will manage the project and where you will store citations and files.

- Brainstorm keywords related to your topic – don’t forget to consider all kinds of terms, such as common language terms, technical terms, acronyms, geography and related words.

- Brainstorm the other elements you will need to be an effective searcher, including time frame, types of information needed and potential sources of that information.