2

Brianna Buljung

This Chapter will help you:

- Practice using appropriate search techniques for your research needs

- Identify types of information needed and where those sources are located

- Consider how to evaluate sources for inclusion in your project

Introduction

In our digital world, searching for research sources might seem as easy as dropping a few words into an internet search engine. However, effectively searching for, finding and evaluating sources for your work can be more complicated.

The process of searching for information depends heavily on the project and specific needs of the researcher. Those needs will dictate where you search, the types of documents and sources needed and how they will be used in the project. This chapter will use the example topic of water storage in Taiwan to consider keywords, potential databases and collections to use and how to evaluate sources. Consider a research topic of interest to you as you read the examples.

In this chapter, you will have the opportunity to practice searching for and evaluating information to include in your research. You will be encouraged to explore important considerations prior to starting your search including the types of sources that you may want to include and how to evaluate found items. As you work through the material, take the time to reflect on your own research habits and how these techniques could be incorporated into your work.

Why Effective Searching and Source Evaluation Matter

The type of sources that you use for your research have consequences. You must consider the types of information that you need for the project. Will you need to find data sets? Or perhaps just journal articles? Standards? Having a good understanding of the type of necessary sources will allow you to use format filters in databases to exclude information you do not need. Also, knowing more about necessary sources will help you to identify the parties creating and holding those types of sources. For example, if you need standards you will most likely want to go straight to a standards organization or database. Remember, your notes document will probably change and evolve throughout the life of the project as you learn more about the topic and pursue new questions.

Some general types of resources are broadly applicable across many disciplines and types of projects. The nuances of these sources vary depending on how much emphasis your discipline places on that type of resource. This table can help you consider what role these general sources might play in your project.

|

Type |

Use in Research |

Take Note |

|

Books |

Reference books, handbooks, and manuals provide background information. Books contain in depth discussion on a related topic |

Don’t read the entire book! Use the table of contents, introduction and index to find useful sections |

|

Journal Articles |

Articles detail the ongoing discussion surrounding a topic, use them to support your findings or get ideas for methods to try |

Most journals are located behind paywalls, contact your local library for assistance before purchasing articles |

|

Conference Papers |

Early results, works-in-progress and methodology papers can be helpful in gathering ideas and planning your project |

Conference papers are often the fastest route to publication for researchers, but they may not contain finalized data or complete projects. |

|

Newspapers and Magazines |

Often written by non-disciplinary experts, they provide perspective on the real world applications of your work |

News websites may contain paywalls and news stories in library databases may be missing infographics and images. |

|

Laws and Regulation |

They provide boundaries for what is feasible in research; ensure your project is safe and follows applicable government regulation |

Consider these sources early in the project, follow the most up to date regulatory guidance |

|

Industry (trade) publications |

Many professional associations produce news and reports that can give you ideas and help you to identify potential collaborators |

These sources can provide the latest information on trends in the industry |

|

Theses and Dissertations |

Use these to find methodologies that might be useful, they are typically well referenced and detailed |

The long bibliography can be helpful in identifying additional sources to use |

|

Data Sets |

Raw and/or aggregate data sets will be useful to validate your own results |

Data is increasingly available in repositories and government data sites. You might need to seek permission from the creators before use. |

Most academic writing will rely, at least in part, on scholarly, peer reviewed articles and conference papers. These sources are often considered the highest quality research sources available. They typically contain a few specific features:

- The author and their affiliation will almost always be listed

- They are based on research and typically include figures, graphs and tables

- Other research in the article is supported by citations

- Typically found in reputable journals or conference proceedings

- Vetted by other experts in the field through a peer review process

Expectations and standards for scholarly articles can vary a little depending on the discipline. Novice researchers can use tools like the Anatomy of a Scholarly Article from North Carolina State University Libraries to help identify scholarly sources.

While scholarly, peer reviewed journal articles are often considered the highest quality sources, there are biases and limitations inherent in the journal publishing system. Research has demonstrated that reviewer biases can play a role in accepting or rejecting articles, often leading to a negative impact on female and minority researchers. [1] [2] It is also not necessarily representative of the entire scholarly landscape or adequately inclusive of researchers from outside western countries. [3]

How to Find Sources

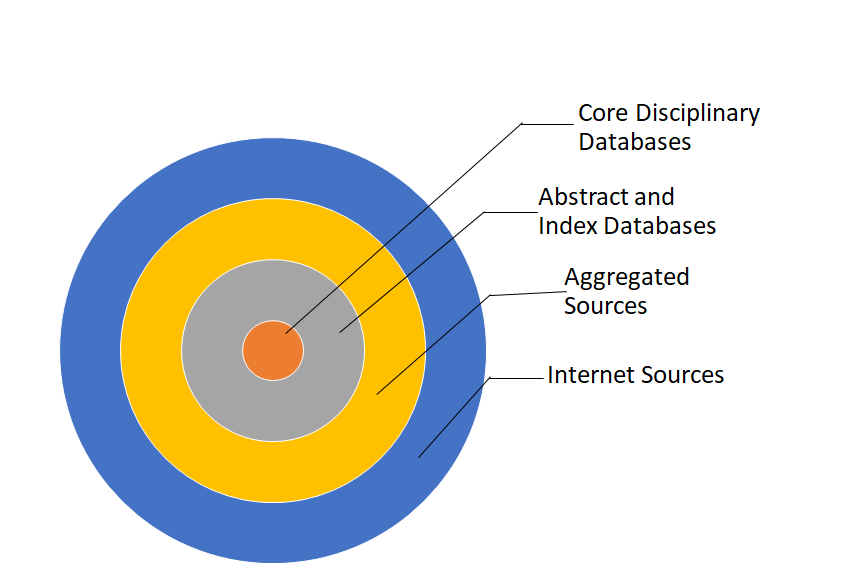

For early career researchers, a good place to start locating sources is the library and specific disciplinary databases. It can be helpful to think of research sources as a series of concentric circles in which the sources become more broad as they move out from the center. In the center of the circle are the most specialized sources, discipline specific databases. These tools are highly focused on specific subjects and types of sources. As you progress in your career, you will become comfortable identifying and using the databases in your specific discipline. Be sure that you understand the scope of the databases in your discipline as they may only collect certain types of sources or have a limited time frame covered. It can be easy to become frustrated if you are unable to find results in a database and commonly this issue is partially due to seeking sources beyond that collection’s focus.

The next larger circle includes abstracting and indexing databases. These tools, such as Scopus, Compendex and Web of Science, gather records for the literature in different disciplines into a single powerful tool. This type of database allows you to analyze the literature on a topic using citation counts, author searches and other types of specialty bibliometric analysis. The third circle includes aggregated sources such as Google Scholar or the library’s catalog. These collections allow you to search broadly across disciplines and document types. The results can often include false hits or irrelevant information, meaning that you may have to spend more time reviewing the results. The collections in this circle can be helpful for novice researchers and also for researchers completing interdisciplinary work. They will identify relevant sources from multiple disciplines. The biggest circle is the internet and all the other sorts of sources you may need to include in your project, such as patents, technical reports, websites, policy and codes. Many of these types of sources are not represented in academic databases and an internet search is the most efficient way to locate them.

The layout of library websites can vary depending on local and institutional needs and norms. However, most library sites share a few common features that every researcher should be aware of

|

Feature |

Description |

Take Note |

|

Catalog or collections search |

Search library physical collections, increasingly this search also includes results from databases |

Be sure you know what is included in this search, if you are struggling to find results, it might be too limited for your needs. |

|

List of Databases |

Links to databases that typically includes notes on scope and time frame covered |

Be sure you know what you might need to do to be able to search the databases from off campus. |

|

Research Help Contacts |

Specific librarians or a central contact for getting help |

Not all libraries have librarians on duty in the evening – don’t wait until the last minute to seek help |

|

Method to Request Materials |

Many libraries offer a service to request materials from other libraries. |

This service can take some time, don’t wait until the last minute to request materials |

It may not be possible for researchers to access university libraries and/or all disciplinary databases. However, it is still possible to find high quality academic research on the open web. Increasingly, academic research is being made available via open access collections as well as institutional and government repositories. Many countries and disciplines have open access repositories of full journal articles, data sets and preprints. One of the largest pre-prints collections is arXiv, which specializes in physics, computer science, mathematics, electrical engineering and other related disciplines. One of the largest open access journal repositories is Scientific Electronic Library Online or SciELO. SciELO focuses on journals from many countries across Latin America as well as South Africa.

Once you have begun to find sources that meet your information needs, you can use them to find other sources that may be of interest. It is good for researchers to get into the habit of moving both forward and backward from a single item. Whenever you find a useful source, such as a scholarly article, look at their bibliography or list of references for other items that may be of interest. You are using the source to move backwards in the conversation in the discipline. Then, using a disciplinary database or a tool like Web of Science or Google Scholar, look at the sources that have cited this particular paper. You are using the source to move forward in the scholarly conversation. This strategy can help you to find newer technologies, interpretations, and statistics related to your research topic. The citation tracing practice is commonly used with scholarly articles, but can be modified for other types of sources. Any time your source contains embedded links, suggestions for additional reading or references you should take the time to determine if any of those older sources will be of value to your project. Tracing the conversation forward can be more difficult with informally published materials as they may not be in a tool like Google Scholar. However, you can place standards, laws, protocols and other types of official documentation into a search to see all the different sources that have used them.

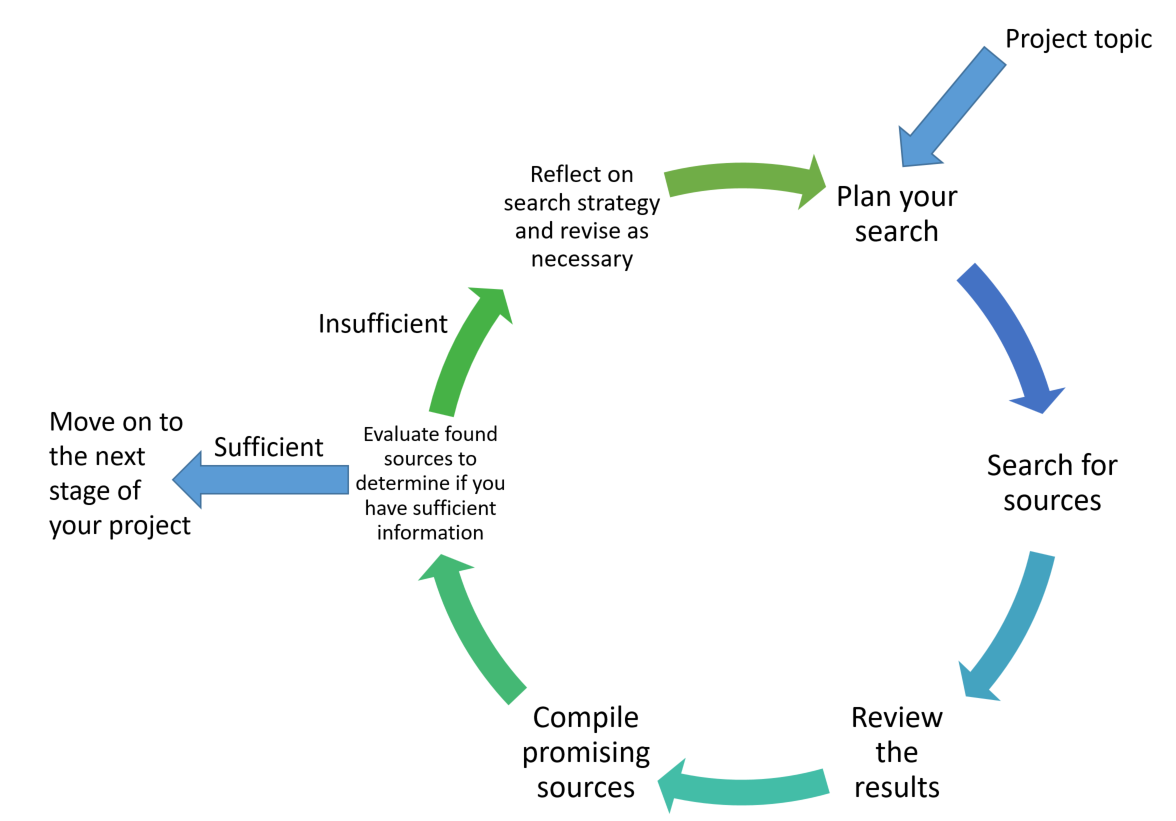

Few researchers find all their desired research materials in a single session of searching. Reviewing found sources will prompt new questions and lines of inquiry. Novice researchers can become overwhelmed by the amount of information available, especially when using broad tools like the library catalog and the internet. They can feel the need to keep searching endlessly. Eventually, you have to stop searching and begin the next steps in the project. If you find that you are afraid to stop searching for fear of missing something, you can set up alerts in your primary databases and Google Scholar to send you new results on your topic. This can help ensure you have the latest research on your topic area without becoming stuck in the search phase.

How to Evaluate Sources

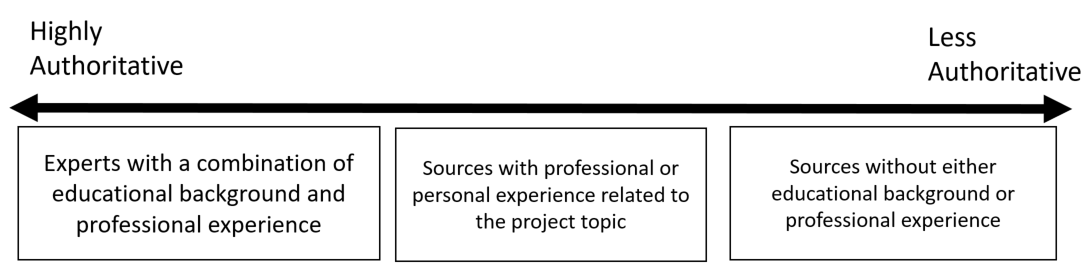

Evaluating sources goes beyond simply acknowledging a source’s biases. It is also more in depth than determining if a source is scholarly. Most academic research is based on sources that are scholarly and/or authoritative. All scholarly sources should be authoritative, written by an expert in the topic, who has a combination of academic and professional experience in a related discipline. Authoritative sources can also extend beyond these formally written journal articles, to include standards, protocols, government reports, data sets, interviews and more. When selecting and evaluating sources for your research, the most important consideration should always be your specific need and the purpose for which you intend to use the source. There are several questions to reflect on that can help you to determine the usefulness and accuracy of the source.

Who published the source and what is their authority on the topic? Answering this question can help you explore a source’s biases. You should consider both the author and publisher of the source. Does the author have academic background and/or professional experience in this topic area? A new story written by a staff journalist will have a different authority than a report written by an engineer with 20 years of experience.

What is the purpose of the source? Some sources are written in a largely unbiased manner to inform the public or academic research. Others are written for a young audience or to persuade the reader of a particular perspective. Once you have determined the purpose, you should also reflect on how your use of the source will mirror or differ from that intended purpose.

Is the information accurate and timely? Timeliness can vary depending on the discipline as some, such as geology, can rely on much older information than others, such as computer science. When answering this question, consider how well the source reflects the current understanding of the topic. Does the source portray an outdated, refuted or inaccurate view of the topic? Does the information align with current understanding and the other sources I’ve found so far?

How relevant is it for this specific project? This is the single most important question you can ask when evaluating sources. You should establish a clear understanding of how the item will fit into your project and to do that, consider different types of fit. For example, sources could be used to support your thesis, provide background information, serve as a counter-argument you refute or establish current understanding of the topic. The need will dictate the use of sources that might not typically be considered suitable, such as social media, industry sources, websites and personal interviews.

To demonstrate how these questions can apply to real world research projects, let’s return to our water storage in Taiwan topic. The Water Resources Agency, part of the Ministry of Economic Affairs, provides publications, policies, statistics and laws on their website. The statistics will be useful for a paper evaluating different approaches to water storage. The “About” page on the site can be used to determine author authority and potential biases of the information. The agency leads all government activities related to water supply and storage. The purpose of their statistics sets are to inform the general public about precipitation, river capacity and other types of hydrological data. The information appears to be timely and accurate, with current reservoir water levels reported on the home page. Finally, the source is appropriate for this project. It will provide background information about different reservoirs in Taiwan, their capacities and other relevant data for the project.

In a second example, the website of the company Tank Connection could be useful for the project. The site contains detailed information about the various tanks and systems they sell, including specifications, calculator charts and other product details. Again, the “About” page can be useful for learning about the company and their authority in the industry. The purpose of their specifications is to provide valuable data to current and prospective customers. It is important to remember the commercial purpose of the site and factor that into the evaluation. The information appears to be up-to-date and reflects current designs and products available through the company. Company websites may not be suitable to include in academic research depending on the project or discipline. In the case of our water storage project, the specifications can be particularly useful for modeling water storage options.

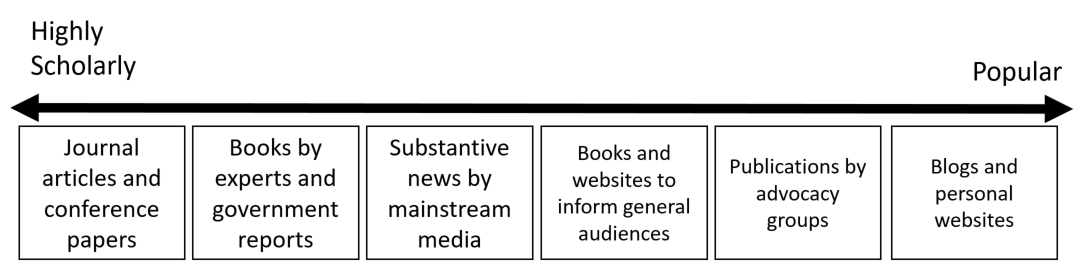

Sources exist along a spectrum and their suitability will change depending on the nature of the project. Most print sources will fall along the scholarly spectrum ranging from scholarly, peer reviewed journal articles to blogs and social media posts. The more scholarly end of the spectrum will form the basis for most academic research. The spectrum below depicts where print sources typically fall along the scholarly spectrum. Note, this is a typical scenario, blogs, websites or news maintained by government agencies or professional associations may be more scholarly depending on the topic and contents.

Sources will also exist along an authority spectrum unique to the specific project. The role of authority and the use of sources beyond scholarly articles are discussed more in Chapter 3. Essentially, you need to ask yourself two questions: 1) What type of sources will I need for this project and 2) Who (individuals and entities) are considered experts on my topic? The experts identified in question two will form the more authoritative end of your spectrum.

Tips for Effective Searching and Evaluation

To be an effective searcher, remember:

- Planning is key! You need to know what types of sources and information you are looking for. In addition to brainstorming keywords, do broad basic research if needed to gain a better understanding of the topic.

- Make time for reflection throughout the process. Periodically evaluating how your research is going will help you to make necessary adjustments.

- Match the type of information and search platform to your specific need. Just as flower markets don’t sell shoes, some databases and platforms specialize in certain kinds of information.

- Don’t be afraid to ask for help. Librarians can help you match your need to the right database or platform. They can also help brainstorm keywords and evaluate sources.

Questions to ask yourself when evaluating sources:

- Who published the source and what is their authority on the topic?

- What is the purpose of the source?

- Is it accurate and timely?

- How relevant is it for this specific project?

Reflection

Now that you have a more in depth understanding of finding and evaluating sources, consider the following in relation to a project or topic of your choosing:

- Put your search strategies into practice using a library website, Google Scholar, a disciplinary database or another collection. Consider:

- Are these terms and strategies returning the types of information I need?

- If not, how can I revise my search to get closer to what I need?

- Make an initial list of types of sources and entities that will be suitable for your project, consider how authoritative these sources are and what makes them suitable for the project.

- Take at least one of the items that you have found and practice evaluating. Consider how scholarly and/or authoritative it is, how reliable the information is, and most importantly, how it fits into your research.

- Sandra P. Thomas (Editor) (2018) Current Controversies Regarding Peer Review in Scholarly Journals, Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39:2, 99-101, DOI: 10.1080/01612840.2018.1431443. ↵

- Smith, R. (2006). Peer review: A flawed process at the heart of science and journals. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 99(4), 178–182. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.99.4.178. ↵

- Tennant, J.P., Ross-Hellauer, T. The limitations to our understanding of peer review. Res Integr Peer Rev 5, 6 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-020-00092-1. ↵