Introduction

The inhabitants of Europe did not identify themselves as Europeans on a wide scale before the Middle Ages. In all likelihood, prior to the modern period, most Europeans identified with their local community and kinship groups much more than they did with Europe. Certainly, ancient Greeks noted a cultural difference between themselves and their rivals, the Persians. Alexander the Great purposefully sought to deemphasize these cultural distinctions between Europeans and Asians; he encouraged his soldiers to intermarry with the local inhabitants of what had once been the Perisan Empire. Later, the pan-Mediterranean culture of the Roman Empire at least tempered this distinction between Europeans, Asians, and Africans. St. Augustine of Hippo, writing from North Africa in the 400s, would likely have found it laughable that he did not belong to the same culture as the bishop of Rome.

The crusades raised Latin Christians’ awareness of their collective identity. As the crusaders fought and traded with Greek Orthodox Christians and Muslims, the Latin Christians gradually viewed themselves as belonging to a culture that differed substantially from their rivals to the east and south. From the perspective of the Byzantines and the Muslims at the time of the First Crusade, the Latin Christians appeared to be rude, uncultured, and illiterate barbarians. While the tensions between the Latin Christians on one hand and the Greek Orthodox Christians and Muslims on the other persisted, the relationship between these groups changed as the western Europeans strengthened their collective identity and developed the rudiments of civilization during the High Middle Ages.

The Character of Civilization

Historically, civilizations began with the advent of cities in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus River Valley, the Yellow River Valley, and in Mesoamerica between 3500 and 1000 BCE. Because these civilizations featured permanent settlements, patriarchy, socioeconomic strata, and the ability to produce agricultural surpluses, they resembled the earlier Neolithic settlements that began in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere and spread northward and southward, sometime after the end of the last Ice Age, around 12,000 BCE. However, the culture of civilizations differed from the Neolithic predecessors in the size and the complexity of the settlements. In addition, the patriarchal and socioeconomic differentiation that developed in the Neolithic period became more pronounced in ancient city-states and empires.

As they first emerged around 3,500 BCE, cities often had upwards of 10,000 people and featured walls, monumental architecture, such as temples and funerary structures, and a bureaucratic elite who commanded the specialized knowledge of reading and writing. These cities also ruled over neighboring lands. No city was self-sufficient. The compact urban space with a dense population required external resources and agricultural labor to sustain the population. The rulers of these river-valley city-states typically resorted to exploitation and tried to justify their domination of rural workers by elevating themselves into gods or demigods and by convincing their subjects and later citizens that the administrators and their warriors deserved elevated status, rights, and material wealth. Therefore, the rulers often emphasized the distinction between these elites in the civilization on one hand and the slaves, immigrants, and foreigners on the other.

The term “civilization” often implies a qualitative advancement over other peoples, sometimes referred to as “barbarians.” The Greeks referred to the Persians this way even though the Persians had a very sophisticated civilization. The Romans wrote similarly about the Germans, whom they feared and employed as soldiers. Consequently, the term “civilization” may be offensive to some because of this bigoted differentiation, which implies the presence of the non-civilized. However, we decided to maintain the term in the title of this work because it reflects the persistent quest by the leaders of complex societies to dominate and conquer other people whom they deemed inferior. Conquest was often integral to civilizations because rulers raised their prestige and rewarded their elite followers by gaining control of more territory.

This propensity for the domination of resources through conquest encouraged leaders of civilizations to undertake two enduring policies. First, they tended to exploit both resources and people in order to control more of both. And second, civilizations provided luxuries that seduced their inhabitants so that they ignored or overlooked the exploitations that often damaged the environment and caused immense human and animal suffering throughout time. Reliable sources of cheap food, clothing, and entertainment have placated subject populations for millennia.

Although the phrase, “bread and circuses” is well known to those familiar with the Roman example, the poet of the Epic of Gilgamesh observed this tendency in Sumeria around 2,000 BCE. Writing about the Sumerian city-state of Uruk, the anonymous poet expressed admiration for the walls that offered inhabitants protection. Uruk also offered musical entertainment, street fairs, and resplendent clothing. However, these luxuries came at a price. The ruler, Gilgamesh, was a tyrant who slept with brides-to-be and impressed young men into his army. The people prayed to the gods for a remedy, which came in the form of an uncivilized being, Enkidu, who was seduced by the courtesan, Shamhat. In this very early piece of literature, Shamhat embodied the twin features of exploitation and seduction. Herself a victim of exploitation, she seduced Enkidu into joining civilization. Gilgamesh, the leader of the city who strutted like a bull in public and called on his mother for advice in private, understood how he could conquer his adversary, Enkidu, by recruiting Shamhat to seduce the barbarian.

The prescience of this early poet was not unique in the ancient world. Writing almost 2,000 years later, the Roman senator and historian, Tacitus, reflected on the expansion of the Roman Empire into northern Britain in Agricola. He dedicated the work to his father-in-law, Agricola, a celebrated military commander who led the Roman troops to victories. Agricola also understood the power of seduction to win peace. Tacitus described how the conquerors built temples, schools, and Roman baths in order to win over the subjugated Britons. He noted wryly that the Britons “called it ‘civilization,’ although it was part of their enslavement” (Agricola, 21). The seductive provision of amenities was a strategy used by the elite to gain the cooperation of subject populations.

Another strategy employed by the leaders of civilizations to expand their dominions involved the refinement of storytelling into myths that strengthened the collective identity and encouraged conquest. Students of American history will likely recall “Manifest Destiny” in our own country’s history to justify the conquest of the Western U.S. The Romans also developed their own conquest ideology, the Pax Romana, which emphasized that the Romans brought peace, law, and order to their subject peoples. Similarly, the Muslim Caliphate’s distinction between the abode of war and barbarism (Dar al-Harb) and the abode of peace (Dar al-Islam), emphasized the divinely-appointed mission of the civilized to conquer. These myths and many others shaped identities and inspired collective action.

In order to preserve and refine such narratives, rulers looked to the literate elites of their societies. Before the introduction of the phonetic alphabet, the skills of reading and writing were confined to the well heeled in ancient societies because literacy and writing were even more time consuming to master than they are today. Originally writing was the very specialized craft that took years to master because of the large number of symbols involved in pictographic communication. By contrast, reading was more accessible, but it required enough prosperity to expend time on studies. Learning to read and to write were luxuries beyond the reach of most of society, but they provided rulers and the wealthy with solutions to problems related to commerce, taxation, propaganda, and record keeping. Therefore, the rulers of civilizations nurtured not only poets and storytellers, but also bureaucrats, who helped to organize armies, to build temples to deities, and to regulate society. The obstacles in learning to read and write were typically not an accident. Priests and scholars operated at the heart of bureaucratic institutions that organized civilizations, and rulers and their advisors regulated access to these positions of power.

As literacy advanced in civilizations, the oral traditions of a preliterate age developed into more refined and complex mythologies that educated, re-educated, and entertained readers and listeners alike. The wealthy and powerful became patrons of poets who crafted familiar stories into revered myths that facilitated the growth of more uniform collective identities. Most of these narratives had kernels of truth to them, but the poets and scribes revised the stories to render them memorable, instructive, and appealing. The Hebrew Bible and Vergil’s Aeneid strengthened collective identities, as did Homer’s Iliad and Muhammed’s suras, the essence of the Qu’ran. Rulers sought to nurture such identities to grow their civilizations and to mollify diverse populations.

A uniform collective identity held the promise of widespread obedience and acceptance of social inequalities. Often religions promoted the existing social order and thereby promoted obedience; early Christianity as it emerged in the first and second centuries CE with its emphasis on the divinely favored poor was a notable exception. It was initially somewhat contemptuous of traditional authorities. Christians refused to recognize the divinity of the emperor. They rejected the materialism that was intrinsically attached to so many civilizations’ glorification of seductive comforts. When it became the religion of the emperors and later kings, Christianity’s emphasis on the divine favor cast upon the poor receded into the background. It became like other myths that glorified the rulers and their warriors. It gradually conformed to the patterns of myths that strengthened loyalties, encouraged obedience, forged collective identities that resembled an early form of patriotism.

The Concept Of Europe

Europe is the westernmost part of the Eurasian landmass, the largest continent on planet Earth. Although many people refer to Europe as a continent, it is sort of like India, an appendage to the largest continent. Sometimes those who refer to Europe as a continent cite the Ural mountains in western Russia as the boundary between Europe and Asia. Although the Urals extend for quite a distance and are rich in mineral deposits, their maximum elevation is unremarkable, and there is little justification for viewing them as a physical boundary separating two continents. No other mountain range divides two continents; bodies of water typically fulfill that function.

The willingness to assign continental status to Europe underscores Europeans’ tendency to view themselves as distinct from Asians, and perhaps vice-versa. Europeans have expressed their differences from Asians in racial terms even though the genetic composition of all humans on the planet is virtually identical. In short, Europeans have developed a strong tradition of viewing themselves as distinct from Asians and have gone so far as to claim that they inhabit a different continent and belong to a separate race. Both assertions are debatable or even false.

Similar to the ancient Greeks, Europeans have established a collective identity without forming a unified political state. The formation of the EU is an attempt to transform that collective identity into a political and economic system. Viewed from the longer term historical perspective, this push toward the EU is part of a broader attempt by humanity to expand the scope of political organizations from kinship groups and clans to nation-states, federations, alliances, and empires. Still, the definition of what constitutes as “Europe” remains somewhat ambiguous and EU membership problematic. Turkey, for instance, has sought admission, while Britain and other states have vacillated, despite the widespread recognition that Britain is part of what we traditionally refer to as “Europe.”

The evolution of Europeans’ tendency to view themselves with a separate collective identity has a long past that traces back at least to the ancient Greeks. They had their own language, shared stories or myths, and maintained many common customs and beliefs. Their willingness to lay aside their arms and engage in the Olympics exemplified their desire to nurture a collective identity that was in frequent tension with their loyalty to their city-states. However, the political unification of the Greeks only happened after conquest from the Macedonians in the fourth century BCE and again much later in the wake of the nineteenth-century nation-state movement when their perceived need to unite strengthened. Similarly, despite the European propensity to develop a collective identity, Europe’s transition from a conglomeration of nation-states to a federal Europe has faced many obstacles, such as strong attachments to a rich diversity of customs and traditions.

Another such obstacle is the lack of coherence about the essence of Europe. In other words, what is at the heart of European cultural identity? Since the 1700s when aspirations for democratic and representative governments gained many vocal supporters, such as Jacques Louis David, the histories of radical democracy in ancient Greece and especially the stability of government in the early Roman republic contributed to Europeans’ pride in their path-breaking efforts toward more representative governance. In other words, Europeans recognize a common past that emphasizes the struggle toward representative governance.

Similar to Rome between 500 and 100 BCE, Iceland between 950 and 1250 CE was a republic; Italian city-states featured republics in the centuries leading up to the Renaissance. However, representative governments were the exception rather than the rule in Europe’s more distant past, and even when they arose, they initially limited political rights to white, male property holders. Monarchies, constrained by powerful elites, have dominated European societies for most of the past 3000 years. To find the origins of European culture and the roots of its collective identity, one must look beyond the modern propensity toward representative and democratic governance.

The formative period for European civilization occurred between 1000 and 1300 CE, the High Middle Ages, when Europeans built cities, constructed monumental architecture, and organized universities that expanded literacy. During this period the population and wealth of Europe increased significantly, and political structures became more bureaucratic. Wars became more organized, and the ideology of conquest became more compelling with the crusades, which increased western European Christians’ awareness of their differences with Byzantines, with Muslims, and even with the Jews who often lived in Europe.

Although some conservative scholars have identified Christianity as the essential element of the European or “Western” collective identity, to do so would be overly simplistic. Certainly, since the Middle Ages, Christianity has provided Europeans with a common cultural framework, including values, beliefs, institutions, rituals, myths, and historical paradigms. Building upon the power of the Hebrew Bible to forge a strong collective identity, the Christian parables, along with stories of saints, heretics, and warriors, reinforced these values and beliefs. Prior to the advent of secular nation-states in the nineteenth century, Europe’s most influential leaders typically recognized Christianity as the state religion. However, Christianity fails to account for influential elements of European culture as it emerged as a civilization during the High Middle Ages, 1000-1300 CE.

During this period Europe’s warrior aristocracy embraced chivalry, often at odds with Christianity in its celebration of sexual intimacy and in its exploration of gender relations. Unlike the warriors of an earlier age, such as Beowulf or Byrhtnoth, these knights sought the love of a lady, read books, and practiced mercy. The romances of Marie de France and Chrétien de Troyes in the 1170s and 1180s stand in stark contrast to the attempt by St. Bernard to celebrate the celibate Templar as the ultimate form of knighthood in the first half of the 1100s. After the crusades brought Europeans into close contact with the more sophisticated civilization of the Islamic caliphate in the southern Mediterranean, European authors increasingly recognized the importance of a broader spectrum of emotions and more complex gender relations in their accounts of the human experience. Although the direct influence of Arabic literature, such as One Thousand and One Nights, on chivalry may be somewhat debatable, other Arabic and Muslim influences had clearer lines of influence in the High (1000-1300 CE) and in the Late Middle Ages (1300-1500 CE).

The crusader states and the Muslim scholars of the Iberian peninsula became vectors for the transmission of Arabic and Muslim ideas to Europe. Knowledge of algebra, the pointed-fifth arches, the three-field system, double-entry bookkeeping, and even the ancient Greek literature seeped into Western Europe from these Muslim vectors between 1100 and 1400. In other words, medieval Europeans often learned math, engineering, agricultural techniques, accounting, and Aristotle’s logic from their Muslim neighbors. Europe’s debt to Islamic civilization was substantial. But these two religions did not fully shape the essential elements of Europe’s civilization during the High Middle Ages. For more primordial and intrinsic features of Europe’s civilization, one must look to the pre-civilized cultures of Europeans during the Early Middle Ages (500-1000 CE).

During this period the Slavic, Germanic, and Celtic cultures that had existed in Europe north of the Alps for centuries increasingly came into contact with the Judaeo-Christian and Greco-Roman influences of the Mediterranean basin. The result produced a fascinating fusion. Christian scribes wrote stories of saintly heroes and warrior priests oftentimes in Latin but sometimes in the vernacular. Leaders of the Church officiated over rituals which had distinctly pagan origins, such as the ordeal. In Germanic Europe, Christian holidays assimilated pagan names, such as Easter, and activities, such as looking for eggs, a symbol of fertility. And in both Celtic and Germanic parts of Europe, the love of storytelling, ancestors, and heroic deeds received a preservative: the Judaeo-Christian attachment to writing.

In the early phases of this process of fusion, much of the pagan Greco-Roman tradition remained relatively unknown, partly because the Church exercised enormous control over the preservation of manuscripts and access to ancient knowledge. The writings of Greco-Roman playwrights, philosophers, and other scholars would have to wait until humanists uncovered manuscripts during the Renaissance before many of these Greco-Roman masterpieces became part of the intellectual canon of European civilization. Between 500 and 1000 CE the cultures north of the Alps remained fairly provincial and mostly illiterate. However, those cultures provided some of the seeds of the civilization that blossomed after 1000 CE.

By the High Middle Ages (1000-1300 CE) commercial activity increased significantly, and consequently, so did literacy. Commerce had fostered literacy since the development of cuneiform in ancient Sumeria in the fourth millennium BCE. As Europeans traveled both for warfare during the crusades and for commerce across the Mediterranean Sea, they increasingly absorbed features of the Greco-Roman civilizations of the past and the Muslim civilization of their present. The Muslims also acted as intermediaries for the transmission of ancient Chinese discoveries including paper making, gunpowder production, and possibly moveable type. By the 1300s, Europe had all the makings of a complex and sophisticated civilization.

The demographic collapse during the 1300s, mostly caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, altered the fundamental structure of European society when the relative size of Europe’s middle class expanded. The plague also undermined respect for the hierarchy and customs that had evolved during the High Middle Ages. This contempt for Church officials, oligarchs, and even patriarchs became more vocal right around the time that Giovanni Boccaccio wrote a somewhat fictionalized account of the Black Death in Florence in his Decameron (c. 1350 CE). The growth of the middle class and the rising willingness to challenge obedience to corrupt authorities persisted. By the modern period, Europeans had developed a cultural propensity for challenging monarchs, popes, and other tyrants. This trend eventually inspired not only calls for republican governments, but also the Jacques Louis David painting above. Completed in the months leading up to the French Revolution (1789 CE), it emphasized the importance of loyalty to a republic; the common good, the res publica, trumped loyalty even to family.

David himself was the beneficiary of another big trend of the Late Middle Ages (1300-1500 CE): increased innovation. For centuries Europeans had been so attached to traditions that, compared to the Chinese and the Muslims, they were very slow to adopt innovations, often thought to be the work of the Devil. In the 1300s most elites still eschewed both paper for documents and Arabic numerals for math even though they had known about these innovations for centuries. Although the first official indices of prohibited books did not appear until the 1500s, the Church had tacitly and covertly suppressed pagan Greek and Roman authors for centuries. One of the first steps of this increased tendency toward innovation involved the recovery of lost ancient knowledge. Often inspired by the belief that knowledge was in decline, humanist scholars first in Italy in the 1300s and then later across much of Europe undertook the recovery of that knowledge by foraging in monastic archives and by journeying to the more cosmopolitan milieu of Islamic scholarship.

This quest for wisdom coincided with the growth of the middle class and the contempt for authority in the wake of the plague. Transformative, technical innovations coincided with literary and artistic achievements, sometimes referred to as “a renaissance,” a rebirth of knowledge that harkened back to the great achievements of the Greeks and Romans. The printing press, the adaptations to gunpowder, and the proliferation of navigation technology, including maps, ship design, and compasses, transformed Europe’s relationship to the rest of the world. No longer a cultural backwater, Europe became the cradle of great art, literature, architecture, and many other accoutrements of a sophisticated civilization. That is where this volume ends.

Abandoning “Western Civilization”

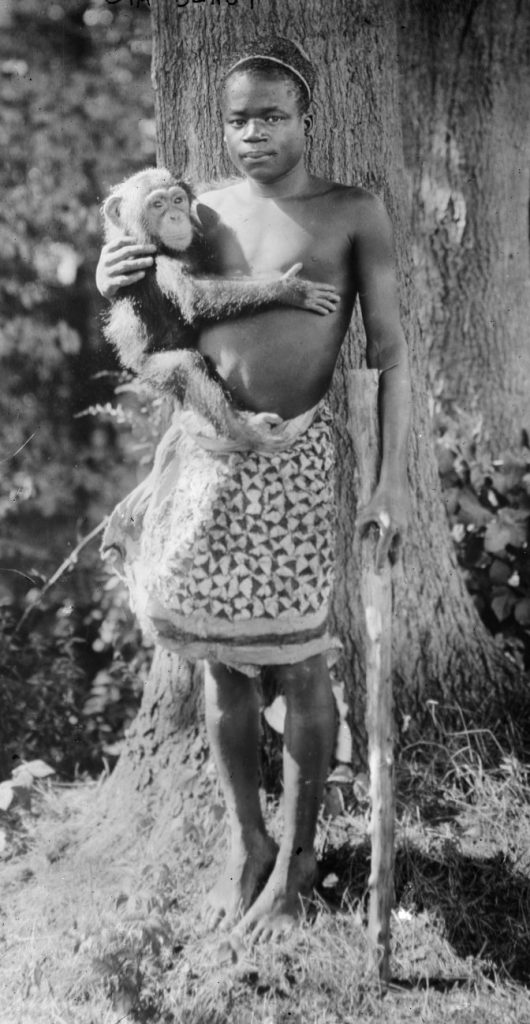

For over a century, historians have often addressed the history of Europe under the heading of “Western Civilization,” which also included the history of the Americas, especially North America. However, the concept of “Western Civilization” is problematic for a number of reasons. Europeans had employed it with the hope of drawing Americans into conflicts that European imperialism had created. In addition, the concept of “Western Civilization” was racially charged. It implied an advanced civilization, which then justified exploitation, conquest, and conversion. By the late 1800s Europeans had conquered and colonized most of the world as they spread their religions. Perhaps no event captures European civilization’s hegemony and the accompanying tendency to exploit people and resources than did the 1884-1885 Berlin Conference, where Europeans partitioned Africa into colonies. And perhaps no photo reflects this sense of racial superiority more than the picture of Ota Benga (left), a 23-year-old Congolese man, whom Americans placed in the Bronx Zoo in the early 1900s.

Following the lack of U.S. popular interest in engaging in World War I, Europeans, and the British in particular, increasingly developed curricula in European history courses that tied U.S. and especially western European histories together under the rubric of “Western Civilization.” Since that time, the term has increasingly become polarizing, used both by Osama bin Laden and by white nationalists in the U.S. and elsewhere. Defenders and critics of this concept often point to some combination of Christianity, democracy, capitalism as defining characteristics of civilizations that emerged in the west, much as we have done with the origins of European civilization; however, they often skip over the cultural debt that Europeans incurred as they imported knowledge and technology from Middle Eastern and Islamic civilizations. They also minimize the exploitation that happened in the name of Western religions. These oversights tend to aggravate the racist and imperialist implications of “Western Civilization” as a lens for understanding the past.

The defenders of this terminology often emphasize the seductive elements of civilization: freedom, material possessions, cultural achievements, claims to moral superiority, and so on. The critics of “Western Civilization” point to its exploitative elements: environmental destruction, shallow materialism, and human exploitation, including racism, classism,and patriarchy. Although many who continue to employ the terminology of “Western Civilization” are not racist, imperialist, or sexist, we find that the term unnecessarily clouds our understanding of Europe’s past and have chosen to jettison it.

The authors of this edition commend the prospect of removing borders between humans so that we can start to think more about the problems facing all of humanity and less about the problems faced by a particular nation or people. We also sense that framing our understanding of the past in terms of “Western Civilization” is actually counterproductive to solving the global problems that have become more pronounced in the twenty-first century: pandemics, extreme wealth disparities, authoritarianism, mass extinction, and human suffering. To perpetuate the history of a “Western Civilization” only exacerbates these problems. Meanwhile, an evaluation of the defining features of European civilization as they developed over several centuries has more potential to promote the unified and cooperative initiatives that are likely to help humanity address the crises of the twenty-first century. Consequently, this volume focuses on the origins of European civilization and encourages Europeans and others to recognize that Europe’s meteoric success in the modern period owed a great debt to its Asian and African neighbors in the pre-modern and modern periods.