14

Introduction

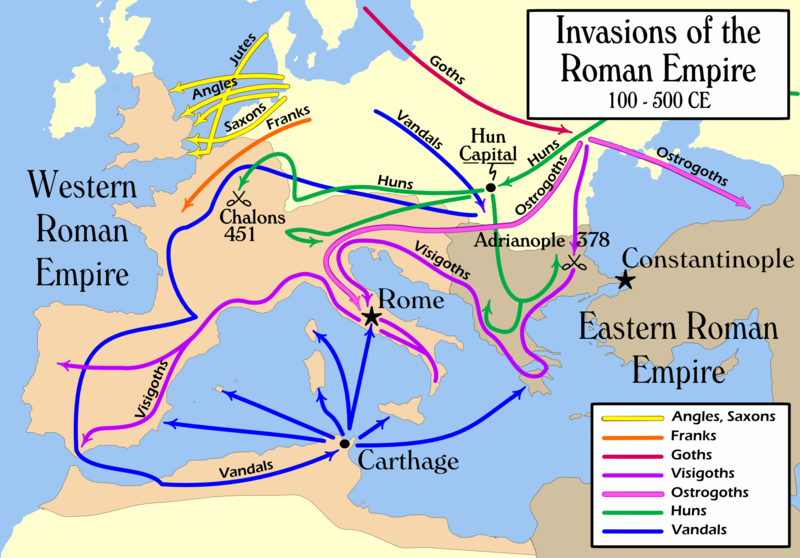

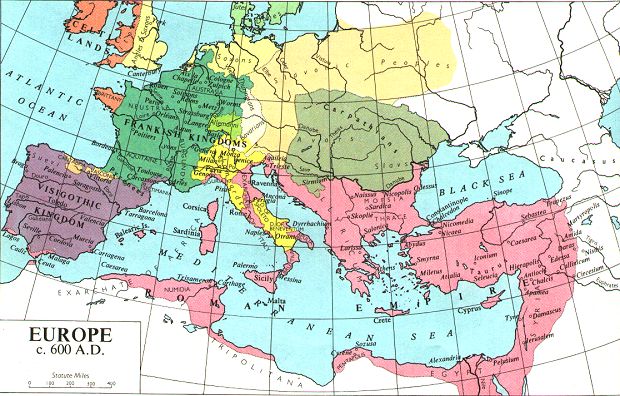

As the centralized imperial authority in the Western Empire gradually deteriorated during the fifth century CE, the previously stable boundaries between the Romans and the Germanic tribes, who had mostly remained north of the Danube and east of the Rhine rivers, became increasingly porous. This instability along the western frontiers contrasted with the Eastern Empire, which had maintained fairly stable borders until the early seventh century and could draw tax revenues from a larger number of cities to maintain the central imperial administration. The Western half of the Empire had always fewer and smaller cities than the Eastern portion, and this structural difference weakened the Western Emperors’ ability to fend off mounting pressures from invaders.

Following the catastrophic loss to the Vandals in the naval battle of Cape Bon off the coast of North Africa in 469, the Eastern emperors realized that they could no longer afford to subsidize the military operations necessary to maintain political stability in the Western Empire. Germanic chieftains had already carved out areas of control in parts of modern-day Italy, Germany, France, England, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Meanwhile, different groups of Celts also took advantage of western imperial weakness. They revolted in Brittany against Roman rule while Celtic Britons failed to protect previously Roman dominions south of Hadrian’s Wall from a variety of invaders. Suffering from incursions of Pictish and Irish raiders, southern Britain succumbed to Germanic invasions during the mid-400s. Centralized imperial authority in Western Europe gradually diminished during the fifth century.

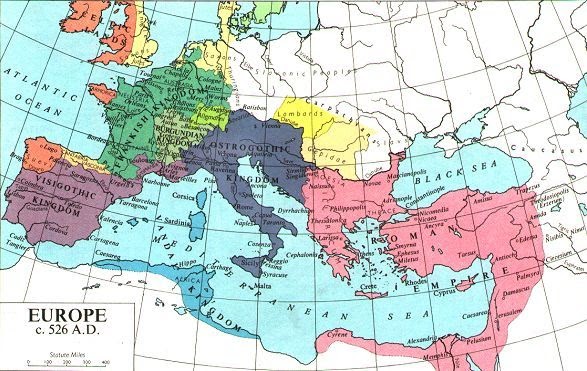

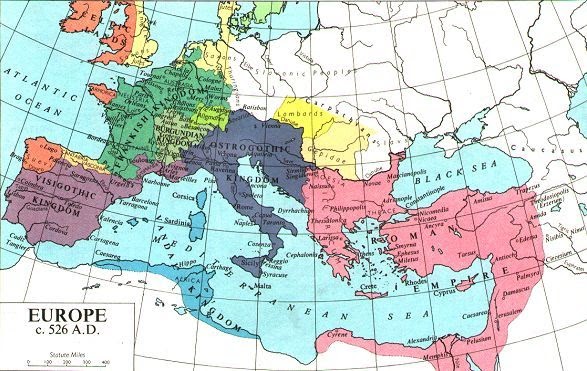

Invasions spread across Gaul and Britannia. Vandals, Goths, Burgundians, Saxons, Angles, and Franks migrated over the traditional borders of the empire and fundamentally altered the language, customs, and social organization that had characterized these northern provinces. This transformation of western imperial lands was often violent and disruptive. The invaders seized land, enslaved people, and weakened the infrastructure of the civilization that the Romans and their subjects had developed. The populations of cities shrank, commerce dwindled, and intellectual activity became more parochial, less cosmopolitan. Gradually in most cases, more quickly in others, the so-called “barbarian kingdoms” formed. These new political entities established a framework for the medieval fusion between Germanic and Celtic cultures on one hand and the Greco-Roman and Judaeo-Christian influences on the other.

This fusion laid a foundation for the Western European Germanic and Celtic cultures that have endured for centuries. A similar process happened in the Eastern Empire between the sixth and eighth centuries when Slavic groups wrested control of the Balkans from the Eastern emperors. However, the formation of barbarian kingdoms that featured written laws, royal decrees, and bureaucratic administrators manifested later in areas that had not previously been part of the empire. Germanic tribes, such as the Franks, Burgundians, and Goths adopted some Roman administrative practices, often through the agency of Church leaders who had remained in place during the invasions.

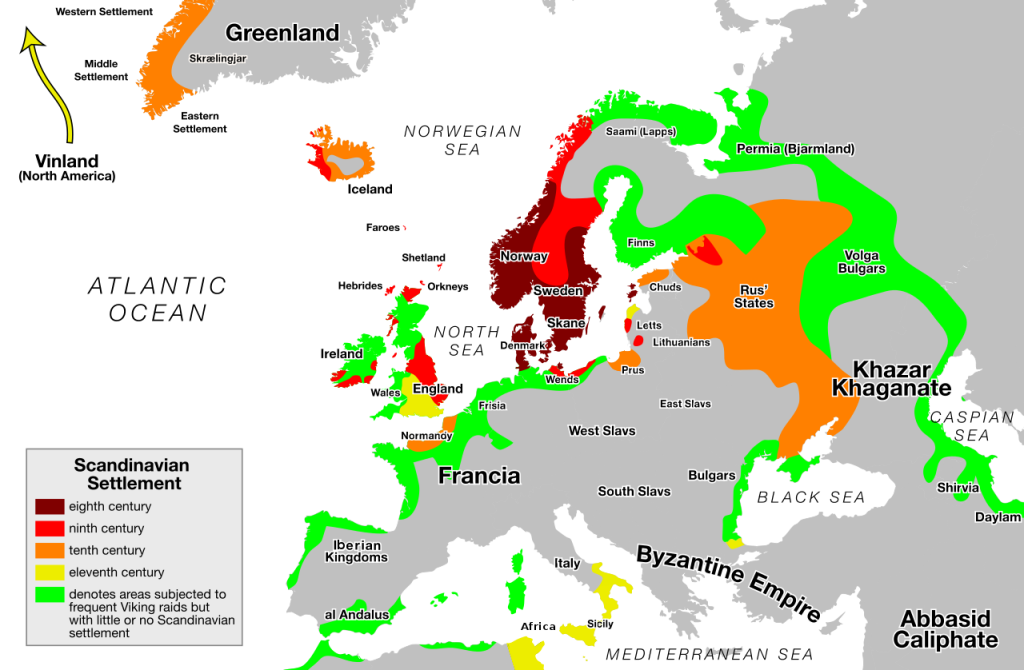

As missionaries from Rome and Constantinople proselytized north of the Pyrenees, Alps, and Balkans, the so-called “barbarian” cultures of Celts, Germans, and Slavs very gradually fused with Christian customs and traditions to produce disparate variations of Christianity. These localized adaptations of the faith slowly shaped collective identities throughout Europe. Further north, in Scandinavia, the process came much later, near the end of the early medieval period and even into the High Middle Ages (1000-1300). Although some Scandinavian kings, such as Harold Bluetooth and Olaf Tryggvason embraced the faith in the tenth century, their people only gradually understood and adopted the kings’ religion. People with less centralized authority, such as the Sami in Finland, converted much more slowly. They did not become Christian until the eighteenth century.

This process of fusion between barbarian and Christian customs and traditions also included Greco-Roman cultural influences, which were more pronounced south of the Alps. The Visigothic kings in modern-day Spain used Latin as the court language and were quite familiar with the laws and customs of the Romans. Further north, the Merovingian Franks wrote a Latin legal code and absorbed enough Roman influence to develop a Romance language, centered on Latin, instead of a Germanic language. The Church often provided the primary vehicle for the preservation of these Greco-Roman influences, but collective memories of the imperial achievements of the Romans also sparked the desire to preserve the Roman legacy. In response, Church leaders often sought to repress writings by pagan authors who expressed thoughts contrary to Church doctrines.

Although some historians have tended to view the Early Middle Ages as a “Dark Age,” the terminology is overly dramatic. Typically, a “dark age” occurs when contemporary written sources fail to illuminate the events of the period. And while many Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic leaders were pagan and illiterate around 500 CE, most rulers identified as Christian by 1000 CE. As they converted, they adopted the Christian practices of writing and record keeping. Some kings, such as the Frankish king, Clovis, and the Visigothic king, Alaric, were already Christian by 500, and they too produced written sources. Therefore, while the Early Middle Ages had many features of a dark age, including widespread violence, the decline of urban centers, and the dwindling of trade, the period also featured pockets of literacy. Monasteries, in particular, provided sanctuaries for monks to write explanations of the often violent and disruptive events that accompanied the transition away from centralized imperial authority toward more localized leadership.

At the beginning of this period the leaders of these Celtic, Germanic, and Slavic groups were primarily commanders of warbands. They were adept at raiding, plundering, and distributing spoils to loyal warriors. Their ability to rule civil society was limited. Instead, they left dispute settlement practices to families and kinship groups. Locally, minor chieftains formed marriage alliances, oversaw judicial practices such as the ordeal (described below), and brokered cessations of violence by offering compensation to injured parties in a dispute. Especially before the conversion to Christianity and often afterwards, these local leaders had no written laws, no trained jurists, and no cadre of bureaucrats to issue written commands or to account for taxation. Only gradually, spasmodically, and unevenly did more localized chieftains and kings nurture enough literate clerics to perform some of these functions. The sustenance of a central administrative government proved to be one of the enduring challenges of the Early Middle Ages, and many local rulers, such as warband leaders and later members of the warrior aristocracy, opposed the formation of a bureaucracy as an infringement on their autonomy.

The Celts

Long before the Germanic invaders occupied most of central and western Europe during the late 300s and especially during the 400s CE, Celtic peoples had fought against the Romans, both north and south of the Alps. The Celts in northern Italy, called “Gauls,” sacked Rome around 378 BCE, when Rome was still just a growing city-state in the central Italian peninsula. The Romans came to fear these Celts, who fought with notable bravery. Similar to the Germanic peoples, Celts were relatively slow to develop a strong collective identity that unified many different groups even though they spoke similar dialects of a common language, Gaelic. Consequently, with only localized political unity, they occupied various regions: Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Cornwall, Brittany, Gaul, and even as far east as Galatia, in Asia Minor (Anatolia). Just as there was no king who commanded control over all of Germania or Slavia, there was no single king of the Celts; instead, they organized themselves more locally with strong familial attachments.

Because the Celts in Gaul rarely acted in concert, Julius Caesar took advantage of their local rivalries and played one group of Celts against another as he conquered Gaul during the middle of the first century BCE. One hundred years later, the middle of the first century CE, the Celts in Gaul were so deeply entrenched in the Roman Empire that their leaders became members of the Roman Senate. Other Celts, such as the Britons, joined the empire after conquest from the Romans. Gradually, the Romans integrated many Celts into the imperial administration, much as they latter did with Germanic leaders. Although some Celts eventually considered themselves Romans or allies of the Romans, relations between many Celtic peoples and the Romans were often tense or even hostile. One notable example of this tension occurred in 60 CE when the Celtic queen, Boudicca, amassed an army and destroyed Roman outposts in southeastern Britain. This uprising against Roman rule happened about 15 years after the Romans had first extended their conquests over southern Britain during the mid 40s CE.

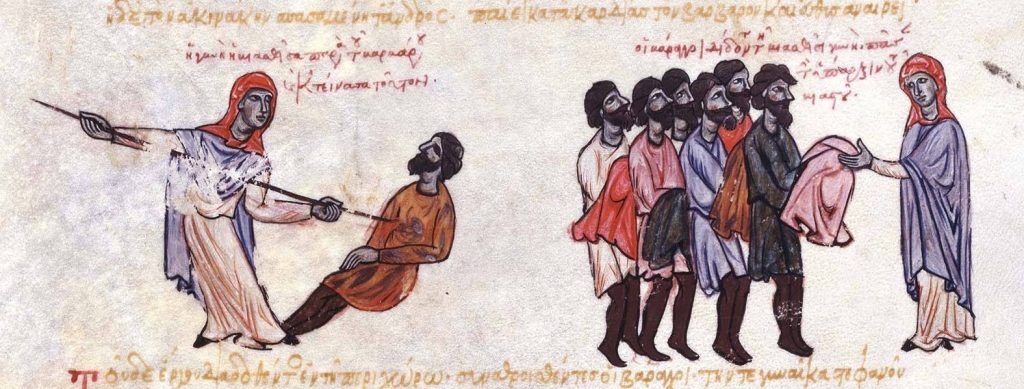

The Celts differed from the Germans in that they spoke different languages (variations of Gaelic), organized their social relations less patriarchally, practiced different customs, and produced distinctive artwork. While both cultures promoted warrior chieftains, the Celts apparently regarded women–and especially aristocratic women–with more respect than the Romans or the Germanic peoples. Boudicca’s uprising in 60 CE reinforced the image of a powerful female leader as portrayed in the Celtic epic, the Táin Bó Cúailnge. The story recounts the deeds of the warrior queen, Medb, who engaged in cattle raids against her local enemies. Later, when the Celts absorbed the teachings of Christian missionaries, they maintained this relative respect for women by recognizing female abbesses who ruled over both men and women in their monasteries. During the Early Middle Ages neither the Romans nor the Germans developed customs that recognized the abilities of women to rule a monastery or a kingdom.

Despite similarities among Celtic groups, they varied quite significantly from one place to another. Writing in the early eighth century, the monastic historian Bede noted that the Celts in Ireland differed from the Celts in western Britain (modern-day Wales). The Irish Celts embraced the Christian propensities for asceticism and especially evangelism more readily than their British Celtic brethren. This distinction is understandable. The British Celts in Wales had been victims of the Germanic invasions, and they were less inclined to save the souls of their tormentors: the Angles, Saxons, and other Germanic warriors. However, the differences between Celtic Christians reflected a predilection for more decentralized authority. Unlike the Latin Church, which established an organizational hierarchy, the Celtic Christian leaders allowed for more local autonomy and variation. Some Celts embraced the practices of the Roman Church by the early seventh century while others maintained regional practices until the eighth century, allowing abbots or abbesses to determine doctrinal practices rather than adhering to the dictates of a far-away bishop.

Because of their relative isolation from the Mediterranean basin, where Christianity first developed in an urban context, the Celts often adapted Christianity to reflect the more rural and tribal conditions of Celtic culture. This fusion of Celtic and Christian cultural practices assumed several forms. For example, with their relative respect for women, Celts established dual-gendered monasteries, notably absent in the Latin Church, and sometimes had female abbesses. The strong attachment to family that characterized Celtic culture inspired the practice of green martyrdom, a form of suffering that emphasized deprivation and hermitage, divorced from the attractions of being connected to family.

These green martyrs did not suffer the bloody torments of lions in the Colosseum, as previous generations of Roman martyrs had done, but they isolated themselves away from family in remote enclaves in order to focus on their piety and to endure prolonged suffering, as part of the Christian propensity to practice asceticism. Likely inspired by the life of St. Patrick, who converted the Irish in the first half of the 400s, Celtic missionaries undertook the Christian duty to evangelize with notable zeal. Their green martyrdom combined with their evangelical zeal to inspire Celts to establish monasteries across Western Europe in a path between the British Isles and Rome. In these monasteries, they preserved numerous Christian and Greco-Roman texts. Differentiating themselves from Roman or Benedictine monks, who were often less tolerant of pagan classics, the Celtic monks typically sported a different haircut, called a “tonsure,” that visibly identified them as Celtic instead of Roman or Latin Christians. Finally, because they tended to be less averse to preserving pagan classics, Celtic monks contributed significantly to the literary achievements of the Early Middle Ages, thereby contradicting the notion that Europe was undergoing a dark age.

Germanic Peoples

The success of the Germanic peoples in the domination of most of Europe between the time of Julius Caesar in the first century BCE and the sixth century CE is not well documented. Many of them were exceptional warriors, blessed with height and perhaps strength beyond the norms of Roman experience, and the Romans both feared and admired them. The Batavians, who lived near the mouth of the Rhine River on the North Sea, were so renowned for their martial skills and physical stature that the Roman emperors employed them as their personal retinue, the Praetorian Guard. Many other Germanic warriors served in the Roman legions, and they learned the logistical, technological, and organizational practices that made Rome’s legions so effective at war. Writing in the late first century CE, Tacitus felt compelled to catalogue the Germans’ cultural traits in Germania. Implicit in his work was an awareness of the Germans’ success in remaining free from Roman rule. Tacitus’ descriptions of the racial purity of Germanic tribes served as a misguided explanation for their martial success. This idealized view later inspired nineteenth and twentieth-century Aryan spin doctors, including the Nazis, to portray the Germans as an uncorrupted and, supposedly, biologically superior race. This myth is embedded in the terminology of “Western Civilization,” which often glorifies western cultures and peoples.

One explanation for the Germanic dominance of Europe focuses on the incredibly violent and martial nature of their culture. Of course, the Romans and the Greeks before them had celebrated warrior prowess, and all of these cultures awarded political rights to those who had demonstrated their military skills in service. However, violence was apparently deeply embedded in Germanic warrior culture. Well into the tenth and eleventh centuries, Scandinavians celebrated young men who went viking, a term that involved travel, conquest, trade, and plunder; this verb is the origin of the people known as Vikings, discussed below. The Germanic people often buried their warriors with their weapons and with their plunder, and their burial mounds sometimes featured not only trophies of war, but also the vehicles for conquest–ships filled with weapons– in addition to armor, coin collections, favored animals, and other prized belongings. In short, because pagan, Germanic peoples were illiterate, our understanding of this violent warrior culture relies quite a bit on outside observers, such as Tacitus, and on archaeological evidence, often found at grave sites.

Following the Germanic peoples’ conversions, missionaries and monks recorded enough elements of their culture in legal codes and in accounts of enduring customs, embedded in poetry, that historians now have a fairly solid understanding of the warrior culture that dominated Germanic societies. The conversion of these illiterate, materialistic, and violent people to a religion that emphasized a holy book, asceticism, and turning the other cheek underscored the pliability of the Christian religion. The process of conversion mostly occurred between the 300s to the 900s and, once converted, the inculcation of Christian beliefs and traditions often took centuries to complete. As a consequence of this protracted process, Germanic practices which predated the conversion, such as the ordeal and the distribution of plunder, survived into the High and even Late Middle Ages in some areas.

Despite their command over violent warriors, Germanic kings were relatively weak in terms of their influence on civil society. They were essentially warband leaders, who commanded cohorts that frequently participated in raids and warfare. Often aware of the legendary power of the Roman emperors, these kings sought to increase their authority, and many of them viewed the Church as an ally in elevating their prestige above rival chieftains. Although these kings gained much more control over legal actions and the regulation of society during the High and Late Middle Ages, during the Early Middle Ages weak kingship and strong kinship characterized early medieval Germanic societies. Patriarchal clan leaders adjudicated disputes and regulated social relationships. These chieftains tended to have more localized authority than the warband leaders, the kings. Very gradually, with the adoption of Christianity the power of the kings waxed and the chieftains ceded some control over civil society to the emerging dynasties of monarchs.

In the meantime, kings needed to placate the chieftains and other leaders of kinship groups. The power of kinship groups and communities of warriors was deeply rooted in rituals such as “the ordeal,” derived from the Germanic word “Urteil,” meaning judgement. In contrast to later judicial processes, run by legal experts who were educated and trained in the nuances of legal precedents and laws, the early medieval Germanic peoples maintained social practices to resolve disputes. Local patriarchs, chieftains, and priests endowed such social practices with an aura of formality and solemnity, but the consensus of free men (warriors) in attendance imparted a sense of acceptance by a community as to the judgement.

Although many variations developed, the ordeal had two principal forms. In the bilateral ordeal, a physical fight typically settled disputes. A warrior represented his clan or kinship group against another warrior to find at least a temporary resolution to a dispute. In the unilateral ordeal a challenge faced the accused. This challenge could involve fire, water, or especially after the conversion to Christianity, the swearing of an oath. If the accused was successfully acquitted in the face of one of these challenges according to the judgement of the community, then divine judgment was clear. Some of these rituals endured well beyond the conversion to Christianity. Trial by water was still practiced in England during the reign of Henry (1154-1189), and the Church allowed clergy to add an aura of legitimacy to such proceedings until the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215.

The ordeal was not the only method that early medieval Germanic society had to settle disputes. The ordeal tended to be for serious matters that could not be settled merely by compensating the victim or plaintiff in a dispute. Germanic kings and chieftains tended to prefer compensation to the bilateral ordeal as a method of settling disputes because it was less destructive for the group. Like the ordeal, this method was also very ancient. Prior to the use of precious metals, Germanic peoples used cattle as a medium of exchange to pay for their offenses. By the end of the first century at the latest, the Germanic peoples who lived closest to the Romans adopted gold and silver and even Roman coins. The groups in central and eastern Europe, especially those more removed from imperial borderlands, slowly adopted precious metals although barter remained common across much of Europe well into the Early Middle Ages. By the end of the sixth century, the kingdom of Kent in southeastern Britain produced the earliest written document in the English language, a legal code known as the Laws of Aethelberht of Kent, which outlined a variety of monetary compensations for various crime.

These laws reflected the violence that plagued early Germanic societies. Produced within only a few years of the king’s acceptance of Christianity, Aethelberht’s legal code consisted of dozens of compensations paid to plaintiffs for a variety of violent acts ranging from homicide to damage to a person’s fingernail; even a black eye could be grounds for compensation. The compensation would be in measures of silver, described as a shilling, which consisted of one twentieth of a pound or a little less than an ounce. Monetary payment for injuries might well have been an effective method for settling disputes, just as they are today when plaintiffs demand damages in lawsuits. At the very least these payments forestalled feuding, a form of self-help practiced by families and their allies across much of Europe throughout the early Middle Ages. Kings, such as Aethelberht, had an interest in limiting feuds among their warriors so that they could keep their warbands intact for attacking groups outside of their kingdoms. Despite the kings’ efforts to maintain social cohesion, infighting within kingdoms or warbands was one of the most persistent obstacles to the formation of civilization in Europe. And monetary compensation provided one of the easiest ways to avoid such infighting.

Even though none of Aethelberht’s warriors could read his legal code when missionaries first sounded out the Germanic language of the early English, the code constituted an attempt to elevate the prestige of the king, to increase his authority in matters of dispute settlement. Initially more of an ornament that a king could point to rather than a practical guide to running a legal system, these early folk laws reflected the quest by Germanic kings to establish their authority in civil society. Powerful warriors and chieftains, later called nobles, recognized the threat that such legal innovations presented to their localized authority and prestige. They often resisted the extension of royal power–and the writing and literacy that facilitated it– well into the High and Late Middle Ages. Consequently, the establishment of royal courts and jurisdictions proceeded very gradually over hundreds of years because the king’s right to settle disputes had not been a common practice.

In continental Europe, the Germanic legal codes often operated side-by-side with Roman law. The earliest of these codes, the Burgundian and Visigothic codes, included a number of Roman judicial principles and preceded the early English example by a century or more. The Romans had previously established their institutional and linguistic influences in these areas far more effectively than they had in northern Gaul, where the Salian Franks produced a legal code that more closely resembled the Laws of Aethelbert. In all of these continental codes, the Franks, Burgundians, and Visigoths employed the remnants of Roman imperial administration, mostly in the form of bishops, jurists, and counts. The Romans had a penchant for establishing an institutional hierarchy for governance, and this structure continued in areas such as Gaul and the Iberian peninsula, where Roman governance had been uninterrupted for centuries. Although the Romans had ruled southern Britain for 400 years, the Roman administration of law had ceased to function in Germanic Britain well before the mid fifth century, 150 years before the laws of Aethelberht.

In addition to reflecting the violent character of Germanic society, these legal codes also conveyed a fairly extreme form of male domination. The Franks only allowed inheritance through the male line, and the early English allowed men to purchase women. Although noblewomen had more legal rights than commoners, a Frankish noble who married her slave lost her property and became an outlaw, meaning she no longer had the king’s legal protection. Since law was a form of privilege in Germanic culture, noblewomen who produced male heirs typically had greater legal protection than unwed or childless women by virtue of their enhanced social status or standing. In Aethelberht’s code a woman could receive half her husband’s property if she bore a child before her husband died. The Franks had severe penalties, including death and outlawry, for rapists. Nevertheless, the Germanic legal codes only offered minor protections for noblewomen, who often appeared in the codes as dependents or property. In all likelihood, peasant women and men had few legal rights in these societies.

Early Germanic literature also reinforced the violent and patriarchal values evident in the laws. This literature did not appear in abundance until centuries after the conversion to Christianity. However, it often portrayed characters and events from an earlier era. For example, Beowulf was likely composed around 800, although its date of composition has remained the subject of intense scrutiny and debate. Despite this disagreement, it is fairly clear that an anonymous Christian scribe wrote the only existing manuscript of the poem around 1000. The language of the poem was clearly from a much earlier period, probably around 800. Perhaps it existed in a now lost manuscript or in an oral tradition before a scribe copied it down in the eleventh century. Regardless, the poem described the exploits of a legendary warrior who lived during the sixth century. It alluded to feuding and the ordeal. It celebrated martial prowess and gave scant attention to women. Beowulf, the titular pagan warrior in the poem, never married or produced an heir. He was apparently too preoccupied with attaining glory by winning battles. This epic viewed the pagan, Germanic hero from centuries past through the lens of a Christian scribe to a Christian, English and Anglo-Danish audience, apparently with the dual purpose of portraying the limits of pagan wisdom and virtue and of strengthening the faith of its intended Christian audience. To understand this point further, we must turn to the defining features of early Christianity as it arose in the Latin Church.

The Latin Church

After the fall of the western Roman empire, the Church provided some continuity with the Roman imperial administration and gradually fostered a sense of a collective European identity, which in itself constituted a unifying force among the ethnically diverse population of Germanic and Celtic peoples who inhabited western Europe. It actively extinguished the so-called “pagan” religions, despite the political fragmentation left in the wake of the fall of Rome. By the time of the First Crusade at the end of the eleventh century, if not before, most European leaders west of the Balkans understood that they were members of the Latin Church governed by a hierarchy of prelates with the bishop of Rome as its leader. For the sake of clarity, this chapter will use the term “Latin” instead of “Catholic” to describe the western Church based in Rome during this period, because both the western Latin Church in Rome and the eastern Orthodox Church in Constantinople claimed to be “catholic,” which means “universal” when in lower case. In addition, the practices of the Latin Church differed substantially from the Roman Catholic Church after the Council of Trent redefined features of the faith during the mid-1500s.

The Latin Church preserved at least some of the legacy of ancient Rome. Archbishops, bishops, and priests served as administrators in every Christian monarchy in Europe throughout the Middle Ages. Some administrators functioned as treasurers and judges, and others were diplomats, educators and propagandists. While these clerics preserved knowledge of Roman laws and maintained the type of literate bureaucracy that had accompanied civilizations since Sumerian origins, they also actively suppressed certain Greco-Roman texts deemed incompatible with Christian beliefs. For example, Aristotle had claimed that the sun revolved around the earth, a concept that the Christian Bible reinforced, mostly in the Old Testament; Latin Christian monks preserved some of his works and discarded others. By contrast, Aristarchus of Samos viewed the sun as the center of the universe, a view incompatible with the centrality of humanity perpetuated in Latin Christian thinking. His works were virtually unknown in early medieval Europe.

Despite this selectivity, the Church preserved fundamental elements of the intellectual traditions of the Roman Empire even in the wake of Celtic, Germanic, and Slavic invasions. Although Latin faded away as a spoken language, all but vanishing by around the eighth century even in Italy, the Bible and written communication between educated elites were in Latin. By 700 Latin had transformed from the common language of the Roman Empire to the written language of the educated elites all across Europe. Some members of the clergy could not only write but speak in Latin. They corresponded in Latin with other members of the European clergy via letters and sermons. This communication was unlikely to occur in the vernacular because local languages varied so drastically.

By contrast, some members of the Church were exceptionally persuasive in the vernacular. Christian missionaries converted kings and chieftains who had no knowledge of Latin. Although pagan armies sometimes defeated Christian opponents, from the Germanic invaders who had dismantled the western empire to the Slavic peoples who fought the Byzantines, many kings gradually recognized the allure of the religion of the Romans. Conversion often took place both because of the astonishing perseverance of missionaries and because of the desire of non-Christians to improve political relationships with Christians. Nevertheless, forced conversions occurred, most notably in the case of Saint Olaf Tryggvason, who allegedly forced a snake down the throat of a reluctant convert. Whether through heartfelt conversion or force, most Europeans were either Latin or Orthodox Christians by the First Crusade (1096-1099).

The Bishop of Rome

Between the 300s and the 600s the Latin Church gradually coalesced under the leadership of the Bishop of Rome, later known as il papa, the pope. As early as 325 the Bishop of Rome was the most senior of five patriarchs recognized by the Roman emperors. These patriarchs were the leaders of the Church who lived in Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria. Each patriarch had dozens of bishops under his authority. However, ultimate authority in the Church during this period rested mostly in Church councils, which were gatherings of all the bishops and patriarchs of the Church. These councils established religious doctrines called “orthodoxy,” which meant “straight thinking” in terms of beliefs and practices.

After the fall of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria to Islam during the 600s, the patriarchs of Constantinople and Rome exercised greater autonomy within their own dominions. By 700 Church councils became less frequent and less ecumenical, meaning that they became more compartmentalized into eastern and western sects, with the Patriarch of Rome ruling over Western or Latin Christendom and the Patriarch of Constantinople ruling over Eastern or Byzantine Christianity. Consequently, Latin and Byzantine religious beliefs and practices gradually diverged over a number of issues, culminating with the Great Schism in 1054.

Both the Latin and Eastern Churches adopted the hierarchical structure of governance that had characterized Roman imperial administration. Beneath the bishop of Rome, numerous archbishops ruled over the local bishops who governed their dioceses, an imperial unit of administration introduced during the reign of Diocletian (see chapter 10 above). Each diocese was essentially a district that was further subdivided into numerous parishes under the spiritual guidance of the local priest. While in theory, the bishop of Rome ruled over the entire Latin Church, in practice the local autonomy of bishops often proceeded with little interference from Rome before the eleventh century.

During the early Middle Ages, the popes operated not only at the apex of the Latin Church, but they also belonged to the Italian nobility, who fought for control of the papacy in order to gain control over the Church’s increasing wealth and power. In the eighth century Pepin the Short, king of the Franks and father of Charlemagne (discussed below), conquered northern and central Italy from the Lombards and ceded to the papacy a large swath of central Italy. This territory, known as the Donation of Pepin, later became known as “the Papal States.” From this point until the 1800s, the bishop of Rome not only claimed spiritual authority over most of Europe but also claimed secular authority, meaning he ruled as a monarch over the Church’s territory in the central Italian peninsula.

Throughout the early Middle Ages (500-1000), the popes rarely exercised the absolute powers that they later wielded over the Church hierarchy. Instead, the popes claimed authority over doctrine and organization. Centuries later, popes used the claims of their predecessors to argue for their right to control the entire Church hierarchy in an absolute and unchallenged manner.

An important example of an early pope who created such a precedent was Pope Gregory I (r. 590-604), commonly referred to as “Gregory the Great.” Although he had spent several years living in a Benedictine monastery, Gregory proved to be a capable administrator. He hailed from the Roman nobility and was the first pope to have been a monk. Inspired by this experience, he wrote a life of St. Benedict, which recounted the saint’s miracles and unyielding faith in God. Such an account was itself inspiration to the inhabitants of the city of Rome, who faced constant threats from Germanic invaders. Pope Gregory was keenly interested in developing the independence of the papacy from the Roman emperors in Constantinople, and he shrewdly played different Germanic kings in the Italian peninsula against each other by employing his spiritual authority to gain their trust and support. Although he was often preoccupied with events in the Italian peninsula, he sent missionaries into pagan lands, such as Kent in southern Britain, to spread the faith, both out of a genuine desire to save souls and a pragmatic desire to extend his influence across Europe.

Gregory’s authority was not based on military power, nor did most Christians around 600 assume that the bishop of Rome was the spiritual head of the entire Church. Instead, the papacy gradually expanded its authority by creating mutually-beneficial relationships with kings and by overseeing the expansion of Christian missionary work. In the eighth century, the papacy produced a document, later proven to be a forgery, known as the Donation of Constantine in which the Roman emperor Constantine (r. 306-337) vaguely granted the bishop of Rome authority over the western Roman Empire. Over the next several centuries popes pointed to this document as the basis for their wide-ranging claims to spiritual and political authority. Nevertheless, even powerful and assertive popes recognized the limits of their power, and several popes were deposed or even murdered in the midst of political turmoil.

Thus, Christianity spread not because of an all-powerful, highly centralized institution, but because of the dedication, flexibility, and pragmatism of a few capable popes, their missionaries, and their allies among the rulers of Germanic peoples. Missionaries often had official instructions not to battle pagan religious practices, but to subtly integrate them into Christian rituals. It was less important that pagans understood the nuances of Christianity and more important that they accepted the religious authority of the Latin Church. Many pagan practices, words, and traditions survived into the present as a result of the fusion between Christianity and the older Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic religious practices.

This fusion was particularly evident in rituals. In pre-literate societies, rituals conveyed solemnity, meaning, and significance to occasions. They imbued something as routine as the passage of time or as momentous as the transfer of power with meaning and importance. Church leaders maintained elements of pagan customs and traditions in these rituals, such as the celebration of Easter, a name derived from a Germanic goddess of fertility, Ēostre. Local saints even assumed the qualities of pagan deities. They protected cities and ensured the harvest. They facilitated procreation and the perpetuation of the species. Similar to the pagan religions that preceded it, medieval Christianity provided succor to people who were often victims of violence, illness, and natural disasters.

The leaders of the Latin Church understood the need to introduce Christian beliefs and practices gradually into a population that had revered pagan deities for centuries. In a letter to a missionary, Melitus, Pope Gregory advised him to refrain from tearing down pagan temples; he encouraged his missionaries instead to consecrate and reuse them. Likewise, the existing pagan days of sacrifice were to be rededicated to God and the saints. Clearly, the priority was not an attempted purge of pagan culture, but instead a more respectful introduction of Christianity into cultures that had a strong attachment to their ancestors’ traditions. This respect for pagan ancestors encouraged and enabled the fusion of Christian and barbarian cultures throughout most of the Early Middle Ages.

Characteristics of Medieval Christianity

A fundamental belief of medieval Christians was that the Church as an institution was the only path to spiritual salvation. It was much less important that Christians understand any of the details of Christian theology than it was that they participated in Christian worship and received the sacraments administered by the clergy. Because very few members of early medieval societies were literate, they depended on local bishops to relay important information because most Christians could not read about the theological complexities surrounding the virgin birth or the Trinity. The path to salvation relied mostly on participation in Christian rituals, such as baptism, prayers, communion, and eventually confession. However, during the early Middle Ages, the Church had not yet fully defined the necessary rituals for salvation. That level of definition eventually emerged in the High Middle Ages at the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) in the form of the seven sacraments.

Nevertheless, the Latin Church retained and reinforced some of the ancient elements of Christianity:

- Asceticism: The denial of pleasure and comfort was never popular, but those who engaged in prolonged dedication to this principal garnered enormous respect. This element of Christianity likely derived from the ancient Jewish sect of the Essenes and persisted in the practices of monks and some of the Church’s most revered leaders, who later became saints.

- Evangelism: Although Jesus and his apostles were somewhat reticent to spread the faith beyond Jews, the missionary work of St. Paul (in Hebrew, Saul of Tarsus) transformed Christianity dramatically during the first century. Increasingly, Christians had a duty to spread the faith.

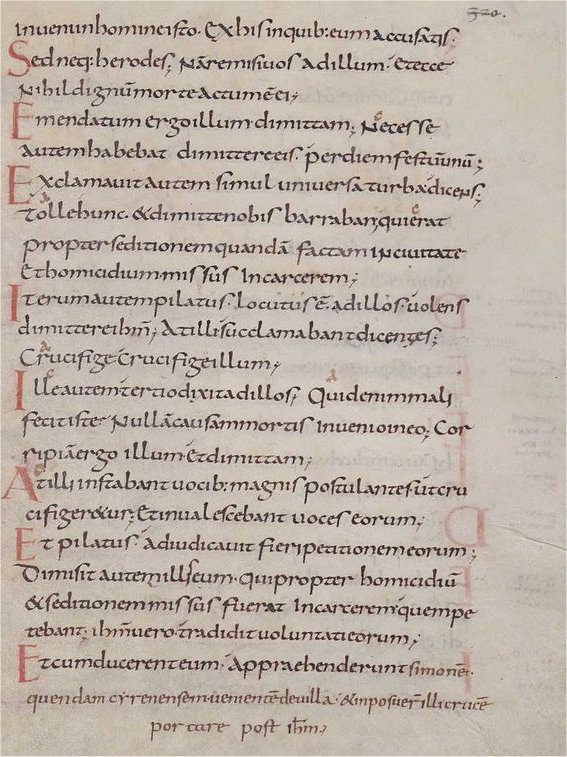

- Book religion: By the time of Jesus, Judaism had a deeply ingrained reverence for writing in general and sacred texts in particular. Because Christianity evolved as a sect of Judaism, its early leaders maintained this attachment. In addition to the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament), by 400 St. Jerome had compiled and translated into Latin the original Greek texts of the New Testament, which included the letters of Paul, the canonical gospels, the Book of Acts, and the Book of Revelation. St. Jerome’s Vulgate Bible became the standard sacred text in the Latin Church until the 1500s.

- Martyrdom: Bloody acts against Christians contributed to the growth of Christianity during the Roman Empire. Martyrs were Christian heroes. Stories of their heroism proliferated, and the definition of martyrdom evolved after Christianity became the imperial religion under the Roman emperor, Theodosius I. Increasingly, ascetics became Christian martyrs along with many Christian missionaries who suffered the traditional martyrs’ fate: violent death.

- Hierarchy: Although Jesus of Nazareth and the early Church promoted equality and the veneration of the poor, by the fourth century Christianity became more like other ancient religions, which supported the existing social hierarchy, ruled by wealthy elites. During the course of the Early and High Middle Ages, the Latin Church strengthened its hierarchical organization and decreased early Christianity’s emphasis on egalitarian principles.

These elements of Christianity combined in various ways during the early Middle Ages. For example, missionaries were evangelical by definition and often practiced asceticism. Most monks maintained vows of obedience to hierarchical authorities and practiced celibacy, and some of them produced elegant Bibles at great cost. Celtic monks often lived in remote places and practiced green martyrdom (described above), but many of them also practiced evangelism as opportunities arose. With all these possibilities for religious expression, bishops oversaw their flocks to ensure both conformity and obedience. However, as the Latin Church evolved during the Middle Ages, the ability of Church leaders to maintain clear lines of authority in the hierarchy came under enormous stress.

The adoption of this complex and rich religion, which had arisen in the cities of the Mediterranean basin, by the illiterate leaders of Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic peoples was often problematic. Some kingdoms underwent apostasy, the reversion to paganism, particularly as some Christian kings lost battles to pagans. Constantine’s claim that God was the source of his victory at the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 had perpetuated the idea that victory in battle reflcted divine grace. Defeat, on the other hand, caused some to doubt or question the faith of their leaders. These setbacks provided obstacles to Christian missionaries. In addition, specific elements of Christianity, such as asceticism and literacy, were notably foreign concepts to barbarian chieftains who took pleasure in raiding. Nevertheless, missionaries demonstrated enormous conviction and persisted in spreading the faith.

One of the tools that aided these missionaries was the vast and growing collection of stories that belonged to the Christian tradition. The lives of saints, also known as hagiography, proliferated in the period 600 to 800, sometimes referred to as the Age of Saints. These stories resembled the heroic tales of warrior heroes conveyed by bards or scops, medieval entertainers and storytellers. Hero worship was deeply embedded in barbarian cultures, and saintly missionaries such as Germanus, Patrick, and Boniface exhibited the type of courage so evident in warrior epics. Undeterred by the prospect of death, their loyalty to God was unconditional, something any warrior chieftain could appreciate. In hagiographical narratives, the heroes calmed storms, averted natural disasters, healed the sick, and even raised the dead. In one case, St. Genevieve (419-512) convinced the people of Paris to pray collectively in order to avoid defeat at the hands of the Huns. The Huns bypassed the city, and Genevieve became the Parisian patron saint. In this fashion, tales of saints reinforced loyalty to the faith by celebrating commonly held values such as faith, hope, and charity.

Christianity also proliferated because it strengthened a sense of community with its many rituals, festivals, and feast days. In monasteries, monks gathered together in prayer five times a day. They dressed alike, prayed together, and shared meals. Outside of monasteries, people celebrated feast days and heard stories of heroic saints as a community. They gathered to receive communion, and some watched as their kings received the biblical chrism, a ceremony in which a bishop anointed temporal kings as God’s chosen rulers. These rituals promoted and fostered a sense of loyalty, community, collective identity. This aspect of the religion is why the term “ecclesiastical,” which derived from the Greek word for community, became synonymous with religion. Religion promoted a sense of common identity.

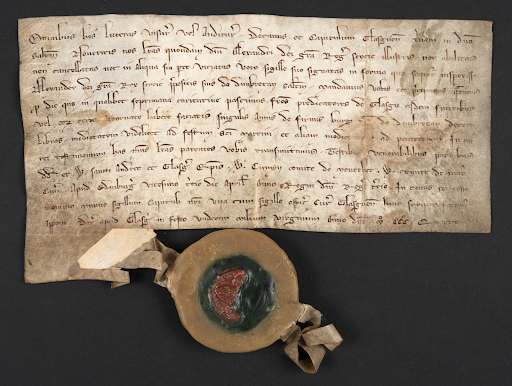

In addition to this social cohesion, Christianity also promoted political unity, but very gradually. Over the course of centuries the beliefs and practices of Christianity strengthened royal power. Kings often relied on literate clergy to administer their kingdoms. They employed scribes to keep track of tribute money, which later evolved into taxation. They also learned the power of written commands, which reduced the need to travel constantly across their kingdoms to exert their will. Instead, they established a hierarchy of administrators in local districts, much as the Church had done. They produced legal codes and recorded histories of their people and their successes over their enemies. Monarchs began to assemble their own collection of stories, which encouraged collective actions against commonly acknowledged foes. Gradually, some monarchs embraced charters as a way to document land transfers and minimize the disruptive disputes that threatened political cohesion.

Land was the ultimate source of virtually all wealth in these mostly agricultural societies, and as such, its transfer often provoked conflict as disagreements arose over the details of an agreement. Because charters could document precise terms of a land transfer, they offered the prospect of reducing the conflicts that plagued early medieval societies. However, charters did not become widely accepted for settling disputes over land until the High or even Late Middle Ages. The Church routinely falsified charters, and most members of the warrior aristocracy remained illiterate and distrustful of writing. Nevertheless, writing gradually strengthened the centralized power of kings at the expense of local nobles, and the Church leaders were instrumental in promoting the use of charters.

The Church’s role in promoting centralization of its own power at the expense of the nobility arose during the tenth century in the monastic reform movement. Led by the monks at Cluny in Burgundy, adherents of the movement called for more centralized control of monasteries. Since the 600s, nobles had established monasteries for a variety of purposes, including the salvation of their souls and comfort of their offspring. These nobles considered the monasteries to be part of their familial patrimony or landholdings. However, with little supervision from the Church, the monks at these monasteries often failed to follow monastic rules related to celibacy, obedience, and hard work. In response to this lax supervision of monastic rules, the monks at Cluny gradually established themselves as the mother house of the many hundreds of monasteries that had proliferated over hundreds of years. They argued that the only way to ensure monastic purity was to wrest control of these lands from the nobles and place them in the hands of the Church. Not everyone agreed, and the reform movement sparked violent disagreements for over 100 years.

Monastic reform eventually led to general Church reform, which included enforced celibacy for all clergy including priests and bishops. Both sets of reforms had a destabilizing effect on political authority across Europe during the tenth and eleventh centuries because they threatened traditional assumptions about the control of land. Monastic and Church reforms fundamentally altered the distribution of wealth and therefore the balance of power. Gradually, these reforms increased the wealth and power of the Church, which became the most powerful rival to several kings at various points during the High Middle Ages.

Early Medieval Politics

While most Europeans came to share a religious identity by the eleventh century, Europe was still fragmented politically. The numerous Germanic tribes that had dismantled the western Roman Empire formed the nucleus of the early political units of western Christendom. The Germanic peoples themselves had started as minorities, ruling over formerly Romanized and Celtic subjects, especially in the kingdoms of the Franks, the Burgundians, and the Lombards. In areas that had been part of the empire, they were often able to utilize the remnants of the Roman bureaucracy and relied on its officials and laws when ruling their subjects, but they also had their own traditions of Germanic law based on clan membership. In short, the legal orders of the Early Middle Ages were not universal or systematic in their treatment of transgressions. Different laws applied to different people.

The so-called “feudal” laws applied specifically to the nobility or holders of fiefs (feodum in Latin). Feudal laws were based on codes of honor and reciprocity. In the original Germanic codes each free person or warrior was obliged to support his (it was patriarchal) clan above all else, and an attack on an individual became an issue for the entire kinship group. Any dishonor had to be answered by an equivalent dishonor, most often meeting insult with violence. Likewise, the most powerful kings arose because of clan dominance, with the king being the head of the most powerful clan rather than an elected official or even necessarily a hereditary monarch who transcended clan lines. This unregulated, traditional, and violence-based system of the competition for power often produced feuds, the interfamilial and sometimes intrafamilial infighting that destabilized European politics during much of the Early Middle Ages.

Gradually, the Germanic warrior elites mixed with their Latin or Celtic subjects to the point that cultural distinctions became less prominent. Likewise, Roman law faded away as a very complex web of rights and privileges emerged. Granted to warrior clans and others by monarchs, these feudal laws were intended to ensure the loyalty of their subjects. Thus, clan loyalty became less important over the centuries. However, it still exercised considerable sway through much of the Early Middle Ages. In the process, medieval politics evolved over time into a more hierarchical, class-based structure in which kings, lords, and Church leaders ruled over the vast majority of the population: peasants.

In some parts of Europe, especially in the territories of the Franks, the relationship between lords and kings evolved into a formalized system of mutual protection. Lords accepted oaths of personal loyalty, called a “pledge of fealty,” from other free men called “vassals.” In return for vassals’ support in war, the lord offered them protection and land-grants, called “fiefs.” Each vassal had the right to extract wealth from his land in the form of fees and taxes on peasants who inhabited the fief or manor. The lord could then use this wealth to procure horses, armor, and weapons in addition to the needs of his household and retainers. In general, vassals did not have to pay taxes or tribute money to their lords. Instead, the lord expected them to perform military service. Likewise, the Church itself became an increasingly wealthy and powerful landowner, and Church holdings were frequently tax-exempt. However, kings expected bishops to provide them with services in administrative capacities: overseeing revenues, presiding as judges, recruiting capable scribes, and enforcing orthodoxy. These bishops were lords of extensive estates, and every king worked to recruit bishops who would serve them ably. Monarchs relied on these Church leaders to administer their kingdoms.

This system based on personal bonds withered as generations passed.

Sometimes royal vassals became less attached to the kings’ sons than they had been to the fathers. This form of political organization, based on personal loyalty, was fundamentally unstable and arose because of the absence of other, more effective forms of government and the constant threat of violence posed by raiders. The feudal order was never as neat and tidy in practice as it was in theory; many vassals were lords of their own vassals, with the king simply being a remote entity with weak legal claims. In turn, the problem for royal authority was that some kings had vassals who had more land, wealth, and power than they did; it was fairly common for powerful nobles to wage war against their king. It would take centuries before the monarchs of Europe consolidated enough wealth and power to dominate their nobles, and it rarely happened during the Early Middle Ages.

One method that kings used to punish unruly vassals was simply to visit and eat them out of house and home. The traditions of hospitality required vassals to welcome, feed, and entertain their king for as long as he felt like staying. Kings and queens expected respect and deference, but conspicuously rare during the Early Middle Ages was any widespread recognition of what was later called the “Divine Right” of monarchs to rule. From the perspective of the noble and clerical classes in the Early Middle Ages, the monarch had to hold on to power through force of arms and personal charisma, not on empty claims about being on the throne because of God’s will. In other words, laws and legal rights had much less influence than one might assume.

Unsurprisingly, there are many instances in early medieval European history when a powerful lord simply usurped the throne, defeated the former king’s forces, and became the new king. Ultimately, early medieval politics involved widespread violence and treachery. Pledges of loyalty between lords and vassals provided a weak framework for political stability. In a legal code produced around 890, Alfred the Great of England recognized the weaknesses associated with loyalty oaths, and the very first law of his legal code addressed this issue. While the law itself may not have been that effective, he emphasized to his nobles that he was keenly aware of the issue and its importance to political stability. Meanwhile, the Church encouraged lords to live in accordance with Christian virtue. However, the nobility defined itself as “those who fight,” meaning they were warriors first and foremost. Thus, all too often politics was synonymous with armed struggle throughout much of the Middle Ages.

Perhaps the most conspicuous failure of the practice of oaths of loyalty to sustain political stability occurred in Francia, the western remnants of the Carolingian or Frankish Empire (described in detail below) during the 900s. At this point the king’s direct authority had deteriorated to include the areas around the Isle de France near Paris. Other areas of Francia were under the nominal control of counts, but real control fell into the hands of castellans, knights who lived in wooden fortresses, scattered across the countryside. They periodically rode from these rudimentary castles and plundered peasants, merchants, monks, and anyone who could sustain their needs. Consequently, commerce declined significantly, as the risks of travel heightened. As we will see in the next section, political instability in Francia was more pronounced than stability, following the reign of Charlemagne.

In response to the epidemic of violence that arose in Francia during the 800s and 900s, communities became desperate for a solution, especially in the central and southern region known as Aquitaine, where little centralized authority existed. In 989 at Charroux in Aquitaine, a local convocation of clergy proclaimed the Peace of God, based on centuries of Church proclamations aimed at limiting violence. Such proclamations gradually spread across much of Francia. The primary purpose of these measures was to limit violence against peasants, priests, and other non-combatants. However, the Church too relied on oaths, sometimes sworn on the relics of saints, to secure enforcement. By the eleventh century, another council at Toulouse in southern France proclaimed the Truce of God in 1027. This proclamation sought to disallow violence on weekends and feast days. Neither the Peace of God nor the Truce of God proved particularly effective, and violence remained an epidemic in much of Francia well into the High Middle Ages.

The Frankish Empire

The former Roman province of Gaul eventually became the heartland of present-day France, ruled in the aftermath of the fall of Rome by the Franks, a powerful Germanic people who invaded Gaul from the eastern shore of the Rhine River as Roman power crumbled in the mid-400s. However, the Franks’ relationships with the Romans and later with the Latin Church were complicated. Some Franks fought with the Romans against the Huns at the Battle of Chalons in 451, while others fought on the side of Attila. After that battle, one of the dominant clans, the descendants of Merovech under the leadership of Childeric I, established his principal seat of power first at Tournai in modern-day Belgium and then at Paris after consolidating his control over rival Frankish leaders. Childeric I essentially established the Franks’ Merovingian dynasty, named after his father.

His son, Clovis I (r. 481 – 511), was the first to unite all the Franks and begin the process of creating a lasting kingdom named after them: Francia, later France. Clovis murdered rivals both in other clans and within his own family. He then expanded his territories and defeated the last remnants of Roman and Visigothic powers in southern Gaul by the end of the fifth century. Around 496 CE Clovis and his warband converted to Latin Christianity, the religion of Clovis’s wife, Clotilde.

Queens were often instrumental in the conversion to Latin Christianity. This influence, referred to as “domestic proselytization,” was a conscious strategy of Latin Church leaders, who encouraged queens to exert their influence on their monarchical spouses. In this case, Clovis’s conversion to Roman Christianity had practical benefits: he planned to attack the Visigoths in southern Gaul. The Visigoths were an Arian Christian (see chapter 10) minority who ruled over a Latin Christian population. By converting to Latin Christianity, Clovis ensured that the Latin Christian subjects of the Visigoths were likely to welcome him as a liberator rather than a foreign invader. He was proved right, and by 507 the Franks controlled almost all of Gaul, including formerly-Gothic territories in the Mediterranean region.

By the seventh century, the Merovingians expanded their territories across the Rhine into areas that had not been part of the Roman Empire and across the Alps into the northern Italian peninsula. Their grasp over these territories was never absolute and varied according to the strength and charisma of individual kings. Meanwhile, the sons of Frankish kings typically divided their territory into equal parts, a tradition known as partible inheritance. Gradually, Francia became an assemblage of four kingdoms: Austrasia in the northeast, Neustria in the northwest, Burgundy in the southeast, and Aquitaine in the southwest. Infighting between the kingdoms was frequent, and consequently, centralized control of the Merovingian empire was tenuous. In addition, the kings themselves increasingly relied on officials called “mayors of the palace” to command troops and lead the Franks into battle. Some Merovingian kings became ceremonial figureheads rather than warband leaders, a change that further weakened their control.

Although the Merovingians retained monarchical power for two hundred years, they became relatively weak and ineffectual by the early 700s. Meanwhile another clan, the Pippinids (later Carolingians), the family of Pepin the Short, demonstrated their leadership as military commanders. They were the mayors of the palace in Austrasia, but they ran the military and political affairs both of Austrasia and of Neustria by the early 700s. One of them, Charles Martel, defeated the invading Muslim armies at the Battle of Tours (also referred to as the Battle of Poitiers) in 732. Soon afterwards, Charles Martel’s son, Pepin, seized power from the Merovingians in a coup, one later ratified by the pope in Rome. This act strengthened the legitimacy of the dynastic shift and established the Carolingians as the rulers of the Frankish Empire.

Only the first few kings in the Carolingian dynasty of the Franks were particularly capable. When Pepin seized control in 750, he was merely assuming the legal status that his clan had already controlled behind the scenes for years. The problem facing the Franks was that Frankish tradition stipulated that sons had equal rights of inheritance after the death of the father. Thus, with every generation, a family’s holdings could be split into separate, smaller pieces. Over time, this custom could reduce a large and powerful kingdom into a large number of small, weak ones, and it often increased intrafamilial violence. When Pepin died in 768, his sons Charlemagne and Carloman each inherited half of the kingdom. When Carloman died a few years later, Charlemagne ignored the right of Carloman’s sons to inherit his land and seized it all; his nephews were subsequently murdered.

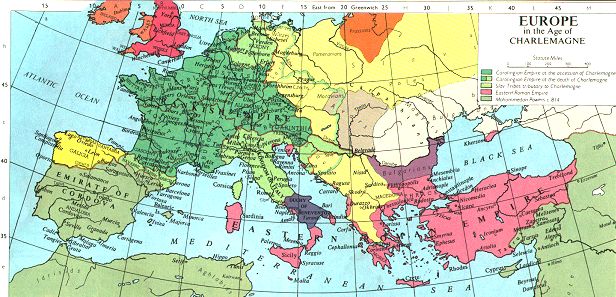

Charlemagne (r. 768 – 814) ruled over the largest territory of any European king or emperor in the early Middle Ages. He waged constant wars during his long reign (lasting over 40 years) in the name of converting pagan Germans in Saxony to Latin Christianity. His conquests inspired the notion that the Roman Empire had reemerged in large parts of western Europe. By the 1200s, part of his territory became known officially as the Holy Roman Empire, an expansive state that was nominally controlled by a single emperor with the support of the papacy in Rome. This myth of a resurrected empire was enduring in its appeal. However, Charlemagne was the only emperor to rule this territory effectively as a united state, and the papacy often opposed his successors. Nevertheless, several Holy Roman Emperors exercised considerable power over the empire until the end of the Thirty Years War in 1648, and the empire itself remained a legal fiction until 1806 when Napoleon permanently discarded it.

Charlemagne distinguished himself not only by the extent of the territories that he conquered but also by his insistence that he rule those territories as their legitimate king. In 773, at the request of the pope, Charlemagne invaded the northern Italian kingdom of the Lombards, the Germanic tribe that had expelled Byzantine forces earlier. When Charlemagne conquered them a year later, he declared himself King of the Lombards rather than forcing a new Lombard ruler to become a vassal and pay tribute. This was un-traditional for a Germanic ruler to proclaim himself king of a different people. How could Charlemagne be “King of the Lombards,” since the Lombards were a separate clan and kingdom? This bold move on Charlemagne’s part established the answer and an important precedent: kingship could pass to a different clan or even kingdom itself depending on the political circumstances. Charlemagne clearly embraced an imperial vision: the Franks were the rulers over an amalgam of Germanic and Slavic peoples.

Charlemagne distinguished himself not only by the extent of the territories that he conquered but also by his insistence that he rule those territories as their legitimate king. In 773, at the request of the pope, Charlemagne invaded the northern Italian kingdom of the Lombards, the Germanic tribe that had expelled Byzantine forces earlier. When Charlemagne conquered them a year later, he declared himself King of the Lombards rather than forcing a new Lombard ruler to become a vassal and pay tribute. This was un-traditional for a Germanic ruler to proclaim himself king of a different people. How could Charlemagne be “King of the Lombards,” since the Lombards were a separate clan and kingdom? This bold move on Charlemagne’s part established the answer and an important precedent: kingship could pass to a different clan or even kingdom itself depending on the political circumstances. Charlemagne clearly embraced an imperial vision: the Franks were the rulers over an amalgam of Germanic and Slavic peoples.

On Christmas day in 800, the Bishop of Rome, Pope Leo III, crowned Charlemagne “Emperor of the Romans.” Although historians often claim that Charlemagne’s crowning was a surprise or even unwanted, the pope’s recognition of Charlemagne imparted a level of prestige, at least in Italy, and suggested a return to the Pax Romana. It also established a precedent that ultimately rendered the Frankish/German emperors dependent on papal recognition for their authority. In other words, the elevation of Charlemagne as the Emperor of the Romans also increased the power of the papacy, which was mired in the political rivalries of central Italy. As the papacy became more powerful in subsequent centuries, the tensions between emperors and popes escalated, sometimes into civil wars that involved much of the northern Italian peninsula and the empire north of the Alps.

Charlemagne’s empire did not exhibit the organizational effectiveness that characterized ancient Rome. Although Charlemagne developed a rudimentary bureaucracy with written orders emanating from his entourage to various localities via missi dominici, meaning envoys of the lord king, it often lacked the literary competence to function effectively. In addition, his armies paled in comparison to the Roman legions in terms of size, logistical support, and training. Similar to the majority of Germanic rulers, he spent most of his reign traveling around his empire with his armies, while waging wars and issuing decrees. Medieval historians refer to this form of governance as “peripatetic kingship,” meaning the king had to travel around a lot, which was a sign of a weak administrative structure. Charlemagne recognized this weakness and initiated numerous reforms.

In imitation of King Offa across the English Channel, Charlemagne reformed the currency by minting high quality silver pennies (pictured below), called deniers. He realized that gold was notoriously scarce, which limited its usefulness as a currency. By contrast, silver was more plentiful and therefore practical for widespread use. Consequently, regional trade improved with the introduction of a more practical currency. Meanwhile, he organized large royal estates that produced commodities for burgeoning markets and he sustained a modicum of peace spread across his vast dominions. Long distance trade flourished as the empire exported slaves, mostly war captives from Slavic eastern Europe to Muslims on the Iberian peninsula and in North Africa. All of these economic initiatives strengthened the royal treasury and enabled patronage of intellectual activities. His initiatives teetered on the precipice of civilization and reflected the exploitation and the production of amenities that came with it. However, it failed to produce the necessary urban infrastructure that has traditionally accompanied civilizations.

Recognizing the weakness of imperial administration, Charlemagne channeled growing tax revenues into a determined effort to improve literacy and learning within his empire. Thirteen years into his reign (781), he recruited the scholar Alcuin from northern Britain (Northumbria) to his court in Aachen, where Alcuin served as the master of the palace school. Over the next four decades, scribes preserved ancient Roman documents and wrote royal decrees. They recorded legal proceedings and kept records of the administration of royal estates. Historians often refer to this growth of literary production, which accompanied artistic and architectural achievements, as the “Carolingian Renaissance.” Unlike the Italian Renaissance of the 1300s and 1400s, it did not extend to widespread literacy among the middle class. In fact, there was only a very small percentage of the population in his empire whom we might label “middle class.” Instead, the Carolingian Renaissance was mostly confined to royal and monastic circles.

During the Carolingian Renaissance significant improvements in handwriting occurred. Scribes imitated the Roman practice of large, clear letters that had distinct separations. They inserted more spacing between words and punctuation, including question marks and periods, to separate sentences. Scribes increasingly introduced the division between upper and lower-case letters and the practice of starting sentences with a capital letter, a minor improvement that facilitated comprehension of writing. While all of these changes seem fairly minor, their impact was significant because they facilitated the growth of literacy and comprehension of written commands, judicial proceedings, and the intellectual heritage of ancient Rome. This new form of handwriting, known as Carolingian minuscule, developed during the Carolingian Renaissance. Punctuation, capitalization, more pronounced spaces between words, and more clearly rendered letters became standard and facilitated the exchange of ideas through writing.

These reforms in writing also enabled one of Charlemagne’s other initiatives: the reform of the Church. He insisted on a strict hierarchy of archbishops to supervise bishops who, in turn, supervised priests. He sponsored the education of priests and the creation of libraries. To be effective at conveying the teachings of Christianity, priests had to be literate, and they also needed to have accurate Bibles in their possession. He had flawed versions of the Vulgate Bible (the Latin Bible) corrected and he revived Greco-Roman disciplines, such as rhetoric, logic, and astronomy, that had fallen into disuse. An educated clergy was essential for increasing the prestige of the Church and the emperor. As we will see in the following chapter on the High Middle Ages, the Carolingian educational and religious reforms laid the foundation for significant changes in theological studies across Western Europe.

Another element of Charlemagne’s reforms included the reorganization of his empire into counties, ruled by (appropriately enough) counts. He appointed trusted military officials and some literate commoners to rule lands where they had little or no social connections. This tactic of employing men deemed as foreigners to administer counties minimized the risk of these men drawing followers of their own and ensuring some degree of impartiality in justice because they were not tied to local clan networks. He protected his borders with marches, lands ruled by margraves who were military leaders ordered to defend the empire from foreign invasion. He established a group of officials who traveled across the empire inspecting the counties and marches to ensure loyalty to the crown. Despite all of his efforts, rebellions against his rule were frequent, and Charlemagne waged war against rebellious subjects to re-establish control on several occasions.

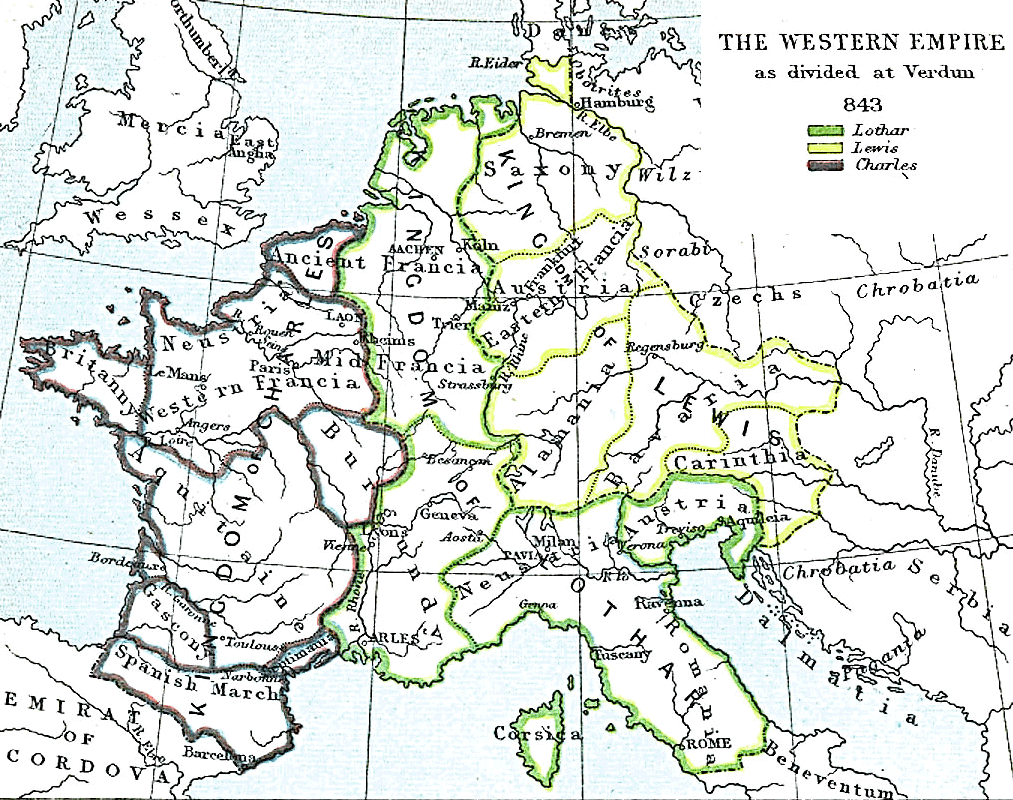

Despite the significant reforms introduced during Charlemagne’s long reign, the Carolingian dynasty lasted for an even shorter period than had the Merovingian. The problem, again, was the Frankish succession laws related to partible inheritance, which encouraged the division of kingdoms and the infighting that plagued the quest for political stability during the Early Middle Ages. Following his death in 814, many of his reforms lost traction. Lacking a strong unifying story, such as a history of his people, his empire lacked cohesion, and without an effective charismatic leader to suppress revolts, regions rebelled soon after Charlemagne’s reign. The origin of “Germany” (not politically united until 1871, over a thousand years after Charlemagne’s lifetime) was East Francia, the kingdom that Charlemagne’s son Louis the Pious left to his son, Louis the German. A different line, not directly descended from the Carolingians, eventually ruled East Francia by the 900s (see next chapter). Its king, Otto the Great, was crowned emperor in 962 by the Pope, thereby cementing the idea of the Holy Roman Empire even after Charlemagne’s bloodline no longer ruled it.

The Early English State

Around 400 CE, the Romans began withdrawing from Britain, where they had maintained three to five legions since the middle of the first century CE. In the fifth century the Romans redeployed their legions to meet the growing threat of instability and invasion at the imperial borders along the Rhine and Danube rivers. Britain had always been an imperial frontier, with too few Romans to completely settle and organize it. During the 400s and 500s Germanic warriors from Saxony, Frisia, modern-day Denmark (land of the Angles), and even Scandinavia raided, invaded, migrated, and settled in the southern half of the island of Britain. By at least the 700s and likely earlier, this area became known as the “land of the Angles” or England.

These pagan Germanic peoples fought the Celtic Britons, who had inhabited the island in large numbers for approximately 1500 years. By the 400s these Britons identified as Christians. Fleeing the Germanic invaders, the Celtic refugees maintained control of the western parts of the island in modern-day Cornwall, Wales, and Scotland. Some fled as far away as Brittany across the Channel. Roman culture all but vanished as Germanic clans fought for control of various parts of the island. Consequently, the kingdoms established by the Germanic invaders in southern Britain became some of the most thoroughly de-Romanized of the old Roman provinces in the west.

Around 597, King Aethelberht, who ruled over Kent in the southeastern corner of the island of Britain, received Christian missionaries from Rome. His wife, Bertha, a Christian Merovingian princess, exercised her influence on her husband, as her daughter and granddaughter later did on their husbands, to embrace the teachings of the Latin Church. Similar to the conversion of the Merovingian king, Clovis, a century earlier, Aethelberht’s decision to embrace the teachings of the Latin Church accompanied the conversion of hundreds or even thousands of his warriors. The Latin Church practiced a top-down strategy of conversions: convert the king, and the kingdom will follow. Although this approach was highly effective in the long run, sometimes early English kingdoms experienced apostasy, the return to pagan practices, as new kings rejected their predecessors’ conversions. Slowly, with much determined effort by dedicated missionaries, all of the previously pagan Germanic kingdoms in Britain converted by the second half of the 600s.

Aside from Roman missionaries, Celtic missionaries had established a monastery at Iona off the East coast of Scotland by 565. By the early 600s, they were successfully converting Celtic and English kings. In the 630s they established a monastery at Lindisfarne on the West Coast in the kingdom of Northumbria. These Celtic missionary-monks solidified the Northumbria kings’ previously tenuous attachment to Christianity. Northumbria had been one of the most violent and politically unstable kingdoms of the early English. By the 640s that infighting showed signs of subsiding under the brutal but effective reign of King Oswy (642-670) Oswy defeated one of the last powerful pagan kings, Penda of Mericia, in 655. Afterwards, Northumbria enjoyed a period of relative peace and dominance among other English kingdoms during the final 15 years of Oswy’s reign, and Celtic monks were primarily responsible for ensuring that Northumbria’s kings remained in the Christian fold.

One issue that threatened to divide the Northumbrians centered on the type of Christianity the kingdom would practice. Although raised in a Celtic Christian tradition (described in the section on the Celts above), King Oswy had married the granddaughter of Bertha and Aethelberht of Kent, Eanfled. She followed Latin Christian teachings that her grandparents had introduced into Kent around 600. Meanwhile under the influence of Celtic missionaries, led by the saintly bishop, Aidan (c. 590-651), Celtic Christian practices had become the norm in Northumbria. While the differences between the two forms of Christianity might seem insignificant to us today, they mattered for a king who sought religious unity in his kingdom. Not only was the queen loyal to the Church of Rome, but so was the heir apparent. Following the death of Aidan in 651, disagreements between Celtic and Roman churchmen about the timing of Easter celebrations intensified in Northumbria. The differences in the dates could vary between the Roman and Celtic calendars by as much as a week.

One of the main attractions of Christianity to Germanic kings was its uniformity, but the divisions between the Celtic and the Latin Church leaders on a number of issues, including the nature of religious authority, threatened to divide the Northumbrians. Whereas Celtic Christians often recognized the more localized authority of abbots, Roman Christians adhered to the hierarchy of the Church with the pope at its apex. At Oswy’s request, the clergy convened a small council, known as a synod, of Church leaders and royal followers to resolve the dispute at Whitby Abbey in 664. Oswy’s decision to embrace Latin Christianity at the Synod of Whitby had long-term implications for the English attachment to the Church of Rome. It weakened the independence of the Celtic Christians, who gradually adopted Roman practices and accepted the authority of the Bishop of Rome. Consequently, the Christianity practiced in the British Isles slowly became more aligned with Continental customs, associated with the Latin Church, and this uniformity facilitated marriage alliances and treaties among royal families.

In the decades that followed the Synod of Whitby, the English, and the Northumbrians in particular, expanded their literary production. Similar to the Carolingian Renaissance, which started 100 years later, the Northumbrian Renaissance featured the achievements of monks and religious scholars. They produced Bibles of exquisite artistry at considerable expense. They wrote legends of saints’ lives, hagiography, and recounted the history of their own conversion to Christianity. They sent missionaries to convert the Saxons and Frisians on the Continent. They introduced charters for land transfers. And they educated some of the most renowned scholars in Europe, such as Alcuin, Charlemagne’s master of the palace school.