15

Introduction

Europe developed the defining features of a civilization during the High Middle Ages (1000-1300) due to a variety of factors, including population growth, the exportation of violence, recovery of ancient texts, and the development of a market-based economy. Situated between the Early Middle Ages and the Late Middle Ages, the High Middle Ages is sometimes referred to as the Central Middle Ages. However, we are using the terminology of the High Middle Ages because the period included significant cultural developments that became integral to European civilization and its collective identity. It was “high” in the sense of reaching an apex in population growth, socioeconomic evolution, and cultural expansion. This chapter will focus on those features of Europe, while addressing significant political patterns in the Holy Roman Empire, England, and to a lesser degree, France.

During this period, the population likely tripled, the number and size of cities increased, trade networks became more reliable, and literacy spread as rulers sought the services of administrators, scribes, storytellers, and propagandists. This proliferation of literacy was particularly important for the study of history, which relies on documents to make sense of the past. As literacy increased, Europeans produced more documents. Consequently, we have much more informed insights into the thoughts, behavior patterns, motivations, and objectives of Europe’s elites, who often oversaw document production. Although we would very much like to know more about the less literate members of society, our written sources have remained heavily biased toward understanding Europe’s warrior aristocracy, Church leaders, and the scribes who worked for them.

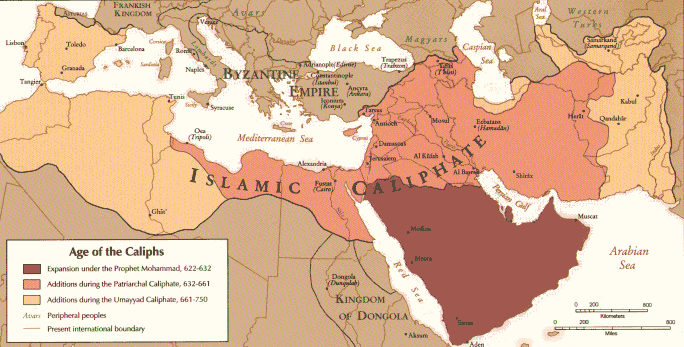

These fundamental changes altered the economic and cultural landscape of Europe. Rulers extended the lands under their control. First and foremost, they successfully fended off invasions. In fact, they expanded the dominions of European culture by reconquering much of the Iberian peninsula from Muslims who had cultivated a vibrant culture there since the 700s; likewise, they uprooted Byzantine and Muslim control of southern Italy and Sicily. They settled much of eastern Europe by campaigning against allegedly pagan Slavs, and they established colonies overseas, most notably in the crusader states in the Levant and on islands across the Mediterranean. In short, during the High Middle Ages Europeans transformed from being the objects of invasions to being the invaders of other lands. The areas controlled by Europeans were growing territorially and economically.

As these conquests proceeded, the peasants drained swamps, cleared forests, and brought more land under cultivation. Agricultural production, population, and trade grew, as did tax revenues. The Church and the secular rulers across Europe invested their growing wealth in the construction of elaborate Gothic cathedrals and sophisticated castles. These undertakings enhanced the power and prestige of the elites, who became increasingly confident in divine support of their missions. They hired legions of administrators, educated in a growing number of universities, where knowledge of Greco-Roman works became more widespread.

This increasing familiarity with the achievements and knowledge of the ancients arose, in part, from increased interaction with the Islamic and Byzantine civilizations to the south and to the east. Some scholars traveled over the Pyrenees to access the highly literate Muslim culture of al-Andulus in the Iberian peninsula, while others traveled to and from Constantinople to bring copies of ancient works back to Latin Christian Europe. Scholars introduced Aristotelian texts to universities and pursued the development of scholasticism. The fundamental assumption of scholastic discourse was that ancient authors, such as Aristotle, were worthy of serious study. However, the ancients often contradicted each other, on a variety of topics including philosophy, astronomy, and their assessment of human nature, supposedly because they lacked the insights of Christian teachings. Therefore, scholastics deemed it necessary and fruitful to apply logic and Christian wisdom to resolve these apparent contradictions. Both Jews and Muslims had undertaken similar initiatives, based on their own religious orientations, in previous centuries.

European scholars had traveled to Muslim and Byzantine centers of learning since at least the mid-tenth century. However, the rate of transmission of ancient writings increased during the eleventh and especially during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, partly as a byproduct of the establishment of crusader states in the Levant. Even before the crusades, western Europeans had gained control of southern Italy, Sicily, and the northern half of the Iberian peninsula in the late 1000s. As the fighting eventually abated, these conquests strengthened commercial and social interactions with Byzantines and Muslims. Trade and diplomacy nourished cultural interaction, and the Latin Christian scholars expressed admiration for the intellectual abilities of their religious rivals: Eastern Christians, Jews, and Muslims.

Social interactions with the Muslims were especially beneficial for the Latin Christians partly because the territory under Islamic control spanned from the Iberian peninsula to India. The enormity of this territory, with more landmass than the Roman Empire at its height, facilitated long-distance trade and the transmission of ideas, technologies, and social practices. Sometimes these Islamic territories functioned as a conduit for the transmission of science, learning, and technology from China. In some cases, such as the pointed arch and the construction of rounded towers, Europeans were more willing to accept Islamic technology and learning. In others, however, Europeans rejected new ideas, as was the case with paper-making; Europeans refused to adopt paper for centuries, viewing it as inferior to animal skins (vellum) for book production. In still other cases, we do not know precisely how much influence Islamic knowledge had on European practices.

One of the less understood cases involves Islamic knowledge of agricultural practices, agronomy. During the High Middle Ages the Muslim understanding of crop rotation, irrigation, and the construction of pleasure gardens surpassed the most advanced practices in western Europe. Although Muslims in al-Andalus introduced crops, including chickpeas, lentils, lemons, rice, and spinach, from India and as far away as China by the tenth century, many of these crops probably did not make their way north of the Pyrenees for centuries. The Europeans’ distrust of Muslims combined with the conservatism of European peasants further inhibited the ready adoption of advanced agricultural practices beyond Castile, Leon, Aragon, and Portugal. In addition, many Muslim texts about herbs, crops, irrigation, and soil remained in Arabic, untranslated into Latin until the thirteenth century or even later. Knowledge of these advanced techniques traveled primarily through observation and through word of mouth. Consequently, the Muslim agronomy diffused very slowly to the rest of Europe, over the course of several centuries, primarily from the Muslim-occupied Iberian peninsula.

Economic Growth

The economy of medieval Europe was pre-industrial; approximately 90% of all economic activity revolved around agriculture: the production of food and raw materials for clothing. In such an economy, land was the primary means for generating wealth. The lords of manors, both secular and ecclesiastical, extracted payments from residents on their lands. Free peasants typically paid an annual rent to the lord who owned the land they occupied. By contrast, serfs were often subject to a number of fees for the right to inherit the right to occupy land, for the lord’s permission to marry, and for a variety of seemingly random assessments called tallage. This last sort of fee was particularly odious because lords often levied it at will. In addition, lords routinely required both peasants and serfs to use the lord’s mill in order to profit from their need to mill grain. In short, the wealth generation that occurred during the High Middle Ages accumulated mostly into the hands both of the warrior aristocracy and of the Church, both of whom were the lord of the manors.

In some principalities and kingdoms of Europe, the Church controlled over half of the land. In other areas, the number was closer to 20%. Still, the Church’s landholdings were substantial. The Church also had other means for generating revenue. A system of taxation, known as the tithe, extracted approximately 10% of the harvest every year from peasants who lived on the lands of the aristocracy. Eventually monarchs also taxed the commoners, usually in the context of declaring wars. However, the Church led the way in terms of devising an annual system for the extraction of Europe’s growing prosperity.

That prosperity was due to a combination of factors, including naturally occurring climate change, improvements in agricultural technology, and changing social practices. The northern Atlantic climate underwent a warming trend that lasted from approximately 900 to 1300 CE. Although the warming was nowhere near as pronounced as the climate change experienced globally in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, it was enough to lengthen the growing season slightly in Northern Europe. The warming lengthened the growing season and reduce the likelihood of crop failure.

The improvements in agricultural technology occurred slowly and unevenly. Early medieval peasants had literally scratched away at the soil with light plows, usually drawn by oxen or donkeys. These scratch plows resembled those used in ancient Rome: the weight of the plow was carried on a pole that went across the animal’s neck. Thus, if the load was too heavy, the animal would suffocate. In turn, that meant that only relatively soft soils could be farmed, limiting the amount of land that could be made arable. Europe north of the Alps mostly had heavy soil with lots of clay. The scratch plow did not work well there.

By 1100 a new kind of collar for horses and oxen became common across Europe. It rested on the shoulders of the animal and thus allowed it to draw much heavier loads, enabling the use of heavier plows. The Latin word for such plows was a carruca: a plow capable of digging deeply into the soil and turning it over, bringing air into the topsoil and refreshing its mineral and nutrient content. We commonly refer to such plows as the moldboard or heavy-wheeled plow. Simultaneously, iron horseshoes became increasingly common, which dramatically increased the ability of horses to pull heavier loads. Further complementing these improvements was the widespread use of iron plowshares, the leading edge of the plow, which turned over the soil with greater efficiency. Although individually these advancements were fairly minor, collectively they had a pronounced impact on agricultural productivity.

The heavy-wheeled plow was much more effective, especially in Europe north of the Alps, where the soil tended to have more humus and clay and less sand. The plow was especially effective because it went deep into the soil, where the nutrients often were, and it also removed the weeds at the surface as the earlier plow had done. The old scratch plow, which had been developed in the Mediterranean basin, where sandy soils predominated, was not really suitable for the heavy soils of northern Europe. The heavier plow first appeared in China by about 200 BCE, and such plows were known in the Roman Empire. However, it was not until the late tenth century that use of the heavy-wheeled plow became common in Europe. The reasons for the slow adoption were manifold. First, peasants tended to be very traditional. A small change in agricultural practices could mean starvation if those practices proved unworkable. In addition, peasant communities often required consensus because they worked their fields collectively. Therefore, the adoption of a new type of plow was not an individual decision but a communal one. Finally, the heavy-wheeled plow required a substantial investment in animal power because, as its name suggests, it was heavy; sometimes peasants needed as many as eight oxen to pull the plows. Oxen were also expensive and often stubborn.

As knowledge of the selective breeding of animals improved, Europeans employed draft horses to pull the plows. Two draft horses could pull the plow much more rapidly than four or eight oxen. The draft horses were also more maneuverable and cooperative. With a heavy-wheeled plow hitched up to two draft horses, a peasant could work more land with greater effect.

Another significant factor in the improvement of agricultural output was the adoption of crop rotation. During the High Middle Ages some manors adopted the three-field system, which addressed the problem of nitrogen depletion caused by growing grain successively in one field. Europeans had known about this problem for centuries and had often implemented the two-field system during the Early Middle Ages. This system featured grain production in one field, while another field sat fallow, possibly with some livestock grazing. However, the three-field system included a third field with a nitrogen-fixing crop, such as beans, peas or clover, planted in the Spring. These crops absorbed nitrogen from the atmosphere and secreted it into the soil. Once this Spring crop was harvested, usually in the late Summer, the livestock could graze that field and their manure further enriched the soil. In a three-field system, the peasants then rotated the crops at the end of the manorial year, which occurred near Michaelmas at the end of September.

Because only a third, instead of half of the land, remained fallow compared to the two-field system, more land was productive at any given time. The three-field system also increased the nitrogen content of the soil so that the yields of the grain harvest improved. Whereas the yields in a two-field system could be as low as 2 to 1 or 4 to 1 pieces of grain per seed planted, yields in a three-field system were often two to five times higher than in the two-field system. In addition, the three-field system could support more livestock because the three-field system often provided more nutritious feed for animals. Consequently, Europeans ate more meat with the adoption of the three-field system. The meat provided more iron in the diet, an added benefit for pregnant women, who suffered severe blood loss and sometimes mortality during childbirth. For the first time in European history, women as a group started to outlive men, partly as a result of more iron in their diet.

Additionally, the conversion of grain into usable flour became more efficient as windmills and watermills populated much of the European countryside, especially north of the Alps. The difference in speed between hand-grinding grain and using a mill was dramatic. It could take most of a day to grind enough flour to bake bread for a family, but a mill could grind fifty pounds of grain in less than a half hour. Although peasants resented having to pay for access to mills, typically controlled by the warrior aristocracy or the Church, the increase in productivity constituted a big attraction despite the exploitative nature of the mill fees.

Improvements in agricultural techniques, along with longer life expectancy for women, stimulated significant population growth in Europe during the High Middle Ages. Between 1000 and 1300 Europe’s population more than tripled from approximately 30 million to approximately 100 million people. Unfortunately, we do not have exact numbers as governments did not perform censuses. However, manors often kept track of births and deaths, and births outnumbered deaths over the three-hundred year period.

Gradually, as agricultural productivity improved and as the European population grew, markets arose. Many manors shifted away from a subsistence economy that featured the production of many crops, even those that did not thrive in certain climates and soils. Peasants chose to plant those crops that grew most vivaciously on their land, relying on the burgeoning markets to supply them with goods that were not as likely to succeed on their plots. Thus, specialization increased as a small but growing number of people relied on markets rather than trying to subsist only on what they could produce for themselves. In short, markets enabled specialization which further enhanced productivity and the diversity of goods that were available. Market towns and cities grew, although they remained small by modern standards.

Europe’s largest cities formed in Italy during the High Middle Ages. Naples boasted at least 80,000 people by 1300. Further north, Rome remained puny with only 10,000 inhabitants, compared to over a million in its imperial glory in the first century CE. By contrast, Florence and Venice were lively merchant republics with well over 50,000 people at the end of the High Middle Ages. The growth and independence of northern Italian mercantile city-states accelerated during the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Their development often involved violent uprisings against the traditional warrior aristocracy by merchants and laborers of lesser means and lower status, who established representative governments dominated by men of commerce instead of men at arms. In the Late Middle Ages the republics of the northern Italian city-states became the breeding ground for the pronounced production of literary, artistic, architectural, and engineering achievements that historians refer to as the Italian Renaissance.

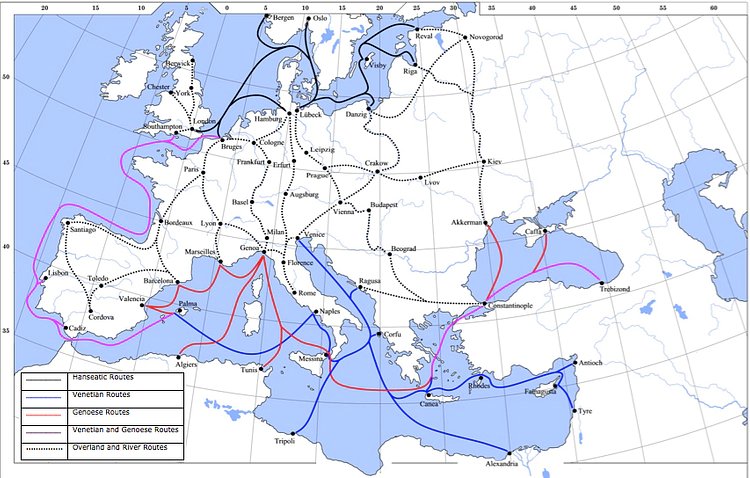

Because the Mediterranean had been an incubator of vibrant trade routes for millennia, the Italian city-states during the High Middle Ages had a distinct advantage. They functioned as a point of entry for the importation of luxury goods from the eastern Mediterranean, which had been more urban, cosmopolitan, and sophisticated than most of Europe for millennia. The importation of spices, porcelain, silk, and other luxury goods was particularly lucrative, and Genoa, Venice, and Florence became prominent centers of international trade by the 1200s.

North of the Alps, the situation differed substantially. There were fewer cities, and they tended to be much smaller with less political independence. Consequently, northern European merchants tended to be less powerful in relationship to the warrior aristocracy, who often demanded high taxes and tolls for commercial activities. Nevertheless, merchants communities formed. One such community arose in the Champagne region of France, where a series of towns took turns hosting trade fairs throughout the year between 1150 and 1300. These fairs improved contacts between merchants in northern and southern Europe particularly in the cloth trade.

Also beginning in the 1100s, merchants in Lübeck, northern Germany (the Holy Roman Empire), increasingly organized into guilds. This form of social organization strengthened their ability to negotiate some level of independence from noble taxation, and by the 1200s they established the rudiments of, what became known as, the Hanseatic League or Hansa. They established a flotilla system that protected ships at sea from pirates, and they armed caravans on the land to protect against nobles who sought to exact fees from Hansa members. However, as the Lübeck merchants gradually allied with guilds of merchants from other cities across the Baltic and North Seas, their ability to resist the depredations of the warrior aristocracy and pirates improved. The Hansa developed a powerful presence from London to the Slavic republic of Novgorod in modern-day Russia.

Other types of guilds also arose across Europe during the 1100s. Aside from the merchant guilds, which resembled a more localized version of the Hansa, craft guilds arose in various nascent industries. Some guilds, such as goldsmiths and armourers, specialized in producing products for the nobility. Others catered to a broader clientele. For example, cloth production often involved many different specialized processes including carding, weaving, dying, and fulling. The guilds ensured some level of standardization and quality in each of these manufacturing processes. By the 1200s they had become ubiquitous in Europe, and they gradually ensconced themselves in the administration of most cities. They enforced regulations related to the behavior of guild members, who essentially controlled economic activity in urban centers. In addition to these economic functions, guilds also provided a sense of community and belonging for adult Christian males while excluding women, Jews, and foreigners.

The extension of lands under plow, the improvements in agricultural productivity, and the establishment of robust trade and production networks contributed to the growth of the economy of Europe during the High Middle Ages. This growth did not bring prosperity to most Europeans, however. The exactions wrought by landlords, the tithes collected by the Church, and the taxes levied by the secular rulers enriched those in positions of power. The exploitation both of natural resources and of workers gained momentum for most of the period. This exploitation enabled Europe to accrue the characteristics of an advanced civilization with beautiful cathedrals, fortified castles, and highly literate poets and administrators. Those in power were successful in creating the impression that they deserved to profit from the labor of their subjects and believers. They then invested their profits in acts of patronage to enhance their status and brand, as we will explore more fully when we address the Italian Renaissance in the Late Middle Ages.

The Rise of the Papacy

Although the Bishop of Rome had been one of the original five patriarchs of Christendom, the office was much more limited prior to 1000 than afterwards. Occasionally popes, such as Gregory the Great (r. 590-604), who sent missionaries to convert the early English, and Leo III (r. 795-816), who crowned Charlemagne in 800, exerted bursts of papal authority and success. However, the position of the Bishop of Rome was so contested by ruling families of the central Italian nobility that the extent of papal influence outside of the Italian peninsula was extremely limited before 1000 as powerful nobles appointed their own popes and declared others to be antipopes. It was hard to claim wide ranging powers or divine approval when rival claimants to the office also boasted those same rights and powers. Further exacerbating the impact of the internecine conflicts between Italian ruling families, the Christian morality of the individuals holding the office was often suspect at best. The result was that the papacy prior to 1000 had a fraction of the power that it gained in the High Middle Ages.

The most influential catalyst for the reform and strengthening of the papacy was the monastic reform movement. It started in Lorraine and in Burgundy during the 900s. Over the course of the next two centuries it became one of the most disruptive movements in European history because it threatened to transfer enormous wealth and power away from aristocratic families and into the hand of the Church. For the most part, it was successful in this endeavor until the 1500s, when many secular rulers confiscated monastic lands during the Protestant Reformation. The essence of the movement was two-fold.

First, the warrior aristocracy (nobles) had long established monasteries for the salvation of their souls. Monks in these family-controlled monasteries plied the Lord for mercy in order to atone for the atrocities committed by the founders of their monasteries. The nobles treated these monasteries as familial property. Members of noble families governed the monasteries and nunneries as abbots and abbesses. The running of monasteries and nunneries provided younger sons and daughters of nobles with career paths that did not interfere with the family patrimony. Instead of inheriting the family properties in the secular realm, the ecclesiastical aristocrats often busied themselves with the affairs of the Church and of local monasteries that the family controlled.

Second, in such an environment the dedication of the monks and nuns in these monasteries was suspect. They rarely adhered to the tenants of Benedictine rule, including moderation, hard work, obedience, celibacy, and humility. Instead, they drank, fornicated, and hired peasants to do their labor. Occasionally, the Church leaders intervened and attempted to establish order. However, without oversight and guidance from dedicated brethren, the monasteries suffered from bouts of moral decay and self indulgence. Many monasteries were a blemish on the reputation of the Church as a source of moral authority.

Determined to reverse these lapses in the rule of St. Benedict, two different movements arose, one in Lorraine (the Holy Roman Empire) under Otto I (r. 962-973) and one at Cluny in Burgundy, under the control of Duke William the Pious of Aquitaine (r. 895-918). The purpose of these movements was similar. If the Church was to improve its influence among the powerful nobles, it had to improve its prestige. Monks in these monasteries could no longer disregard their vows. The proposed way to enforce such a program was to wrest the estates of the monasteries away from the noble families, who considered monastic lands to be part of their family patrimony. While the movement at Lorraine demonstrated enormous scholarly dedication and devotion, Cluny became the dominant force in the monastic reform movement because it established a hierarchical structure that supervised the activities of monks in hundreds of monasteries by 1100.

Cluny’s mission to exert control over hundreds of monasteries and their enormous landholdings divided the European nobility. Some nobles who believed in the aspirations and goals of the reformers supported it wholeheartedly. Others who were threatened by the Church’s attempt to wrest control of lands held by their family for generations resisted reform vigorously and sometimes violently. Because land was the source of most wealth, the reformers constituted a threat to the economic resources and privileges of many nobles. Nevertheless, the movement was ultimately successful partly because monarchs often supported it. It weakened the power of many of their nobles, but it also gradually increased the wealth, prestige, and power of the Latin Church and its leadership in Rome.

Reassured by the growing wealth and prestige of the Church, the reformist leaders of the Church cultivated powerful allies. Among them was none other than the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry III (r. 1046-1056). Henry exercised enormous control over members of the clergy in his territories, the very practice that monastic reform opposed. However, Henry also recognized the advantages that a reformed Church could impart to emperors, such as himself, who typically received their coronation from the Bishop of Rome. If the popes became more prestigious, the emperor would too, because the pope recognized his authority. Similar to many monarchs after him, Henry sought to control the increasingly powerful Church leaders as a strategy to strengthen his claims to power. However, during the High Middle Ages, secular leaders such as the Holy Roman Emperor and the King of England sometimes underestimated the growing power of the Church and its leaders. And, as we will see in the following sections of this chapter, this competition for power between Church and secular leaders had fundamental effects on European political development.

When Henry III died in 1056, he left behind a six-year-old son, Henry IV (1050-1105). During the young king’s minority, the leaders of the reform faction in the Church strengthened their control of the papacy and its independence from the Holy Roman Emperor. They cultivated powerful allies to the south of Rome in 1059 when they concluded the Treaty of Melfi, which recognized the Normans’ claims to parts of southern Italy and Sicily. The result was the removal of Byzantine and Muslim rulers in those regions. Although relations with the Norman rulers in southern Italy were often strained, the papacy was becoming increasingly aware of the power of religious conviction to inspire men to go to war.

By the 1070s, the popes engaged in open conflict with the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV. The conflict arose over a number of issues, including the right to appoint bishops. This conflict, sometimes referred to as the Investiture Controversy or Investiture Contest also addressed the power of the Holy Roman Emperor in Italy and the pope in Germany. It was part of a larger competition for power that spread across much of Europe for the next three-hundred years as popes and secular rulers sought to exert their control, not only over the appointment of Church officials, but also over the rights to collect taxes and to administer justice. This competition for power grew out of the rising prestige of the papacy, which allowed popes to influence events well beyond the Italian peninsula, and it only intensified as a result of the crusading movement, which began near the end of the eleventh century.

The First Crusade, 1095-1099

Emboldened by the rising power and prestige of his office, Pope Urban II (r. 1088-1099) traveled across the Alps from Rome to Clermont, which lay in the heart of modern-day France. Francia at this time (November 1095) was suffering from frequent bouts of chaos and violence. Many knights wantonly disregarded any allegiance they may have had to an overlord. They built wooden castles and considered land conferred to their ancestors by Frankish kings as their own. Despite the attempts of ecclesiastical leaders to reform the Church and society, political authority had few moral obligations. Might made right. Violence disrupted commercial and cultural activities.

For over a century, since the late 900s, Church leaders had attempted to persuade members of the knightly class, who raided the countryside from their rudimentary castles, to recognize certain constraints on their behavior. As described in the previous chapter, the Peace of God and the Truce of God arose as social movements, inspired by local clergy, to persuade knights to restrict their violence against non-combatants and to limit violence to certain time periods. Neither movement was particularly successful. Urban II understood that violence was endemic to much of Francia, and he addressed the topic in 1095 at Clermont, where he convened a council composed mostly of Church leaders. There he noted the prevalence of violence and the need to correct local clergy who had made their services available to the corrupt local nobility. He cautioned the clergy in attendance to care for their local congregations as a shepherd would for a flock. He reminded them of the horrors of Hell for failure to take their clerical responsibilities seriously.

Urban II then asked his listeners to spread the news that the lands of the Romans, meaning the Byzantine Empire, had suffered invasions from people he deemed abominable. He called all Christians who recognized his authority to save their brethren in the east. Although relations between the papacy and the Byzantines were not particularly friendly in the late 1000s, he implored those in attendance to liberate eastern lands, including Byzantium and the Holy Land, from the control of the Seljuk Turks. Several sources recorded the speech of the pope, and his precise motives for proclaiming the crusade have attracted the attention of numerous historians.

Whatever the pope’s motives, the crusade was a qualified success for the office of the papacy. Clergy left the Council of Clermont in November 1095 and encouraged their flocks, their parishioners, and their neighbors to travel to the Holy Land to liberate Jerusalem from this alleged threat. Although some preachers may have presented their quest to perpetuate violence against non-Christians in terms of protecting pilgrimages to the Holy Land, the pope’s speech was not so limited in its goals, and various preachers interpreted the pope’s exhortation differently. The liberation of the the lands under Muslim rule constituted his primary talking point. However, given the widespread dereliction of the Frankish knights who had failed to adhere to oaths to abide by the Peace and Truce of God, the pontiff understood the need for those warriors to save their souls. He promised the cleansing of sins for those who undertook the journey to the Holy Land, including those who died before they arrived.

Although the papacy had framed warfare in religious terms in the past, the reaction to the Clermont speech and the subsequent preaching of the First Crusade was unprecedented. Europeans responded in the tens of thousands; maybe as many as 50,000 crusaders heeded the message. If so, it was the largest army in European history since the Romans and their allies met Attila the Hun and his allies at the Battle of Chalons in 451 CE. Commoners and nobles left their families in Francia, the German Empire, southern Italy, England, and Flanders to join a growing pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Before trekking across central and eastern Europe, a large number of them attacked Jewish communities along the Rhineland, most notably at Cologne and Mainz. This anti-semitic response to the call for crusade highlighted the crusading rhetoric’s prmotion of violence, intolerance, and divisiveness. It was not just the liberation of the Holy Land that the crusaders sought. Encouraged by the rhetoric against non-Christians, the crusaders attacked Jewish communities who had inhabited the Rhineland and contributed to the growing culture and commerce of the area since the time of Charlemagne.

As the crusaders marched eastward through the recently-converted Christian Kingdom of Hungary they sparked fear among Christians and Jews. Led by a charismatic preacher, Peter the Hermit, and some nobles, most notably Godfrey of Bouillon, who later became the first ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, they caused panic and mayhem wherever they traveled. The Christian Hungarians responded and massacred a few large bands of the disorganized crusaders. By the time they reached Constantinople in late 1096, the crusaders constituted a threat to order and safety in the city. The Byzantine emperor ferried them across the Bosphorus to Anatolia, where they met a swift and decisive defeat at the hands of the Seljuk Turks. A few thousand of the survivors, including Peter and Godfrey, retreated in safety to Constantinope to await the arrival of more organized, professional warriors, mostly from southern Italy, France, and Flanders. So ended the first wave of the First Crusade, sometimes referred to as the People’s Crusade.

It is safe to say that the People’s Crusade was not what Urban II had in mind in late 1095 when he proclaimed the crusade at Clermont, where he had met with Adhemar, Bishop of Le Puy, to plan the journey to Jerusalem. The first wave of crusaders was disorganized and ineffective. By contrast, after the pope appointed the bishop as his legate or representative, nobles and their retinues gathered under the leadership of Raymond, Count of Toulouse, one of the wealthiest and most powerful nobles in Adhemar’s diocese. Other bands coalesced, principally among the Normans both in Sicily and in France and also under the leadership of the Count of Flanders.

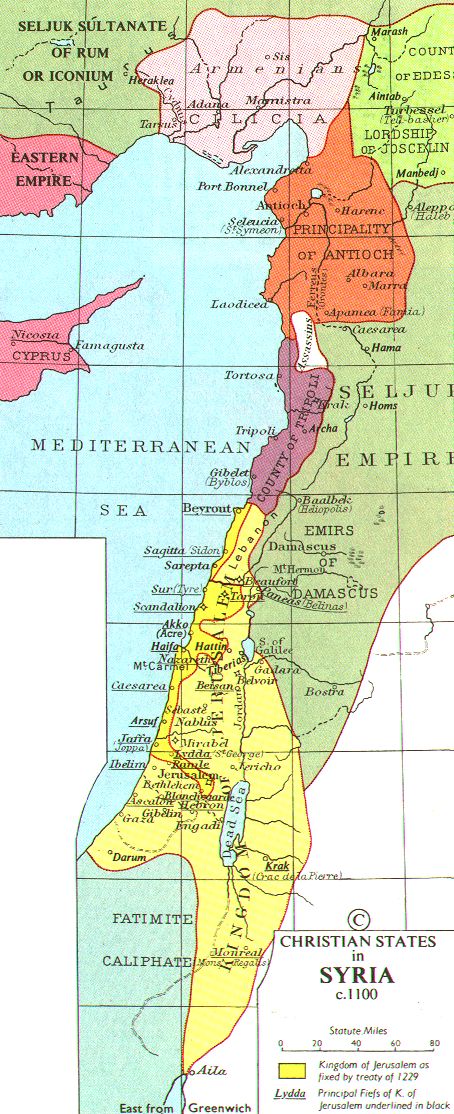

In short, this second wave of the First Crusade, the Princes’ Crusade, consisted mostly of the type of warriors who had proven so disruptive to political stability in Francia for more than a century. In late 1096 and early 1097 they traveled in separate clusters to Constantinople, where they swore to the Byzantine emperor oaths of loyalty, oaths that they would later forswear. They often quarreled among themselves, but they maintained enough unity to capture Edessa and Antioch in 1098, and ultimately Jerusalem in 1099. By 1102, they established a contiguous strip of Latin Christian territories that stretched from the Sinai Peninsula to Anatolia. The leaders and their retinues were hardened warriors who had caught many of the Muslim inhabitants of the Holy Land completely unprepared for this type of religious-inspired violence.

Pope Urban II died two weeks after the capture of Jerusalem in July of 1099. He never heard the news. However, the office of the papacy benefitted mightily from the success of these bloody victories. Over the coming century, the bishops of Rome became some of the most powerful leaders in Europe. The First Crusade had demonstrated the popes’ ability to rally Europeans to their banner, to fight wars, to murder innocents, and to inspire their followers to undertake enormous personal and familial risks for the defense and extension of Latin Christendom. The First Crusade also demonstrated the powerful response to the pope’s claim to remit sins. The promise of facilitating entry to a blissful, eternal afterlife had enormous attraction. In the coming centuries the papacy continued to dangle this carrot in front of Europeans when popes wanted to raise money to wage wars against political rivals and heretics.

Religious Enthusiasm

In addition to altering the balance of power between the papacy and secular rulers across Europe, the First Crusade also reinforced the collective identity of the Latin Church’s followers. A shared sense of Christian values, history, and culture manifested in a variety of ways: the establishment of social organizations, the patronage of great literary and artistic works, the building of architecture, the development of theories related to religious doctrine, the persecution of non-Christians, and the waging of religious wars. Oftentimes, the religious enthusiasm sparked by the success of the First Crusade and the rising prestige of the papacy encouraged the defining creative and intellectual works of the High Middle Ages. On other occasions, the deep sense of devotion caused immense pain and suffering both for Christians and their adversaries, both real and imagined.

Crusading inspired Europeans to explore new ways to organize themselves into Christian communities. Of course, they had been creating such communities since Jesus had gathered his apostles. However, as the European economy expanded and the population developed more socioeconomic and cultural diversity, the types of Christian communities diversified to meet the needs of a more heterogeneous Europe. In response, the papacy sought to control the proliferating modes of Christian association, lest they stray into heretical beliefs and practices. Typically, these heresies arose in areas where trade enabled the dissemination of ideas. Cities tended to house more diverse, literate, and cosmopolitan populations, and the emerging religious orders and movements of the High Middle Ages often addressed the various devotional needs of an increasingly urban and heterogeneous society.

The Mediterranean ports were one of the principal areas where these trends were in evidence. The Templars and Hospitallers were military-religious orders that formed in the wake of the conquest of Jerusalem. Their initial purposes were to protect pilgrims to the Holy Land and to protect the Holy Land itself. By the end of the Third Crusade (1193), the Teutonic Knights formed as an order in the port city of Acre in the Levant, but like the Templars and Hospitallers, their sphere of operations shifted away from the Holy Land and toward Europe after the Crusader States collapsed during the 1200s. The Templars became international bankers. Their rivals, the Hospitallers, settled for political control of islands in the Mediterranean and eventually the Carribean, and the Teutonic Knights ruled over vast stretches of northern and eastern Europe near modern-day Poland. All three of these military religious orders melded Christian practices, such as asceticism and celibacy, with knighthood in what St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) deemed a new form of chivalry.

In addition to these military orders, several ascetic Christian sects of monks formed. Asceticism had always been one of the defining features of Christianity, and it became a prominent element of both orthodox and heretical Christian movements in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. One of the most prominent ascetic Christian movements of the early 1100s became known as the Cistercian order or the White Monks to differentiate them from the more traditional Benedictine order or Black Monks (discussed in previous chapter). The White Monks practiced a more austere form of the Benedictine rule established around 600 by Gregory the Great. They believed that the Black Monks had become lax in their observance of the rule. The monastic reform movement of the tenth and eleventh centuries (described above) had intended to mitigate some of the lapses in the observance of the Benedictine rule. However, the reforms gradually faded in many monasteries, including the mother house at Cluny. During the First Crusade in 1098 a group of monks, led by Robert of Molesme, left the Cluny abbey to found a new monastery dedicated to a more strict observance of the rule of St. Benedict.

The Cistercians initially settled in some swampland south of Dijon in Burgundy. They drained the swamp, cleared trees, and turned wasteland into productive agriculture holdings. This dedication to undertake hard work in a collective effort combined with their willingness to experiment with crop rotation and other innovative forms of agriculture sustained the order’s economic footing as it gradually expanded across Europe during the 1100s. During the order’s heyday in the first half of the twelfth century the Cistericans attracted the most charismatic holy man in Europe: Bernard of Clairvaux. Bernard became a powerful presence in the growth of the order and his name became legendary across Europe. He prayed routinely to the Virgin Mary, a somewhat innovative form of devotion in Latin Christianity during the 1100s. In addition to encouraging converts to the Knights Templar, Bernard was an austere ascetic and a mystic. These approaches to Christian devotion put him into conflict with Christians who sought to uncover the divine through the study of logic.

Shortly after the fall of the crusader state of Edessa at the end of 1144, Bernard began advocating for the Second Crusade (1047-1150). In Burgundy Pope Eugene III (r.1145-1153) commissioned Bernard to preach the crusade in 1145. The pope understood Bernard’s capacity to influence powerful people, such as the monarchs of France (Louis VII and his queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine) and the German imperial family (Conrad III and his nephew, Frederick Barbarossa). The leadership of the Second Crusade differed markedly from the First Crusade, which had no monarchs. The inclusion of monarchs should have been a boon to the crusading effort; however, the lack of coordination and cooperation between these rulers undermined the crusade’s success. They ultimately failed to reclaim Edessa and Bernard, at one time the crusade’s most vocal proponent, ultimately characterized the Second Crusade as a humiliating defeat.

Edessa had been one of the first crusader states; however, its stability had always been dependent upon outside support. Its conquest in 1144 under the leadership of Imad al-Din Zengi (r.1127-1146), commonly referred to as Zengi, signaled a rising unity among the disparate Muslim states in opposition to Christian control of the Levant. The failure of the Latin Christian monarchs to retake Edessa encouraged the formation of a face-saving plan: the conquest of Damascus. The plan was never particularly well thought out. Damascus had opposed Zengi and his army. The political situation in the Levant was more complicated than the crusaders realized. Their siege of Damascus in 1148 was such a dismal failure that the crusade fell apart shortly afterwards. The crusaders returned to Europe.

The Second Crusade’s only military success from a European perspective did not take place in the Levant. Instead, it occurred on the Atlantic coast of the Iberian peninsula during the summer of 1147 when northern European ships headed for the Holy Land sought refuge from rough seas. Landing in Porto, they came into contact with the first king of Portugal, Alfonso I (r. 1139-1185), who enlisted the military services of the crusaders by offering to let them plunder and despoil the city of Lisbon if they wrested it from the Muslims, who had held it for over 400 years. Despite some infighting between the English and Flemish crusaders, they managed to force Lisbon to surrender in less than four months as the large population grew short of supplies.

These warrior Christians started their voyage as part of the Second Crusade but ended up as part of the reconquista, which had begun during the late 700s and would continue until 1492. Although the reconquest of the Iberian peninsula had progressed slowly during the 800s and 900s, by the eleventh century Christian soldiers were rallying against al-Andulus, a collection of Muslim states that controlled the southern half of the Iberian Peninsula. Unsurprisingly, Europeans found it much easier to conquer and hold land closer to their heartland, what became known as Continental Europe rather than in faraway territories, such as the Near East.

Despite or perhaps because of these religious conflicts, trade and intellectual exchanges between Europeans and Muslims increased during the twelfth century. The Holy Land had long been a portal between Mediterranean commerce and trade routes, such as the Silk Road, from India and the Far East. As such, the control of this area by Christians enhanced the profits of Italian merchants, who already had significant trade infrastructure in place before the crusades. The influx of capital generated as a result of the crusades enriched Italian merchants who increasingly sent their children to study in universities, which originally appeared in the Italian peninsula during the eleventh century and spread to much of Europe by the thirteenth century. Although modern universities in Europe are mostly secular, during the High Middle Ages they constituted religious communities, focused on the study of ancient authoritative texts in both the Christian and Greco-Roman traditions.

The success of the reconquista contributed significantly to the growth and development of these emerging educational institutions. The Iberian peninsula had long been a center of learning admired by Christian monks. Around 970 Gerbert of Aurillac, later Pope Sylvester II (r. 999-1003), had studied Arabic texts and especially mathematics in Catalonia. He used Arabic numerals and re-introduced the abacus to Europe. His admiration for the learning and resources of the Kingdom of Cordoba inspired some to claim that he was in league with the Devil, while others recognized his intellectual leadership.

One hundred and fifty years later, by the end of the Second Crusade, the previously Muslim city of Toledo became the epicenter of an unprecedented translation effort. Although some translations proceeded from Arabic to Castilian and then into Latin (the primary language of intellectual discourse in European universities), many followed a more direct route from Arabic to Latin. The most productive of these translators was probably Gerard of Cremona (1114-1187), who translated over 80 books from Arabic into Latin. Most of the books were of a scientific and mathematical nature. In Toledo he rendered into Latin Ptolemy’s work on astronomy, the Almagest, which had originally been composed in Greek. This work was virtually unknown in western Europe at the time, but it was well known in Constantinople. This lack of cooperation between the Byzantines and the Latin Christians highlighted how poor relations were between Greek Orthodox Christians in Byzantium and Latin Christians. Gerard also wrote original works on mathematics and algebra, and his writings eventually persuaded Latin Christians to adopt Arabic numerals.

The harvesting of knowledge from the Toledo libraries was not limited to astronomy and math. Benedictine monks, traveling from Cluny and Italy, worked with local Mozarabs (Christians who spoke Arabic), Jews, and Muslims to render ancient and Islamic sources into the language of western European intellectuals: Latin. They translated works covering Euclidean geometry, optics, medicine, ethics, physics, and logic. The latter was especially relevant to the burgeoning form of intellectual activity in the Christian universities: scholasticism, a method of harmonizing apparent contradictions through logic. It often addressed the verity of Christian belief through the application of logic. When addressing the complicated topic of the Divine, both Muslims and Jews had developed similar approaches, such as the Kalām, the study of Islamic doctrine.

Some teachers in the scholastic tradition became intellectual celebrities. The most controversial of these teachers in the twelfth century was Peter Abelard (1079–1142), a Parisien philosopher, poet, composer, and theologian. He explored both the pros and cons of various important questions that had been considered by the Church fathers. Abelard specialized in the application of reason to faith; he argued that ultimate truth could and should sustain reasoned investigation of its precepts. By emphasizing the quest for truth even if it contradicted Church dogma, he fell afoul of the Church authorities, and especially of Bernard of Clairvaux, a powerful Church leader. Abelard’s point was that educated Christians should challenge their own beliefs and try to understand them. He advocated for reliance on the Bible as the ultimate source of truth in order to expand Christian knowledge throughout society. Martin Luther would argue a similar point approximately 400 years later. Perhaps unsurprisingly, both men fell afoul of Church authorities.

Medieval universities differed substantially from the modern institutions. Typically, they resembled craft guilds, with organizations of apprentices (students) and masters (teachers) negotiating over the cost of classes and preventing unauthorized lecturers from stealing students. Students often paid teachers directly, and there were no grades. Teachers were generally members of the clergy, “professing” religion, hence the term “professor.” A guild of students founded the first university, a law school at Bologna in northern Italy in 1088. However, by the 1200s the Sorbonne in Paris became the most prestigious university in Europe, partly because of its emphasis on theology, which many considered the highest form of intellectual activity with its emphasis on studying the divine. The University of Paris had emerged from the cathedral school of Notre Dame, where Abelard had taught in the 1100s.

Despite these differences from modern practices, medieval universities created a number of traditions that live on to the present in higher education. They drew up a curriculum, established graduation requirements and exams, and conferred degrees. The robes and distinctive hats of graduation ceremonies are directly descended from the medieval models. The core disciplines, which date back to Roman times, were divided between the liberal arts of grammar, rhetoric, and logic (called the trivium) and what might now be described as a more “technical” set of disciplines: arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music (the quadrivium) – this division was the earliest version of a curriculum of “arts and sciences.” Finally, the four kinds of doctorates, the PhD (doctor of philosophy), the JD (doctor of jurisprudence, that is to say of law), the ThD (doctor of theology, a priest), and the MD (doctor of medicine), are all derived from medieval degrees.

The overwhelming majority of students and professors were male, since the assumption was that the whole purpose of studies was to create better church officials. However, in the thirteenth century Bettisia Gozzadini (1209–1261) became the first woman not only to receive a degree in a European university, but one of the first to teach at one as well. Because of the highly patriarchal nature of medieval society, many of the great female thinkers of the period were either wealthy enough to hire a tutor or were nuns who had access to the often excellent education of the convents. One outstanding example of a medieval woman who was known in her own lifetime as a towering intellectual figure was Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), abbess of a German convent. While not formally educated in the scholastic tradition, Hildegard was nevertheless the author of several works of theological interpretation and medicine. She was a musician and composer as well, writing music and musical plays performed by both nuns and laypeople. She carried on a voluminous correspondence with other learned people during her lifetime and was eventually sainted by the Church. Hildegard was exceptional in her range of intellectual production. Medieval women faced enormous obstacles to their intellectual journeys. Nevertheless, many other religious women, including Peter Abelard’s beloved Héloïse d’Argenteuil, also contributed significantly to medieval learning and scholarship.

The relative dearth of women’s contributions to the intellectual legacy if medieval Europe derived from the oppressively patriarchal structure of the society. If a women was not in holy orders (i.e. a nun), then she was generally expected to marry and raise children. Furthermore, in aristocratic circles, where women might have had the time and resources necessary for intellectual pursuits, families pressured their daughters to marry at an early age, often to men who were much older. Among the aristocracy the average age for girls to marry was in the mid-teens, whereas young men did not marry until well into their twenties. However, these averages obscure the great disparities in age that marked some marriages. Writing in the mid to late 1100s (c. 1170s), Marie de France captured the gruesome situation that faced these child brides to much older men in her lays or stories, which often told of unhappy marriages between young women and their older husbands. Marie’s stories, such as the tale of Yonec, recounted the almost sacred union of true love between an unnamed wife, locked in a tower by her older and apparently impotent husband, and a shape-shifting lover who flew into her tower and brought her delight in bed after receiving the Eucharist from a priest. Although the penalties for women who committed adultery were likely very harsh, Marie’s work celebrated these adulterous unions as an escape from the loveless marriages that were apparently common among the aristocracy of Europe during the High Middle Ages. In short, marriage often precluded any opportunity for women to pursue intellectual interests. For that, a life of celibacy as a bride of Christ (i.e. a nun) was almost necessary.

Although the deep intellectual studies were not entirely new to Europe during the 1100s, scholasticism was becoming the most influential form of intellectual discourse in European universities, where it remained prevalent for more than 500 years. Monks and clerics who attended universities applied scholastic, dialectical reasoning to questions related to the existence of God, access to the afterlife, the nature of divine justice, and many other topics related to Christian theology. Although scholasticism eventually garnered a reputation for sterile debates (how many angels could dance on a pinhead?), it provided an avenue to innovation in religious devotion. Scholastics pioneered the doctrines of Purgatory, which addressed the afterlife, and transubstantiation, which claimed miraculous powers for priests. Both doctrines assumed a growing importance after the Church recognized them as canonical in 1215 at the Fourth Lateran Council.

To the medieval mind, a priest’s ability to transform a wheat wafer into the flesh of Jesus and ordinary wine into the blood of Jesus was nothing short of a miracle. This doctrine claimed that the external appearance and taste of the wine and bread remained unchanged; however, the internal substance had, according

to the dogma, transformed. Inspired by this doctrine celebrations arose across much of Europe during the early 1200s , and by the 1260s Corpus Christi Day had become part of the calendar of the Latin Church (as it still is). Celebrated approximately six weeks after Easter, it provided an occasion for bishops to lead a large, orderly and hierarchical procession through the streets of cities. They held the Eucharist up high for all to see in a device called a monstrance, typically protected by a canopy overhead. Such rituals provided occasions for Christian communities to gather and demonstrate their devotion to a medieval doctrine, a powerful fiction that elevated the prestige of the clergy by claiming that they had supernatural powers.

By the Late Middle Ages most large cities of Europe had religious confraternities, guild-like, male social organizations, formed to support a variety of Christian teachings and customs, such as the feast of Corpus Christi. They discussed the theology, planned the event, and ensured that the celebration remained orderly and respectful. In the coming centuries, the Corpus Christi processions provided moments of tension when the doctrine came under increasing scrutiny by those who questioned the priests’ ability to perform such a miracle. Nevertheless, the Corpus Christi celebrations reflected the depth and breadth of Christian devotion in the High and Late Middle Ages. Performed across the Empire, Poland, Hungary, France, England, and the Mediterranean peninsulas, the celebrations expressed the growing devotion to Christian doctrines.

This devotion became an increasingly visible element of the European urban landscapes during the High Middle Ages. Gothic cathedrals rose to new heights, dwarfing the earlier Romanesque churches. Featuring the pointed fifth arch, web vaulting, and relatively thin pillars, they often showcased large stained glass windows full of Christian iconography. On the exterior they relied on flying buttresses to offload some of the weight from the walls in order to accommodate the large windows. They towered above the urban landscape and struck awe into the minds of newcomers to the cities. For locals, they fostered a sense of civic and religious pride.

The intensification of religious devotion during the High Middle Ages assumed many forms from theological disputations to celebrations of Christian saints and doctrines to the formation of religious military orders, such as the Hospitallers, Templars, and Teutonic Knights. Church leaders fanned the flames of devotion, which often had constructive consequences in terms of intellectual, social, and artistic development. However, as the Church became more wealthy and powerful partly as a result of intensified devotion, it attracted the jealousy, fear, and even hostility of some secular leaders. Its legions of well-educated clerics, administrators, and lawyers in addition to its ability to raise the largest armies in Europe put it in direct competition with emperors, kings, and princes who developed a wide spectrum of approaches to dealing with the ecclesiastical colossus. This tension lasted into the Late Middle Ages even as the power of the Church began to wane during the 1300s.

To a certain degree, the Latin Church was a victim of its own success. Religious enthusiasm was so intense that the Church could not control the beliefs and actions of the devout. This tendency emerged clearly during the crusades when fervent Christians attacked Jewish communities during the First and Third Crusades. The pogroms in the Rhineland in 1095 were led by preachers and minor nobles. They villainized Jewish communities who sought shelter but ultimately suffered either at the hands of the crusaders or by committing mass suicide. A similar pogrom occurred in York England in 1190 during the Third Crusade.

Although the Church officially condemned these horrific events, its leaders often encouraged anti-semitism. At the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, Canon 68 stipulated that Jews must wear identifying clothing to prevent carnal relations with Christians. The canon also demanded that they stay indoors during Easter because they failed to show deference to the Eucharist. Church leaders had always been somewhat ambivalent about Jews, with some leaders appreciating Jewish scholarship and expertise and others claiming that they were responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus, even though crucifixion was a peculiarly Roman form of execution. It was not just Church leaders who promoted these stories. By the middle of the 1200s rumors spread that Jews were eating children and desecrating the Eucharist in private rituals. These stories circulated across Europe for centuries. By the thirteenth century secular leaders who had once relied on Jews for their skills in literacy, medicine, and trade, expelled them from their kingdoms. This trend also continued into the Late Middle Ages.

This dark side of religious enthusiasm was not reserved solely for the persecution of Jews. As the variety of Christian forms of devotion expanded during the 1100s and 1200s, the papacy responded by identifying some Christian groups as heretical. The Christian practice of asceticism had inspired some Europeans to embrace a life devoted to apostolic poverty, living poor as Jesus and the Apostles did. Their behavior differed markedly from the luxury that increasingly surrounded the papacy. This contrast in approaches to Christian devotion divided the Latin Church. For example, most mendicant friars, such as the Dominicans, the Carmelites, and most of the Franciscans, remained orthodox by maintaining a strict obedience to the papacy, even though they embraced apostolic poverty. Other ascetic groups, such as the Waldensians and the Cathars, became the victims of persecution, because they threatened the authority of the Church leadership.

The Waldensian movement, begun by Peter Waldo in Lyon, advocated for the vernacular instead of Latin as the language of preaching and the Bible. Waldensians questioned the emerging Church doctrines of transubstantiation and purgatory. They rejected the Church’s claims on the sacred powers of holy water and relics. In general, they doubted the ability of clergy to perform miracles. The movement spread to the Holy Roman Empire and Italy by the 1200s. Hauled before the medieval inquisition, Waldo recanted and went underground; despite his disappearance from the historical records, the movement continued to spread. The Waldensian sect of Christianity later merged with Calvinist movement during the sixteenth century and survived into the modern period. Some emigrated from Europe to the US.

By contrast, the Cathars were more openly defiant. Their leaders called themselves “perfecti” and eschewed all physical contact with anything that copulated. They formed a rival Church hierarchy in southern France. In 1209, Pope Innocent III (r. 1198-1216) proclaimed a crusade against them that lasted 20 years. Although the Cathar leaders and their followers considered themselves devout Christians, they questioned the holiness and authority of the Bishop of Rome. They attracted members of the southern French nobility, including the Count of Toulouse and crusader heroes to their side, but ultimately they succumbed to the combined forces of the papacy and the King of France, Louis VIII (r. 1223-1226).

The line between heretic and orthodox Christian was not always clear. Originating in the Low Countries and spreading into France and the Empire, beguines were lay women who embraced celibacy and apostolic poverty. Unlike nuns, they could leave their religious life and enter into marriage if they chose. They did not live under the guidance of a religious rule and did not have designated spiritual oversight from a priest. This level of freedom for communities of religious women was very rare. They never received a license from the pope, and they gradually attracted many critics. By the Late Middle Ages they faced open hostility from Church authorities. In 1310 the Inquisition sentenced Margueritte Puerette, a beguine mystic, to death by burning. Although beguine communities continued to attract adherents well into the 1500s, their status vis-à-vis Church authorities remained more than uncomfortable.

Another group that skirted the lines between heresy and orthodoxy was the Spiritual Franciscans. They emerged as devout adherents of the Franciscan order, which received papal recognition and blessing in 1210. Francis himself became a religious celebrity. He traveled on the Fifth Crusade and attempted to convert the Sultan of Egypt without success. The Church recognized him as a saint less than two years after he died, an unusually short period of time for such an act. In the coming decades Franciscans attracted the admiration of Christians across Europe for their devotion to apostolic poverty. Many were also excellent preachers. Ironically, the order became wealthy from pious bequests, and its members gradually splintered into two groups: the Coventuals accepted the growing wealth of the order and the wealth of the Church, while the Spirituals remained ardent proponents of apostolic poverty. Some Spirituals embraced messianic prophecies and identified the pope as the antichrist. Unsurprisingly, they gradually came into conflict with the papacy, and in the 1320s and 1330s Pope John XXII declared them heretics and ordered many of them imprisoned and burned. A similar group of ardent Franciscans emerged in the 1400s. Known as the Observants, they refrained from attacking the pope and continue to exist.

During the High Middle Ages the breadth and intensity of religious devotion was on full display. Christianity proved to be malleable as an increasingly diverse population adapted the religion to its needs. The crusades, the reconquista, international trade, the formation of guilds and cities, and the spread of literacy broadened the experiential and intellectual horizons of broad cross sections of society. As these different groups sought to reconcile their faith with their experiences, Latin Christianity resembled a collection of religions 300 years before the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s. Limiting the range of religious expression, the papacy sought to maintain a semblance of coherence and, more importantly, the recognition of its authority over religious expression. It did not always succeed.

One of the clearest episodes of the papacy’s lack of control over its believers occurred during the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204). Initially intended to be an expedition to attack Cairo, the seat of power over the Holy Land, the crusade changed course before it left port. As most of the crusaders descended on Venice as the point of embarkation for the crusade, the Venetians demanded a contractually-agreed-upon compensation for transporting the crusaders across the Mediterranean. When the crusaders were unable to pay the full amount owed, the blind, nonagenarian Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, forged a deal between the Venetians and the crusaders. They invaded Venetian adversaries in the city of Zara, in modern-day Bosnia, where they installed a pro-Venetian government. They then proceeded to attack another Christian city, Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire.

The pope, Innocent III, excommunicated the crusaders twice on the crusade, which never really materialized in Cairo because the crusaders became preoccupied with plundering Zara and especially Constantinople. The pope eventually lifted the excommunications as he realized that the crusade had eliminated one of his main rivals for religious authority, the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Religious enthusiasm constituted a powerful force for shaping European culture. It inspired great works of art, such as the paintings of Giotto (c. 1267-1337), the poetry of Dante (1265-1321), and the monumental architecture of the period: Gothic cathedrals. It was such a powerful cultural force that it intoxicated the leaders of the Church, who claimed to represent God and to perform miracles. However, power in Europe remained highly contested, fragmented, and contingent even by those who claimed to be the successors of Roman imperial rulers, the popes and the emperors. In fact, the competition for power was one of the most powerful forces to shape European political and cultural development during the High Middle Ages. Before we explore that topic, let us turn to one of the most powerful fictions to inspire European rulers to action.

The Quest for Empire

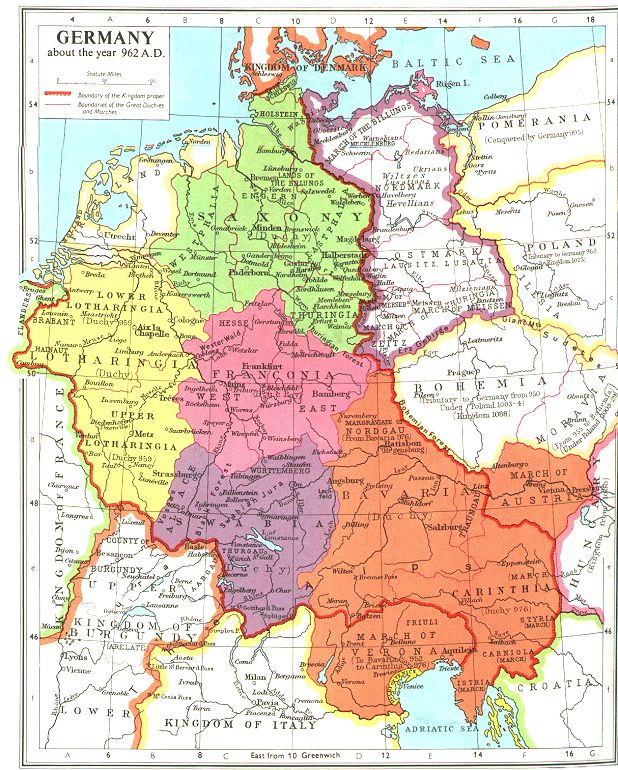

After the collapse of Carolingian power in the 800s, the intention to unite the remnants of the Frankish Empire persisted, especially in East Francia, which became the nucleus of what would later be called the “Holy Roman Empire” during the mid-1200s. Rulers in this region maintained a vision of wielding power in disparate lands, from the northern parts of Germany and Poland on the Baltic Sea to central and even southern Italy and Sicily in the heart of the Mediterranean. Inspired by the quest to reconstitute Roman imperial rule, this vision was mostly at odds with the ability of would-be emperors to exercise such power effectively, and it was typically contingent upon recognition by the pope. Consequently, German kings often felt obliged to extend their power into the Italian peninsula in order to substantiate the impression that they were successors to Roman emperors and also to pressure popes to recognize their authority. This ambitious paradigm for political control repeatedly undermined the German emperors’ control over their native lands north of the Alps; rebellions arose, and loyalties fractured as the strains of the imperial vision took their toll. Consequently, those German rulers who claimed to be emperors frequently traveled with sizable armies to and from the Italian peninsula, where their presence was often, but not always, unwelcome. In order to maintain a semblance of authority in such far-flung regions, the emperors often ceded much of their power to local rulers who feigned their loyalty. Gradually, the Holy Roman Empire became a collection of semi-autonomous states that were nominally under imperial control.

The inability to control the empire effectively was in part due to dynastic instability. Three different dynasties, Ottonians, Salians, and Hohenstaufens, ruled as emperors for most of the period from the mid-900s to the mid-1200s. Because these German rulers were frequently at war, subduing uprisings across their dominions, they often died with child heirs, which hampered the orderly transfer of power. In addition, as the bishops of Rome became more powerful by the mid-1000s due to the reform movement (described above), they often allied themselves with the emperors’ imperial rivals in order to preserve and extend their control over parts of the Italian peninsula from their power base in the Donation of Pepin or what became known as the Papal States.

After the death of the last Carolingian king, Louis the Child (r. 900-911), the German nobility established the procedure of electing its king. This procedure attempted to resolve the problems inherent in dynastic kingship; the death of a king without a legitimate male heir provided opportunities for intrigue and even civil war. Despite the attempt to overcome these problems, the elections did not solve the problem. They provided occasions for bribery and political wrangling and invested the German nobles with significant power. The electors typically consisted of the most influential nobles and churchmen in Germany. They traditionally elected the designated heir of the previous emperor, but when an emperor died without a suitable male heir, complications and violence arose.

There was no Holy Roman Emperor from 924 to 962 when rival claimants vied for the title. In 962 Pope John XII (r. 955-964) crowned Otto the Great (r. 962-973), who demonstrated both military and diplomatic acumen. At the time of his coronation Otto had spent most of his reign wresting control of various regions of Germany from other families, defeating the pagan Magyars of Hungary at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955, and exerting his claims to rule northern Italy after his coronation. His son, Otto II (r. 967-983) proved to be less capable but very ambitious. He attempted to extend imperial control into southern Italy, traditionally under Byzantine and Muslim rule. Ultimately, Otto II failed to achieve his designs and died at the age of 28. His successor, Otto III became king at age 3 and emperor at age 16. During his minority in the 980s and 990s his mother and grandmother acted as capable regents, but Otto III died by age 21 in 1002 and left as his successor his Bavarian cousin, Henry II. Henry spent 12 years gaining control of Germany and parts of modern-day Poland before making his way to Rome for an imperial coronation in 1014.

The Ottonian dynasty demonstrated the precarious position of the German emperors for the next 300 years. They relied on the recognition not only of the German nobility, who elected them the kings of Germany, but also of the popes who crowned them as emperors. Further complicating this challenge, the central Italian nobles had traditionally controlled the papacy, giving them power over the German kings as well. These competing responsibilities required military expeditions across the Alps. Despite the efforts of Otto I to revive learning and to build the sort of durable governmental structure that the English had achieved during the 900s, the territory that the Ottonians claimed to rule was much larger. Consequently, the German kings had to practice the same sort of peripatetic kingship that Charlemagne undertook in the 700s and 800s, constantly travelling throughout their dominions suppressing rebellions.

A big part of this challenge involved control of the papacy. Otto III sought to secure the allegiance of the pope by installing his cousin, Gregory V (r. 996-999), as the first German pope. The Italian nobles, under the leadership of Crescentius II, would have none of it. They elected John XVI as a rival pope, referred to as an “antipope” by those who did not accept the rival. Otto had to return to Rome where he proceeded to cut off the nose, ears, and tongue of the rival pope before blinding and publicly humiliating him. He restored his German relative as pope only to have him die under mysterious circumstances the next year. He then appointed Gerbert of Aurillac, who became the first French pope in 999.

The transition to the next dynasty of German kings (r. 1024-1125), the Salians, was relatively smooth. The German princes elected Conrad II shortly after the last Ottonian emperor, Henry II, died in 1024. The system of electors seemed to be working. The new emperor, Conrad II, took precautions to ensure the smooth transition of power to his son, Henry III, by appointing him as joint ruler of Germany at age 11 in 1028. Although Henry III only lived to be 40, he successfully enhanced the prestige of the papacy by supporting the growing reform movement, which opposed the practice of simony, the purchase of Church offices. The papacy had suffered systemic corruption for centuries as nepotism and bribery had scuttled attempts to reform the office. Additionally, multiple claimants fought for control of the Church and its growing resources (described above). Perhaps the most conspicuous embodiment of these problems arose in the 1030s when Benedict IX (r. 1032-1044, 1045, 1047-1048) succeeded his uncle, John XIX (r. 1024-1032) at the age of 20, after his father bribed the papal electors. He later sold the papacy and then reclaimed it. In all, he held the papacy three times between 1032 and 1048.

The Roman people were weary of such corrupt leadership and welcomed Henry III when he removed three rival popes who claimed the office concurrently in 1046 and installed a reformer, who subsequently crowned him emperor. Although the tenure of popes during this period was short due to the violence and chicanery surrounding the office, the emperor Henry III remained committed to reforming the papacy, even as he practiced simony. Henry III apparently believed that the elevation of the prestige of the popes was essential to the growth and power of the office of the emperor. He invested quite a bit of his reign trying to win Italian support for the German kings as rulers of the Italian peninsula, a quest that German monarchs continued to pursue well into the early modern period.

Following the death of Henry III in 1056, the papal reformers continued their rise to dominance as the young Henry IV and his regents sought to avert the crises that often accompanied the reign of a child king. The regents supported the losing side in a civil war that erupted in Hungary. They relinquished powerful positions within the empire in order to gain support from nobles. Most importantly, the regents watched as their opponents among the Italian nobility gained control of the papacy. The young Henry IV’s response was to appoint his own pope. The presence of an antipope was not new, but it crippled Henry’s prestige as rival factions formed across the empire. When Henry IV assumed direct personal rule at the age of 15 in 1065, he found himself in a very difficult position, with his nobles divided over loyalties to rival popes. Although Henry improved his situation somewhat in Germany, the election of the Church firebrand reformer, Hildebrand (Pope Gregory VII who ruled from 1073-1085) magnified a personal and institutional rivalry between the Holy Roman Emperor and the pope. This crisis persisted well beyond the lives of both Henry IV and Gregory VII.