2 Module Two: Project Administration and Leadership

Module Two: Project Administration and Leadership

Module Learning Objectives

- Identify the 5 phases of project management. (CLO 2)

- Name the key participants and roles of a construction project. (CLO 1, 2)

- Recall the inputs and outputs of the initiation phase. (CLO 2)

- Evaluate the decision-making rationale for a construction project scenario, incorporating risks, assumptions, and tasks. (CLO 1, 2)

- Outline the key components of a business case. (CLO 2)

- Review a past case made for a project/purchase. (CLO 2)

Module Essential Questions

- What are the five phases of project management, and how do they contribute to the overall success of a construction project? (CLO 2)

- Who are the key participants in a construction project, and what roles do they play in ensuring effective project management? (CLO 1, 2)

- What are the inputs and outputs of the initiation phase in project management, and how do they influence project planning and execution? (CLO 2)

- How can the decision-making process in construction project scenarios be effectively evaluated, considering factors such as risks, assumptions, and task management? (CLO 1, 2)

- What are the essential components of a business case, and how do they contribute to informed decision-making and project success? (CLO 2)

- How can past project or purchase cases be reviewed to inform future decision-making processes and improve project outcomes? (CLO 2)

Bridge-In

As we get involved in starting up a new project, we want to ensure we are choosing the right project to have the best impact on making our client’s dreams come true! Within this process, the business problem or opportunity is identified, a solution is defined, a project charter is formed, and a project manager is appointed to build and deliver the solution to the customer or owner. The project team is beginning to form, and key participants are in the early stages of identification. Assumptions are made during this process related to codes, regulations, and policies that will help shape the project trajectory. A key part is then to present a business case to the project sponsor and achieve approval to move forward with the chosen project. These are the key concepts we want to address in this module through the recorded lectures, the readings, and a scenario analysis to help you to think through the concepts discussed.

Lesson 1: The Life Cycle of a Building

The Life Cycle of a Building explores the journey of a construction project from conception to completion. Building on the basics introduced in Module 1: Introduction to Construction Project Management, this lesson delves into the structure and progression of a building’s life cycle, highlighting the distinct phases that a project undergoes. As we progress, we’ll take a closer look at each phase within the project management life cycle, focusing specifically on the nuances and key considerations of managing construction projects.

In this video, we will talk about the project management life cycle. As we learned in the Introduction to Construction Project Management, a project is a temporary endeavor with a distinct start and finish. Every process that takes place with project activities fits within a process group and knowledge area. We’re now going to go into what that life cycle looks like from start to finish. We’ll use all these concepts as we move to the following modules where we’ll dive a bit deeper into each of the project management life cycle phases by focusing on specific concepts of construction project management.

Introduction to the Project Management Life Cycle

The Project Management Life Cycle is crucial for ensuring the successful execution and completion of any project, particularly in the construction industry. It encompasses a series of phases that guide the project from initiation through to closure, providing a structured approach for managing the complexities of construction projects. This cycle is especially relevant when considering the broader life cycle of a building project, emphasizing the need for meticulous planning, execution, and maintenance.

Initiating Phase

The initiating phase is where the project’s vision is formed. It begins with the identification of a need, problem, or opportunity and culminates in the authorization of the project.

Key activities include:

- Developing the project charter, which formally authorizes the project and includes preliminary project requirements, budget, and timeline.

- Identifying stakeholders and understanding their expectations and influence on the project.

- Defining initial resources, roles, and responsibilities.

During this phase, the project’s broad outlines are established, including its scope, objectives, and significance. This phase lays the groundwork for the project, requiring a clear understanding of the project’s goals and the support it needs from stakeholders.

Planning Phase

The planning phase sets the foundation for how the project will be executed, monitored, and controlled. It involves:

- Developing a detailed project management plan, encompassing scope, schedule, cost, quality, resource, communication, risk, and procurement management plans.

- Establishing the project’s scope through detailed requirements and deliverables.

- Creating schedules and budgets that outline how the project will be executed within the set constraints.

This phase requires meticulous attention to detail, as it sets the trajectory for the entire project. It includes defining how to measure project performance and ensure alignment with the project’s objectives. The planning phase is critical for setting clear, actionable steps and allocating resources efficiently.

Executing Phase

The executing phase is where plans are put into action. This phase includes:

- Directing and managing project work to produce the project’s deliverables.

- Acquiring, developing, and managing the project team.

- Implementing quality management processes to ensure project deliverables meet the required standards.

Execution requires coordination among various project elements and stakeholders to ensure activities are carried out according to the project management plan. This phase often involves problem-solving and adjustments to stay aligned with project goals.

Monitoring and Controlling Phase

This phase involves tracking, reviewing, and regulating the progress and performance of the project. Key activities include:

- Measuring project performance to identify any project deviations.

- Implementing changes and corrective actions to ensure project alignment with the plan.

- Managing changes to the project scope, schedule, and costs.

Monitoring and controlling are continuous processes that ensure the project’s objectives are met. This phase requires constant vigilance to detect potential issues and implement solutions promptly.

Closing Phase

The closing phase finalizes all project activities across all process groups, formally closing the project. This includes:

- Finalizing all project work, including completing any remaining deliverables.

- Confirming the project’s scope and objectives were met.

- Conducting post-project evaluation to document lessons learned and release project resources.

Closure ensures the project is completed satisfactorily, stakeholders are informed, and resources are released. It’s a critical phase for reflecting on the project process and outcomes, aiming for continuous improvement.

Summary

- Initiating: Establish the project’s vision and authorization.

- Planning: Set detailed, actionable steps for project execution.

- Executing: Implement the project plan and produce deliverables.

- Monitoring and Controlling: Ensure project alignment with goals and implement corrective actions as needed.

- Closing: Formalize completion, evaluate performance, and document lessons learned.

Initiating a Project

In the initiation phase, we explore the foundational steps necessary to start a project, focusing on inputs, participants, key questions, and culminating in the development of the project charter.

Inputs to a Project

The initiation of a project begins with identifying the essential inputs. These inputs form the basis for understanding what the project aims to achieve and under what conditions. They include:

- Strategic Plans: The alignment of the project with the organization’s strategic goals.

- Policies, Procedures, and Practices: The organizational context within which the project will operate.

- Financial Plans/Feasibility Study: An assessment of the project’s economic viability.

- High-Level Specifications: Preliminary requirements or expectations of the project outcome.

- Prioritization and Selection Criteria: Guidelines for selecting and prioritizing projects.

- Assumptions & Constraints: Initial considerations and limitations impacting project planning.

Initiating a project requires a thorough analysis of strategic plans to ensure alignment with organizational goals. It involves evaluating financial feasibility, understanding organizational policies, and considering high-level specifications. Assumptions about industry trends, economic factors, and constraints such as timelines and funding are critical at this stage.

Project Participants

Key participants in the project initiation phase include:

- Owner/Sponsor: Responsible for financing and endorsing the project.

- Project Manager: Oversees planning, scheduling, and control of project activities.

- Architect/Engineer: Provides design services for the project.

- Prime/General Contractor: Executes the construction phase of the project.

In the early stages, the primary focus is on the Owner/Sponsor and the Project Manager. The Owner, or Sponsor, initiates the project, providing the necessary financial and organizational backing. The Project Manager plays a central role in organizing, planning, and moving the project forward, acting as the liaison among all participants.

What Questions Need to Be Answered?

Determining the project’s direction involves answering critical questions:

- Success Metrics: How will success be defined and measured?

- Project Purpose: What are the objectives of the project?

- Needs Fulfillment: What needs will the project address?

- Cost Estimates: What are the projected costs?

- Timeline: How long will the project take?

- Risks: What potential risks could impact the project?

Analyzing options involves a detailed examination of costs, schedules, risks, and benefits. It’s about making an educated decision on the most suitable path forward, factoring in constraints and assumptions, and weighing the pros and cons of different approaches.

The Project Charter

The culmination of the initiating phase is the creation of the Project Charter:

- Defines the project’s end results, scope, and how it aligns with organizational goals.

- Includes high-level budget and schedule estimates, along with identified risks and opportunities.

- Requires sign-off and funding approvals from the project sponsor, formally authorizing the project.

The Project Charter is a pivotal document that encapsulates the essence of the project initiation phase. It serves as a reference for all project stakeholders, outlining the project’s purpose, expected outcomes, budget, timeline, and key risks. It ensures that the project has a clear direction and the backing it needs to proceed to the planning phase.

Key Takeaways

- Inputs: The foundational information needed to start planning a project, including strategic alignment and feasibility.

- Participants: Key roles include the Owner/Sponsor, Project Manager, Architect/Engineer, and Prime/General Contractor.

- Key Questions: Critical considerations that guide the selection of the project, including purpose, costs, timeline, and risks.

- Project Charter: The document that formalizes the project’s initiation, outlining scope, budget, and schedule, and obtaining necessary approvals.

The Life Cycle of a Building

The construction process is only a small portion of the overall life of that building. Many buildings that are constructed last to be 100 years old or more. Because of this, it is important to understand the entire life cycle of our building project before we can begin to discuss the individual construction process.

The Life Cycle of a Building Project

The acquisition of a constructed facility usually represents a major capital investment, whether its owner happens to be an individual, a private corporation or a public agency. Since the commitment of resources for such an investment is motivated by market demands or perceived needs, the facility is expected to satisfy certain objectives within the constraints specified by the owner and relevant regulations. Except for the speculative housing market, where the residential units may be sold as built by the real estate developer, most constructed facilities are custom-made in consultation with the owners. A real estate developer may be regarded as the sponsor of building projects, as much as a government agency may be the sponsor of a public project and turns it over to another government unit upon its completion. From the viewpoint of project management, the terms “owner” and “sponsor” are synonymous because both have the ultimate authority to make all important decisions. Since an owner is essentially acquiring a facility on a promise in some form of agreement, it will be wise for any owner to have a clear understanding of the acquisition process to maintain firm control of the quality, timeliness and cost of the completed facility.

A project proceeds through a lifecycle. A facility is planned, designed, constructed, and operated. From the perspective of an owner, the project life cycle for a constructed facility may be illustrated schematically in Figure 2.2. Essentially, a project is conceived to meet market demands or needs in a timely fashion. Various possibilities may be considered in the conceptual planning stage, and the technological and economic feasibility of each alternative will be assessed and compared to select the best possible project.

The financing schemes for the proposed alternatives must also be examined, and the project will be programmed concerning the timing for its completion and for available cash flows. After the scope of the project is clearly defined, a detailed engineering design will provide the blueprint for construction, and the definitive cost estimate will serve as the baseline for cost control. In the procurement and construction stage, the delivery of materials and the erection of the project on-site must be carefully planned and controlled. After the construction is completed, there is usually a brief period of start-up or shake-down of the constructed facility when it is first occupied. Finally, the management of the facility is turned over to the owner for full occupancy until the facility lives out its useful life and is designated for demolition or conversion.

Of course, the stages of development in Figure 2.2 may not be strictly sequential. Some of the stages require iteration, and others may be carried out in parallel or with overlapping time frames, depending on the nature, size and urgency of the project. Furthermore, an owner may have in-house capacities to handle the work in every stage of the entire process, or it may seek professional advice and services for the work in all stages. Understandably, most owners choose to handle some of the work in-house and to contract outside professional services for other components of the work as needed. By examining the project life cycle from an owner’s perspective we can focus on the proper roles of various activities and participants in all stages regardless of the contractual arrangements for different types of work.

In the United States, for example, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has in-house capabilities to deal with planning, budgeting, design, construction and operation of waterway and flood control structures. Other public agencies, such as state transportation departments, are also deeply involved in all phases of a construction project. In the private sector, many large firms such as DuPont, Exxon, and IBM are adequately staffed to carry out most activities for plant expansion. All these owners, both public and private, use outside agents to a greater or lesser degree when it becomes more advantageous to do so.

This lifecycle, and the importance of taking a lifecycle perspective on projects, has sometimes been referenced as a Cradle-To-Grave perspective. From a lifecycle perspective, all materials and systems should be evaluated relative to their value in supporting the lifecycle goals of a building or facility. This process is often very complex; however, it can be decomposed into several stages as indicated by the general outline in Figure 2.2.The solutions at various stages are then integrated to obtain the final outcome. Some have expanded upon the concept of Cradle to Grave by considering the lifecycle as a continuous process and proposing a reference to Cradle to Cradle (C2C). C2C emphasizes the need to consider the reuse or recycling of products that are used within the delivery of a building. Although each stage requires different expertise, it usually includes both technical and managerial activities in the knowledge domain of the specialist. The owner may choose to decompose the entire process into more or less stages based on the size and nature of the project, and thus obtain the most efficient result in implementation. Very often, the owner retains direct control of work in the planning and programming stages, but increasingly outside planners and financial experts are used as consultants because of the complexities of projects. Since the operation and maintenance of a facility will go on long after the completion and acceptance of a project, it is usually treated as a separate problem except in the consideration of the life cycle cost of a facility. All stages from conceptual planning and feasibility studies to the acceptance of a facility for occupancy may be broadly lumped together and referred to as the Design/Construct process, while the procurement and construction alone are traditionally regarded as the province of the construction industry.

Another approach to the overall life cycle is a 4-Stage approach, which includes Planning, Design, Construction, then Operations & Maintenance. (Figure 2.3)

Planning Phase

During the planning stage, the Owner of the facility will need to define their project needs, identify the general budget and schedule, and potentially identify a site for the building. The owner may employ the services of an architect, contract developer, or other professional to help them define their needs and identify the resource requirements. The final outcome of the planning phase is a ‘Program’, or in some countries, a ‘Brief’, which clearly defines the owner’s needs and a plan to design and construct the facility. They will also need to identify and sometimes purchase a site for the facility.

Design Phase

Within the design phase, a designer will interpret the needs of the owner into a design for the facility which is to a level of detail that it can be built.

The design phase is frequently divided into three levels of design:

- Schematic Design (SD): Perform an evaluation of the owner’s needs, and develop an initial design concept. Typically, the industry has considered this level of design to be approximately 30% complete.

- Design Development (DD): Expand the initial concept to define the systems that will be used and general materials. Typically, this has been considered approximately 60% design completion.

- Construction Documents (CD): Finalize the design details to a level that they can be built. Complete all design specifications and construction drawings.

The full scope of these design tasks will typically be defined within the contract with the designer (or integrated team if using a more integrated delivery approach). To see the typical definitions of the scopes within these phases, you can view the typical Owner–Architect Agreement from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) within their AIA B101 document .

Construction Phase

Within the construction phase, a contractor will lead the assembly and construction of the facility. This will include the procurement of all the elements needed to build the facility, including arranging for the elements to be transported to the site. After arrival, the building component will be assembled on-site and tested to ensure the appropriate level of quality. The constructed facility will also require any inspections by governing authorities to ensure that it is safe to use for its intended purpose. For a building project, the primary construction phase typically ends when the contractor obtains a ‘Certificate of Occupancy’. The Certificate of Occupancy is issued by the local governing authority or code office, and it certifies that the building complies with the codes and requirements and that the owner can occupy the building.

Operations & Maintenance Phase

The Operations & Maintenance (O&M) phase is typically the longest phase within the facility lifecycle. In this phase, the owner will use the facility for its intended purpose, and they will need to operate and maintain the functionality of the facility. In some research, up to 80% of the entire lifecycle cost of a facility is spent in the operations phase. Activities that occur within the phase include the maintenance of equipment, the replacement of materials and equipment that require replacement, and minor renovations to allow for revisions of facility use. This phase is also sometimes referred to as Facility Management (FM), and an owner may perform the facility management services with their own internal employees, or they may hire a 3rd party FM service provider.

Owners must recognize that there is no single best approach to organizing project management throughout a project’s life cycle. All organizational approaches have advantages and disadvantages, depending on the knowledge of the owner in construction management as well as the type, size and location of the project. The owner needs to be aware of the approach which is most appropriate and beneficial for a particular project. In making choices, owners should be concerned with the life cycle costs of constructed facilities rather than simply the initial construction costs.

Saving small amounts of money during construction may not be worthwhile if the result is much larger operating costs or not meet the functional requirements for the new facility satisfactorily. Thus, owners must be very concerned with the quality of the finished product as well as the cost of construction itself. Since facility operation and maintenance is a part of the project life cycle, the owners’ expectation to satisfy investment objectives during the project life cycle will require consideration of the cost of operation and maintenance. Therefore, the facility’s operating management should also be considered as early as possible, just as the construction process should be kept in mind at the early stages of planning and programming.

| Design Stage | Decisions to Make | Useful Expertise | Example |

| Pre-design | Massing, orientation, structural considerations | Structural engineer | Considering structural systems based on environmental goals |

| Schematic design | Site and floor plans, initial assembly design, mechanical systems | Mechanical engineer, structural engineer, building science specialist | Comparing environmental costs and benefits of different insulation materials |

| Design development & construction documents | Detailed site plan, elevations, and sections; material specifications | Specifications consultant | Choosing lower-impact interior finishes |

| After construction | Certification submittals: post-design lessons learned | LCA expert | Calculating carbon offset for Living Building Challenge |

Test your Knowledge!

In the context of the project management life cycle, which phase is critical for laying the groundwork of a project, involving the development of a project charter and identifying stakeholders?

Lesson 2: The Initiating Phase

Your role in the construction project determines when and how you become involved. As the owner’s representative, you’re likely to join the project during the Initiating Phase. It’s important to grasp the essentials of this phase, especially how the project charter comes to be. On the other hand, as a general contractor, your participation might start later, during the Planning or Execution Phases, depending on your contract. We’ll explore contract types in more detail later. For now, our focus is on understanding decision-making at this early stage. Understanding what the owner specifically wants is critical, as it influences the entire project’s direction from the outset.

Initiating Phase

The project initiation phase is the first phase within the project management life cycle, as it involves starting up a new project. Within the initiation phase, the business problem or opportunity is identified, a solution is defined, a project is formed, and a project team is appointed to build and deliver the solution to the customer. A business case is created to define the problem or opportunity in detail and identify a preferred solution for implementation.

The business case includes:

- A detailed description of the problem or opportunity with headings such as Introduction, Business Objectives, Problem/Opportunity Statement, Assumptions, and Constraints

- A list of the alternative solutions available

- An analysis of the business benefits, costs, risks, and issues

- A description of the preferred solution

- Main project requirements

- A summarized plan for implementation that includes a schedule and financial analysis

The project sponsor then approves the business case, and the required funding is allocated to proceed with a feasibility study. It is up to the project sponsor to determine if the project is worth undertaking and whether the project will be profitable to the organization. The completion and approval of the feasibility study trigger the beginning of the planning phase. The feasibility study may also show that the project is not worth pursuing and the project is terminated; thus the next phase never begins.

All projects are created for a reason. Someone identifies a need or an opportunity and devises a project to address that need. How well the project ultimately addresses that need defines the project’s success or failure. The success of your project depends on the clarity and accuracy of your business case and whether people believe they can achieve it. Whenever you consider past experience, your business case is more realistic; and whenever you involve other people in the business case’s development, you encourage their commitment to achieving it.

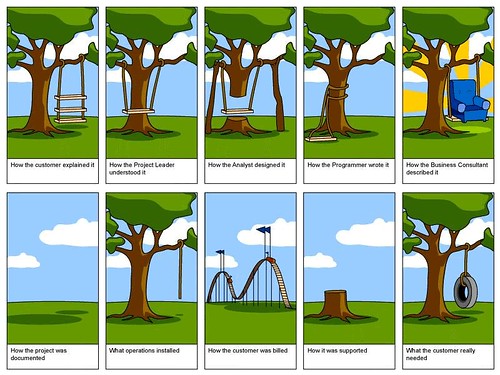

Often the pressure to get results encourages people to go right into identifying possible solutions without fully understanding the need or what the project is trying to accomplish. This strategy can create a lot of immediate activity, but it also creates significant chances for waste and mistakes if the wrong need is addressed. One of the best ways to gain approval for a project is to identify the project’s objectives and describe the need or opportunity for which the project will provide a solution. For most of us, being misunderstood is a common occurrence, something that happens daily. At the restaurant, the waiter brings us our dinner and we note that the baked potato is filled with sour cream, even though we expressly requested “no sour cream.” Projects are filled with misunderstandings between customers and project staff. What the customer ordered (or more accurately what they think they ordered) is often not what they get. The cliché is “I know that’s what I said, but it’s not what I meant.” Figure 2.6 demonstrates the importance of establishing clear objectives.

The need for establishing clear project objectives cannot be overstated. An objective or goal lacks clarity if, when shown to five people, it is interpreted in multiple ways. Ideally, if an objective is clear, you can show it to five people who, after reviewing it, hold a single view about its meaning. The best way to make an objective clear is to state it in such a way that it can be verified. Building in ways to measure achievement can do this. It is important to provide quantifiable definitions of qualitative terms.

Test your Knowledge!

During the Initiating Phase, a project manager must make several key decisions. Identify one crucial output from this phase that serves as formal authorization to begin the project.

To ensure the project’s objectives are achievable and realistic, they must be determined jointly by managers and those who perform the work. Realism is introduced because the people who will do the work have a good sense of what it takes to accomplish a particular task. In addition, this process assures some level of commitment on all sides: management expresses its commitment to support the work effort and workers demonstrate their willingness to do the work.

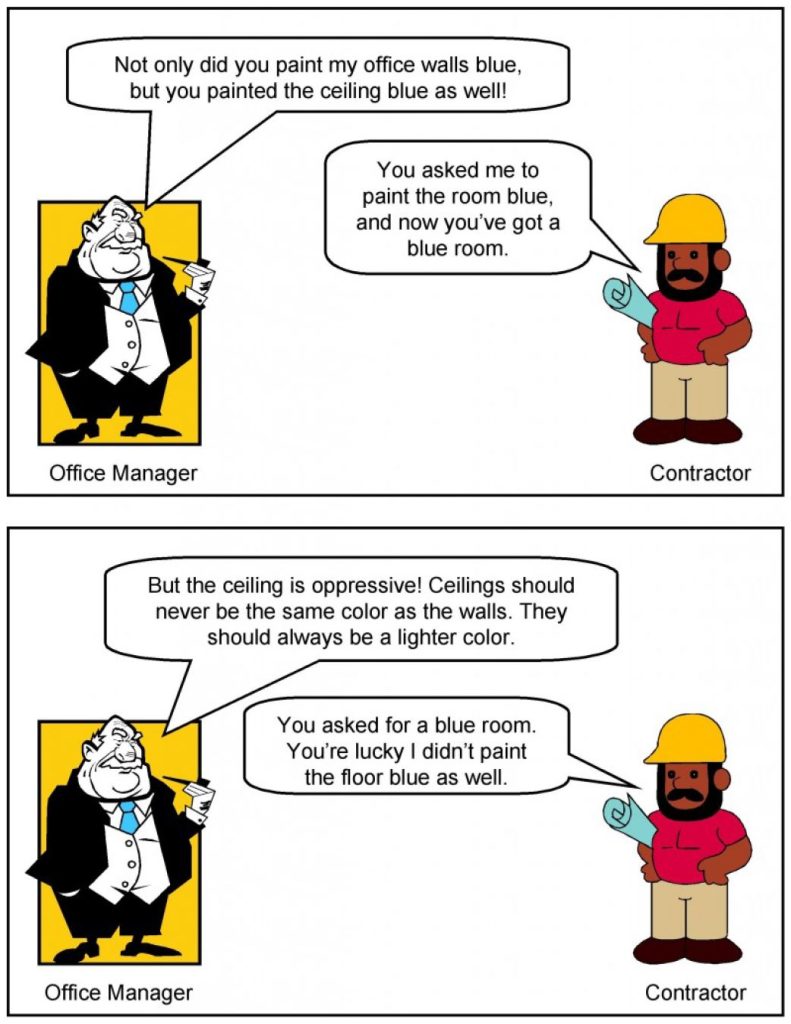

Imagine an office manager has contracted a painter to paint his office. His goal or objective is to have the office painted a pleasing blue color. Consider the conversation that occurs after the job is finished. (Figure 2.7)

This conversation highlights a common root of misunderstandings in projects: the critical need for clear objectives. The office manager’s instructions for painting the room were interpreted differently by the painter, leading to results that didn’t meet the office manager’s expectations. If the objectives had been articulated more precisely, the outcome might have matched the office manager’s vision. This underscores the importance of clear communication and detailed specifications from the outset.

In the Initiation phase, projects begin with the end objective/result in mind and then plans are produced and executed to achieve that end. This end or purpose is explicit and:

- Has consensus from all Stakeholders

- Clearly indicates how the project will contribute to the core business objectives or strategic objectives of the demand organization.

While projects can vary greatly in size and complexity from simple landscaping repairs to major acquisitions with design and construction, all projects require the following:

- A well-defined purpose and appropriate resources to achieve the objective

- A realistic, achievable schedule

- Adequate funding

The Initiation phase is made up of tasks typically performed before the project is officially approved. One of the key outputs of this phase, the project charter, is the document that officially approves and starts the project.

Assignment 2.1: 5 Critical Considerations

This reflection assignment is meant to explore a scenario and then differentiate between project management strategies. Granted, we don’t know much yet about analysis, but this process is happening at the beginning of a project and it is important to consider the steps we must take to decide on the best course of action for the project sponsor. Consider the following scenario.

Scenario

ABC Company is navigating a shift in their office space strategy due to changing work preferences post-COVID, with an increasing number of employees favoring remote and flexible working arrangements. Recognizing the need to adapt, the company’s strategic team has proposed two options: remodeling the existing office space or constructing a new one. As the appointed project manager, your task is to analyze these options and recommend a path forward.

Questions

As the project manager in the Initiating phase, you face several considerations in making your decision. Reflect on the following:

- Needs Assessment: Evaluate the specific needs of the company and its employees regarding office space. How do these needs align with the options of remodeling vs. building new?

- Cost Analysis: Consider the financial implications of both options. Which is more viable in the short term and the long term?

- Time Constraints: Assess the timeline for each option. Which approach meets the company’s timeline for making the transition?

- Risk Management: Identify potential risks associated with each option. How might these risks impact the decision-making process?

- Stakeholder Input: Consider the importance of stakeholder opinions, including employees and leadership, in the decision-making process. How will their input influence the choice between remodeling and building new?

Your task is to identify five critical considerations, steps, or tasks necessary for making an informed decision between the two options. How might someone else go about this task in the wrong way? What mistakes might they make?

Evaluation Criteria

Your reflection will be evaluated based on the following criteria:

- Identification of five key considerations, steps, tasks, or questions essential for making an informed decision between the two scenarios.

- Active engagement with at least two other posts, aiming to foster class connections and contribute to a deeper understanding of the project management process in the Initiating phase.

This activity is designed to enhance your ability to critically analyze project management scenarios and apply theoretical knowledge to practical situations. Your participation will help solidify your understanding of the initiating phase’s importance and how it shapes the direction of a project.

Lesson 3: Key Participants

Overview

Recognizing the significance of each person’s role is fundamental to a project’s success. It’s essential that these roles are clearly defined and that each participant understands how their specific responsibilities and decisions contribute to achieving the project’s objectives.

Selection of Professional Services

The owner of the project is the instigating party that gets the project financed, designed, and built. In the initiating stage of the project, they have either asked someone for options, or they are being presented with the options. They are typically also the project sponsor. The owner can be a public, private, or public-private partnership.

When an owner decides to seek professional services for the design and construction of a facility, he is confronted with a broad variety of choices. The type of services selected depends to a large degree on the type of construction and the experience of the owner in dealing with various professionals in the previous projects undertaken by the firm. Generally, several common types of professional services may be engaged either separately or in some combination by the owners.

Financial Planning Consultants

At the early stage of strategic planning for a capital project, an owner often seeks the services of financial planning consultants such as certified public accounting (CPA) firms to evaluate the economic and financial feasibility of the constructed facility, particularly with respect to various provisions of federal, state and local tax laws which may affect the investment decision. Investment banks may also be consulted on various options for financing the facility in order to analyze their long-term effects on the financial health of the owner organization.

Architectural and Engineering Firms

The architect, also known as the design professional, is the party or firm that will design the project. The firm may include engineering, or the Engineer(s) may be a second firm. Some organizations may have a close relationship with an Architect/Engineering firm and include them in the early conceptual process, or they may be brought in during the planning phase of a project.

Traditionally, the owner engages an architectural and engineering (A/E) firm or consortium as a technical consultant in developing a preliminary design. After the engineering design and financing arrangements for the project are completed, the owner will enter into a construction contract with a general contractor either through competitive bidding or negotiation. The general contractor will act as a constructor and/or a coordinator of a large number of subcontractors who perform various specialties for the completion of the project. The A/E firm completes the design and may also provide on-site quality inspection during construction. Thus, the A/E firm acts as the prime professional on behalf of the owner and supervises the construction to ensure satisfactory results. This practice is most common in building construction.

In the past two decades, this traditional approach has become less popular for a number of reasons, particularly for large-scale projects. The A/E firms, which are engaged by the owner as the prime professionals for design and inspection, have become more isolated from the construction process. This has occurred because of pressures to reduce fees to A/E firms, the threat of litigation regarding construction defects, and the lack of knowledge of new construction techniques on the part of architects and engineering professionals. Instead of preparing a construction plan along with the design, many A/E firms are no longer responsible for the details of construction nor do they provide periodic field inspections in many cases. As a matter of fact, such firms will place a prominent disclaimer of responsibilities on any shop drawings they may check, and they will often regard their representatives in the field as observers instead of inspectors. Thus, the A/E firm and the general contractor on a project often become antagonists who are looking after their own competing interests. As a result, even the constructability of some engineering designs may become an issue of contention. To carry this protective attitude to the extreme, the specifications prepared by an A/E firm for the general contractor often protect the interest of the A/E firm at the expense of the interests of the owner and the contractor.

In order to reduce the cost of construction, some owners introduce value engineering, which seeks to reduce the cost of construction by soliciting a second design that might cost less than the original design produced by the A/E firm. In practice, the second design is submitted by the contractor after receiving a construction contract at a stipulated sum, and the saving in cost resulting from the redesign is shared by the contractor and the owner. The contractor is able to absorb the cost of redesign from the profit in construction or to reduce the construction cost as a result of the re-design. If the owner had been willing to pay a higher fee to the A/E firm or to better direct the design process, the A/E firm might have produced an improved design which would cost less in the first place. Regardless of the merit of value engineering, this practice has undermined the role of the A/E firm as the prime professional acting on behalf of the owner to supervise the contractor.

Design/Construct Firms

A common trend in industrial construction, particularly for large projects, is to engage the services of a design/construction firm. By integrating design and construction management in a single organization, many of the conflicts between designers and constructors might be avoided. In particular, designs will be closely scrutinized for their constructability. However, an owner engaging a design/construction firm must ensure that the quality of the constructed facility is not sacrificed by the desire to reduce the time or the cost of completing the project. Also, it is difficult to make use of competitive bidding in this type of design/construction process. As a result, owners must be relatively sophisticated in negotiating realistic and cost-effective construction contracts.

One of the most obvious advantages of the integrated design/construction process is the use of phased construction for a large project. In this process, the project is divided up into several phases, each of which can be designed and constructed in a staggered manner. After the completion of the design of the first phase, construction can begin without waiting for the completion of the design of the second phase, etc. If proper coordination is exercised. the total project duration can be greatly reduced. Another advantage is to exploit the possibility of using the turnkey approach whereby an owner can delegate all responsibility to the design/construct firm which will deliver to the owner a completed facility that meets the performance specifications at the specified price.

Professional Construction Managers

In recent years, a new breed of construction managers (CM) has offered professional services from the inception to the completion of a construction project. These construction managers mostly come from the ranks of A/E firms or general contractors who may or may not retain dual roles in the service of the owners. In any case, the owner can rely on the service of a single prime professional to manage the entire process of a construction project. However, like the A/E firms of several decades ago, construction managers are appreciated by some owners but not by others. Before long, some owners find that the construction managers too may try to protect their own interest instead of that of the owners when the stakes are high.

It should be obvious to all involved in the construction process that the party which is required to take higher risk demands larger rewards. If an owner wants to engage an A/E firm on the basis of low fees instead of established qualifications, it often gets what it deserves; or if the owner wants the general contractor to bear the cost of uncertainties in construction such as foundation conditions, the contract price will be higher even if competitive bidding is used in reaching a contractual agreement. Without mutual respect and trust, an owner cannot expect that construction managers can produce better results than other professionals. Hence, an owner must understand their own responsibility and the risk they wish to assign to themselves and to other participants in the process.

Operation and Maintenance Managers

Although many owners keep a permanent staff for the operation and maintenance of constructed facilities, others may prefer to contract such tasks to professional managers. Understandably, it is common to find in-house staff for operation and maintenance in specialized industrial plants and infrastructure facilities, and the use of outside managers under contracts for the operation and maintenance of rental properties such as apartments and office buildings. However, there are exceptions to these common practices. For example, maintenance of public roadways can be contracted to private firms. In any case, managers can provide a spectrum of operation and maintenance services for a specified period by the terms of contractual agreements. Consequently, the owners can be spared the provision of in-house expertise to operate and maintain the facilities.

Facilities Management

As a logical extension for obtaining the best services throughout the project life cycle of a constructed facility, some owners and developers are receptive to adding strategic planning at the beginning and facility maintenance as a follow-up to reduce space-related costs in their real estate holdings. Consequently, some architectural/engineering firms and construction management firms with computer-based expertise, together with interior design firms, are offering such front-end and follow-up services in addition to the more traditional services in design and construction.

This spectrum of Facilities Management services is defined in the Engineering News-Record (ENR) as

“The discipline of planning, designing, constructing and managing space — in every type of structure from office buildings to process plants. It involves developing corporate facilities policy, long-range forecasts, real estate, space inventories, projects (through design, construction and renovation), building operation and maintenance plans and furniture and equipment inventories.” .

A common denominator of all firms entering into these new services is that they all have strong computer capabilities and heavy computer investments. In addition to the use of computers for aiding design and monitoring construction, the service includes the compilation of a computer record of building plans that can be turned over at the end of construction to the facilities management group of the owner. A computer database of facilities information makes it possible for planners in the owner’s organization to obtain overview information for long-range space forecasts, while the line managers can use as-built information such as lease/tenant records, utility costs, etc. for day-to-day operations.

Construction Contractors

Builders who supervise the execution of construction projects are traditionally referred to as contractors, or more appropriately called constructors. The general contractor coordinates various tasks for a project while the specialty contractors such as mechanical or electrical contractors perform the work in their specialties. Material and equipment suppliers often act as installation contractors; they play a significant role in a construction project since the conditions of delivery of materials and equipment affect the quality, cost, and timely completion of the project. It is essential to understand the operation of these contractors to deal with them effectively.

General Contractors

The prime contractor, or general contractor, is the firm that contracts directly with the owner for the construction of a project. This can happen as early as the planning stage in the case of Design-Build, or in the executing stage for other types of contracts such as Design-Bid-Build. We will get more into contract types later on. The function of a general contractor is to coordinate all tasks in a construction project. Unless the owner performs this function or engages a professional construction manager to do so, a good general contractor who has worked with a team of superintendents, specialty contractors, or subcontractors together for a number of projects in the past can be most effective in inspiring loyalty and cooperation. The general contractor is also knowledgeable about the labor force employed in construction. The labor force may or may not be unionized depending on the size and location of the projects. In some projects, no member of the workforce belongs to a labor union; in other cases, both union and non-union craftsmen work together in what is called an open shop, or all craftsmen must be affiliated with labor unions in a closed shop. Since labor unions provide hiring halls staffed with skilled journeymen who have gone through apprentice programs for the projects as well as serving as collective bargain units, an experienced general contractor will make good use of the benefits and avoid the pitfalls in dealing with organized labor.

Specialty Contractors

Specialty contractors include mechanical, electrical, foundation, excavation, and demolition contractors among others. They usually serve as subcontractors to the general contractor of a project. In some cases, legal statutes may require an owner to deal with various specialty contractors directly. In the State of New York, for example, specialty contractors, such as mechanical and electrical contractors, are not subjected to the supervision of the general contractor of a construction project and must be given separate prime contracts on public works. With the exception of such special cases, an owner will hold the general contractor responsible for negotiating and fulfilling the contractual agreements with the subcontractors.

Material and Equipment Suppliers

Major material suppliers include specialty contractors in structural steel fabrication and erection, sheet metal, ready mixed concrete delivery, reinforcing steel bar detailers, roofing, glazing etc. Major equipment suppliers for industrial construction include manufacturers of generators, boilers piping and other equipment. Many suppliers handle on-site installation to ensure that the requirements and contractual specifications are met. As more and larger structural units are prefabricated off-site, the distribution between specialty contractors and material suppliers becomes even less obvious.

The Role of Project Managers

The Project Manager organizes, plans, schedules, and controls all the work of the project and is responsible for getting the project completed within the time and cost limitations. They are usually the central point of contact for all facets of the project to bring together all the various participants’ efforts contributing to the construction process.

In the project life cycle, the most influential factors affecting the outcome of the project often reside in the early stages. At this point, decisions should be based on competent economic evaluation with due consideration for adequate financing, the prevalent social and regulatory environment, and technological considerations. Architects and engineers might specialize in planning, construction field management, or in operation, but as project managers, they must have some familiarity with all such aspects in order to sufficiently understand their role and be able to make competent decisions.

Since the 1970s, many large-scale projects have run into serious problems of management, such as cost overruns and long schedule delays. Actually, the management of megaprojects or super projects is not a practice peculiar to our time. Witness the construction of transcontinental railroads in the Civil War era and the construction of the Panama Canal at the turn of this century. Although the megaprojects of this generation may appear in greater frequency and present a new set of challenges, the problems are organizational rather than technical.

It is customary to think of engineering as a part of a trilogy, pure science, applied science and engineering. It needs to be emphasized that this trilogy is only one of a triad of trilogies into which engineering fits. This first is pure science, applied science and engineering; the second is economic theory, finance and engineering; and the third is social relations, industrial relations and engineering. Many engineering problems are as closely allied to social problems as they are to pure science.

As engineers progress in their careers, they frequently find themselves dedicating as much, if not more, time to planning, management, and addressing economic or social issues as they do to the traditional tasks of engineering design and analysis that are central to their education. The breadth of problems engineers can solve, encompassing both their technical and non-technical aspects, becomes the measure of their professional success.

A major challenge to effective construction management is overcoming the inertia and historical divisions between planners, designers, and constructors. Although technical skills in design and innovation are crucial, successful management also demands addressing the social, economic, and organizational factors influencing project outcomes. Engineers don’t need to master every management technique, but a foundational understanding is essential to foresee potential issues and collaborate effectively across disciplines.

The problem-solving skills of engineers who are creative in their engineering designs often translate well to innovative planning and management. Integrating both domains into education, with an emphasis on creativity over routine, enhances this partnership. A project manager grounded in the basics of engineering and management principles can adeptly adapt to new areas, becoming a potential leader. Conversely, a manager trained narrowly through rote learning risks stagnation, repeating the same level of experience without significant growth.

Choosing a skilled project manager with the authority to make critical decisions at various project stages is crucial for owners, regardless of the types of contractual agreements for implementing the project. Beyond technical knowledge, a project manager must exhibit leadership and manage complex interpersonal dynamics effectively. The true measure of a project manager’s skills lies in applying fundamental principles to novel and challenging situations, a necessity in the constantly evolving construction industry.

Organization of Project Participants

The top management of the owner sets the overall policy and selects the appropriate organization to take charge of a proposed project. Its policy will dictate how the project life cycle is divided among organizations and which professionals should be engaged. Decisions by the top management of the owner will also influence the organization to be adopted for project management. In general, there are many ways to decompose a project into stages. The most typical ways are:

- Sequential processing whereby the project is divided into separate stages and each stage is carried out successively in sequence.

- Parallel processing whereby the project is divided into independent parts such that all stages are carried out simultaneously.

- Staggered processing whereby the stages may be overlapping, such as the use of phased design-construct procedures for fast-track operation.

It should be pointed out that some decompositions may work out better than others, depending on the circumstances. In any case, the prevalence of decomposition makes the subsequent integration particularly important.

The critical issues involved in organization for project management are:

- How many organizations are involved?

- What are the relationships among the organizations?

- When are the various organizations brought into the project?

There are two basic approaches to organizing for project implementation, even though many variations may exist as a result of different contractual relationships adopted by the owner and builder. These basic approaches are divided along the following lines:

- Separation of organizations: Numerous organizations serve as consultants or contractors to the owner, with different organizations handling design and construction functions. Typical examples which involve different degrees of separation are:

- The traditional sequence of design and construction

- Professional construction management

- Integration of organizations: A single or joint venture consisting of a number of organizations with a single command undertakes both design and construction functions. Two extremes may be cited as examples:

- Owner-builder operation in which all work will be handled in-house by force account.

- Turnkey operation in which all work is contracted to a vendor which is responsible for delivering the completed project

Since construction projects may be managed by a spectrum of participants in a variety of combinations, the organization for the management of such projects may vary from case to case. On one extreme, each project may be staffed by existing personnel in the functional divisions of the organization on an ad-hoc basis as shown in Figure 2.8 until the project is completed. This arrangement is referred to as the matrix organization as each project manager must negotiate all resources for the project from the existing organizational framework. On the other hand, the organization may consist of a small central functional staff for the exclusive purpose of supporting various projects, each of which has its functional divisions as shown in Figure 2.9. This decentralized set-up is referred to as the project-oriented organization as each project manager has autonomy in managing the project. There are many variations of management style between these two extremes, depending on the objectives of the organization and the nature of the construction project. For example, a large chemical company with in-house staff for planning, design and construction of facilities for new product lines will naturally adopt the matrix organization. On the other hand, a construction company whose existence depends entirely on the management of certain types of construction projects may find the project-oriented organization particularly attractive. While organizations may differ, the same basic principles of management structure are applicable to most situations.

To illustrate various types of organizations for project management, we will consider two examples, the first one representing an owner organization while the second one representing the organization of a construction management consultant under the direct supervision of the owner.

Example 2.1: Matrix Organization of an Engineering Division

The Engineering Division of an Electric Power and Light Company has functional departments as shown in Figure 2.10. When small-scale projects such as the addition of a transmission tower or a sub-station are authorized, a matrix organization is used to carry out such projects. For example, in the design of a transmission tower, the professional skill of a structural engineer is most important. Consequently, the leader of the project team will be selected from the Structural Engineering Department while the remaining team members are selected from all departments as dictated by the manpower requirements. On the other hand, in the design of a new substation, the professional skill of an electrical engineer is most important. Hence, the leader of the project team will be selected from the Electrical Engineering Department.

Example 2.2: Example of Construction Management Consultant Organization

When the same Electric Power and Light Company in the previous example decided to build a new nuclear power plant, it engaged a construction management consultant to take charge of the design and construction completely. However, the company also assigned a project team to coordinate with the construction management consultant as shown in Figure 2.11.

Since the company eventually will operate the power plant upon its completion, its staff needs to monitor the design and construction of the plant. Such coordination allows the owner not only to assure the quality of construction but also to be familiar with the design to facilitate future operation and maintenance. Note the close direct relationships of various departments of the owner and the consultant. Since the project will last for many years before its completion, the staff members assigned to the project team are not expected to rejoin the Engineering Department but will probably be involved in the future operation of the new plant. Thus, the project team can act independently toward its designated mission.

Leadership and Motivation for the Project Team

The project manager, in the broadest sense of the term, is the most important person for the success or failure of a project. The project manager is responsible for planning, organizing and controlling the project. In turn, the project manager receives authority from the management of the organization to mobilize the necessary resources to complete a project.

The project manager must be able to exert interpersonal influence in order to lead the project team. The project manager often gains the support of his/her team through a combination of the following:

- Formal authority resulting from an official capacity that is empowered to issue orders.

- Reward and/or penalty power resulting from his/her capacity to dispense directly or indirectly valued organization rewards or penalties.

- Expert power is when the project manager is perceived as possessing special knowledge or expertise for the job.

- Attractive power because the project manager has a personality or other characteristics to convince others.

In a matrix organization, the members of the functional departments may be accustomed to a single reporting line in a hierarchical structure, but the project manager coordinates the activities of the team members drawn from functional departments. The functional structure within the matrix organization is responsible for priorities, coordination, administration, and final decisions pertaining to project implementation. Thus, there are potential conflicts between functional divisions and project teams. The project manager must be given the responsibility and authority to resolve various conflicts such that the established project policy and quality standards will not be jeopardized. When contending issues of a more fundamental nature are developed, they must be brought to the attention of a high level in management and be resolved expeditiously.

In general, the project manager’s authority must be clearly documented as well as defined, particularly in a matrix organization where the functional division managers often retain certain authority over the personnel temporarily assigned to a project.

The following principles should be observed:

- The interface between the project manager and the functional division managers should be kept as simple as possible.

- The project manager must gain control over those elements of the project which may overlap with functional division managers.

- The project manager should encourage problem-solving rather than role-playing of team members drawn from various functional divisions.

Activity 2.1: Stakeholder Identification

Title: Video-Journal Reflection on Green Community Park Development

Overview

This activity is designed as a reflective exercise where you will explore the complexities and impacts of the Green Community Park Development project through a video-journal format. Reflecting on the project will deepen your understanding of project planning, stakeholder engagement, and the broader social and environmental implications of such initiatives.

Activity Objectives:

- To analyze and articulate the significance of the Green Community Park Development project from multiple perspectives.

- To develop communication skills through the creation of a reflective video journal.

Materials Needed

- The project description for the Green Community Park Development (provided below).

- A device capable of recording video (e.g., smartphone, tablet, laptop).

- Access to basic video editing tools, if desired, for enhancing the presentation of your reflection.

Project: Green Community Park Development

Background

The city council has approved the development of a new community park in the downtown area, aiming to provide a green space for relaxation, community events, and environmental education. The park will feature walking trails, a playground, an open-air amphitheater, and interactive exhibits on local ecology. The project is expected to take 18 months, with a focus on sustainable design and community involvement.

Objective: To create a multi-use green space that enhances the quality of life for city residents, promotes environmental awareness, and encourages community engagement.

Instructions

Reflect on the Green Community Park Development project, considering its objectives, planned features, and potential impact on the community and environment. Think about the following questions to guide your reflection:

- What are the potential benefits of the project for the community and the environment?

- How might different stakeholders view this project? Consider at least three different stakeholder perspectives.

- What challenges might arise during the project’s development, and how could they be addressed?

- How does this project align with your understanding of sustainable development and community engagement?

Record Your Video-Journal

- Record a video journal entry discussing your thoughts and analyses of the project. Aim for a video length of 3-5 minutes.

- Organize your reflection to ensure it is coherent and engaging. You may want to briefly plan or script your main points to aid in this.

- (Optional) Edit your video to improve clarity or add visual aids that enhance your presentation.

Submit Your Reflection

- Ensure your video privacy settings allow it to be viewed.

Lesson 4: Stakeholder Management

Stakeholder Management

A project is successful when it achieves its objectives and meets or exceeds the expectations of the stakeholders. But who are the stakeholders? Stakeholders are individuals who either care about or have a vested interest in your project. They are the people who are actively involved with the work of the project or have something to either gain or lose as a result of the project. When you manage a project to add lanes to a highway, motorists are stakeholders who are positively affected. However, you negatively affect residents who live near the highway during your project (with construction noise) and after your project with far-reaching implications (increased traffic noise and pollution).

**Note: Key stakeholders can make or break the success of a project. Even if all the deliverables are met and the objectives are satisfied, if your key stakeholders aren’t happy, nobody’s happy. **

The project sponsor, generally an executive in the organization with the authority to assign resources and enforce decisions regarding the project, is a stakeholder. The customer, subcontractors, suppliers, and sometimes even the government are stakeholders. The project manager, project team members, and the managers from other departments in the organization are stakeholders as well. It’s important to identify all the stakeholders in your project upfront. Leaving out important stakeholders or their department’s function and not discovering the error until well into the project could be a project killer.

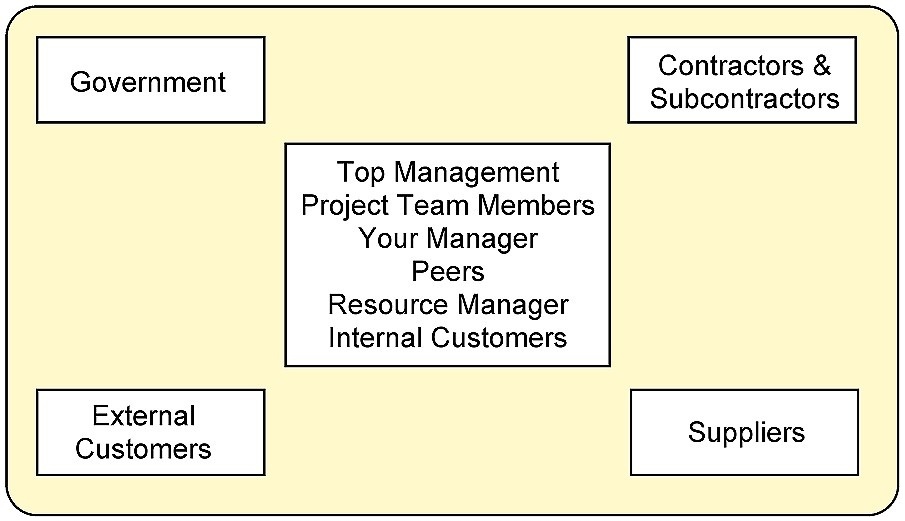

Figure 2.12 shows a sample of the project environment featuring the different kinds of stakeholders involved in a typical project. A study of this diagram confronts us with a couple of interesting facts.

- In a project, there are both internal and external stakeholders.

- Internal stakeholders may include top management, project team members, you manager, peers, resource manager, and internal customers.

- External stakeholders may include external customers, government, contractors and subcontractors, and suppliers.

- The number of stakeholders that project managers must deal with ensures that they will have a complex job guiding their projects through the lifecycle. Problems with any of these members can derail the project.

- The diagram shows that project managers have to deal with people external to the organization as well as the internal environment, certainly more complex than what a manager in an internal environment faces.

- For example, suppliers who are late in delivering crucial parts may blow the project schedule. To compound the problem, project managers generally have little or no direct control over any of these individuals.

Project Stakeholders

Top Management

Top management typically encompasses the highest-ranking officials within a company, including roles such as the president, vice presidents, directors, division managers, and members of the corporate operating committee. These individuals are instrumental in steering the company’s strategic direction and overseeing its growth and development.

Influence of Top Management on Projects

Advantages

- Support from the Upper Echelon: With the endorsement of top management, project managers often find it easier to mobilize the best available resources. This support can significantly enhance the recruitment of top-tier staff and the acquisition of necessary materials and resources.

- Increased Visibility: Projects that garner attention from top management tend to elevate the project manager’s profile within the company, offering a platform to demonstrate capability and expertise.

Challenges

- High Stakes: When projects are highly visible, they are under greater scrutiny. A failure, therefore, can be particularly conspicuous, drawing attention from across the organization.

- Significant Risks: Large and costly projects carry substantial risks. In the event of underperformance, the implications of failure are magnified compared to those of a smaller-scale, less visible project.

Top management may include the president of the company, vice presidents, directors, division managers, the corporate operating committee, and others. These people direct the strategy and development of the organization.

Some suggestions for dealing with top management are:

- Develop in-depth plans and major milestones that must be approved by top management during the planning and design phases of the project.

- Ask top management associated with your project for their information reporting needs and frequency.

- Develop a status reporting methodology to be distributed on a scheduled basis.

- Keep them informed of project risks and potential impacts at all times.

The Project Team

The project team is made up of those people dedicated to the project or borrowed on a part-time basis. As a project manager, you need to provide leadership, direction, and above all, support to team members as they go about accomplishing their tasks. Working closely with the team to solve problems can help you learn from the team and build rapport. Showing your support for the project team and for each member will help you get their support and cooperation.

Here are some difficulties you may encounter in dealing with project team members:

- Because project team members are borrowed and they don’t report to you, their priorities may be elsewhere.

- They may be juggling many projects as well as their full-time job and have difficulty meeting deadlines.

- Personality conflicts may arise. These may be caused by differences in social style or values or they may be the result of some bad experience when people worked together in the past.

- You may find out about missed deadlines when it is too late to recover.

Managing project team members requires interpersonal skills. Here are some suggestions that can help:

- Involve team members in project planning.

- Arrange to meet privately and informally with each team member at several points in the project, perhaps for lunch or coffee.

- Be available to hear team members’ concerns at any time.

- Encourage team members to pitch in and help others when needed.

- Complete a project performance review for team members.

Your Manager

Typically the boss decides what the assignment is and who can work with the project manager on projects. Keeping your manager informed will help ensure that you get the necessary resources to complete your project.

If things go wrong on a project, it is nice to have an understanding and supportive boss to go to bat for you if necessary. By supporting your manager, you will find your manager will support you more often.

- Find out exactly how your performance will be measured.

- When unclear about directions, ask for clarification.

- Develop a reporting schedule that is acceptable to your boss.

- Communicate frequently.

Peers

Peers are people who are at the same level in the organization as you and may or may not be on the project team. These people will also have a vested interest in the product. However, they will have neither the leadership responsibilities nor the accountability for the success or failure of the project that you have.

Your relationship with peers can be impeded by:

- Inadequate control over peers

- Political maneuvering or sabotage

- Personality conflicts or technical conflicts

- Envy because your peer may have wanted to lead the project

- Conflicting instructions from your manager and your peer’s manager

Peer support is essential. Since most of us serve our self-interest first, you may need to do some investigating, selling, influencing, and/or politicking. To ensure you have cooperation and support from your peers:

- Get the support of your project sponsor or top management to empower you as the project manager with as much authority as possible. It’s important that the sponsor makes it clear to the other team members that their cooperation on project activities is expected.

- Confront your peer if you notice a behavior that seems dysfunctional, such as bad-mouthing the project.

- Be explicit in asking for full support from your peers. Arrange for frequent review meetings.

- Establish goals and standards of performance for all team members.

Resource Managers

Because project managers are in the position of borrowing resources, other managers control their resources. So their relationships with people are especially important. If their relationship is good, they may be able to consistently acquire the best staff and the best equipment for their projects. If relationships aren’t good, they may find themselves not able to get good people or equipment needed on the project.

Internal Customers

Internal customers are individuals within the organization who are customers for projects that meet the needs of internal demands. The customer holds the power to accept or reject your work. Early in the relationship, the project manager will need to negotiate, clarify, and document project specifications and deliverables. After the project begins, the project manager must stay tuned in to the customer’s concerns and issues and keep the customer informed.

Common stumbling blocks when dealing with internal customers include:

- A lack of clarity about precisely what the customer wants

- A lack of documentation for what is wanted

- A lack of knowledge of the customer’s organization and operating characteristics

- Unrealistic deadlines, budgets, or specifications requested by the customer

- Hesitancy of the customer to sign off on the project or accept responsibility for decisions

- Changes in project scope

To meet the needs of the customer, client, or owner, be sure to do the following:

- Learn the client organization’s buzzwords, culture, and business.

- Clarify all project requirements and specifications in a written agreement.

- Specify a change procedure.

- Establish the project manager as the focal point of communications in the project organization.

External customers

External customers are the customers when projects could be marketed to outside customers. In the case of Ford Motor Company, for example, the external customers would be the buyers of the automobiles. If you are managing a project at your company for Ford Motor Company, they will be your external customer.

Government

Project managers working in certain heavily regulated environments (e.g., pharmaceutical, banking, or military industries) will have to deal with government regulators and departments. These can include all or some levels of government from municipal, provincial, federal, to international.

Contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers

There are times when organizations don’t have the expertise or resources available in-house, and work is farmed out to contractors or subcontractors. This can be a construction management foreman, network consultant, electrician, carpenter, architect, or anyone who is not an employee. Managing contractors or suppliers requires many of the skills needed to manage full-time project team members.

Any number of problems can arise with contractors or subcontractors:

- Quality of the work

- Cost overruns

- Schedule slippage

Many projects depend on goods provided by outside suppliers. This is true for example of construction projects where lumber, nails, bricks, and mortar come from outside suppliers. If the supplied goods are delivered late or are in short supply or of poor quality or if the price is greater than originally quoted, the project may suffer.

Depending on the project, managing contractor and supplier relationships can consume more than half of the project manager’s time. It is not purely intuitive; it involves a sophisticated skill set that includes managing conflicts, negotiating, and other interpersonal skills.

Politics of Projects

Many times, project stakeholders have conflicting interests. It’s the project manager’s responsibility to understand these conflicts and try to resolve them. It’s also the project manager’s responsibility to manage stakeholder expectations. Be certain to identify and meet with all key stakeholders early in the project to understand all their needs and constraints.

Project managers are somewhat like politicians. Typically, they are not inherently powerful or capable of imposing their will directly on coworkers, subcontractors, and suppliers. Like politicians, if they are to get their way, they have to exercise influence effectively over others. On projects, project managers have direct control over very few things; therefore their ability to influence others – to be a good politician – may be very important

Here are a few steps a good project politician should follow. However, a good rule is that when in doubt, stakeholder conflicts should always be resolved in favor of the customer.

Assess the environment

Identify all the relevant stakeholders. Because any of these stakeholders could derail the project, you need to consider their particular interest in the project.

- Once all relevant stakeholders are identified, try to determine where the power lies.

- In the vast cast of characters, who counts most?

- Whose actions will have the greatest impact?

Identify goals

After determining who the stakeholders are, identify their goals.

- What is it that drives them?

- What is each after?

- Are there any hidden agendas or goals that are not openly articulated?

- What are the goals of the stakeholders who hold the power? These deserve special attention.

Define the problem

- The facts that constitute the problem should be isolated and closely examined.