4 Module Four: Cost Estimating and Procurement

Module Four: Cost Estimating and Procurement

Module Learning Objectives

- Identify the basics elements of cost estimating. (CLO 2)

- Recall the estimating process for a construction project. (CLO 2)

- Distinguish between cost estimation types. (CLO 2)

- Compare contract types and their uses. (CLO 2)

- Evaluate when to use different contract types assuming conditions, risk, pricing, and timing. (CLO 2)

- Discuss the contrasting demands of cost, time, and quality for a project. (CLO 2)

Module Essential Questions

- What are the fundamental elements involved in cost estimating, and how do they contribute to accurate project budgeting and planning? (CLO 2)

- Can you outline the steps involved in the estimating process for a construction project, and how does each step ensure the accuracy and reliability of cost estimates? (CLO 2)

- How do different types of cost estimation vary, and what factors influence the choice of estimation method for a particular construction project? (CLO 2)

- What are the key characteristics of various contract types used in construction projects, and how are they tailored to suit different project requirements and objectives? (CLO 2)

- When considering conditions, risk, pricing, and timing, how can you determine the most suitable contract type for a given construction project, and what factors should be taken into account during this evaluation process? (CLO 2)

- How do the competing priorities of cost, time, and quality impact decision-making in construction projects, and what strategies can be employed to balance these demands effectively? (CLO 2)

Bridge-In

Two of the most important constraints in a project are cost and schedule. In the previous module, we discussed scope and schedule. In this module, we will be discussing estimating as it relates to the construction project and its importance in the planning phase. Detailed, accurate estimates are a critical part of construction, and professional estimators are in demand. Without accurate estimates, construction managers can’t build budgets, get approvals, or hire workers. Without an approved budget, the project will never move forward into the Executing phase. In this module, we’re taking our project roadmap and that customer’s dream and starting to turn it into something tangible for them. We will walk through the types of construction delivery and how to choose the right one for our construction project. From here we’ll look at the types of contracts used to implement each construction delivery method, as well as the bidding and procurement processes. These three things (project delivery method, procurement method, and contract model) are the three key decisions in construction bidding.

Lesson 1: Cost Estimating for Construction

This video covers the basics of cost estimating and the estimating process for a construction project. We aren’t going to make you expert estimators overnight, but you should gain knowledge to improve your understanding of what goes on during this project process

In this module, we’ll delve into why estimating is crucial for the success of any construction project, the different types of estimates you’ll encounter, the estimating process, and the legal and ethical considerations you must be aware of.

The Importance of Estimating

Estimating: A Critical Competency

Estimating in construction involves determining the expected quantities, and costs of materials, labor, and equipment necessary for a project. It’s the foundation upon which successful bidding and project execution rest.

Significance of accurate estimating:

- Key to Successful Bidding: Accurate estimates allow construction companies to bid competitively while ensuring profitability.

- Avoiding Losses: Overestimates can result in lost work opportunities, while underestimates can lead to financial losses.

- Efficiency and Resource Management: Precise estimates help prevent material wastage, delays, and unnecessary costs.

- Interactive Element Suggestion: An interactive quiz assessing the consequences of inaccurate estimating.

The Consequences of Inaccurate Estimating

- Loss of Work: Overestimating the costs could make your bid noncompetitive.

- Financial Loss: Underestimating leads to budget overruns, affecting profitability.

- Project Delays: Inaccurate quantity estimates can cause delays and increase project costs.

Types of Estimates

- Preliminary/Budget Estimate: Used in early project stages for budgeting and planning. It’s based on limited information and scope.

- Bid/Final Estimate: Detailed, based on complete project designs and specifications. It’s used for submitting project bids.

The Estimating Process

The estimating process includes several critical steps, from initial planning to post-bid review:

- Planning the Bid: Identifying project scope, preparing the schedule, and assigning tasks.

- Pre-Bid Process: Engaging with subcontractors, performing quantity takeoffs, and calculating overhead.

- Bid-Day Items: Finalizing the documentation, pricing, and reviewing for errors.

- Post-Bid Review: Analyzing the bidding process, regardless of win or loss, to refine future estimates.

Legal and Ethical Issues

The Significance of Integrity

The integrity of the estimator reflects directly on the company’s reputation. Adhering to ethical standards, protecting confidential information, and respecting trade secrets are paramount.

Ethics in Estimating

- Involves following a set of principles that guide professional conduct.

- Handling Confidential Information: Ensuring the security of sensitive company data and estimating practices.

- Interactive Element Suggestion: Scenario-based questions where students decide on the best ethical course of action.

Cost Estimating

Construction cost estimating is both an art and a science. To be an effective estimator, you need to be able to interpret a facility design and visualize and plan the approach toward building the facility. The best estimators are also very good at understanding previous construction costs and interpreting the conditions that will add or reduce future costs.

Many smaller companies have an estimator/project managers that have the responsibility to estimate the cost of potential projects, and when a new project is brought in, the estimator becomes the project manager for the project, as well as estimating new potential projects. As companies become larger and more sophisticated, estimating becomes a specialty area within the company, and when new projects are acquired, the estimator hands the project off to a project manager and continues to focus on estimating new projects. In this case, the project manager will still be involved in estimating such things as change orders and claims, but the primary focus is to effectively manage the project at hand. The focus here is the project manager of larger companies, rather than the estimator/project manager of smaller ones.

When a project manager is assigned to a recently acquired project, one of the first tasks is to become thoroughly familiar with the project, including the estimate. There will be a hand-off meeting between the estimator and the project manager, and from then on the project manager takes responsibility for the project, including the estimate. The project manager sets up the cost system to document and track costs throughout the project. The project manager will also make estimates of work accomplished as a basis for monthly pay requests and, as previously indicated when changes come up, will estimate the cost of those changes as the basis to negotiate change orders.

Construction cost estimates (‘estimates’) are created at many different points in time throughout a project. The owner may develop very early feasibility estimates to determine if a project is economically viable. A designer or construction manager may develop a series of progressively detailed estimates during the design process to ensure that the project is being designed to the owner’s budget. A general contractor or trade contractor will develop estimates to determine their bid or budget values for a project. There may be multiple estimates developed to determine the impact of various design options or develop a cost estimate for a design change during the construction process.

Costs Associated with Constructed Facilities

The costs of a constructed facility to the owner include both the initial capital cost and the subsequent operation and maintenance costs. Each of these major cost categories consists of several cost components.

The capital cost for a construction project includes the expenses related to the initial establishment of the facility:

- Land acquisition, including assembly, holding and improvement

- Planning and feasibility studies

- Architectural and engineering design

- Construction, including materials, equipment and labor

- Field supervision of construction

- Construction Financing

- Insurance and taxes during construction

- Owner’s general office overhead

- Equipment and furnishings not included in construction

- Inspection and testing

The operation and maintenance cost in subsequent years over the project life cycle includes the following expenses:

- Land rent, if applicable

- Operating staff

- Labor and material for maintenance and repairs

- Periodic renovations

- Insurance and taxes

- Financing costs

- Utilities

- Owner’s other expenses

The magnitude of each of these cost components depends on the nature, size and location of the project as well as the management organization, among many considerations. The owner is interested in achieving the lowest possible overall project cost that is consistent with its investment objectives.

Design professionals and construction managers need to realize that while the construction cost may be the single largest component of the capital cost, other cost components are not insignificant. For example, land acquisition costs are a major expenditure for building construction in high-density urban areas, and construction financing costs can reach the same order of magnitude as the construction cost in large projects such as the construction of nuclear power plants.

From the owner’s perspective, it is equally important to estimate the corresponding operation and maintenance cost of each alternative for a proposed facility to analyze the life cycle costs. The large expenditures needed for facility maintenance, especially for publicly owned infrastructure, are reminders of the neglect in the past to consider fully the implications of operation and maintenance costs in the design stage.

In most construction budgets, there is an allowance for contingencies or unexpected costs occurring during construction. This contingency amount may be included within each cost item or be included in a single category of construction contingency. The amount of contingency is based on historical experience and the expected difficulty of a particular construction project.

For example, one construction firm makes estimates of the expected cost in five different areas:

- Design development changes,

- Schedule adjustments,

- General administration changes (such as wage rates),

- Differing site conditions for those expected, and

- Third-party requirements imposed during construction, such as new permits.

Contingent amounts not spent for construction can be released near the end of construction to the owner or to add additional project elements.

Approaches to Cost Estimation

Cost estimating is one of the most important steps in project management. A cost estimate establishes the baseline of the project cost at different stages of development of the project. A cost estimate at a given stage of project development represents a prediction provided by the cost engineer or estimator based on available data. According to the American Association of Cost Engineers, cost engineering is defined as that area of engineering practice where engineering judgment and experience are utilized in the application of scientific principles and techniques to the problem of cost estimation, cost control and profitability.

Virtually all cost estimation is performed according to one or some combination of the following basic approaches:

- Production function

- In microeconomics, the relationship between the output of a process and the necessary resources is referred to as the production function. In construction, the production function may be expressed by the relationship between the volume of construction and a factor of production such as labor or capital.

- A production function relates the amount or volume of output to the various inputs of labor, material and equipment. For example, the amount of output Q may be derived as a function of various input factors x1, x2, …, xn by means of mathematical and/or statistical methods. Thus, for a specified level of output, we may attempt to find a set of values for the input factors to minimize the production cost. The relationship between the size of a building project (expressed in square feet) to the input labor (expressed in labor hours per square foot) is an example of a production function for construction.

- Empirical cost inference

- Empirical estimation of cost functions requires statistical techniques which relate the cost of constructing or operating a facility to a few important characteristics or attributes of the system. The role of statistical inference is to estimate the best parameter values or constants in an assumed cost function. Usually, this is accomplished through regression analysis techniques.

- Unit Costs for Bill of Quantities

- A unit cost is assigned to each of the facility components or tasks as represented by the bill of quantities. The total cost is the summation of the products of the quantities multiplied by the corresponding unit costs.

- The unit cost method is straightforward in principle but quite laborious in application:

- The initial step is to break down or disaggregate a process into several tasks. Collectively, these tasks must be completed for the construction of a facility.

- Once these tasks are defined and quantities representing these tasks are assessed, a unit cost is assigned to each and then the total cost is determined by summing the costs incurred in each task.

- The level of detail in decomposing into tasks will vary considerably from one estimate to another.

- Allocation of Joint Costs

- Allocations of cost from existing accounts may be used to develop a cost function of an operation.

- The basic idea in this method is that each expenditure item can be assigned to particular characteristics of the operation.

- Ideally, the allocation of joint costs should be causally related to the category of basic costs in an allocation process. In many instances, however, a causal relationship between the allocation factor and the cost item cannot be identified or may not exist.

- For example, in construction projects, the accounts for basic costs may be classified according to labor, material, construction equipment, construction supervision, and general office overhead. These basic costs may then be allocated proportionally to various tasks which are subdivisions of a project.

Types of Construction Cost Estimates

Construction cost constitutes only a fraction, though a substantial fraction, of the total project cost. However, it is the part of cost under the control of the construction project manager. The required levels of accuracy of construction cost estimates vary at different stages of project development, ranging from ballpark figures in the early stage to fairly reliable figures for budget control before construction. Since design decisions made at the beginning stage of a project life cycle are more tentative than those made at a later stage, the cost estimates made at the earlier stage are expected to be less accurate. Generally, the accuracy of a cost estimate will reflect the information available at the time of estimation.

Construction cost estimates may be viewed from different perspectives because of different institutional requirements. Despite the many types of cost estimates used at different stages of a project, cost estimates can best be classified into three major categories according to their functions. A construction cost estimate serves one of the three basic functions: design, bid and control. For establishing the financing of a project, either a design estimate or a bid estimate is used.

- Design Estimates: For the owner or its designated design professionals, the types of cost estimates encountered run parallel with the planning and design as follows:

- Screening estimates (or order of magnitude estimates)

- Preliminary estimates (or conceptual estimates)

- Detailed estimates (or definitive estimates)

- Engineer’s estimates based on plans and specifications

For each of these different estimates, the amount of design information available typically increases.

- Bid Estimates: For the contractor, a bid estimate submitted to the owner either for competitive bidding or negotiation consists of direct construction cost including field supervision, plus a markup to cover general overhead and profits. The direct cost of construction for bid estimates is usually derived from a combination of the following approaches.

- Subcontractor quotations

- Quantity takeoffs

- Construction procedures.

- Control Estimates: For monitoring the project during construction, a control estimate is derived from available information to establish:

- Budget estimate for financing

- Budgeted cost after contracting but before construction

- Estimated cost to completion during the progress of construction.

Design Estimates

In the planning and design stages of a project, various design estimates reflect the progress of the design. At the very early stage, the screening estimate or order of magnitude estimate is usually made before the facility is designed, and must therefore rely on the cost data of similar facilities built in the past. A preliminary estimate or conceptual estimate is based on the conceptual design of the facility at the state when the basic technologies for the design are known. The detailed estimate or definitive estimate is made when the scope of work is clearly defined and the detailed design is in progress so that the essential features of the facility are identifiable. The engineer’s estimate is based on the completed plans and specifications when they are ready for the owner to solicit bids from construction contractors. In preparing these estimates, the design professional will include expected amounts for contractors’ overhead and profits.

The costs associated with a facility may be decomposed into a hierarchy of levels that are appropriate for cost estimation. The level of detail in decomposing the facility into tasks depends on the type of cost estimate to be prepared. For conceptual estimates, for example, the level of detail in defining tasks is quite coarse; for detailed estimates, the level of detail can be quite fine.

For example, consider the cost estimates for a proposed bridge across a river. A screening estimate is made for each of the potential alternatives, such as a tied arch bridge or a cantilever truss bridge. As the bridge type is selected, e.g. the technology is chosen to be a tied arch bridge instead of some new bridge form, a preliminary estimate is made based on the layout of the selected bridge form based on the preliminary or conceptual design. When the detailed design has progressed to a point when the essential details are known, a detailed estimate is made based on the well-defined scope of the project. When the detailed plans and specifications are completed, an engineer’s estimate can be made based on items and quantities of work.

Fundamentally, all conceptual price estimates are based on some system of gross unit costs obtained from previous construction work. These unit costs are extrapolated forward in time to reflect current market conditions, project location, and the particular character of the job presently under consideration.

Some methods commonly used to prepare preliminary estimates include:

- Cost Per Function: This analysis is based on expenditure per unit of use, such as cost per patient, student, seat, or car space. These parameters are generally used as a method of quickly defining facility costs at the inception of a project when only raw marketing information is known, such as the number of patients a planned hospital will hold.

- Index Number Estimate: This method involves estimating the price of a proposed project by updating the construction cost of a similar existing facility. It is done by multiplying the original construction cost of the existing project by a national price index that has been adjusted to local conditions, such as weather, labor expense, materials costs, transportation, and site location. Many forms of price indexes are available in various trade publications.

- Unit Area Cost: This method of estimating facility costs is an approximate cost obtained by using an estimated price for each unit of gross floor area. The method is used frequently in building and residential home construction. It provides an accurate approximation of costs for buildings that are standardized or have a large sampling of historical cost information from similar buildings.

- Unit Volume Cost: This estimate is based on approximate expenditure for each unit of the total volume enclosed. This estimating method works well in defining the costs of warehouses and industrial facilities. It can also be valuable in developing specialty estimates for heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

- Parameter Cost Estimate: This estimate involves unit costs, called parameter costs, for each of several different building components or systems. The prices of site work, foundations, floors, exterior walls, interior walls, structure, roof, doors, glazing, plumbing and other items are determined separately by the use of estimated parameter costs. These unit costs can be based on dimensions of quantities of the components themselves, or on the common measure of building square footage.

- Partial Takeoff Estimate: This analysis uses quantities of major work items taken from partially completed design documents. These are priced using estimated unit prices for each work item taken off. During the design stage, these are considered to provide the most accurate preliminary costs. Generally, this estimate cannot be made until well into the design process.

- Bid Estimates: The final cost estimate of a project is prepared when finalized working drawings and specifications are available. This detailed estimate of construction expense is based on a complete and detailed survey of work quantities required to accomplish the work. The process involves the identification, compilation, and analysis of the many items of cost that will enter into the construction process. Such estimating, which is done before the work is performed, requires a careful and detailed study of the design documents, together with an intimate knowledge of the prices, availability, and characteristics of materials, construction equipment, and labor. A thorough knowledge of construction field operations required to build the specific type of project under consideration is also essential.

The contractor’s bid estimates often reflect the desire of the contractor to secure the job as well as the estimating tools at its disposal. Some contractors have well-established cost estimating procedures while others do not. Since only the lowest bidder will be the winner of the contract in most bidding contests, any effort devoted to cost estimating is a loss to the contractor who is not a successful bidder. Consequently, the contractor may put in the least amount of possible effort for making a cost estimate if it believes that its chance of success is not high.

If a general contractor intends to use subcontractors in the construction of a facility, it may solicit price quotations for various tasks to be subcontracted to specialty subcontractors. Thus, the general subcontractor will shift the burden of cost estimating to subcontractors. Suppose all or part of the construction is to be undertaken by the general contractor. In that case, a bid estimate may be prepared based on the quantity takeoffs from the plans provided by the owner or based on the construction procedures devised by the contractor for implementing the project.

For example, the cost of a footing of a certain type and size may be found in commercial publications on cost data which can be used to facilitate cost estimates from quantity takeoffs. However, the contractor may want to assess the actual construction cost by considering the construction procedures to be used and the associated costs if the project is deemed to be different from typical designs. Hence, items such as labor, material and equipment needed to perform various tasks may be used as parameters for the cost estimates.

Control Estimates

Both the owner and the contractor must adopt some baseline for cost control during the construction. For the owner, a budget estimate must be adopted early enough to plan long-term financing of the facility. Consequently, the detailed estimate is often used as the budget estimate since it is sufficiently definitive to reflect the project scope and is available long before the engineer’s estimate. As the work progresses, the budgeted cost must be revised periodically to reflect the estimated cost to completion. A revised estimated cost is necessary either because of change orders initiated by the owner or due to unexpected cost overruns or savings.

For the contractor, the bid estimate is usually regarded as the budget estimate, which will be used for control purposes as well as for planning construction financing. The budgeted cost should also be updated periodically to reflect the estimated cost to completion as well as to ensure adequate cash flows for the completion of the project.

Test your Knowledge!

Which of the following best describes the significance of accurate cost estimating in construction projects?

Sources of Estimating Data

To develop an estimate of the cost to construct a facility, it is important to identify data sources that will be used for the estimate. There are many different potential data sources. They can be divided into the following categories:

- Actual Cost Data

Depending upon the level of detail, and time available, you can obtain actual price quotes and actual cost information for some, or many, of the elements that will be included in the estimate. For example, if you are going to subcontract portions of the project, e.g., the concrete or steel trade, you can request quotes from one or multiple potential trade contractors. You can also contact suppliers to get firm quotes on the cost of specific materials and equipment. Finally, you can get actual wage rates for workers on the project, although you will still need to develop estimates for how many hours the work activities will take. If you can get firm quotes from subcontractors and suppliers, with a time period to accept and contract with them for the supplies and equipment, then you have a high degree of confidence in the actual costs for the portions of the project estimate.

- Historical Cost Data – Company Data

If you can not obtain actual cost quotations, or for work activities that a contractor will directly perform, they can leverage historical data from their own projects. For example, suppose you are a concrete contractor and you are developing an estimate for the concrete work on a future office building. In that case, you can review the actual costs and production rates from previous projects that your company has performed. When doing so, it is critical for the estimating team to fully understand the context of the previous projects, along with how the project team tracked their costs. If a company maintains good records of previous project costs and production rates, then it can relatively easily develop estimates for similar future projects that are quite accurate.

- Historical Cost Data – National / Regional Averages

For organizations that do not have their own data available, some organizations collect cost data and then report this data through online databases or cost-estimating guides/books. These organizations are typically collecting data from many projects that are performed in many locations, and then averaging and modifying this data to represent average national construction costs. The data will also be compiled at different levels of detail, e.g., individual work activities, building systems, and overall building-level costs. It is always important to keep in mind that the data in these cost guides/databases are averaged data, and individual site conditions, project complexity, and other factors may significantly impact potential costs. Therefore, these are the easiest sources of data to find but are not as reliable as accurate, well-organized company data sources.

The most broadly used data source for historical data is the information from R.S. Means. R.S. Means has a series of books that outline costs for a variety of project types and levels of detail.

For example, they have guides for Unit Price estimating, Square Foot estimating, and Assemblies Estimating. They also have guides for various specific trades, e.g., concrete, steel, masonry, mechanical and electrical. They have some guides for specific purposes, e.g., renovations, facility management, and green buildings. Finally, they also have guides with cost differentials based on the labor used, e.g., the Open Shop cost guide for non-union labor. It is important to note that all guides unless specifically noted as ‘Open Shop’ are priced with wage rates for a union or prevailing wage workforce.

Impact of Time on Cost

As time progresses, it is typical for costs to escalate, at least in most economic conditions. Broadly, this is known as inflation, and we typically measure this cost escalation by pricing a series of goods over time and seeing how the price changes from one time period to another. The most typical measure in the US for inflation is the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is calculated from a typical basket of goods that an average person may buy, e.g., food, gas, etc.

When we estimate projected building costs, there are similar cost escalations that occur. Still, these escalations are more targeted toward the cost escalation of building materials and the labor cost for construction. Therefore, it is more accurate to consider cost escalation by calculating the escalation of a construction-related ‘basket of goods’. RS Means has developed several specific cost index values, similar to CPI but focused on construction. These include the Building Cost Index (BCI) which contains typical products and labor for building construction; the Construction Cost Index (CCI) which is much broader to cover roads, bridges, and infrastructure; and the Material Cost Index for building materials.

When we perform cost estimates for building projects, we will focus on using the BCI value since it is more targeted to buildings. If you compare BCI values for two periods in time, then you can transition relative economic values between these times with a simple calculation of ratios. The BCI, CCI, and MCI are all reported in the Engineering News-Record publication, which is published each week. Monthly and annual averages are also available on the ENR website.

When using the RS Means data, it is valuable to know that the data within a cost guide is updated to be consistent with the index values for January of the year on the cover. For example, if you have a 2023 RS Means Building Construction Cost Guide, all cost data will be statistically modified to be consistent with the January 2023 BCI.

If you are a private organization that maintains your own cost data, you will also want to modify the data based on the time of construction. Individual companies may maintain their information to modify these costs. For example, Turner Construction maintains and even publishes, its cost index over time.

The escalation of costs over time can vary significantly, but on average, construction costs have historically risen approximately 3% per year. When we estimate future construction costs, we need to consider the projected future cost increases. Throughout this class, unless otherwise noted, a projected escalation of 3% per year can be used for future construction cost escalation. Companies will be reviewing their recent experience and projected future market conditions to establish the escalation values that they project when developing their cost estimates. This can have a significant impact on their final economic success on certain types of projects, e.g., lump-sum contracts, especially for projects that span several years.

Modify Index Values for Location

Construction costs vary by geographic location to due differences in material, equipment, and labor costs. These variations can be significant. These cost variations can be caused by many factors, including local costs of resources, site conditions (e.g., urban construction tends to cost more than rural), availability of contractors, taxes, and overall region or country economics. In the 2021 International Construction Market Survey by Turner & Townsend, they found Tokyo, Hong Kong, and San Francisco to be the 3 most expensive cities in the world to build. It is interesting to see that 4 of the top 10 most expensive locations are major cities within the United States.

In the RS Means data, they develop all their data into a national average for publishing, and then they publish Location Factors for different cities. For example, a location factor for Dickinson, North Dakota can be identified in the Location Factor table which is included in the back of each of the Gordian Guides with RS Means data. The national average is 1.0, and the commercial construction location factor for Dickinson is 0.85. Therefore, if a building is estimated from the guide to cost $100 million, then the estimated cost in Dickinson would be $85 million. Gordian publishes both residential and commercial location factors in some tables. Note that the residential location factors are targeted toward single-family detached residential, not residential apartment buildings which would be considered commercial construction. Some guides also publish specific City Indexes which are more specific for altering the cost for both time and location within a given city. RS Means publishes city indexes for 20 large cities in the US.

There are also international indexes that allow estimates to be transitioned from one country to another, although this is certainly not as accurate for many purposes.

Understanding the Audience

One important aspect of cost estimating is to always understand and project your audience for the estimate. If you are developing an estimate for an owner, early in the project, you will want to make sure that the owner is aware of the potential variation, and that you clearly define what is included in the estimate, and which items are not included. For example, if you perform a Rough Order of Magnitude estimate using RS Means, the estimate will include construction costs, but it will not include the design fees, land costs, or extensive site work. These inclusions and exclusions vary by the type of estimate performed.

Stop and Reflect 4.1: Schedule or Budget?

Overview

Some will say that there is a triangle balanced between schedule, budget, and scope/quality. You can increase quality and maintain your schedule, but it will likely result in an increased budget. You can cut the budget and shorten the time frame, but you will be reducing the quality of the project as well. If quality were to remain the same, a change to schedule would affect budget and vice versa.

Prompt

Reflect on the critical aspects of managing a project: Do you believe adhering to the scheduled timeline or staying within the budget is more crucial? Support your viewpoint with examples or reasoning. Your explanation will help illuminate your thought process and decision-making priorities in project management. What leads you to prioritize one over the other, and how do you balance the two in the face of project constraints? Your insights will contribute to understanding the strategic choices that shape successful project outcomes.

In your reflection include the following:

- Why did you choose either the schedule or the budget?

- Use the resources provided to back up your choice.

Evaluation

The overall goal of this discussion is to get you thinking about the priorities of a project from both time and money and to be able to defend your decisions regarding potential changes to them.

You will be evaluated based on the following criteria:

- Answered the question, providing clear reasoning for your choice.

- Provide at least one resource to back up your choice.

Lesson 2: Construction Project Delivery Methods

Project owners use many different approaches to procure the services needed to design and build a facility. No matter how simple or complex, the owner and project team must decide how to acquire the services to deliver their facility. These decisions are developed into an overall project delivery approach. Part of this is what we call the construction delivery method and affects project organizational structure as well as the type of contracting method that will be used during procurement.

The Four most common methods are:

- Design-Bid-Build

- Design-Build

- Construction Manager at Risk (CMAR)

- Integrated Project Delivery (IPD)

Design-Bid-Build: The Traditional Approach

Design-Bid-Build is the most widely used construction delivery method, characterized by its linear process. The project owner maintains separate contracts with the designer and the contractor, selecting the contractor through a bidding process after the design phase is complete.

Characteristics and Risks:

- Two Separate Contracts: One with the designer and another with the contractor.

- Qualifications-Based Selection with Fixed Price: The contractor is selected based on qualifications and offers a fixed price.

- High Risk of Constructability Problems: This method often faces design issues, leading to a longer time to completion.

Design-Build: A Collaborative Contract

Under the Design-Build method, the project owner signs a single contract with an entity that combines the architect and general contractor, streamlining the process.

Advantages and Owner’s Role:

- Less Owner Involvement: This method requires fewer internal resources from the project owner.

- Risk and Responsibility: The owner faces risks, but the method allows for a reduction in time and fewer disputes within the team.

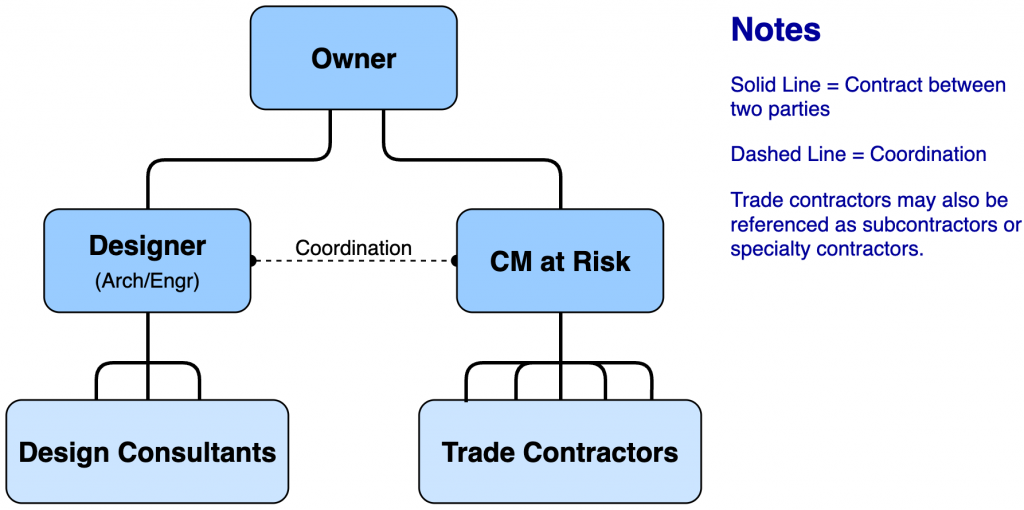

Construction Manager at Risk (CMAR): The Hybrid Method

CMAR involves the project owner hiring the contractor at the same time as the design team, with an agency contract establishing a fixed price for pre-construction and a guaranteed maximum price for construction.

Benefits of CMAR:

- Reduced Risk: CMAR minimizes the need for redesign and allows for the fast-tracking of completed portions.

- Fixed Price for Pre-Construction: Ensures cost management from the early stages.

Integrated Project Delivery (IPD): Emphasizing Collaboration

IPD is a multi-party agreement that emphasizes shared control, liability, and the most collaborative approach among all stakeholders.

Key Features

- Shared Risk and Reward: Risks are assigned to the appropriate party, focusing on meeting project outcomes and milestones through a cost-plus incentive contract.

- Project Goals Alignment: Ensures all parties are aligned with the overall project goals.

As you move forward in your studies and professional endeavors, keep these methods in mind as they will greatly influence the approach and success of your future construction projects.

Project Delivery Methods

Project owners use many different approaches to procure the services needed to design and build a facility. Some facilities are quite easy to build, relatively speaking, such as a simple single-family detached house. This type of building may allow an owner to simply hire one entity to both design and build their building. Others are very complex facilities, such as a large industrial facility or a complex hospital or lab. These can engage many organizations. But no matter how complex, the owner, and other project participants, have many decisions to make related to developing their strategy to acquire the services that they need to deliver their facility. These decisions can be developed into an overall Project Delivery approach.

It is important to note that before developing the overall project delivery strategy, an owner must clearly define the scope boundaries of a project. For example, sometimes an owner will seek to build multiple buildings on a large parcel. If so, then the owner will need to decide whether to make each building a project or group the buildings into a single project. For office buildings, the owner may need to decide whether to have the core and shell be one project, and the tenant fit-out is a second project or multiple additional projects. These decisions define the extent of the project scope.

Primary Elements of a Project Delivery Strategy

Several core project delivery decisions that will influence the project include:

- Defining the organizational structure;

- Defining the contracting method(s) (payment method(s)); and

- Defining the award method(s).

- These decisions are certainly related to each other, and we will explore some typical combinations.

Project Organizational Structure

The project organizational structure focuses on the approach that is used to organize the team members. This structure can have a significant impact on team responsibilities, roles, level of risk, and interactions. The organizational structure is defined by the contracts that are put into place by the team members. For example, in a Design-Bid-Build approach, the Owner will sign separate contracts (or agreements) with a Designer and a General Contractor. Each contract will clearly define the scope of services to be performed by each entity.

The 7 organizational structures that may be used include:

- Design-Bid-Build with a GC (also known as Traditional Delivery)

- Design-Bid-Build with multiple prime contractors

- CM Agent with GC

- CM Agent with multiple prime contractors

- CM at Risk

- Design-Build

- Integrated Project Delivery (IPD)

Design – Bid – Build with a General Contractor

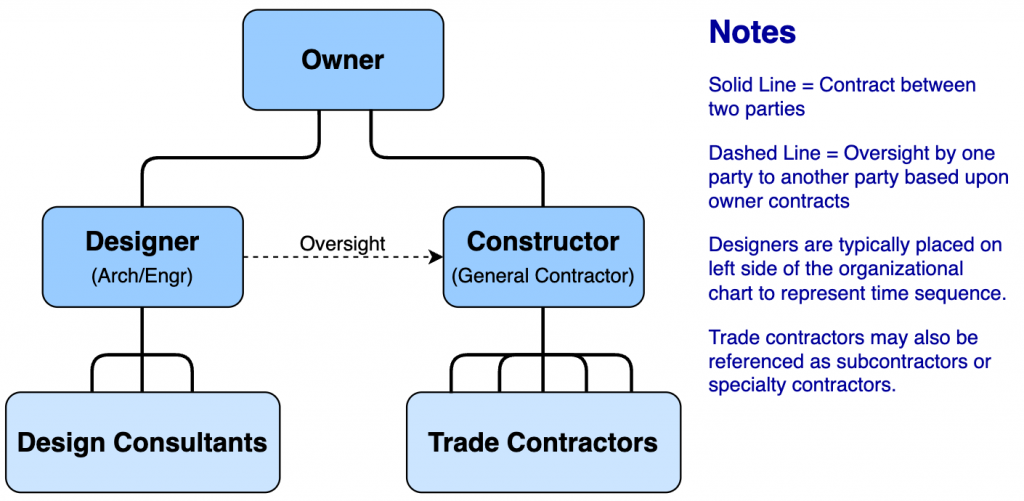

Often referred to as ‘traditional’ delivery, the design-bid-build with a General Contractor (DBB with GC) remains quite commonplace. In this approach, an owner will initially hire a design firm (typically an Architect for a commercial building project). The designer will fully develop the design documents, through the completion of the Construction

Documents phase (100% complete), and then the Owner will release the documents for the bid for a single organization (the General Contractor) to perform all scopes of work in the project. The potential general contractors will provide a bid to the owner. Typically, the owner will then select the lowest bidder, although they may use a different award method (see later in the chapter). The owner will then enter into a contract with the Constructor (a General Contractor) to construct the building. A diagram showing the project organizational structure for DBB with GC is shown in Figure 4.2.

This figure shows solid lines for contracts. It includes a dashed line between the design and the contractor to illustrate the influence that the Designer has on the Constructor based on the owner’s contracts. For example, the architect will typically review the constructor’s payment request prior to payment. The architect will also typically review the completed work of the constructor to ensure that it meets the defined quality in the contract. If it does not, the architect will develop a deficiency list (frequently referred to as a punchiest) that will need to be addressed before acceptance of the GC’s work by the owner. It is critical to understand that the architect will have influence over the GC, but the Architect will not hold any contract with the GC. This becomes very important if there is a claim on the project since claims will typically only follow contract relationships.

The DBB with General Contractor (GC) approach is a common method for public procurement. It has been viewed by many in the public sector as an approach to provide fair competition for entities who competitively bid on the project and a clear selection criterion (low bid) when delivered with a competitive bid award method. There are also many other entities that use this approach.

Some benefits of DBB with GC are:

- The GC knows the full scope of the project, as defined in the construction documents, before providing a bid for the work;

- The Owner can select a design firm independent of their ability to construct a project;

- The Owner has clear criteria to select the constructor (low bid) since the Design-Bid-Build approach almost always aligns with a low bid selection process. The bidders may need to prequalify to bid on the project.

- The Owner may get a lower price if the scope is well-defined and there is strong competition for bidding on the project.

However, there are some significant challenges with this approach. These include:

There is no opportunity for a contractor to provide input into the design process, which can limit the potential for gaining early cost estimates, constructibility feedback, and feedback to improve opportunities for modularization or prefabrication.

- It is not always clear that the low bidder will yield the lowest final cost since there tend to be higher rates of change orders given this approach.

- This is a slow delivery approach since the design must be 100% complete before putting the documents out to bid.

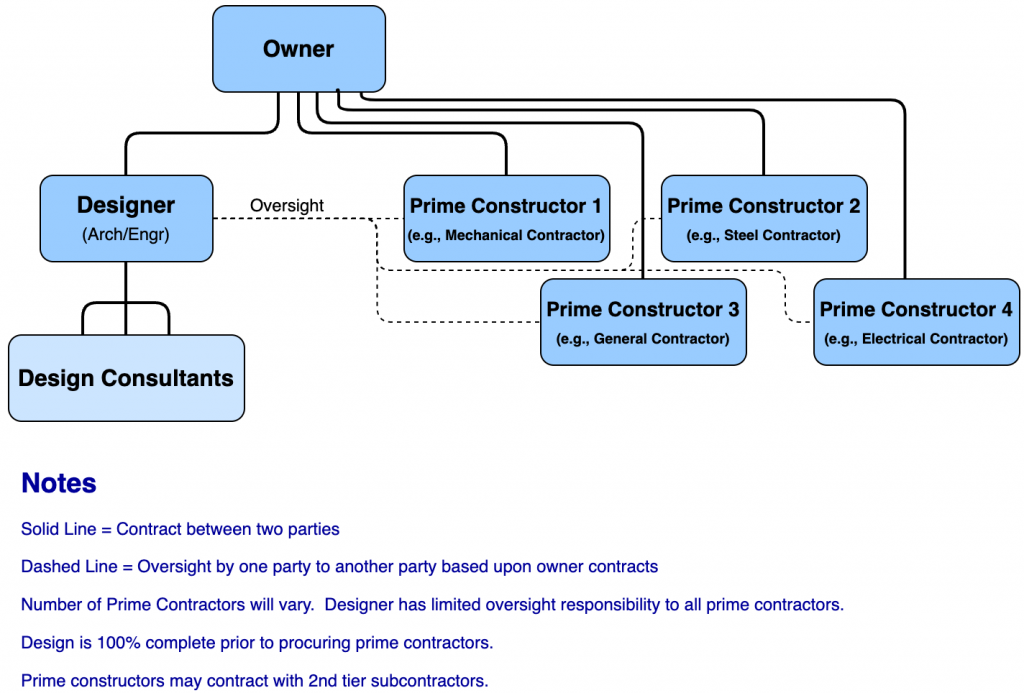

Design – Bid – Build with Multiple Prime Constructors

One variation of Design-Bid-Build is for the owner to separate the scope of work into multiple trade or scope packages, and then independently bid each package. This yields a similar structure to DBB with GC, but instead of a single GC, there are multiple trade contractors (see Figure 4.3). This approach carries many of the same advantages and disadvantages as the DBB with GC. One envisioned additional advantage of this approach is that the Owner will not pay overhead costs for a GC to manage the other prime trade contractors. But, one additional disadvantage is that the Owner will now take on additional responsibility in the management of the various prime contracts. This will require additional coordination and administrative effort for the Owner. For less experienced owners, this additional burden can be quite challenging.

Note that this delivery approach is sometimes required by public procurement regulations for a small number of public owners. One public owner that sometimes requires DBB with Multiple Prime is the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. For state-funded projects in Pennsylvania, there is a minimum requirement per the Separations Act, 71 P.S. §1618 that the owner use a multiple-prime delivery system with each prime construction contract being competitively bid.

The minimum number of prime contractors includes:

- general construction

- electrical

- plumbing

- heating and air conditioning

For this reason, there are several schools and other public projects funded by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania that must be delivered with this approach.

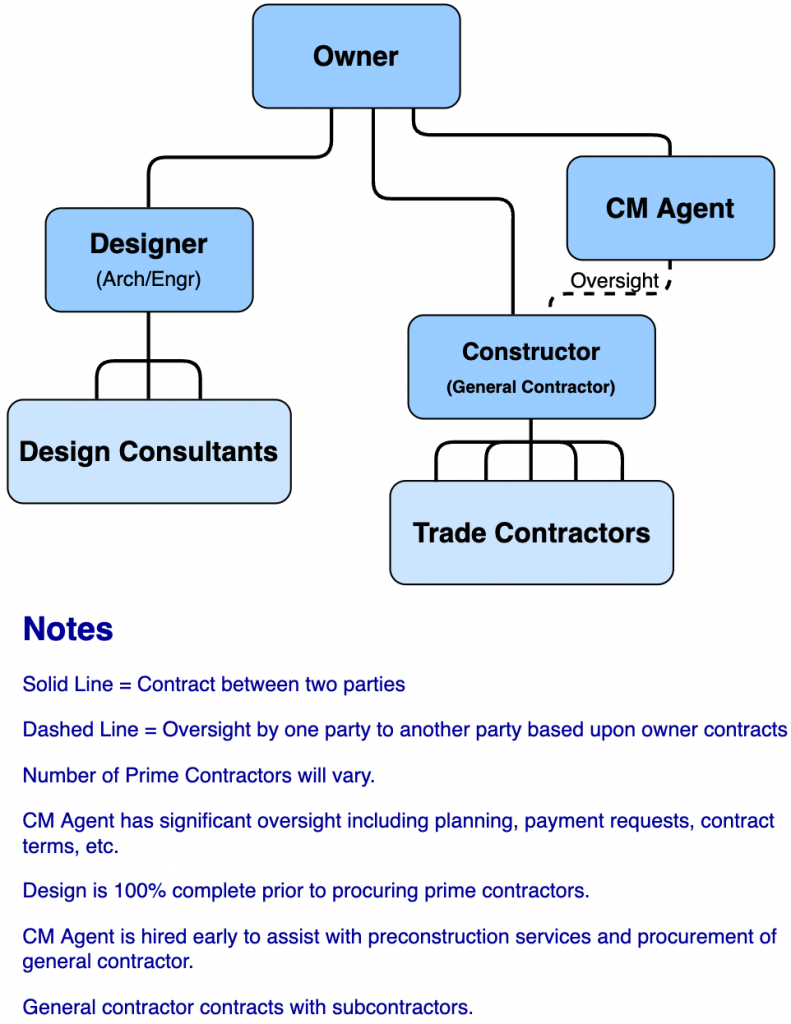

Construction Management Agent with General Contractor

The Design-Bid-Build delivery approach requires significant interactions by the owner of the project during the delivery process. To assist with the tasks that need to be completed by an owner, and provide significant expertise to deliver a project effectively, some owners will deliver

a project with a Construction Management Agency. This CM Agent will be a paid entity that helps an owner perform their required activities in the delivery process, including the oversight of procurement of entities throughout the project, administering of contracts, planning and coordinating construction activities, approving payment requisitions, overseeing overall project safety and quality, providing constructability input into the design, along with many other tasks. This CM Agent arrangement is particularly valuable for complex projects, or for projects that have an owner who may not have the resources or expertise to manage the project effectively.

The CM Agent will review the operations of the General Contractor (GC), and report important information to the Owner. It is important to note that the CM Agent has no direct contract with the General Contractor. This limits the liability and responsibility between the General Contractor and CM Agent. If the GC were to file a claim, they would need to do so with the Owner, since claims will follow the contractual relationships. In some instances, the CM Agent with a GC arrangement may pose a scenario where one market competitor will be overseeing another market competitor, which can be a challenging dynamic.

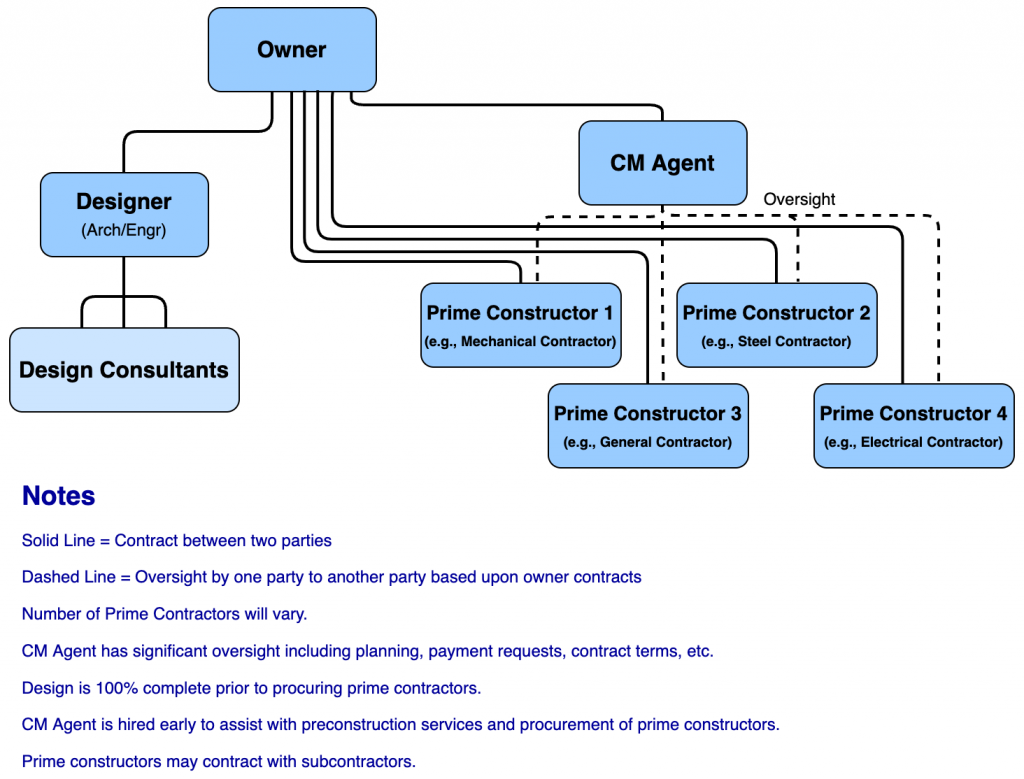

Construction Management Agent with Multiple Prime Contractors

This approach places a CM Agent into the organizational structure of the DBB with Multiple Prime Contractors. This can be quite helpful in assisting with some of the challenges inherent in the DBB with Multiple Primes. For example, the CM Agent can be hired early in the process, and then provide construction input into the design, and monitor cost estimates throughout the design phases. The CM Agent can also organize and prepare the different bid documents to hire multiple trade contractors. Finally, the CM Agent can supplement the owner’s resources to coordinate the contractors and administer their contracts. This is a common method to use when there are procurement regulations that require DBB with Multiple Prime Contractors.

Construction Management at Risk

Construction Management at Risk is an approach where the owner will hire a designer to develop the facility design, and sometimes, usually early in the design process, they will hire a construction management company to perform both construction services during design along managing the overall construction of the facility. The services that they will provide during design will include reviewing the design for constructability, developing bid packages for the hiring of trades, identifying and prequalifying trades, and performing cost estimates. A CM at Risk will eventually Guarantee a price for the project. This is frequently performed through a Cost + Fee with a Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP) contract, but it could also be through a lump sum contract (see details later in this chapter). The CM is at risk since they directly hold all contracts with the trade contractors, in contrast to the CM Agency where the Owner holds the contracts with the trade contractors. A CM at Risk is a good delivery method to allow an owner to hire a preferred designer, still have some checks and balances in the system, yet also gain benefits from early constructor involvement. This approach allows for collaboration between the design and CM, although this collaboration is not always as close as some of the more integrated approaches of Design-Build or IPD. The CM is at risk since they directly hold all contracts with the trade contractors. This delivery method may also be referenced by different names. In particular, within the highway construction sector, this delivery method is known as Construction Management/General Constructor (or CMGC).

Design-Build

Design-Build (DB) is focused on having a single entity perform both the design and construction of a project. Within the Design-Build approach, an Owner will hire a single entity after developing a program for the project. The program will outline the requirements for the project, e.g., space requirements and other designed outcomes. The design-build entity will then perform the design of the facility and be responsible for construction.

A core and unique aspect of design-build is the single contract between the Owner and the Design-Build entity. The design-build entity will be a legal entity but could take many different forms. For example, it could be an integrated design-build company, or a single-purpose joint venture developed between a design firm and a construction firm to pursue a project. In many instances, the design-build entity is a construction company, which then subcontracts the design tasks to a designer. In some cases, the design-build entity is a designer, who subcontracts construction to a construction company, although this is rare.

This single entity approach for both design and construction allows for many potential benefits. It allows for a very tight integration of construction means and methods with the design of the facility. It also allows the team to develop accurate cost estimates throughout the early design phases, and identify approaches to save costs and provide added value within the construction process.

While there are many benefits to the integration that can occur in Design-Build, there are also some potentially negative aspects. A primary concern that may be expressed within design-build is that the owner may not have an independent advocate within the checks and balances of having both a design and construction contract. In a more traditional approach, the design firm frequently has some oversight role of the contractor, and the contractor has an opportunity to share their opinions regarding the designer with the owner. In a design-build project, the owner does not have a second opinion in the same manner, and therefore, may not

receive the same feedback. The owner may also have concerns that the design-build firm is trying to maximize its success to the detriment of the project. While these are valid concerns that must be appropriately managed through project control systems and hiring a high-quality team, many owners find design-build to be a very effective method to deliver a project.

Integrated Project Delivery (IPD)

Integrate Project Delivery (IPD) is a newer contracting format where the entire team is engaged in the successful delivery of the project, including the owner, designer(s), and contractor(s) through a very integrated, shared risk/reward approach. Projects delivered using the Integrated Project Delivery organizational structure have core members enter into an Integrated Form of Agreement (IFoA). This IFoA is a single contract for the project that is signed by all core team members, including the owner. This is a very unique structure that is unlike other delivery methods. Typically, all core members will share the risks of designing and delivering the project, along with the potential financial rewards if the project is delivered on or below the target budget while meeting the other project goals.

There are typically many unique management aspects associated with IPD projects. For example, the integrated team will frequently form a cluster group at the beginning of the project to manage particular scopes of work or focused issues. They will frequently set up a ‘big room’ to collocate the team to a common location to better integrate the design and construction team members. During design, the team will frequently use target value design approaches to ensure that they are designing the project to budget. They will also frequently leverage lean construction methods, including pull planning and the Last Planner System, to manage production. These different systems will be discussed in more detail in a later chapter. A good discussion of the IPD delivery approach is included in Integrated Project Delivery: A Guide.

Test your Knowledge!

Which project delivery method involves the project owner hiring a contractor at the same time as the design team, and establishing a fixed price for pre-construction services?

Contracting Method

There are many items covered within a contract. One of the most significant items in the contract in relation to the delivery approach is the payment terms, which define how payments are made from one party to another. Common payment terms include lump sum, cost plus a fee, cost plus a fee with a Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP), or unit cost.

Lump-Sum (or Stipulated Sum)

In a lump sum payment approach, the owner will pay a fixed amount to the contractor for the work performed. This amount is paid on a periodic basis, typically each month. For the prime contractor(s), a Lump Sum arrangement typically corresponds with a traditional, design-bid-build delivery approach, although it can be used with other organizational structures. Within a Lump Sum contract, the contractor will either make a profit, if they can construct the building for less than the lump sum value, or they will lose money if they can not construct the building for the value. This transfers a significant amount of the risk for financial performance to the constructor. If the contract scope is changed or there are errors in the construction documents that increase the cost of construction, the constructor can file for a change order to increase the lump sum value. A lump sum payment arrangement may also be referenced as a stipulated sum arrangement. It is also important to note that many owner-designer contracts have a stipulated sum (or lump sum) amount. This value may be estimated as a percentage of the total project costs, but the value is frequently incorporated into the contract as a stipulated sum. The design firm may also have additional compensation amounts, e.g., reimbursement for travel to the site or meetings.

Cost Plus a Fee

The Cost Plus a Fee approach leaves the final contract value open. It is a contractual arrangement where the owner (or a separate prime contractor) pays for all costs of performing the work, including labor, materials, equipment, and potentially other costs, plus an agreed-to fee. The fee may be a lump sum fee or it may be a percentage of the cost of work. A cost-plus-a-fee arrangement is typical for projects where the full scope is not well defined, and the owner wishes to start the work. This contracting method carries a significantly lower risk to the contractor. The contractor will need to account for all of their costs, and share these details with the owner. This approach is frequently referred to as Open Book since the contractor will share their accounting with the owner, and the owner typically has the right to perform a full audit of the books.

Cost + Fee with Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP)

When we talk about “Cost Plus Fee with Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP)” contracts, we’re looking at a smart way to keep construction project costs in check. Think of it like setting a budget limit for a group project. Essentially, the project owner agrees to cover all the project expenses plus a specific fee, but only up to a certain point — that’s the GMP or the budget ceiling. If the team (in this case, the contractor) spends more than this ceiling, they won’t get extra money beyond the GMP. But, if they spend less and save money, there’s a reward.

So what happens to these savings? Typically, the savings are split between the project owner and the contractor. For example, they might divide it 50-50 or maybe 75-25 in favor of one side. In some cases, the owner could keep all the savings. Let’s say the contractor manages to save $10,000 under the GMP. If the split is 50-50, both the owner and the contractor get $5,000 each. If it’s 75-25, the owner could take $7,500, leaving $2,500 for the contractor.

Contractors keep an open book, regularly showing detailed bills for their costs. This “Open Book” approach is like sharing your project work with the team so everyone can see and agree on the expenses. It’s about ensuring that the project’s budget is transparent and well-managed.

Unit Price

For some scopes of work, although not typically an entire project, an owner or contractor will pay a supplier or subcontractor a unit price amount for a scope of work. For example, the contractor may pay for concrete by a cubic yard of a specific mix design, or an excavation subcontractor may be paid by the cubic yard of excavated material. A benefit of the unit price payment method is that you can set up a project with a clear cost per unit, while not necessarily knowing the full scope of the work. A downside for the contracting entity is that there is no guaranteed final cost since it is dependent on the quantity, and there must be a quality method to document the actual quantity performed.

Award Method

When one party would like to hire another party to perform a service or provide a product, the party must decide how they will select the other party. There are many different approaches to selecting the method that they will use to award the contract. For design and construction contracts, these methods can be broadly categorized into

- Competitive Bid,

- Prequalified Competitive Bid,

- Best Value Selection

- Negotiated Selection.

Competitive Bid

One traditional method to select a contractor is to select the lowest cost contractor in a competitively bid arrangement. In this approach, all contractors will submit a bid, and the Owner, or selecting entity, will review the bids and select the lowest cost qualified bidder. This approach is very commonly used for public projects, along with many private projects.

Prequalified Competitive Bid

One challenge of an open competitive bid is that the owner may select a contractor who technically fits the qualifications, but that the owner does not feel has more advanced qualifications. In some instances, an owner will proceed with a 2 step process. They will first prequalify a subset of the potential bidders, through the review of a qualification submission for each potential bidder. Then, they will ask each of the prequalified bidders to submit a bid for the cost of the project, and they will select the lowest cost bidder from the prequalified contractors.

Best Value Selection

Another approach to selecting a contractor is to develop a best-value selection process. In this approach, the owner will identify the criteria that they value, and develop an approach to weigh each of the criteria. These criteria may include the quality of the team, experience on a similar project, plan for approaching the project, and other criteria. They will also include cost as a factor, but not as the only selection factor. Once these criteria are identified, then the owner will review the submissions from potential contractors and rate each of the criteria. The final item to be reviewed and weighted will be the cost. The selection will occur based upon the contractor who rates the highest in the combined weighted equation. This approach can yield the selection of a contractor who aligns more closely with the values of the project.

Negotiated Selection

A final approach to selecting a contractor is to identify an entity (or entities) that you would like to hire, and then directly negotiate a mutually acceptable agreement with the entity. This has the benefit of being able to select the entity directly, but this may not be allowed in many public organizations due to a lack of competitive selection. There are exceptions in public procurement laws, but this is typically not allowed.

Selecting a Project Delivery Method

Several guides and tools have been developed to assist owners in the selection of delivery methods. One of the earliest tools developed was the Project Delivery Selection System (PDSS) by Vesay (1991). This simple decision matrix aimed to point an owner to potential delivery approaches that may be most appropriate for their project given a series of project characteristics. In particular, Vesay developed a decision tree using 6 project characteristics which include:

- Scope Definition: Is the scope of the project clearly defined at the time of procurement? (Well Defined/Poorly Defined)

- Time Criticality: Is time critical to achieving project success? (Yes/No)

- Owner Experience Level: Is the owner experienced with managing the delivery of projects? (Yes/No)

- Team (or potential team) Experience Level: Is the team, or the pool of potential team members, experienced with the delivery of similar projects? (Experienced/Inexperienced)

- Quality Level: Is the level of desired quality equivalent to industry standards or above industry standards? (Industry Standard (i.s.) or Above Industry Standards (a.s.))

- Cost Criticality: Is the first cost of the facility critical to success? (Yes/No)

From the answer to these six questions, the PDSS recommends the consideration of one or more potential delivery methods and payment methods.

**Note: It may point to one suggested method, multiple suggested methods, or suggest that a characteristic be revised prior to proceeding, e.g., more clearly develop the scope prior to proceeding with the project. These decision trees are simply meant to guide an owner. Specific project characteristics may limit the potential selection of methods (e.g., a procurement law or restriction). Characteristics may also guide an owner to one method over another, e.g., previous history with a successful team. **

Engaging with Industry Experts 4.1

Overview

As part of this module, we’ll be hearing insights from a panel of CM practitioners and owners facilitated by CMAA’s New England Charter. They will discuss how their organizations approach the various project delivery methods and will weigh the pros and cons of each. The Moderator Maureen McDonough, Deputy Chief of Contract Services at the MBTA is joined by David Shrestinian – Director of Program Management, City Point Partners, Patricia Filippone – VP, Business Development & Client Relations, Northeast, Suffolk Construction, Luciana Burdi – Director, Capital Programs & Environmental Affairs, MassPort, Catherine Walsh – Associate VP, Facilities Division, Northeastern University.

Reflection

Once you’ve watched the videos, take a moment to reflect on the new information and perspectives shared. To guide your reflection, consider the following questions:

- Learning Takeaways: What is one new piece of information you learned from the panelists’ insights? How does it add to your understanding of the construction industry?

- Connection to Class Topics: Did the videos help clarify any of the topics we’re covering in class? Describe any connections or insights you’ve made.

- Curiosity and Questions: Were there any questions you wished to ask the panel while watching the videos? If so, were these questions addressed in the content?

- Looking Forward: Based on what you’ve learned, what is one question you would like to explore further?

Evaluation Criteria

Your responses will be evaluated based on the completeness of your answers and the depth of your reflections. Aim to provide thoughtful and detailed responses, with each answer comprising at least one well-developed paragraph. Your complete reflection should not exceed two pages.

This exercise is not only about what you’ve learned from the videos but also about how you integrate this new knowledge with your curiosity about the construction industry.

Lesson 3: Procurement and Purchasing Management

The beginning of the Executing phase is where we begin the bulk of the acquisition of vendors to help us make our project a reality. This includes procuring vendors, following a bidding process, and executing contracts with the chosen vendors. This is called the procurement process.

Introduction to Contracting

Contracts serve as the backbone of project management, providing a legally binding agreement that outlines the obligations and rights of all parties involved. They are essential for defining the scope of work, managing risks, and ensuring compliance with regulatory standards. Through contracts, opportunities for innovation and value addition emerge, offering a clear framework for successful project execution.

The Essence of Contracts

At their core, contracts are about mutual agreement and understanding.

They require:

- Mutual Agreement: All parties have a consensus on the contract’s terms.

- Consideration: Something of value is promised in exchange.

- Competent Parties: All involved parties have the legal capacity to enter into a contract.

- Proper Subject Matter: The contract’s subject is lawful.

- Mutual Right to Remedy: Solutions exist for breach of contract.

Understanding Contract Types

Fixed Price Contracts

In a fixed-price contract, the cost is predetermined, remaining constant regardless of the effort or delivery timelines. This type of contract encourages efficiency but places the cost overrun risk squarely on the contractor.

Fixed Price Contract Variations

- Fixed Total Cost: Offers high predictability but places the risk primarily on the contractor.

- Fixed Unit Cost: Suitable for projects with a high but not complete scope clarity.

- Fixed Price with Incentive Fee: Encourages meeting milestones by offering incentives.

Cost-Reimbursable Contracts

Cost-reimbursable contracts, also known as cost-plus contracts, ensure the contractor is paid for all project costs plus a fee, either fixed or a percentage of the costs. This approach can flexibly accommodate project changes but requires rigorous oversight to manage costs effectively.

Cost Reimbursable Contract Variations

- Cost Reimbursable with Fixed Fee: The contractor’s profit is fixed, regardless of the actual costs.

- Cost Reimbursable with Percentage Fee: The contractor’s fee increases with the project costs.

- Cost Reimbursable with Incentive Fee: Offers incentives for efficiency and cost-saving.

Time and Materials Contracts

Time and materials contracts offer flexibility for projects with uncertain scopes. However, they require careful management to prevent budget overruns, as costs can escalate with increased effort.

Navigating Legal Issues

Contracts are fraught with potential legal challenges, from fraud to disputes. Understanding the legal framework and ensuring compliance is critical for mitigating risks and safeguarding the interests of all parties involved.

Key Legal Concerns

- Contract Fraud: Misrepresentation can lead to severe legal repercussions.

- Contract Disputes: Disagreements over contract terms or execution can result in costly litigation.

Procurement Cycle

Contracts are central to the procurement cycle, influencing project outcomes from start to finish. By understanding the different types of contracts and the legal landscape, you are better equipped to navigate the complexities of construction project management.

Procurement and Purchasing

In this section we delve into the specifics of the procurement process, often synonymous with purchasing, detailing the steps an owner and the main contractor(s) take to secure services and materials for construction projects. Our exploration begins with how an owner selects the main contractor(s) responsible for the construction work, a process influenced by the project’s organizational setup (such as design-bid-build, Construction Manager at Risk, among others) and the criteria used for selection (including lowest cost, best value, or through negotiations).

The Owner’s View

In general, an owner must first identify and define the scope of the work to be procured. If the project is delivered using more integrated approaches, e.g., design-build or CM at Risk, the level of definition will most likely be less specific than if it is a design-bid-build which will have a completed design before procuring the contractor(s). Regardless, the scope must be defined to procure the entity(s) that will perform the construction.

After the scope is defined and documented, the owner will determine the qualifications needed for a contractor to submit a proposal or bid for the project. Then the owner will most likely prequalify the contractors. This may be a very simple process, or it could be extensive, requiring contractors to submit their qualifications for review and evaluation. For example, at Penn State, some projects simply require that the contractors be part of the approved bidder list, which makes it relatively easy for a contractor to be accepted. Others may have what is termed a ‘two-step’ process where the contractors are first selected via a formal prequalification process (through a Request for Qualification (RFQ)), and then a detailed bid/proposal is submitted by the smaller number of prequalified contractors. On larger projects, this selection may aim to reduce the number of bidders to approximately three companies. In summary, a two-step process has an initial Request for Qualifications (RFQ), followed by a Request for Proposal (RFP) or solicitation for bids from the selected qualified bidders.

Test your Knowledge!

In procurement management, what is a primary factor that influences how an owner selects the main contractor(s) for construction work?

The Contractor’s View

For a contractor to submit a bid (or proposal) for a project, they need to develop a detailed construction cost estimate and compile it into their bid value (or budget value if it is a Guaranteed Maximum Price payment method). When a contractor receives the scope of work for the project from the owner, they will need to determine which portions of the work they will self-perform (if selected) and which portions of the work they will subcontract to other companies. For example, if a construction manager is putting together a proposal for a large building, they may decide to subcontract almost 100% of the direct work. If it is a smaller building with a multi-trade general contractor, they may choose to self-perform nearly their entire scope of work.

Once they decide the subcontracted work scope, they will need to develop a series of ‘bid packages’ that define the scope of work for each trade or subset of work that they plan to subcontract. For a building project, these subcontractor scopes of work are frequently defined by the scope of work within a particular section within the project specifications. For example, a construction manager may seek bids for the structural concrete work (in CSI MasterFormat Division 03), so the bid package may be defined by the scope of work for Division 03, possibly with some exclusions and additions. If the project specifications document is well defined, it makes defining a clear scope of work for hiring a trade much easier. If the project design and specifications are not well documented, this task is more difficult since the contractor must be very clear in developing the scope documentation for any subcontracted work.

When developing the bid packages, the contractor must make sure that they have each scope of work covered within their pricing, but they should not include a scope of work in two different bid packages. If a scope of work is not covered at all, it is referenced as a ‘scope bust’, which means that the scope of work is not included in any trade scope and is also not planned to be self-performed. Eventually, someone will need to perform this work and be paid for this work if the contractor wins the contract. Therefore, this will cause them to incur unanticipated costs and could cause them to be over budget. A contractor also does not want to include one scope of work in two different bid packages. This would cause the contractor’s bid value to be artificially high, and if they do win the project, they could inadvertently pay for a specific scope of work twice if they do not realize that there is redundant scope in two subcontracts. This is referred to as ‘scope redundancy’. If they identify this redundancy, they can direct one trade to not perform the work, and request a deductive change order to the subcontract. When this occurs, it can be difficult for the prime contractor to get 100% of the value back from the subcontractor in the negotiations for the deductive change order value.

After defining the scopes of subcontracted work into documented bid packages, the prime contractor will solicit bids from potential specialty trades (sometimes referred to as subcontractors). The contractor may select specific companies that they feel comfortable working with, or they may put out a broad call for companies to bid on the specific scope. It will typically take several weeks (2 or 3) on larger projects for the specialty trades to compile and submit their bids to the prime contractor. During this time, the prime contractor will also be developing their detailed estimate for their self-perform work scopes along with their general conditions costs, including their management and general work to maintain the site. They may also perform assembly estimates for specialty trade scopes of work so that they have a comparison number when they receive bids from the trade contractors.