The Early Revolution

The run-up to the French Revolution occurred between 1787 and 1789 when the French government was attempting to enact reforms to eliminate the budget deficit. These suggested reforms included increasing taxes on the French Nobility. These attempts were rejected by the Assembly of Notables in 1787, which suggested that the King convene the Estates General which had not met in over 100 years. The government attempted to force reforms through without calling the Estates General, but faced revolts from the courts and unrest in the general population. The Estates General was finally called to meet in the spring of 1789. In the months before the meeting an enormous number of political pamphlets and cartoons appeared and Elected delegates drew up Cahiers of Grievances to bring to the assembly. The following images and documents illustrate many of the concerns of the population.

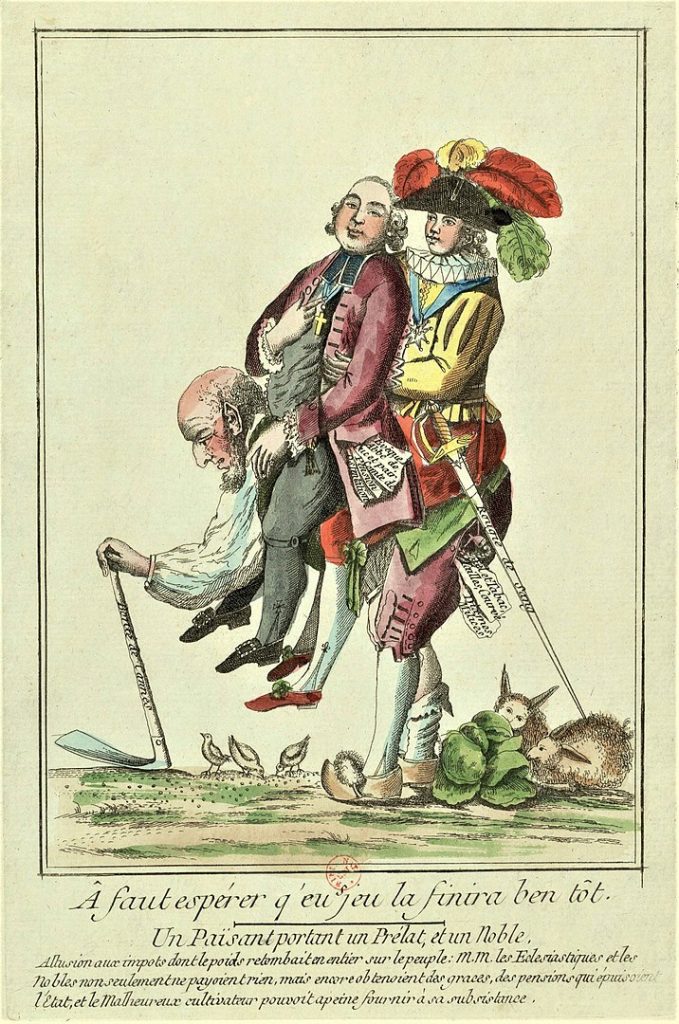

“It must be hoped that the game will finish soon.”

Thousands of images like this were printed over the course of the French Revolution. Single prints like this, usually etchings, were easy and low cost to produce, and their message was easy to understand, literate or not.

Excerpts from What is the Third Estate? – Abbe Sieyès (1789)

In 1789, Abbe Sieyès wrote a pamphlet discussing the role of the third estate in the order of society. He was then elected as a delegate to the Etates General, or General Assembly, from Paris and was made spokesman for the third estate, in spite of his actually belonging to the first estate as a member of the clergy. His pamphlet famously began by asking,

“What is the Third Estate? Everything

What has it been until now in the political order? Nothing

What does it want to be? Something”

The principles that he laid out in this pamphlet appealed to the early revolutionaries, but they began to look far more conservative as the revolution entered its more radical phase. The following excerpts outline some of his arguments around the inequality faced by the members of the third estate and why they should be viewed as more important in the social order.

What is necessary that a nation should subsist and prosper? Individual effort and public functions.

All individual efforts may be included in four classes: 1. Since the earth and the waters furnish crude products for the needs of man, the first class, in logical sequence, will be that of all families which devote themselves to agricultural labor. 2. Between the first sale of products and their consumption or use, a new manipulation, more of less repeated, adds to these products a second value more or less composite. In this manner human industry succeeds in perfecting the gifts of nature, and the crude product increases twofold, tenfold, one hundred-fold in value. Such are the efforts of the second class. 3. Between production and consumption, as well as between the various stages of production, a group of intermediary agents establish themselves, useful both to producers and consumers; these are the merchants and brokers: the brokers who, comparing incessantly the demands of time and place, speculate upon the profit of retention and transportation; merchants who are charged with distribution, in the last analysis, either at wholesale or at retail. This species of utility characterizes the third class. 4. Outside of these three classes of productive and useful citizens, who are occupied with real objects of consumption and use, there is also need in a society of a series of efforts and pains, whose objects are directly useful or agreeable to the individual. This fourth class embraces all those who stand between the most distinguished and liberal professions and the less esteemed services of domestics.

Such are the efforts which sustain society. Who puts them forth? The Third Estate.

Public functions may be classified equally well, in the present state of affairs, under four recognized heads: the sword, the robe, the church, and the administration. It would be superfluous to take them up one by one, for the purpose of showing that everywhere the Third Estate attends to nineteen-twentieths of them, with this distinction; that it is laden with all that which is really painful, with all the burdens which the privileged classes refuse to carry. Do we give the Third Estate credit for this? That this might come about, it would be necessary that the Third Estate should refuse to fill these places, or that it should be less ready to exercise their functions. The facts are well known. Meanwhile they have dared to impose a prohibition upon the order of the Third Estate. They have said to it: “Whatever may be your services, whatever may be your abilities, you shall go thus far; you may not pass beyond!” Certain rare exceptions, properly regarded, are but a mockery, and the terms which are indulged in on such occasions, one insult the more.

If this exclusion is a social crime against the Third Estate; if it is a veritable act of hostility, could it perhaps be said that it is useful to the public weal? Alas! who is ignorant of the effects of monopoly? If it discourages those whom it rejects, is it not well known that it tends to render less able those whom it favors? It is not understood that every employment from which free competition is removed, becomes dearer and less effective?

In setting aside any function whatsoever to serve as an appanage for a distinct class among citizens, is it not to be observed that it is no longer the man alone who does the work that it is necessary to reward, but all the unemployed members of that same caste, and also the entire families of those who are employed as well as those who are not? Is it not to be remarked that since the government has become the patrimony of a particular class, it has been distended beyond all measure; places have been created, not on account of the necessities of the governed, but in the interests of the governing, etc., etc.? Has not attention been called to the fact that this order of things, which is basely and—I even presume to say—beastly respectable with us, when we find it in reading the History of Ancient Egypt or the accounts of Voyages to the Indies, is despicable, monstrous, destructive of all industry, the enemy of social progress; above all degrading to the human race in general, and particularly intolerable to Europeans, etc., etc.? But I must leave these considerations, which, if they increase the importance of the subject and throw light upon it, perhaps, along with the new light, slacken our progress.

It suffices here to have made it clear that the pretended utility of a privileged order for the public service is nothing more than a chimera; that with it all that which is burdensome in this service is performed by the Third Estate; that without it the superior places would be infinitely better filled; that they naturally ought to be the lot and the recompense of ability and recognized services, and that if privileged persons have come to usurp all the lucrative and honorable posts, it is a hateful injustice to the rank and file of citizens and at the same time a treason to the public weal.

Who then shall dare to say that the Third Estate has not within itself all that is necessary for the formation of a complete nation? It is the strong and robust man who has one arm still shackled. If the privileged order should be abolished, the nation would be nothing less, but something more. Therefore, what is the Third Estate? Everything; but an everything shackled and oppressed. What would it be without the privileged order? Everything, but an everything free and flourishing. Nothing can succeed without it, everything would be infinitely better without the others.

It is not sufficient to show that privileged persons, far from being useful to the nation, cannot but enfeeble and injure it; it is necessary to prove further that the noble order does not enter at all into the social organization; that it may indeed be a burden upon the nation, but that it cannot of itself constitute a nation.

In the first place, it is not possible in the number of all the elementary parts of a nation to find a place for the caste of nobles. I know that there are individuals in great number whom infirmities, incapacity, incurable laziness, or the weight of bad habits render strangers to the labors of society. The exception and the abuse are everywhere found beside the rule. But it will be admitted that the less there are of these abuses, the better it will be for the State. The worst possible arrangement of all would be where not alone isolated individuals, but a whole class of citizens should take pride in remaining motionless in the midst of the general movement, and should consume the best part of the product without bearing any part in its production. Such a class is surely estranged to the nation by its indolence.

The noble order is not less estranged from the generality of us by its civil and political prerogatives.

What is a nation? A body of associates, living under a common law, and represented by the same legislature, etc.

It is not evident that the noble order has privileges and expenditures which it dares to call its rights, but which are apart from the rights of the great body of citizens? It departs there from the common order, from the common law. So its civil rights make of it an isolated people in the midst of the great nation. This is truly imperium in imperio.

In regard to its political rights, these also it exercises apart. It has its special representatives, which are not charged with securing the interests of the people. The body of its deputies sit apart; and when it is assembled in the same hall with the deputies of simple citizens, it is none the less true that its representation is essentially distinct and separate: it is a stranger to the nation, in the first place, by its origin, since its commission is not derived from the people; then by its object, which consists of defending not the general, but the particular interest.

The Third Estate embraces then all that which belongs to the nation; and all that which is not the Third Estate, cannot be regarded as being of the nation. What is the Third Estate? It is the whole.

Excerpts from typical Cahiers de doléances from the bailliages of Blios and Versialles

The Cahiers de doléances were lists of grievances drawn up by each of the three estates ( first – the clergy, second – the nobility, and third-everyone else) between January and April of 1789 in advance of the delegates of the Estates General meeting in person. They reflect the concerns across France at the time the Revolution was beginning.

Cahier of the Clergy of Blois

The clergy of the bailiage of Blois have never believed that the constitution needed reform. Nothing is wanting to assure the welfare of the kind and people except that the present constitution should be religiously and inviolable observed.

The constitutional principles concerning which no doubt can be entertained are:

- That France is a true monarchy, where a single man rules and is ruled by law alone.

- That the general laws of the kingdom may be enacted only with the consent of the king and the nation. If the king proposes a law, the nation accepts or rejects it; if the nation demands a law, it is for the king to consent or to reject it; but in either case it is the king alone who upholds the law in his name and attends to its execution.

- That in France we recognize as king him to whom the crown belongs by hereditary right according to the Salic law.

- That we recognize the nation in the States General, composed of the three orders of the kingdom, which are the clergy, the nobility and the third estate.

- That to the king belongs the right of assembling the States General, whenever he considers it necessary.

For the welfare of the kingdom we ask, in common with the whole nation, that this convocation be periodical and fixed, as we particularly desire, at every five years, except in the case of the next meeting, when the great number of matters to be dealt with makes a less remote period desirable.

- That the States General should not vote otherwise than by order.

- That the three orders are equal in power and independent of each other, in such a manner that their unanimous consent is necessary to the expression of the nation’s will.

- That no tax may be laid without the consent of the nation.

- That every citizen has, under the law, a sacred and inviolable right to personal liberty and to the possession of his goods.

We regard lettres de cachet as an abuse, contrary to the constitution. Each citizen without distinction ought to be subject to the laws and other rules of justice, and his trial by any special commission whatsoever not permitted.

. . .

After having observed that the clergy have never enjoyed other privileges in the imposition of taxes than those which were anciently common to all orders of the state, the clergy of the bailliage of Blois declare that for the future they desire to sustain the burden of taxation in common with other subjects of the king.

. . .

The reforms which we judge most necessary in the matter of taxes, and which we particularly recommend to his Majesty’s attention, are the following:

- In the gabelles and aides, which ought to be suppressed, or replaced, if need be with a tax less burdensome;

- In customs duties, which we desire to see restricted to the frontier;

- In registry fees, which have grown to an exorbitant figure. The irregularity of these charges subjects citizens to frequent contentions;

- It is desirable to lessen the disadvantage under which poor country people labor in securing justice in the matter of over-taxation and malversations, on account of the considerable advances which they have to make in order to bring the matter to an issue;

- The shifting of certain taxes might bring them to bear upon various articles of luxury, and especially upon unnecessary articles of domestic use.

. . .

For the purpose of securing a reform of the principal abuses in the administration of justice we very humbly present to His Majesty what appears to us of first importance :

- To divide the too extensive jurisdiction of the sovereign courts;

- To complete the number of judges in each bailliage, in order that sessions may be held with greater regularity;

- To suppress all judges of exceptional courts;

- To suppress all seignorial courts in cases where a justice and necessary officials have not been retained and salaried by the seigneurs;

- To authorize vassals to refuse the jurisdiction of their seigneurs in suits against the said seigneurs;

- To establish in the principal rural places justices of the peace for the trial of minor cases;

- To do away with the sale of judicial and magisterial offices;

- To ordain that these offices shall not be conferred except with the consent of that portion of the nation over which these judges and magistrates are to be placed ;

- To simplify the forms of justice by reducing costs, by accelerating procedure and by suppressing judges’ fees;

- To reform the civil and criminal codes and to diminish the number of customary codes which prevail in various parts of the kingdom, in order to hasten the day, if possible, when there shall be but one national code;

. . .

The nobility ought to be assured of their prerogatives and distinctions in the state, and we very humbly beseech His Majesty to grant these only as a reward for services rendered to our native land. The king is moreover entreated to take into consideration :

- The great number of serious abuses which the right of the chase [or hunt] entails upon agriculturists, and the annoyances caused them by gamekeepers;

- The evils which result from the right of open warren;

- The importance of the regulations concerning pigeon houses, which have almost ceased to be observed ;

- The injustice of depriving the inhabitants of lands adjacent to forests, as has been done in many localities, of the right of pasture, and other rights, which have been accorded them on various accounts.

We beseech His Majesty:

- To take the most effectual means of preventing bankruptcies;

- To fix a term, after which prisoners for debt may recover their liberty;

- To interest himself in ameliorating the condition of negroes in the colonies.

Impressed as we are with the great influence of public education upon the religion, morals and prosperity of the state, we beseech His Majesty to favor it with all his power. We desire :

- That public instruction shall be absolutely gratuitous, as well in the universities as in the provincial schools;

- That the provincial colléges shall be entrusted by preference to the corporations of the regular clergy;

- That many corporations of the regular clergy, which at present are not occupied with the instruction of youth, shall apply themselves to this work, and thereby render themselves more useful to the state;

. . .

(This document, recorded in the clerk’s office of the bailliage of Blois, is signed: “Abbé Ponthèves, President.” Then follow the signatures of 53 parish priests, 14 priors, 8 canons, 8 priests, 3 deans, 3 abbots, 3 curates, 1 chaplain, 1 friar, 1 deacon and 27 persons unclassified.)

Cahier of the Nobility of Blois

The misfortune of France arises from the fact that it has never had a fixed constitution. A virtuous and sympathetic king seeks the counsels and cooperation of the nation to establish one; let us hasten to accomplish his desires; let us hasten to restore to his soul that peace which his virtues merit. The principles of this constitution should be simple; they may be reduced to two: Security for person, security for property; because, in fact, it is from these two fertile principles that all organization of the body politic takes its rise.

. . .

In order to assure the exercise of this first and most sacred of the rights of man, we ask that no citizen may be exiled, arrested or held prisoner except in cases contemplated by the law and in accordance with a decree originating in the regular courts of justice.

. . .

From the right of personal liberty arises the right to write, to think, to print and to publish, with the names of authors and publishers, all kinds of complaints and reflections upon public and private affairs, limited by the right of every citizen to seek in the established courts legal redress against author or publisher, in case of defamation or injury; limited also by all restrictions which the States General may see fit to impose in that which concerns morals and religion. The violation of the secrecy of letters is still an infringement upon the liberty of citizens; and since the sovereign has assumed the exclusive right of transporting letters throughout the kingdom, and this has become a source of public revenue, such carriage ought to be made under the seal of confidence.

. . .

In accordance with this principle the nobility of the bailliage of Blois believes itself in duty bound to lay at the feet of the nation all the pecuniary exemptions which it has enjoyed or might have enjoyed up to this time, and it offers to contribute to the public needs in proportion with other citizens, upon condition that the names of taille and corvée be suppressed and all direct taxes be comprised in a single land tax in money.

. . .

We shall not close this article without asking:

- That legal forms accompanying actions arising from the seizure and sale of property, administrations and creditors’ mandates, and other actions in which a large number of persons are interested, shall be abridged and simplified;

- That the file of notarial records shall be sacred; that they shall be placed, after an interval of time has elapsed, in a public place, where all citizens may have access to them;

- That there shall be established in each rural parish a court of reconciliation, composed of the seigneur, the parish priest and certain elderly men, for the purpose of amicably settling disputes and preventing suits at law.

. . .

The principal assistance which agriculture awaits at this moment from the representatives of the nation is as follows:

- 1. Absolute freedom in the sale and circulation of grain and produce;

- A regulation favoring the redemption of socome and other burdensome taxes, the drainage of swamps, the division of communal lands;

- Government encouragement in the production of better grades of wool and in the breeding of cattle;

- Abolition of sealers of weights and measures ;

- Establishments for weaving, for the manufacture of the coarser fabrics in the villages, to give employment to the country people during the idle period of the year;

- Better facilities for the education of children; elementary text-books, adapted to their capacity, where the rights of man and the social duties shall be clearly set forth;

- More expert surgeons and experienced midwives, etc.

Deputies ought to find assistance toward these ends in the agricultural societies, in the learned associations of the capital and in the great number of works which have been published in the last few years. They should not lose sight of the fact that agriculture is the foremost of all the arts; that it is the source of reviving prosperity; agriculture it is that furnishes to all manufacturers the raw materials upon which industry is exercised, and to commerce the materials of exchange; it furnishes subsistence to all; and, finally, it is in agriculture that the strength of the nation resides.

. . .

In order to accomplish this great object the nobility of the bailliage of Blois demand :

That the States General about to assemble shall be permanent and shall not be dissolved until the constitution be established; but in case the labors connected with the establishment of the constitution be prolonged beyond a space of two years, the assembly shall be reorganized with new deputies freely and regularly elected. That a fundamental and constitutional law shall assure forever the periodical assembly of the States General at frequent intervals, in such a manner that they may assemble and organize themselves at a fixed time and place, without the concurrence of any act emanating from the executive power. That the legislative power shall reside exclusively in the assembly of the nation, under the sanction of the king, and shall not be exercised by any intermediate body during the recess of the States General. That the king shall enjoy the full extent of executive power necessary to insure the execution of the laws; but that he shall not be able in any event to modify the laws without the consent of the nation. That the form of the military oath shall be changed, and the troops promise obedience and fidelity to the king and the nation. That taxes may not be imposed without the consent of the nation; that taxes may be granted only for a specified time, and for no longer than the next meeting of the States General.

. . .

(The cahier is signed by 7 marquises, 7 counts, 3 viscounts, 3 barons, 9 knights, and 64 persons without special title.)

Cahier of the Third Estate of Versailles

Art. 1. The power of making laws resides in the king and the nation.

Art. 2. The nation being too numerous for a personal exercise of this right, has confided its trust to representatives freely chosen from all classes of citizens. These representatives constitute the national assembly.

Art. 3. Frenchmen should regard as laws of the kingdom those alone which have been prepared by the national assembly and sanctioned by the king.

. . .

Art. 11. Personal liberty, proprietary rights and the security of citizens shall be established in a clear, precise and irrevocable manner. All lettres de cachet shall be abolished forever, subject to certain modifications which the States General may see fit to impose.

Art. 12. And to remove forever the possibility of injury to the personal and proprietary rights of Frenchmen, the jury system shall be introduced in all criminal cases, and in civil cases for the determination of fact, in all the courts of the realm.

Art. 13. All persons accused of crimes not involving the death penalty shall be released on bail within twenty-four hours. This release shall be pronounced by the judge upon the decision of the jury.

Art. 14. All persons who shall have been imprisoned upon suspicion, and afterwards proved innocent, shall be entitled to satisfaction and damages from the state, if they are able to show that their honor or property has suffered injury.

Art. 15. A wider liberty of the press shall be accorded, with this provision alone: that all manuscripts sent to the printer shall be signed by the author, who shall be obliged to disclose his identity and bear the responsibility of his work; and to prevent judges and other persons in power from taking advantage of their authority, no writing shall be held a libel until it is so determined by twelve jurors, chosen according to the forms of a law which shall be enacted upon this subject.

Art. 16. Letters shall never be opened in transit; and effectual measures shall be taken to the end that this trust shall remain inviolable.

Art. 17. All distinctions in penalties shall be abolished; and crimes committed by citizens of the different orders shall be punished irrespectively, according to the same forms of law and in the same The States General shall seek to bring it about that the effects of transgression shall be confined to the individual, and shall not be reflected upon the relatives of the transgressor, themselves innocent of all participation.

Art. 18. Penalties shall in all cases be moderate and proportionate to the crime. All kinds of torture, the rack and the stake, shall be abolished. Sentence of death shall be pronounced only for atrocious crimes and in rare instances, determined by the law.

Art. 19. Civil and criminal laws shall be reformed.

Art. 20. The military throughout the kingdom shall be subject to the general law and to the civil authorities, in the same manner as other citizens.

Art. 21. No tax shall be legal unless accepted by the representatives of the people and sanctioned by the king.

Art. 22. Since all Frenchmen receive the same advantage from the government, and are equally interested in its maintenance, they ought to be placed upon the same footing in the matter of taxation.

. . .

Art. 35. The present militia system, which is burdensome, oppressive and humiliating to the people, shall be abolished; and the States General shall devise means for its reformation.

Art. 36. A statement of pensions shall be presented to the States

General; they shall be granted only in moderate amounts, and then only for services rendered. The total annual expenditure for this purpose should not exceed a fixed sum. A list of pensions should be printed and made public each year.

Art. 37. Since the nation undertakes to provide for the personal

expenses of the sovereign, as well as for the crown and state, the law providing for the inalienability of the domain shall be repealed. As a result, all parcels of the domain immediately in the king’s possession, as well as those already pledged, and for the forests of His Majesty as well, shall be sold, and transferred in small lots, in so far as possible, and always at public auction to the highest bidder; and the proceeds applied to the reduction of the public debt. In the meanwhile all woods and forests shall continue to be controlled and administered, whoever may be the actual proprietors, according to the provisions of the law of 1669.

. . .

Art. 41. All general and particular statements and accounts relative to the administration shall be printed and made public each year.

Art. 42. The coinage may not be altered without the consent of the Estates; and no bank established without their approval.

Art. 43. A new subdivision shall be made of the provinces of the realm ; provincial estates shall be established, members of which, notexcepting their presidents, shall be elected.

Art. 44. The constitution of the provincial estates shall be uniform throughout the kingdom, and fixed by the States General. Their powers shall be limited to the interior administration of the provinces, under the supervision of His Majesty, who shall communicate to them the national laws which have received the consent of the States General and the royal sanction: to which laws all the provincial estates shall be obliged to submit without reservation.

Art. 45. All members of the municipal assemblies of towns and villages shall be elected. They may be chosen from all classes of citizens. All municipal offices now existing shall be abolished; and their redemption shall be provided for by the States General.

Art. 46. All offices and positions, civil, ecclesiastical and military, shall be open to all orders; and no humiliating and unjust exceptions (in the case of the third estate), destructive to emulation and injurious to the interests of the state, shall be perpetuated.

Art. 47. The right of aubaine shall be abolished with regard to all nationalities. All foreigners, after three years’ residence in the kingdom, shall enjoy the rights of citizenship.

Art. 48. Deputies of French colonies in America and in the Indies, which form an important part of our possessions, shall be admitted to the States General, if not at the next meeting, at least at the one following.

Art. 49. All relics of serfdom, agrarian or personal, still remaining in certain provinces, shall be abolished.

Art. 50. New laws shall be made in favor of the negroes in our colonies; and the States General shall take measures towards the abolition of slavery. Meanwhile let a law be passed, that negroes in the colonies who desire to purchase their freedom, as well as those whom their masters are willing to set free, shall no longer be compelled to pay a tax to the domain.

. . .

Art. 66. The deputies of the prévôté and vicomté of Paris shall be instructed to unite themselves with the deputies of other provinces, in order to join with them in securing, as soon as possible, the following abolitions :

- Of the taille ;

- Of the gabelle;

- Of the aides ;

- Of the corvée ;

- Of the ferme of tobacco;

- Of the registry-duties;

- Of the free-hold tax;

- Of the taxes on leather;

- Of the government stamp upon iron;

- Of the stamps upon gold and silver;

- Of the interprovincial customs duties;

- Of the taxes upon fairs and markets;

Finally, of all taxes that are burdensome and oppressive, whether on account of their nature or of the expense of collection, or because they have been paid almost wholly by agriculturists and by the poorer classes. They shall be replaced with other taxes, less complicated and easier of collection, which shall fall alike upon all classes and orders of the state without exception.

Art. 67. We demand also the abolition of the royal preserves

(capitaineries);

- Of the game laws;

- Of jurisdictions of prévôtés;

- Of banalités;

- Of tolls;

- Of useless authorities and governments in cities and provinces.

Art. 68. We solicit the establishment of public granaries in the provinces, under the control of the provincial estates, in order that by accumulating reserves during years of plenty, famine and excessive dearness of grain, such as we have experienced in the past, may be prevented.

Art. 69. We solicit also the establishment of free schools in all country parishes.

Art. 70. We demand, for the benefit of commerce, the abolition of all exclusive privileges :

- The removal of customs barriers to the frontiers;

- The most complete freedom in trade;

- The revision and reform of all laws relative to commerce;

- Encouragement for all kinds of manufacture, viz.: premiums,

bounties and advances; - Rewards to artisans and laborers for useful inventions.

- The communes desire that prizes and rewards shall always be preferred to exclusive privileges, which extinguish emulation and lessen competition.

Art. 71. We demand the suppression of various hindrances, such as stamps, special taxes, inspections; and the annoyances and visitations, to which many manufacturing establishments, particularly tanneries, are subjected.

Art. 72. The States General are entreated to devise means for abolishing guild organizations, indemnifying the holders of masterships; and to fix by the law the conditions under which the arts, trades and professions may be followed without the payment of an admission tax, and at the same time to provide that public security and confidence be undisturbed.

. . .

Art. 84. That inheritances shall be divided equally among heritors of the same degree, without regard to sex or right of primogeniture, nor to the status of the co-participants, and without distinction between nobles and non-nobles.

. . .

Art. 88. That all state prisons shall be abolished, and that means shall be taken to put all other prisons in better sanitary condition.

Art. 89. That it may please the States General to provide means for securing a uniformity of weights and measures throughout the kingdom.

Source:

Translations and reprints from the original sources of European history :

series for 1899

Typical cahiers of 1789. Edited by Merrick Whitcomb. (Philadelphia, PA: The Department of History of the University of Pennsylvania; 1901, c1897). Accessed at Hathi Trust https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100883624

Questions for Discussion:

- How does Sieyès’ piece characterize the value of the Third Estate to society? What makes them important in his view?

- In the Cahiers, what do the three estates seem to agree upon and in what places do their views seem to differ?

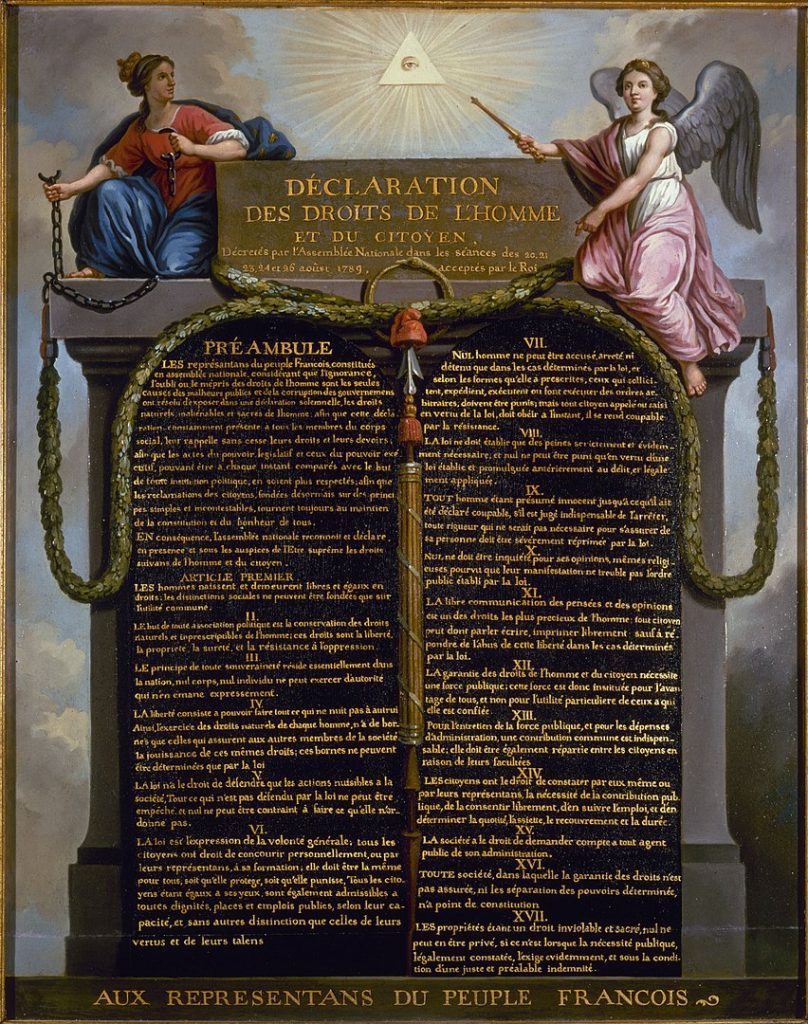

Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen

The Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen was issued on August 27, 1789. It was written as a preamble to the constitution the National Assembly hoped to write in the coming months and its text would be influential on several European constitutions that would be created in the following century. This image by Jean-Jacques-François le Barbier was made in 1789 and reproduced many times as a celebration of the document.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (French: La Déclaration des droits de l’Homme et du citoyen) is one of the fundamental documents of the French Revolution, defining a set of individual rights and collective rights of all of the estates as one. Influenced by the doctrine of natural rights, these rights are universal: they are supposed to be valid in all times and places, pertaining to the human nature itself. The Declaration was adopted August 26, 1789 (some sources say August 27), by the National Constituent Assembly (Assemblée nationale constituante), as the first step toward writing a constitution. It sets forth fundamental rights not only of French citizens but acknowledges these rights to all men without exception, making it a precursor to international human rights instruments.

The representatives of the French people, constituted into a National Assembly, considering that ignorance, forgetfulness or contempt of the rights of man are the sole causes of public misfortunes and of the corruption of governments, are resolved to expose, in a solemn declaration, the natural, inalienable and sacred rights of man, so that that declaration, constantly present to all members of the social body, points out to them without cease their rights and their duties; so that the acts of the legislative power and those of the executive power, being at every instant able to be compared with the goal of any political institution, are very respectful of it; so that the complaints of the citizens, founded from now on simple and incontestable principles, turn always to the maintenance of the Constitution and to the happiness of all.

In consequence, the National Assembly recognizes and declares, in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following rights of man and of the citizen:

Article I – Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions can be founded only on the common good.

Article II – The goal of any political association is the conservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression.

Article III – The principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation. No body, no individual can exert authority which does not emanate expressly from it.

Article IV – Liberty consists of doing anything which does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has only those borders which assure other members of the society the enjoyment of these same rights. These borders can be determined only by the law.

Article V – The law has the right to forbid only actions harmful to society. Anything which is not forbidden by the law cannot be impeded, and no one can be constrained to do what it does not order.

Article VI – The law is the expression of the general will. All the citizens have the right of contributing personally or through their representatives to its formation. It must be the same for all, either that it protects, or that it punishes. All the citizens, being equal in its eyes, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents.

Article VII – No man can be accused, arrested nor detained but in the cases determined by the law, and according to the forms which it has prescribed. Those who solicit, dispatch, carry out or cause to be carried out arbitrary orders, must be punished; but any citizen called or seized under the terms of the law must obey at once; he renders himself culpable by resistance.

Article VIII – The law should establish only penalties that are strictly and evidently necessary, and no one can be punished but under a law established and promulgated before the offense and legally applied.

Article IX – Any man being presumed innocent until he is declared culpable, if it is judged indispensable to arrest him, any rigor which would not be necessary for the securing of his person must be severely reprimanded by the law.

Article X – No one may be disturbed for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not trouble the public order established by the law.

Article XI – The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, except to respond to the abuse of this liberty, in the cases determined by the law.

Article XII – The guarantee of the rights of man and of the citizen necessitates a public force: this force is thus instituted for the advantage of all and not for the particular utility of those in whom it is trusted.

Article XIII – For the maintenance of the public force and for the expenditures of administration, a common contribution is indispensable; it must be equally distributed between all the citizens, according to their ability to pay.

Article XIV – Each citizen has the right to ascertain, by himself or through his representatives, the need for a public tax, to consent to it freely, to know the uses to which it is put, and of determining the proportion, basis, collection, and duration.

Article XV – The society has the right of requesting account from any public agent of its administration.

Article XVI – Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured, nor the separation of powers determined, has no Constitution.

Article XVII – Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of private usage, if it is not when the public necessity, legally noted, evidently requires it, and under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

Questions for Discussion:

- What does this declaration tell you about the Ancien Regime that was being replaced by the new constitution created by the National Assembly?

- How do the ideas in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen connect back to the ideas of the Enlightenment?

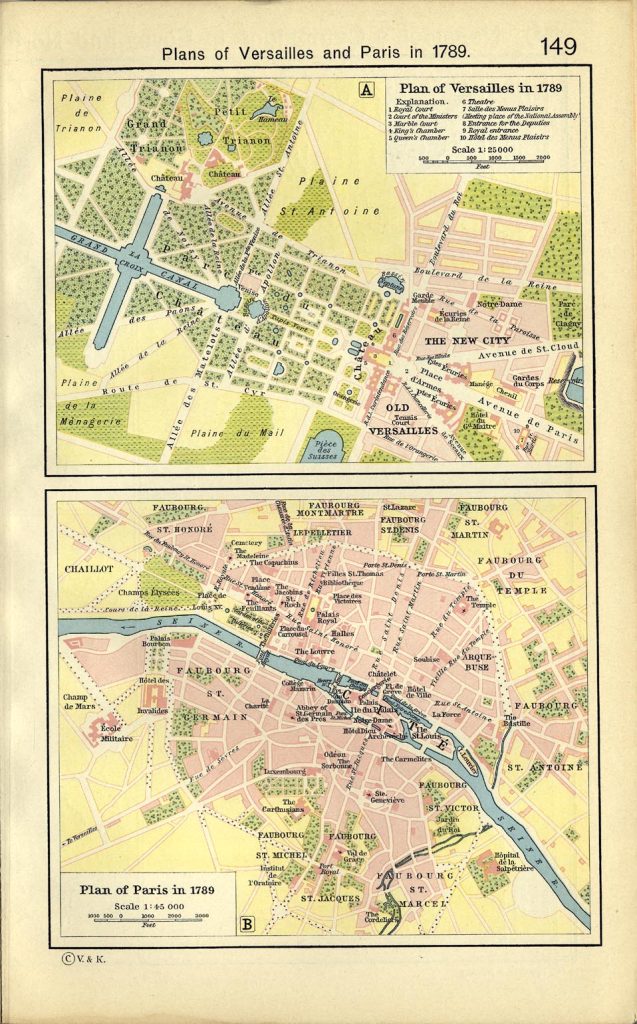

The following maps depict Versailles and Paris in 1789. The National Assembly met in Paris from October 1789 to September 1791. During this same time frame, the King and his family moved from Versailles to Paris, following the women’s march on Versailles urging action over the price of bread. Protesters had entered and ransacked the Royal apartments, convincing the king that a return to Paris, escorted by the National Guard, would be advisable.

The Revolution Becomes Radical – the Terror

On June 20th, 1791, the King and his family left the Tuileries Palace in Paris disguised as servants to a supposed Russian baroness. The escape plan was to head to Montmédy near the border with Austria, and there head up royalist troops for a counter-revolution. The royal family was arrested in the town of Varennes only 31 miles from their destination. After this flight, the abolition of the monarchy became a central goal of the more radical revolutionaries, who ended up taking over the National Assembly.

Account of Louis XVI’s Execution from the London Packet or New Lloyd’s Evening Post January 23, 1793

From various letters before us, contradictory in some particulars, but agreeing in the main, received yesterday as well as from the Parisian papers arrived this morning, we are enabled to lay before the public the following narrative.

Agreeable to a Proclamation of the provisional Executive Council, published on this Sunday, the devoted Monarch of France was taken from the Temple soon after eight o’clock in the morning of Monday last; he wore a great coat of the fashion of those who are commonly worn without other coats by the French, of a dark colour, black silk breeches and stockings, altogether neat, and his hair was dressed. He was in the coach of the Mayor; there were in the coach with him hi confessor and two military men.

Proceeding by the rout, which had been marked out by the executive Council, the way was so entirely occupied by the military, and the innumerable officers of the civil power, that the populace were entirely excluded. Those who appeared at the windows were ordered away.

The scaffold was erected according to the directions of the council, near the spot on which lately stood the magnificent statue of Louis the Fifteenth in the square, to which it gave a name: this erection was elevated at an unusual height from the ground, and on it was placed the dreadful guillotine.

By every account, it appears that the king advance towards this awful apparatus with a calmness which astonished everyone . – He looked around upon the multitude, as if desirous to address them – this multitude were composed of the creatures of the day, the hired instruments of democratic vengeance; the mass of the people ,that people to whom he before had in vain expressed a wish to appeal, were kept at a distance, too great in general for them to hear anything he might have to say.

When he prepared to speak, all was for a moment silent; the military music stopped, till ordered again to proceed by savage directors of the sacrifice, and the voice of the dying King was drowned in clamour: however, he was her distinctly to pronounce – “I die innocent, – I forgive –”.

The council head so given instructions that the execution might be over at noon; yet such was the haste of the immediate conductors, as if thirsting to luxuriate in the blood of the victim, that near two hours before noon all was over!

As the Executioner raised the bleeding head, the infernals around rent the air with repeated shouts of “Vive la Nation!” After the death of the king, those who were nearest the scene forced themselves between the horses of the military that formed a square round the scaffold and dipped their handkerchiefs in his blood, which ran in copious streams upon the ground; others, smeared the points of their pikes, swords, and bayonets with it, crying out – “Behold the blood of a tyrant! Thus perish all the tyrants of the Earth!” The surrounding spectators at a distance, uttering no other sounds than groans and signs. The military music struck up Ca Ira!

Questions for Discussion

- What is the tone of this coverage, for an English Audience, about the death of Louis XVI?

- How does the description of the crowd reveal revolutionary zeal? What is the significance of the crowds actions after the King has been guillotined?

The Law of Suspects – Decree of the French National Convention

Decree that orders the arrest of Suspect People.

-

- Of 17 September 1793.

The National Convention, having heard the report of its legislative committee on the method of bringing into effect its decree of last 12 August, decrees the following:

Art. I. Immediately after the publication of this decree, all suspect people who are to be found on the territory of the Republic, and who are still at large, will be put under arrest.

II. People considered suspects are:

- Those who, either by their conduct, or their associations, or by their words or writings, have shown themselves to be partisans of tyranny or of federalism, and enemies of liberty;

- Those who cannot justify, in the manner prescribed by the decree of last 21 March, their means of existence and the acquittal of their civic duties;

- Those who have been denied certificates of good citizenship;

- Public officials who have been suspended or discharged from their functions by the National Convention or its commissioners and have not been reinstated, notably those who have been or ought to be discharged under the law of last 14 August;

- Those former nobles, with their husbands, wives, fathers, mothers, sons or daughters, brothers or sisters, and agents of émigrés, who have not consistently demonstrated their commitment to the Revolution;

- Those who have emigrated during the interval between 1 July 1789 and the publication of the law of 8 April 1792, even if they have returned to France within the time prescribed by that law, or earlier;

Exercises

- What does the “Law of Suspects” reveal about who the Revolutionary government was concerned about when it passed? Why were these particular groups a potential problem to the success of the Revolution?

- What do these laws highlight about who or what is valued, and who or what is not, in Revolutionary France?

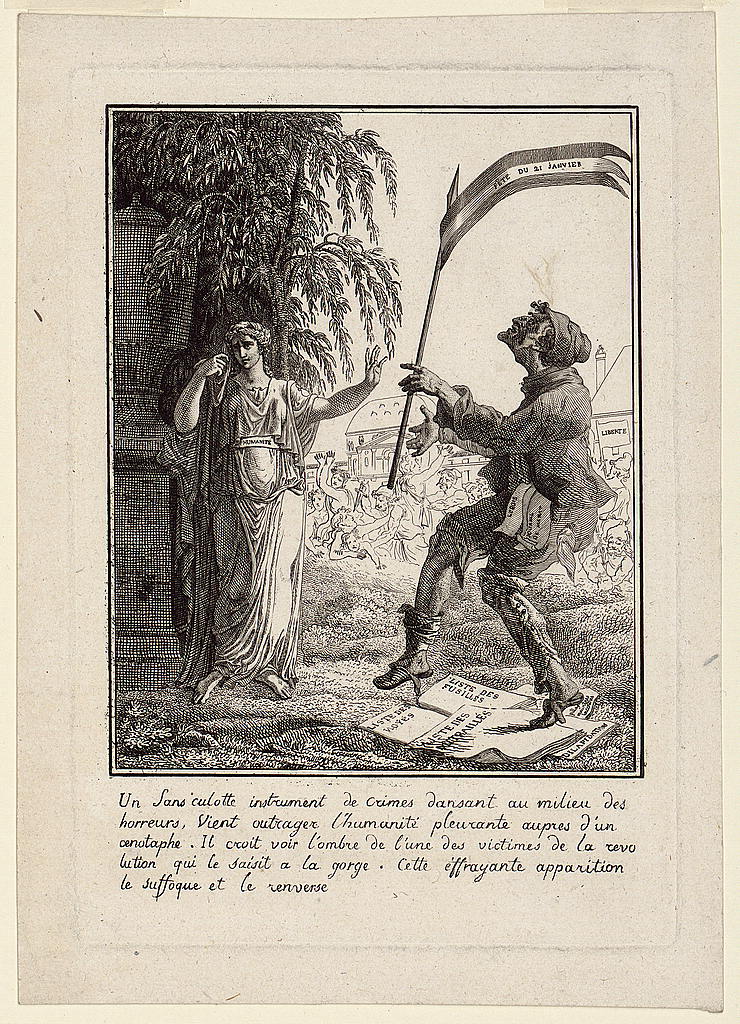

- Examine the drawing closely – what details reveal the point of view it represents? What does the viewer need to know to make sense of the image?

Additional Resources

“The French Revolution,” by Harrison W. Mark, World History Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org/French_Revolution/

“The Constitution of 1793,” at Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution https://revolution.chnm.org/d/430

“Reign of Terror” by Harrison W. Mark on the World History Encyclopedia site, https://www.worldhistory.org/Reign_of_Terror/