From the earliest voyages of Europeans to the Americas, overseas trade and colonization boosted European economies, influenced their political developments, and impacted their culture. New foods, medicines, animals, diseases, and peoples were introduced to Europeans, and by Europeans to the various places they traveled. But colonization also decimated Native New World populations, damaged cultures, and destroyed lives. The Atlantic Slave Trade, which supported the growth in the trading products such as sugar, tobacco, cotton, and coffee, uprooted millions, many of whom died at the hands of their captors. The cost to human life and human dignity was horrific and left a legacy that the world still struggles with to this day.

Slavery and the Slave Trade

This first source gives us a glimpse of what the slave trade was like from the eyes of Olaudah Equiano, who was known for most of his life, after being enslaved, as Gustavus Vassa. These excerpts from his autobiography describe how he was captured by slavers as a child, his voyage to Barbados on a slave ship, and the sale at the end of this voyage.

From Barbados, Equiano was sent on to Virginia, was sold on to a lieutenant in the Royal Navy who kept him for many years, then to a Navy Captian, and finally to Robert King, an American merchant, and a Quaker who gave him the opportunity to earn the money to purchase his freedom. Once free, he moved to Britain and became involved in the abolitionist movement, speaking often in public about his experiences. Friends in the movement encouraged him to write his autobiography which he did in 1789.

Excerpts from The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African – Written by Himself

I have already acquainted the reader with the time and place of my birth. My father, besides many slaves, had a numerous family, of which seven lived to grow up, including myself and a sister, who was the only daughter. As I was the youngest of the sons, I became, of course, the greatest favorite with my mother, and was always with her; and she used to take particular pains to form my mind. I was trained up from my earliest years in the art of war; my daily exercise was shooting and throwing javelins; and my mother adorned me with emblems, after the manner of our greatest warriors. In this way, I grew up till I was turned the age of eleven, when an end was put to my happiness in the following manner.

Generally, when the grown people in the neighborhood were gone far in the fields to labor, the children assembled together in some of the neighbors’ premises to play; and commonly some of us used to get up a tree to look out for any assailant, or kidnapper, that might come upon us; for they sometimes took those opportunities of our parents’ absence to attack and carry off as many as they could seize. One day, as I was watching at the top of a tree in our yard, I saw one of those people come into the yard of our next neighbor but one, to kidnap, there being many stout young people in it. Immediately on this I gave the alarm of the rogue, and he was surrounded by the stoutest of them, who entangled him with cords, so that he could not escape till some of the grown people came and secured him. But alas! ere long it was my fate to be thus attacked, and to be carried off, when none of the grown people were nigh.

One day, when all our people were gone out to their works as usual, and only I and my dear sister were left to mind the house, two men and a woman got over our walls, and in a moment seized us both, and, without giving us time to cry out, or make resistance, they stopped our mouths, and ran off with us into the nearest wood. Here they tied our hands, and continued to carry us as far as they could, till night came on, when we reached a small house, where the robbers halted for refreshment, and spent the night. We were then unbound, but were unable to take any food; and, being quite overpowered by fatigue and grief, our only relief was some sleep, which allayed our misfortune for a short time. The next morning we left the house, and continued traveling all the day. For a long time we had kept the woods, but at last we came into a road which I believed I knew. I had now some hopes of being delivered; for we had advanced but a little way before I discovered some people at a distance, on which I began to cry out for their assistance: but my cries had no other effect than to make them tie me faster and stop my mouth, and then they put me into a large sack. They also stopped my sister’s mouth, and tied her hands; and in this manner we proceeded till we were out of the sight of these people. When we went to rest the following night they offered us some victuals; but we refused it; and the only comfort we had was in being in one another’s arms all that night, and bathing each other with our tears. But alas! we were soon deprived of even the small comfort of weeping together. The next day proved a day of greater sorrow than I had yet experienced; for my sister and I were then separated, while we lay clasped in each other’s arms. It was in vain that we besought them not to part us; she was torn from me, and immediately carried away, while I was left in a state of distraction not to be described. I cried and grieved continually; and for several days I did not eat anything but what they forced into my mouth. At length, after many days traveling, during which I had often changed masters, I got into the hands of a chieftain, in a very pleasant country.

. . .

Olaudah Equiano tells of his existence as a slave in Africa, being sold from one master to another until he reached the coast. He then describes his experience of traveling on a slave ship and of being sold on his arrival in Virginia.

. . .

The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled and tossed up to see if I were sound by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me. Their complexions too differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the language they spoke, (which was very different from any I had ever heard) united to confirm me in this belief. Indeed such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my own country. When I looked round the ship too and saw a large furnace or copper boiling, and a multitude of black people of every description chained together, every one of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate; and, quite overpowered with horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted. When I recovered a little I found some black people about me, who I believed were some of those who brought me on board, and had been receiving their pay; they talked to me in order to cheer me, but all in vain. I asked them if we were not to be eaten by those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and loose hair. They told me I was not; and one of the crew brought me a small portion of spirituous liquor in a wine glass; but, being afraid of him, I would not take it out of his hand. One of the blacks therefore took it from him and gave it to me, and I took a little down my palate, which, instead of reviving me, as they thought it would, threw me into the greatest consternation at the strange feeling it produced, having never tasted any such liquor before. Soon after this the blacks who brought me on board went off, and left me abandoned to despair.

I now saw myself deprived of all chance of returning to my native country, or even the least glimpse of hope of gaining the shore, which I now considered as friendly; and I even wished for my former slavery in preference to my present situation, which was filled with horrors of every kind, still heightened by my ignorance of what I was to undergo. I was not long suffered to indulge my grief; I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life: so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything.

I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and, on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across I think the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. I had never experienced anything of this kind before; and although, not being used to the water, I naturally feared that element the first time I saw it, yet nevertheless, could I have got over the nettings, I would have jumped over the side, but I could not; and, besides, the crew used to watch us very closely who were not chained down to the decks, lest we should leap into the water: and I have seen some of these poor African prisoners most severely cut for attempting to do so, and hourly whipped for not eating. This indeed was often the case with myself.

In a little time after, amongst the poor chained men, I found some of my own nation, which in a small degree gave ease to my mind. I inquired of them what was to be done with us; they gave me to understand we were to be carried to these white people’s country to work for them. I then was a little revived, and thought, if it were no worse than working, my situation was not so desperate: but still I feared I should be put to death, the white people looked and acted, as I thought, in so savage a manner; for I had never seen among any people such instances of brutal cruelty; and this not only shown towards us blacks, but also to some of the whites themselves. One white man in particular I saw, when we were permitted to be on deck, flogged so unmercifully with a large rope near the foremast, that he died in consequence of it; and they tossed him over the side as they would have done a brute. This made me fear these people the more; and I expected nothing less than to be treated in the same manner. I could not help expressing my fears and apprehensions to some of my countrymen: I asked them if these people had no country, but lived in this hollow place (the ship): they told me they did not, but came from a distant one. ‘Then,’ said I, ‘how comes it in all our country we never heard of them?’ They told me because they lived so very far off. I then asked where were their women? had they any like themselves? I was told they had: ‘and why,’ said I, ‘do we not see them?’ they answered, because they were left behind. I asked how the vessel could go? they told me they could not tell; but that there were cloths put upon the masts by the help of the ropes I saw, and then the vessel went on; and the white men had some spell or magic they put in the water when they liked in order to stop the vessel. I was exceedingly amazed at this account, and really thought they were spirits. I therefore wished much to be from amongst them, for I expected they would sacrifice me: but my wishes were vain; for we were so quartered that it was impossible for any of us to make our escape.

While we stayed on the coast I was mostly on deck; and one day, to my great astonishment, I saw one of these vessels coming in with the sails up. As soon as the whites saw it, they gave a great shout, at which we were amazed; and the more so as the vessel appeared larger by approaching nearer. At last she came to an anchor in my sight, and when the anchor was let go I and my countrymen who saw it were lost in astonishment to observe the vessel stop; and were not convinced it was done by magic. Soon after this the other ship got her boats out, and they came on board of us, and the people of both ships seemed very glad to see each other. Several of the strangers also shook hands with us black people, and made motions with their hands, signifying, I suppose, we were to go to their country; but we did not understand them.

At last, when the ship we were in had got in all her cargo, they made ready with many fearful noises, and we were all put under deck, so that we could not see how they managed the vessel. But this disappointment was the least of my sorrow. The stench of the hold, while we were on the coast, was so intolerably loathsome, that it was dangerous to remain there for any time, and some of us had been permitted to stay on the deck for the fresh air; but now that the whole ship’s cargo were confined together, it became absolutely pestilential. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable. Happily perhaps for myself, I was soon reduced so low here that it was thought necessary to keep me almost always on deck; and from my extreme youth I was not put in fetters. In this situation I expected every hour to share the fate of my companions, some of whom were almost daily brought upon deck at the point of death, which I began to hope would soon put an end to my miseries. Often did I think many of the inhabitants of the deep much happier than myself. I envied them the freedom they enjoyed, and as often wished I could change my condition for theirs. Every circumstance I met with served only to render my state more painful, and heighten my apprehensions, and my opinion of the cruelty of the whites.

One day they had taken a number of fishes; and when they had killed and satisfied themselves with as many as they thought fit, to our astonishment who were on the deck, rather than give any of them to us to eat as we expected, they tossed the remaining fish into the sea again, although we begged and prayed for some as well as we could, but in vain; and some of my countrymen, being pressed by hunger, took an opportunity, when they thought no one saw them, of trying to get a little privately; but they were discovered, and the attempt procured them some very severe floggings. One day, when we had a smooth sea and moderate wind, two of my wearied countrymen who were chained together (I was near them at the time), preferring death to such a life of misery, somehow made it through the nettings and jumped into the sea: immediately another quite dejected fellow, who, on account of his illness, was suffered to be out of irons, also followed their example; and I believe many more would very soon have done the same if they had not been prevented by the ship’s crew, who were instantly alarmed. Those of us that were the most active were in a moment put down under the deck, and there was such a noise and confusion amongst the people of the ship as I never heard before, to stop her, and get the boat out to go after the slaves. However two of the wretches were drowned, but they got the other, and afterwards flogged him unmercifully for thus attempting to prefer death to slavery.

In this manner, we continued to undergo more hardships than I can now relate, hardships which are inseparable from this accursed trade. Many a time we were near suffocation from the want of fresh air, which we were often without for whole days together. This, and the stench of the necessary tubs, carried off many. During our passage I first saw flying fishes, which surprised me very much: they used frequently to fly across the ship, and many of them fell on the deck. I also now first saw the use of the quadrant; I had often with astonishment seen the mariners make observations with it, and I could not think what it meant. They at last took notice of my surprise; and one of them, willing to increase it, as well as to gratify my curiosity, made me one day look through it. The clouds appeared to me to be land, which disappeared as they passed along. This heightened my wonder; and I was now more persuaded than ever that I was in another world, and that everything about me was magic.

At last, we came in sight of the island of Barbados, at which the whites on board gave a great shout, and made many signs of joy to us. We did not know what to think of this; but as the vessel drew nearer we plainly saw the harbor, and other ships of different kinds and sizes; and we soon anchored amongst them off Bridge Town. Many merchants and planters now came on board, though it was in the evening. They put us in separate parcels, and examined us attentively. They also made us jump, and pointed to the land, signifying we were to go there. We thought by this we should be eaten by these ugly men, as they appeared to us; and, when soon after we were all put down under the deck again, there was much dread and trembling among us, and nothing but bitter cries to be heard all the night from these apprehensions, insomuch that at last the white people got some old slaves from the land to pacify us. They told us we were not to be eaten, but to work, and were soon to go on land, where we should see many of our country people. This report eased us much; and sure enough, soon after we were landed, there came to us Africans of all languages. We were conducted immediately to the merchant’s yard, where we were all pent up together like so many sheep in a fold, without regard to sex or age.

As every object was new to me every thing I saw filled me with surprise. What struck me first was that the houses were built with stories, and in every other respect different from those in Africa: but I was still more astonished on seeing people on horseback. I did not know what this could mean; and indeed I thought these people were full of nothing but magical arts. While I was in this astonishment one of my fellow prisoners spoke to a countryman of his about the horses, who said they were the same kind they had in their country. I understood them, though they were from a distant part of Africa, and I thought it odd I had not seen any horses there; but afterwards, when I came to converse with different Africans, I found they had many horses amongst them, and much larger than those I then saw.

We were not many days in the merchant’s custody before we were sold in their usual manner, which is this. On a signal given, (as the beat of a drum) the buyers rush at once into the yard where the slaves are confined, and make the choice of the parcel they like best. The noise and clamor with which this is attended, and the eagerness visible in the countenances of the buyers, serve not a little to increase the apprehensions of the terrified Africans, who may well be supposed to consider them as the ministers of that destruction to which they think themselves devoted. In this manner, without scruple, are relations and friends separated, most of them never to see each other again. I remember in the vessel in which I was brought over, in the men’s apartment, there were several brothers, who, in the sale, were sold in different lots; and it was very moving on this occasion to see and hear their cries at parting.

O, ye nominal Christians! might not an African ask you, learned you this from your God, who says unto you, Do unto all men as you would men should do unto you? Is it not enough that we are torn from our country and friends to toil for your luxury and lust for gain? Must every tender feeling be likewise sacrificed to your avarice? Are the dearest friends and relations, now rendered dearer by their separation from their kindred, still to be parted from each other, and thus prevented from cheering the gloom of slavery with the small comfort of being together and mingling their sufferings and sorrows? Why are parents to lose their children, brothers their sisters, or husbands their wives? Surely this is a new refinement in cruelty, which, while it has no advantage to atone for it, thus aggravates distress, and adds fresh horrors even to the wretchedness of slavery.

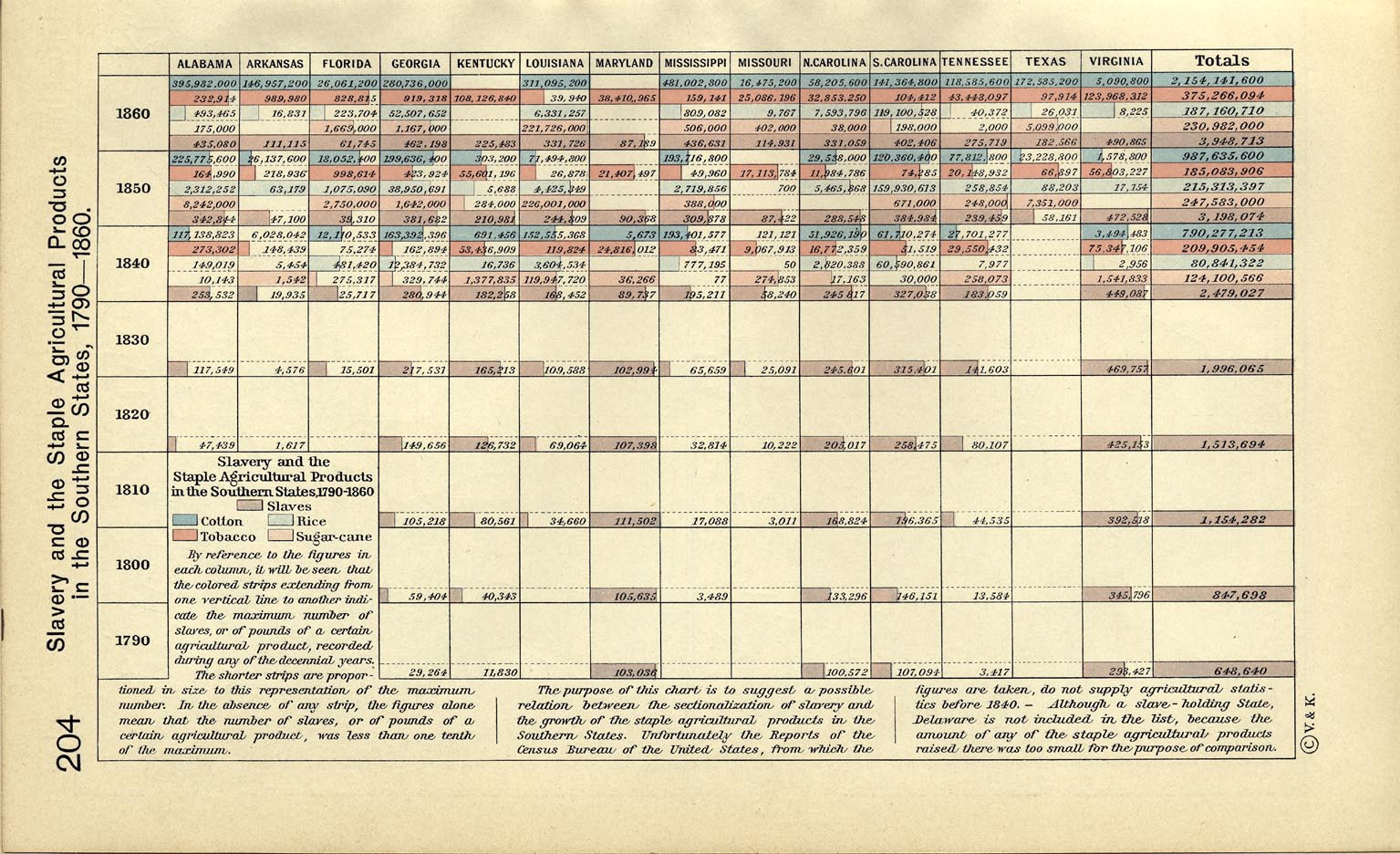

Slavery and the Staple Agricultural Products in the Southern States, 1790-1860

This table uses US Census Beureau data to show the number of slaves in several of the slave-holding states of the US and the breakdown of their use in the production of cotton, tobacco, rice, or sugar-cane. Note that the majority of this data comes from after Britain abolished the Slave Trade in 1807.

Questions for Discussion

The Life of Olaudah Equiano

- What do Equiano’s memories of the treatment of slaves on the ship tell you about the danger of the passage to Barbados and the value of the slaves to the traders?

- What does the end of this excerpt show you about the way abolitionists made their case against slavery? How were they attempting to persuade people that they were correct in calling for an end to the slave trade and slaveholding?

Slavery and Staple Agricultural Products Table

- What does this document reveal about the kinds of products produced by slaves in the United States at this time?

- Knowing that Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807, and that the British slave traders were the original source of the majority of US-held slaves, does anything about this document surprise you?

Cultural Effect of New Commodities in Europe: Coffehouses

One of the effects of international trade was the introduction of new products, first to the wealthy elite, and then to less-wealthy European consumers as the volume of goods circulating brought prices down. Commodities such as coffee, tea, tobacco, cotton, and chocolate, often produced with slave labor in European colonies, didn’t just add new foods and beverages to European diets or new cloth for their clothes, they also influenced behavior. The consumption of tea created a demand for porcelain tea sets which drove the creation of a new industry producing what became known as fine china. The consumption of coffee fueled the creation of a new type of business – the coffeehouse. The following descriptions show both their popularity and the suspicions they aroused.

Excerpts from The Character of a Coffee-House, with Symptoms of a Town-Wit

A Coffee-House is a Lay-Conventicle, Good-fellowship turn’d Puritan, Ill-husbandry in Masquerade, whither people come, after Toping all day, to purchase, at the expence of their last peny, the repute of sober Companions; a Rota-Room that (like Noahs Ark) receives Animals of every sort, from the precise diminutive Band, to the Hectoring Cravat and Cuffs in Folio; a Nursery for train∣ing up the smaller Fry of Virtuosi in confident Tattling, or a Cabal of Kittling Criticks that have only learn’t to Spit and Mew; a Mint of Intelligence, that to make each man his peny-worth, draws out into petty parcels, what the Merchant receives in Builion: He that comes often saves two pence a week in Gazets, and has his News and his Coffee for the same charge, as at a three peny Ordinary they give in Broth to your Chop of Mutton; ’tis an Exchange where Haberdashers of Political small wares meet, and mutually abuse each other, and the Publique, with bottomless stories, and headless notions; the Rendezvous of idle Pamphlets, and persons more idly imployd to read them; a High Court of Justice, where every little Fellow in a Chamlet-Cloak takes upon him to transpose Affairs both in Church and State, to shew reasons against Acts of Parliament, and condemn the Decrees of General Councels.

. . .

The Room stinks of Tobacco, worse than Hell of Brimstone, and is as full of smoaks their Heads that frequent it, whose humours are as various as those of Bedlam, and their discourse oft-times as Heathenish and dull as their Liquor; that Liquor, which by its looks and taste, you may reasonably guess to be Pluto‘s Diet-drink; that Witches tipple out of dead mens Skulls, when they ratifie to Belzebub their Sacramental Vows.

. . .

As you have a hodge-podge of Drinks, such too is your Company, for each man seems a Leveller, and ranks and files himself as he lists, without regard to degrees or order; so that oft you may see a silly Fop, and a worshipful Justice, a griping Rock, and a grave Citizen, a worthy Lawyer, and an errant Pickpocket, a Reverend Nonconformist, and a Canting Mountebank; all blended together, to compose an Oglio of Impertinence.

Exceprts from Coffee-Houses Vindicated in Answer to the late Published Character of a Coffee-House

Wit of late is grown so wanton, and the humour of Affecting it, become so common, that each little Fop whose spungy Brain can but coyn a small drossy Ioque, or two, presently thinks himself priviledg’d to Asperse every Thing that comes in his way though in itself never so Innocent, or beneficial to the Publick; To the Influence of this predominant Folly, we may not improperly refer the Production of those swarms of Insect Pamphlets which the Press weekly spawns into the World, and particularly the Nativity of that Folio-Impertinence which occasions our present Reflections; A Peice whose flanting Title raised our thoughts to an expectation of somewhat extraordinary; But finding little in it but down-right Abuse, The Quintessence of Billingsgate Rhetorick Dreggs of Canting, and such Rubbish Language, as Bubbling, Bully-Rock., Fluxing, Gonorrhea, &c. Charity itself could not but suspect the Authour more conversant somewhere else then in Coffee-houses, and conclude those places being too Civil for a debaucht Humour, had given occasion for his exposing them As Lay-Conventicles, &c.

However we shall preserve that equal regard to Solomons double-fac’d advice, To Answer and not Answer such as our characterizing Authour, That we shall decline Retorting any thing par∣ticularly to his scurrilities; Let the Town-witt (whom we leave to take his own satisfaction) Fence with him if he please at those Weapons; a formall Answer would be too great an Indul∣gence to his Vanity, and make him think too considerably of himself; Besides to reply in the pit∣tyful stile of his pedling Drollery is to ingage in a Game at Push-pin, And to say any thing serious will be no more (to borrow his Phrase) than reading a Lecture to a Monkey; Instead therefore of wasting our own or the Readers time so Impertinently, We shall briefly endeavour to give you an Account of the Vse and Vertues of Coffee, and next consider some of those many conveniences Coffee-houses afford us both for business and conversation.

. . .

Experience proves; That there is nothing more effectual than this reviving Drink to restore their senses that have Brutified themselves by immoderate Tipling heady Liquors which it performs by its exsiccant property before-mentioned, that instantly dries up that cloud of giddy Fumes which boyling up from the over-charged Stomach, oppress the Brain; But this being only a kindness to voluntary Divels (as my Lord Cook calls common Drunkards) we should scarce reckon amongst Coffe’s virtues did it not evidence its quality and shew how beneficial it may prove by parity of Reason, when designed to more worthy and noble uses, Such as expelling Wind, fortifying the Liver, refreshing the Heart, Corroborating the Spirits, both Vital and Animal, quickning the Appetite, assisting Digestion, helping the Stone, taking away Rheums and Defluxions, with a thou∣sand other kindnesses to Nature, which we might Enumerate, did we not think it a sufficient Ar∣gument of its Excellency only to observe, How Vniversally it takes in the World, For we cannot without an Affront to our Nature imagine mankind so sottish As greedily to entertain a Drink that has nothing of sweetness to recommend it to the Gust, nor any of those pleasant blandishments wherewith Wine and other Liquors tempt and debauch our Palates, unless there were some more then ordinary vertue and efficacy in it, yet we see without any of these insinuating advantages, Coffee has so generally, prevail’d that Bread it self (though commonly with us voted the staff of Life) Is scarce of so universal use, For of that the Tartars and Arabians vast and numerous people Eat little or none, whereas both they and the Turks, Persians and almost all the Eastern World are so devoted to Coffee, that besides Innumerable Publick houses for sale of it, There is scarce a private Fire without it all day long; As any that are but moderately acquainted with Shashes and Tur∣bants can witness, Is it not enough to silence the Barking of our Little Wits against this Innocent and wholesome Drink That is so generally used by so many mighty Nations, and those too cele∣brated for the most witty and Sagavious.

. . .

But our Pamphlet-monger (that sputters out senceless Characters faster than any Hocus can vo∣mit Inckle) will needs take upon him to be dictator of all Society, and confine company to sit as mute in a Coffee-house As a Quaker at a silent meeting, or himself with a little Wench when be∣hind the Hangings they are playing a Game at Whist, To this purpose he babbles mightily against Tatling, and makes a great deal of cold mirth with three or four stale Humours that you may find a thousand times better described in a hundred old Plays, yet to collect those excellent obser∣vables cost the poor Soul above half a years time in painful Pilgrimage from one Coffee-house to a∣nother, where planting himself in a dark corner with the dexterity of short-hand he recorded these choice Remarks, whilst all the Town took him for an Excise-man counting the number of dishes; the World is now obliged with the fruits of his Industry, which proves no more then that some giddy-headed Coxcombs like himself (whose S••lls instead of Brains are stuft with Saw-dust) do sometimes intrude into Coffee-houses, A doctrine we are easily perswaded to believe, For if their doors had been kept shut against all Fops ’tis more than probable Himself had never known so much of their Humours, We confess In multiloquio non deest vanitas amongst so much Talk there may happen some to very little purpose, But as we doubt not but the Royal Proclamation has had the good success to prevent for the future any dangerous Intelligence sawcy prying into Arcana Imperij or Irrevent reflections on Affairs of State, so for the little Innocent Extravagancies we hold them very divertising, Every Fool being a Fiddle to the Company, for how else should our Author have raised so much laughter through the town? Besides how infinitely are the vain pra∣tings of these ridiculous pragmatics over-balanced by the sage and solid Reasonings Here frequently to be heard of Experienced Gentlemen, Judicious Lawyers, able Physitians, Ingenious Merchants, and understanding Citizens, In the abstrusest points of Reason, Philosophy, Law and public Commerce?

In brief ’tis undeniable That as you have here the most civil so ’tis generally the most Intelligent Society, The frequenting whose Converse, and observing their Discourses and Department cannot but civilize our manners, enlarge our understandings, refine our Language, teach us a generous confidence and handsome Mode of Address; And brush off that Pudor Subrusticus (As I remember Tully somewhere calls it) That clownish kind of modesty, frequently incident to the best Natures, which renders them Sheepish and Ridiculous in company.

So that upon the whole matter, spight of the idle Sarcasms and paltry reproaches thrown upon it, we may with no less truth than plainness give this brief Character of a well regulated Coffee-house (for our Pen disdains to be Advocate for any sordid holes that assume that Name to cloak the Practice of Debauchery) That it is:

- The Sanctuary of Health.

- The Nursery of Temperance.

- The Delight of Frugality.

- An Accademy of Civility – AND –

- Free-School of Ingenuity.

Questions for Discussion

- What were the criticisms of coffee-houses made in The Character of a Coffee-House? What examples did the author give that showed the reasons for his dislike?

- How did the author of Coffee-Houese Vindicated rebut those criticisms? What reasons did he give for his more positive views?

- Who do you think would be persuaded by each piece and why?

Additional Resources:

Dr. Kimberly Kutz Elliott, “The problem of picturing slavery,” in Smarthistory, March 2, 2022, accessed January 22, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/seeing-america-2/civil-war-in-art/causes-problem-of-picturing-slavery/.

“How Did the Slave Trade End in Britain?” Royal Museums Greenwich, 2023. This web site includes an interesting video clip about Equiano as well as a look at documentation of the slave trade held by the Royal Museums Greenwich. https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/how-did-slave-trade-end-britain#:~:text=Three%20years%20later%2C%20on%2025,people%20in%20the%20British%20Empire.&text=Today%2C%2023%20August%20is%20known,Slave%20Trade%20and%20its%20Abolition.

“Abolition of the Slave Trade in Britain,” by John Oldfield, British Library, 2021. https://www.bl.uk/restoration-18th-century-literature/articles/abolition-of-the-slave-trade-and-slavery-in-britain