The Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries was an era of transformation in which individual scientific fields such as mathematics, chemistry, or astronomy began to emerge as independent from other disciplines such as philosophy or theology. The development of the scientific method, as well as advances in specific fields of knowledge, began to change the way humans thought about nature, society, and their relationship to both.

Looking at the world anew

In scientific discovery there is always a tension between holding on to knowledge and understanding that has been established and recognized by the scientific community and forging new explanations when new data allows. This tension existed from the beginning, as the following excerpts from Bacon’s Aphorisms and

Sir Francis Bacon – excerpts from Aphorisms Book I

I. Man, as the minister and interpreter of nature, does and understands as much as his observations on the order of nature, either with regard to things or the mind, permit him, and neither knows nor is capable of more.

III. Knowledge and human power are synonymous, since the ignorance of the cause frustrates the effect; for nature is only subdued by submission, and that which in contemplative philosophy corresponds with the cause in practical science becomes the rule.

V. Those who become practically versed in nature are, the mechanic, the mathematician, the physician, the alchemist, and the magician, but all (as matters now stand) with faint efforts and meager success.

VI. It would be madness and inconsistency to suppose that things which have never yet been performed can be performed without employing some hitherto untried means.

VIII. Even the effects already discovered are due to chance and experiment rather than to the sciences; for our present sciences are nothing more than peculiar arrangements of matters already discovered, and not methods for discovery or plans for new operations.

IX. The sole cause and root of almost every defect in the sciences is this, that while we falsely admire and extol the powers of the human mind, we do not search for its real helps.

X. The subtilty of nature is far beyond that of sense or of the understanding: so that the specious meditations, speculations, and theories of mankind are but a kind of insanity, only there is no one to stand by and observe it.

XI. As the present sciences are useless for the discovery of effects, so the present system of logic is useless for the discovery of the sciences.

XII. The present system of logic rather assists in confirming and rendering inveterate the errors founded on vulgar notions than in searching after truth, and is therefore more hurtful than useful.

XIX. There are and can exist but two ways of investigating and discovering truth. The one hurries on rapidly from the senses and particulars to the most general axioms, and from them, as principles and their supposed indisputable truth, derives and discovers the intermediate axioms. This is the way now in use. The other constructs its axioms from the senses and particulars, by ascending continually and gradually, till it finally arrives at the most general axioms, which is the true but unattempted way.

XXII. Each of these two ways begins from the senses and particulars, and ends in the greatest generalities. But they are immeasurably different; for the one merely touches cursorily the limits of experiment and particulars, while the other runs duly and regularly through them—the one from the very outset lays down some abstract and useless generalities, the other gradually rises to those principles which are really the most common in nature.

XXXVI. We have but one simple method of delivering our sentiments, namely, we must bring men to particulars and their regular series and order, and they must for a while renounce their notions, and begin to form an acquaintance with things.

Sir Francis Bacon – excerpts from Aphorisms Book II

X. The object of our philosophy being thus laid down, we proceed to precepts, in the most clear and regular order. The signs for the interpretation of nature comprehend two divisions; the first regards the eliciting or creating of axioms from experiment, the second the deducing or deriving of new experiments from axioms. The first admits of three subdivisions into ministrations. 1. To the senses. 2. To the memory. 3. To the mind or reason.

For we must first prepare as a foundation for the whole, a complete and accurate natural and experimental history. We must not imagine or invent, but discover the acts and properties of nature.

But natural and experimental history is so varied and diffuse, that it confounds and distracts the understanding unless it be fixed and exhibited in due order. We must, therefore, form tables and co-ordinations of instances, upon such a plan, and in such order that the understanding may be enabled to act upon them.

Even when this is done, the understanding, left to itself and to its own operation, is incompetent and unfit to construct its axioms without direction and support. Our third ministration, therefore, must be true and legitimate induction, the very key of interpretation. We must begin, however, at the end, and go back again to the others.

Excerpts from Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius or Starry Messenger

Introduction

In the present small treatise, I set forth some matters of great interest for all observers of natural phenomena to look at and consider. They are of great interest, I think, first, from their intrinsic excellence; secondly, from their absolute novelty; and lastly, also on account of the instrument by the aid of which they have been presented to my apprehension.

The number of the Fixed Stars which observers have been able to see without artificial powers of sight up to this day can be counted. It is therefore decidedly a great feat to add to their number, and to set distinctly before the eyes other stars in myriads, which have never been seen before, and which surpass the old, previously known, stars in number more than ten times.

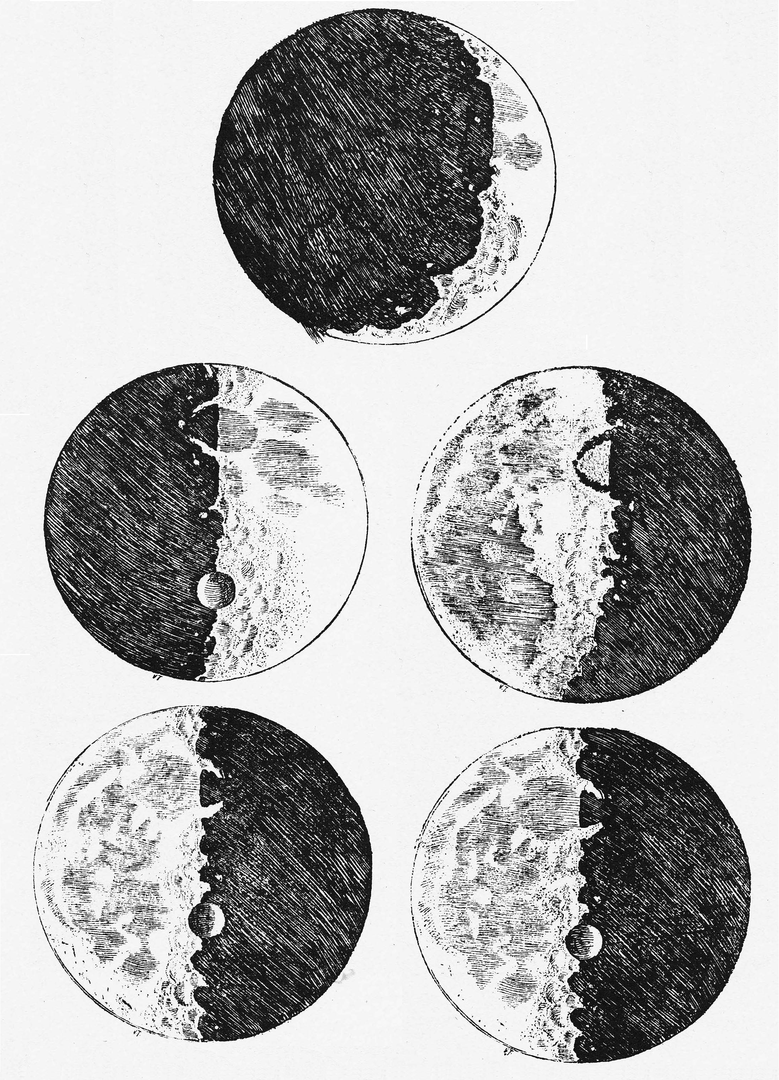

Again, it is a most beautiful and delightful sight to behold the body of the Moon, which is distant from us nearly sixty semi-diameters of the Earth, as near as if it was at a distance of only two of the same measures; so that the diameter of this same Moon appears about thirty times larger, its surface about nine hundred times, and its solid mass nearly 27,000 times larger than when it is viewed only with the naked eye; and consequently anyone may know with the certainty that is due to the use of our senses, that the Moon certainly does not possess a smooth and polished surface, but one rough and uneven, and, just like the face of the Earth itself, is everywhere full of vast protuberances, deep chasms, and sinuosities.

Then to have got rid of disputes about the Galaxy or Milky Way, and to have made its nature clear to the very senses, not to say to the understanding, seems by no means a matter which ought to be considered of slight importance. In addition to this, to point out, as with one’s finger, the nature of those stars which every one of the astronomers up to this time has called nebulous, and to demonstrate that it is very different from what has hitherto been believed, will be pleasant, and very fine. But that which will excite the greatest astonishment by far, and which indeed especially moved me to call the attention of all astronomers and philosophers, is this, namely, that I have discovered four planets, neither known nor observed by any one of the astronomers before my time, which have their orbits round a certain bright star, one of those previously known, like Venus and Mercury round the Sun, and are sometimes in front of it, sometimes behind it, though they never depart from it beyond certain limits. All these facts were discovered and observed a few days ago with the help of a telescope devised by me, through God’s grace first enlightening my mind.

Perchance other discoveries still more excellent will be made from time to time by me or by other observers, with the assistance of a similar instrument, so I will first briefly record its shape and preparation, as well as the occasion of its being devised, and then I will give an account of the observations made by me.

Galileo’s account of the invention of his telescope

About ten months ago a report reached my ears that a Dutchman had constructed a telescope, by the aid of which visible objects, although at a great distance from the eye of the observer, were seen distinctly as if near; and some proofs of its most wonderful performances were reported, which some gave credence to, but others contradicted. A few days after, I received confirmation of the report in a letter written from Paris by a noble Frenchman, Jaques Badovere, which finally determined me to give myself up first to inquire into the principle of the telescope, and then to consider the means by which I might compass the invention of a similar instrument, which a little while after I succeeded in doing, through deep study of the theory of Refraction; and I prepared a tube, at first of lead, in the ends of which I fitted two glass lenses, both plane on one side, but on the other side one spherically convex, and the other concave. Then bringing my eye to the concave lens I saw objects satisfactorily large and near, for they appeared one-third of the distance off[11] and nine times larger than when they are seen with the natural eye alone. I shortly afterwards constructed another telescope with more nicety, which magnified objects more than sixty times. At length, by sparing neither labor nor expense, I succeeded in constructing for myself an instrument so superior that objects seen through it appear magnified nearly a thousand times, and more than thirty times nearer than if viewed by the natural powers of sight alone.

Galileo’s first observations with his telescope

It would be altogether a waste of time to enumerate the number and importance of the benefits which this instrument may be expected to confer, when used by land or sea. But without paying attention to its use for terrestrial objects, I betook myself to observations of the heavenly bodies; and first of all, I viewed the Moon as near as if it was scarcely two semi-diameters of the Earth distant. After the Moon, I frequently observed other heavenly bodies, both fixed stars and planets, with incredible delight; and, when I saw their very great number, I began to consider about a method by which I might be able to measure their distances apart, and at length, I found one. And here it is fitting that all who intend to turn their attention to observations of this kind should receive certain cautions. For, in the first place, it is absolutely necessary for them to prepare a most perfect telescope, one which will show very bright objects distinct and free from any mistiness, and will magnify them at least 400 times, for then it will show them as if only one-twentieth of their distance off. For unless the instrument be of such power, it will be in vain to attempt to view all the things which have been seen by me in the heavens, or which will be enumerated hereafter.

But in order that anyone may be a little more certain about the magnifying power of his instrument, he shall fashion two circles, or two square pieces of paper, one of which is 400 times greater than the other, but that will be when the diameter of the greater is twenty times the length of the diameter of the other. Then he shall view from a distance simultaneously both surfaces, fixed on the same wall, the smaller with one eye applied to the telescope, and the larger with the other eye unassisted; for that may be done without inconvenience at one and the same instant with both eyes open. Then both figures will appear of the same size, if the instrument magnifies objects in the desired proportion.

. . .

The Moon

Let me speak first of the surface of the Moon, which is turned towards us. For the sake of being understood more easily, I distinguish two parts in it, which I call respectively the brighter and the darker. The brighter part seems to surround and pervade the whole hemisphere; but the darker part, like a sort of cloud, discolors the Moon’s surface and makes it appear covered with spots. Now these spots, as they are somewhat dark and of considerable size, are plain to everyone, and every age has seen them, wherefore I shall call them great or ancient spots, to distinguish them from other spots, smaller in size, but so thickly scattered that they sprinkle the whole surface of the Moon, but especially the brighter portion of it. These spots have never been observed by anyone before me; and from my observations of them, often repeated, I have been led to that opinion which I have expressed, namely, that I feel sure that the surface of the Moon is not perfectly smooth, free from inequalities and exactly spherical, as a large school of philosophers considers with regard to the Moon and the other heavenly bodies, but that, on the contrary, it is full of inequalities, uneven, full of hollows and protuberances, just like the surface of the Earth itself, which is varied everywhere by lofty mountains and deep valleys.

. . .

The Milky Way

The next object which I have observed is the essence or substance of the Milky Way. By the aid of a telescope, anyone may behold this in a manner which so distinctly appeals to the senses that all the disputes which have tormented philosophers through so many ages are exploded at once by the irrefragable evidence of our eyes, and we are freed from wordy disputes upon this subject, for the Galaxy is nothing else but a mass of innumerable stars planted together in clusters. Upon whatever part of it you direct the telescope straightway a vast crowd of stars presents itself to view; many of them are tolerably large and extremely bright, but the number of small ones is quite beyond determination.

And whereas that milky brightness, like the brightness of a white cloud, is not only to be seen in the Milky Way, but several spots of a similar color shine faintly here and there in the heavens, if you turn the telescope upon any of them you will find a cluster of stars packed close together. Further—and you will be more surprised at this,—the stars which have been called by every one of the astronomers up to this day nebulous, are groups of small stars set thick together in a wonderful way, and although each one of them on account of its smallness, or its immense distance from us, escapes our sight, from the commingling of their rays there arises that brightness which has hitherto been believed to be the denser part of the heavens, able to reflect the rays of the stars or the Sun.

. . .

Jupiter’s satellites

I have now finished my brief account of the observations which I have thus far made with regard to the Moon, the Fixed Stars, and the Galaxy. There remains the matter, which seems to me to deserve to be considered the most important in this work, namely, that I should disclose and publish to the world the occasion of discovering and observing four PLANETS, never seen from the very beginning of the world up to our own times, their positions, and the observations made during the last two months about their movements and their changes of magnitude; and I summon all astronomers to apply themselves to examine and determine their periodic times, which it has not been permitted me to achieve up to this day, owing to the restriction of my time. I give them warning however again, so that they may not approach such an inquiry to no purpose, that they will want a very accurate telescope, and such as I have described at the beginning of this account.

On the 7th day of January in the present year, 1610, in the first hour of the following night, when I was viewing the constellations of the heavens through a telescope, the planet Jupiter presented itself to my view, and as I had prepared for myself a very excellent instrument, I noticed a circumstance which I had never been able to notice before, owing to want of power in my other telescope, namely, that three little stars, small but very bright, were near the planet; and although I believed them to belong to the number of the fixed stars, yet they made me somewhat wonder, because they seemed to be arranged exactly in a straight line, parallel to the ecliptic, and to be brighter than the rest of the stars, equal to them in magnitude. Their position with reference to one another and to Jupiter was as follows.

On the east side, there were two stars, and a single one towards the west. The star which was furthest towards the east, and the western star, appeared rather larger than the third.

I scarcely troubled at all about the distance between them and Jupiter, for, as I have already said, at first I believed them to be fixed stars; but when on January 8th, led by some fatality, I turned again to look at the same part of the heavens, I found a very different state of things, for there were three little stars all west of Jupiter, and nearer together than on the previous night, and they were separated from one another by equal intervals, as the accompanying illustration shows.

At this point, although I had not turned my thoughts at all upon the approximation of the stars to one another, yet my surprise began to be excited, how Jupiter could one day be found to the east of all the aforesaid fixed stars when the day before it had been west of two of them; and forthwith I became afraid lest the planet might have moved differently from the calculation of astronomers, and so had passed those stars by its own proper motion. I, therefore, waited for the next night with the most intense longing, but I was disappointed of my hope, for the sky was covered with clouds in every direction.

But on January 10th the stars appeared in the following position with regard to Jupiter; there were two only, and both on the east side of Jupiter, the third, as I thought, being hidden by the planet. They were situated just as before, exactly in the same straight line with Jupiter, and along the Zodiac.

When I had seen these phenomena, as I knew that corresponding changes of position could not by any means belong to Jupiter, and as, moreover, I perceived that the stars which I saw had been always the same, for there were no others either in front or behind, within a great distance, along the Zodiac,—at length, changing from doubt into surprise, I discovered that the interchange of position which I saw belonged not to Jupiter, but to the stars to which my attention had been drawn, and I thought therefore that they ought to be observed henceforward with more attention and precision.

. . .

Galileo goes on to record his observations for over two months, providing details of the location of the “stars” that he comes to determine are actually satellites of Jupiter, or as he later says, “planets.”

. . .

These determinations of the motion of Jupiter and the adjacent planets (his satellites) by reference to a fixed star, I have thought well to present to the notice of astronomers, in order that anyone may be able to understand from them that the movements of these planets (Jupiter’s satellites) both in longitude and in latitude agree exactly with the motions [of Jupiter] which are extracted from tables.

These are my observations upon the four Medicean planets, recently discovered for the first time by me; and although it is not yet permitted me to deduce by calculation from these observations the orbits of these bodies, yet I may be allowed to make some statements, based upon them, well worthy of attention.

Deductions from the previous observations

And, in the first place, since they are sometimes behind, sometimes before Jupiter, at like distances, and withdraw from this planet towards the east and towards the west only within very narrow limits of divergence, and since they accompany this planet alike when its motion is retrograde and direct, it can be a matter of doubt to no one that they perform their revolutions about this planet, while at the same time, they all accomplish together orbits of twelve years’ length about the center of the world. Moreover, they revolve in unequal circles, which is evidently the conclusion to be drawn from the fact that I have never been permitted to see two satellites in conjunction when their distance from Jupiter was great, whereas near Jupiter two, three, and sometimes all (four), have been found closely packed together. Moreover, it may be detected that the revolutions of the satellites which describe the smallest circles round Jupiter are the most rapid, for the satellites nearest to Jupiter are often to be seen in the east, when the day before they have appeared in the west, and contrariwise. Also, the satellite moving in the greatest orbit seems to me, after carefully weighing the occasions of its returning to positions previously noticed, to have a periodic time of half a month. Besides, we have a notable and splendid argument to remove the scruples of those who can tolerate the revolution of the planets round the Sun in the Copernican system, yet are so disturbed by the motion of one Moon about the Earth, while both accomplish an orbit of a year’s length about the Sun, that they consider that this theory of the constitution of the universe must be upset as impossible; for now we have not one planet only revolving about another, while both traverse a vast orbit about the Sun, but our sense of sight presents to us four satellites circling about Jupiter, like the Moon about the Earth, while the whole system travels over a mighty orbit about the Sun in the space of twelve years.

Images

Frederick R. Barndard is reportedly the first to use the famous phrase, “a picture paints a thousand words” or “a picture is worth a thousand words.” He was talking about the ability of graphics telling a story as well as a large amount of text. The following two images may be an example of this. The first was added to Galileo Galilei’s work titled Opere di Galileo Galilei printed in Bologna in the 1650s. The image shows Galileo offering his telescope, an instrument he is often credited with inventing, to allegorical figures, or perhaps a Greek goddess and her companions.

This second image is taken from Galileo’s Sederius Nuncius or Starry Messenger. These are drawings of the moon which Galileo made to record his observations using the telescope.

Questions for Discussion

- According to Sir Francis Bacon, what are the problems with the way humans have attempted to gain scientific knowledge up to his own time? What does he propose to do differently?

- Does Galileo seem to be giving directions to others as to how to see the same things he has observed with his telescope? Why would this be important?

- How does Galileo present his argument for his interpretation of what he has observed?

- Compare and contrast the two images above. What does each one tell us about the advancement of astronomy in this period, who this information would appeal to, and how it was conveyed?

Additional Resources

The Scientific Revolution: Crash Course History of Science #12 This Crash Course video explores how and why historians usually choose Copernicus and Galileo as the starting point of the Scientific Revolution, at least in terms of astronomy, though there were scholars before them who also looked at many of the same concepts. https://youtu.be/vzo8vnxSARg

Galileo’s World – An Exhibit without Walls University Libraries, University of Oklahoma. This site includes text, photos, and short videos documenting the story of Galileo and his times, emphasizing the “interconnectedness of human achievement.” https://galileo.ou.edu/exhibits

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, March 1665. This page links to the first publication of the Royal Society and indicates the wide range of the Royal Society’s early work. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/toc/rstl/1/1

World’s Oldest Science Journal – Objectivity 17. This video from the YouTube Objectivity series is a discussion of the first issue of Philosophical Transactions with Sir Paul Nurse who was President of the Royal Society in 2016 and Brady Haran, Objectivity’s creator, and presenter. https://youtu.be/QE0DCaw7EDY