18.1 Introduction

The term “genocide” was adopted in the immediate aftermath of World War II out of the need to designate, to name, the most horrendous crime perpetrated by the Nazi regime: the systematic, state-run murder of the European Jews. The word itself means “murder of a people,” and while the act of genocide was not invented in the twentieth century – forms of genocide have occurred since the ancient world – never before had a government carried out a genocide that was as far-reaching, as bureaucratically-managed, or as focused as the Holocaust. While much of the Holocaust took the form of blood-soaked massacres, akin to the slaughter of the Armenians by the inchoate state of Turkey in the early 1920s or the various mass killings of Native Americans in the long, bloody colonization of the Americas by Europeans, the Holocaust was also distinct from other genocides in that much of it was industrialized: run on timetables, with the killing occurring in gas chambers built by Nazi agents or private firms contracted to do the work. In short, the Holocaust was a distinctly and horrifyingly modern genocide.

World War II would “just” be the story of a horrendously costly war if not for the Holocaust. The term itself refers to early Jewish rituals of sacrifice by fire, in which offerings were made to God and burned in the ancient Temple of Solomon (long since destroyed by the Romans) in Jerusalem. Today, the term is mostly used in the United States; the rest of the world largely uses the term Shoah, which means “catastrophe” in Hebrew. Its core definition is simple: the ideologically-motivated, brutal murder of approximately 6,000,000 Jews by the Nazi regime, representing two-thirds of Europe’s Jewish population at the time, and one-third of the entire global Jewish population. Thus, in addition to its modern character, the Holocaust stands out among the history of genocides for its shocking “success” from the perspective of the Nazi leadership: they set out to kill every Jew, theoretically in the entire world, and were horrifyingly successful at doing so in a very short time period.

In addition to the murder of the Jews, millions more were killed by the Nazis in the name of their ideology. While estimates vary, at least 250,000 Romani (“Gypsies”) were murdered. At least 6,000 male homosexuals were murdered. Many thousands of ideological “enemies,” from Jehovah’s Witnesses to various kinds of political leftists, were murdered as well. In addition, while not normally considered part of the Holocaust per se, almost 20,000,000 civilians in the Slavic nations – Poles and Russians especially – were murdered by the Nazis in large part because of Nazi racial ideology. Slavs too were “racial inferiors” and “subhumans” according to the Nazi racial hierarchy, and thus civilian populations in the Slavic countries were either killed outright or subjected to treatment tantamount to murder. Thus, while the Holocaust is, and must be, defined primarily as the genocide of the European Jews by the Nazis, it is still appropriate to consider the other victims of Nazi ideology as an aspect of Nazi mass murder as a whole.

Terms for Identification

- Genocide

- Nuremberg Laws

- Kristallnacht

- Ghettos

- Concentration Camps

- Nuremberg Trials

18.2 Before the Holocaust

The Nazis implemented anti-Jewish racial laws, known as the Nuremberg Laws, in 1935. Those laws defined “full” Jews as having three or four practicing Jews as grandparents, and those with two or one as being distinct categories of “mixed” (Mischlinge) Jews, the latter of whom received some exemptions from anti-Semitic laws. Jews were deprived of their citizenship and banned from various professions. For the next four years leading up to the war, the goal of the Nazi government was to force Jews to emigrate from the Reich, while extracting as much wealth from them as possible. The state imposed a “Reich Flight Tax,” meant to fleece fleeing Jews of as much of their wealth as possible, and in 1938, the Nazis forced all Jews to register their property, which was then expropriated in a campaign dubbed “Aryanization.”

Antisemetic Acts Before the War

March 1933 = Nazis open Dachau concentration camp, soon to be followed by others

April 1933 – Boycott of Jewish businesses

July 1933 – Law strips Jewish immigrants from Eastern European of their German citizenship

May 1935 – Jews banned from serving in the German military

September 1935 – Nuremberg Laws enacted, Jews no longer considered German citizens

March 1938 Anschulss, all antisemitic decrees applied to Austria after invasion

August 1938 – Italy enacts antisemitic laws

November 1938 – Kristallnacht

In November of 1938 the Nazis initiated a nationwide pogrom known as the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht) in which some 90 Jews were killed and 177 synagogues burned to the ground, after which 20,000 Jewish men were arrested for “disrupting the peace” and incarcerated in prison camps – this represented the first mass roundup of Jews simply for being Jewish. Hermann Göring, at the time the second most powerful Nazi leader after Hitler, then demanded one billion Marks from the German Jewish population for the damage caused by the riots. After Kristallnacht, many of the remaining German Jews desperately sought asylum outside of Germany, but were all too often rebuffed by countries which, in the midst of the Great Depression, allowed in only a trickle of immigrants each year (Jewish or otherwise). Approximately half of the 500,000 German Jews did manage to flee before the war despite the incredible difficulty of doing so at the time.

Simultaneously, high-ranking Nazi officials in the SS were exploring permanent options for ridding the Reich of Jews. Serious thought and research went into plans to create Jewish “reservations” in Poland as well as a plan to ship all of the Jews in German-held territory to the African island of Madagascar. Even after large-scale murder campaigns in Eastern Europe began in 1941, many Nazis were still looking for some way to transport and dump the Jews of Europe somewhere far from Germany. The stated goal of these schemes was to render the entire face of Europe, and possibly the world, Judenrein: “Jew-Free.” In the end, the “final solution to the Jewish question” – the Nazi’s euphemism for the Holocaust – was decided to consist not of deportation, but of systematic murder, but that decision does not appear to have been reached until 1941.

The irony of considering the case of German (and, as of 1938, Austrian) Jews in detail is that the large majority of the victims of the Holocaust were not from Germany. The bulk of the Jewish population of Europe was in the east, concentrated in Poland, Russia, and the Ukraine. Poland alone had a Jewish population of approximately 3,000,000, 10% of the population of Poland as a whole. Unlike the Jews of Central and Western Europe, most of the Jews of Eastern Europe were largely unassimilated, living in separate communities, speaking Yiddish as their vernacular language instead of Polish or Russian, and often facing harsh anti-Semitism from their non-Jewish neighbors (which was somewhat muted in the nominally unprejudiced Soviet Union). Thus, the Jews of the east had almost nowhere to run and few who would help them once the German war machine arrived.

When the war began, even Polish Jews were not systematically murdered right away: they were beaten, humiliated, and sometimes murdered outright, but there was not yet a campaign of focused, organized murder against them. Instead, the initial task of Nazi murder squads was the elimination of the Polish “leadership class,” which came to mean intellectuals, politicians, communists, and Catholic priests. At least 50,000 Polish social, political, and intellectual elites were murdered by SS death squads or regular German soldiers in a campaign codenamed “Operation Tannenberg.”

On encountering the enormous numbers of Jews in Poland, the Nazis opted to drive them into hastily-constructed ghettos in towns and cities. Ghettos were neighborhoods of a town or city that were usually fenced-off, surrounded with barbed wire, and then filled with the Jews of the surrounding areas. The ghettos were built almost immediately, from late 1939 to early 1940, and ended up housing millions of people in areas that were meant to hold perhaps a few hundred thousand at most. The largest were in the large Polish cities of Warsaw and Lodz; the Warsaw Ghetto alone housed over 400,000 Jews at its height in late 1941. Conditions were atrocious: the official food ration “paid” to Jewish workers who worked as slave laborers for the Nazi war effort consisted of about 600 – 800 calories a day (an adult should consume about 2,000 a day to remain healthy). Potato peels were “as precious as diamonds” to ghetto inhabitants. The ghettos alone ended up costing the lives of approximately 500,000 people from starvation and disease.

18.3 The Holocaust Begins

The Holocaust itself began with the invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941. As German armies advanced into Soviet territory, they were followed by four teams of Einsatzgruppen – mobile killing squads – charged with killing “Jews, Gypsies, and the disabled.” The Einsatzgruppen’s technique for murdering their victims consisted of marching Jews into the woods or fields and systematically shooting them. The victims would be forced to dig mass graves or ditches, to strip, and to watch as their entire community was slaughtered. Mothers would be forced to strip, then undress their children, watch their children be murdered, and then join them in the mass graves. The Einsatzgruppen and the local helpers they recruited were responsible for approximately 1 million deaths over the course of the war. The Einsatzgruppen were aided by regular Wehrmacht (German army) units and by battalions of the Order Police, a hybrid of police force and national guard mobilized for the war effort. In other words, many “regular soldiers,” not just Nazi party members, were responsible for killing innocent men, women, and children, often for days at a time and at point-blank range. This aspect of the Holocaust is today referred to as the “Holocaust by bullets,” one that was largely overlooked by historians for many decades after the war.

There were various logistical problems with this technique, however. It was hard to generalize it in urban areas already under Nazi control. Many members of the Einsatzgruppen suffered from mental breakdowns from murdering innocent people day after day. There were never very many Einsatzgruppen to begin with: four teams with about 6,000 soldiers assigned to them in total. Out of necessity, they made heavy use of auxiliary troops to do much of the actual shooting, recruited from Ukrainian, Latvian, Lithuanian, or Estonian POW camps. These auxiliaries were called “Hiwis,” an abbreviation of Hilfswilligen (“helpers”), by the Nazis. Soon, both members of the SS’s army, the Waffen SS, as well as regular soldiers of the Wehrmacht were assigned to “Jewish Actions,” the euphemism for organized massacres.

At some point between the late summer and fall of 1941, the top Nazi leadership decided to abandon earlier experiments with forced deportations and to search instead for more efficient methods of murder. Almost immediately after the implementation of the Einsatzgruppen, the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, ordered experiments with better means of mass murder, which resulted in Nazi technicians devising “gas vans” that killed their victims through carbon monoxide poisoning. By late fall of 1941, killing facilities were being built in the concentration camps of Majdanek and Auschwitz, both of which had been built as slave labor camps in 1940. There, the first experiments with the infamous pesticide Zyklon B were carried out on Russian POWs.

The Holocaust

September 1939 – Directive to establish ghettos in German-occupied Poland

1941 – Numerous attacks on Jews led by fascists throughout Europe

1942 – Deportation of Jews to “killing centers”

1943 – Orders for the “liquidation” of ghettos

Mid-1944 – Hungarian Jews deported to Auschwitz

July 1944 – Soviets liberate Majdanek killing center

January 1945 – Soviets liberate Auschwitz

April 1945 – US Forces liberate Buchenwald

April 1945 – British forces liberated Bergen-Belsen and other camps in Northern Germany

18.4 The Peak Killing Period

Based on the experiments with gas vans and temporary gas chambers at Auschwitz, SS leaders concluded that stationary killing centers would be the most efficient and (for the killers) psychologically viable form of mass murder. Thus, as of early 1942, the Nazis embarked on the most notorious project of the Holocaust: the creation of the extermination camps. Extermination camps were not the same thing as concentration camps. Concentration camps were prison camps, some of which created during the first weeks of Nazi rule in 1933. There were literally tens of thousands of concentration camps of various kinds scattered across the entire breadth of German-controlled territory. Extermination camps, however, were designed for one purpose: to kill people. There were only six of them in total, and most were very small – often about a quarter of a square mile in size. All were located in occupied Poland, near rail lines and hidden in forests away from major population centers. They were not meant to house prisoners for slave labor; new arrivals to an extermination camp were typically dead within two hours. They were, in short, “death factories,” production facilities of murder that ran on industrial timetables.

The height of the Holocaust was thus shockingly short. It lasted from early 1942, when the extermination facilities were put into operation, until the late summer of 1943, a period of just over a year that saw 50% of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust itself murdered. The major reason for that incredible speed is that the ghettos of Poland were emptied into the extermination camps. The extermination camp Treblinka alone killed at least 800,000 people, most of whom were sent from the enormous ghetto of Warsaw. The millions of Jews who had been in Poland and the Russian territories of the west were murdered at a stunning, completely unprecedented rate.

The most infamous of the camps is unquestionably Auschwitz. Auschwitz was a great exception among the extermination camps in that it did house Jewish prisoners who were not immediately killed. Instead, about 80% of new arrivals to Auschwitz were sent immediately to their deaths in the gas chambers, while the other 20% were temporarily enslaved. More is known about day-to-day life inside of a death camp from Auschwitz because a relatively large number of its victims survived the war, although “relative” in this case still means “far less than 1%.” Likewise, the infamous tattoos issued to prisoners were only performed at Auschwitz; there was no point in tattooing victims who were to be killed within hours, after all.

Within Auschwitz, not just Jews but regular criminals, enemies of the Nazi regime, Romani, and various other groups were housed in grossly overcrowded barracks. These prisoners were treated differently by German and auxiliary guards based on who they were and where they were from, and they were actively encouraged to treat each other differently based on those distinctions as well. Non-Jewish German criminals were given important positions as kapos, team leaders, who oversaw Jewish slaves in the construction of new buildings in the vast, sprawling Auschwitz camp complex (it was over 20 kilometers across, including numerous sub-camps) or working in factories designed to support the German war effort. Of the approximately 200,000 Jews who were spared immediate murder on arrival, the large majority were either worked to death or murdered in the gas chambers after becoming too weak to work.

The five death camps besides Auschwitz operated from early 1942 until the fall or winter of 1943 (one, Madjanek, was operational until the summer of 1944). They were used primarily to murder the Jews of Poland and their total death toll was close to 2 million victims. In turn, they were never meant to be permanent: there were no large-scale slave labor facilities and only a handful of Jews were kept alive on arrival to work as slaves for the guards and to burn the bodies of their fellow victims after they were gassed (the survival rate from the three major camps besides Auschwitz was one one-thousandth of 1%, or .0001 to 1, representing the 150 people who survived and the 1.5 million who did not). Slave revolts occurred at two camps in August and October of 1943, which explains the fact that anyone survived these camps, but by then the camps had already succeeded: almost the entire Polish Jewish population was dead, starved in the ghettos or gassed in the camps. Afterwards, the SS destroyed the remains of the camps to hide the evidence of what had happened there.

Auschwitz, however, had been built to be permanent. Its gas chambers were large and made of concrete and steel (unlike the wood sheds used to murder in the other extermination camps). It was intended to be the final destination for every Jew captured by the Nazis in the years to come, and thus most Jews from the western European countries occupied by Germany were sent to die in Auschwitz. The Nazis continued to prioritize the “final solution” even as the war turned against them, shipping hundreds of thousands to Auschwitz as the Allies steadily pressed against them in the east and south.

One of the most bizarre and chilling episodes of the Holocaust was the Nazi takeover of Hungary in mid-1944. There, in what had been a staunch German ally, over 700,000 Jews had survived the war, “protected” in the sense that the Hungarian government had resisted the demands of the Germans to turn over its Jews for murder. When the Germans learned that the Hungarians were negotiating with the Soviets to switch allegiances, now that the German defeat was all but assured by early 1944, they supported a coup by Hungarian fascists under the direction of the Nazi state. That summer, at an astonishing rate, SS specialists overseeing Hungarian fascist police deported over 500,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz. The vast majority were killed on arrival; in the Fall of 1944 Auschwitz was operated at its maximum capacity of killing up to 12,000 people a day. It bears emphasizing that the Holocaust was regarded by the top Nazi leadership as being a priority that was at least as high as actually fighting the war. Even after the war was evidently lost, tremendous efforts were made to kill every Jew then in German hands.

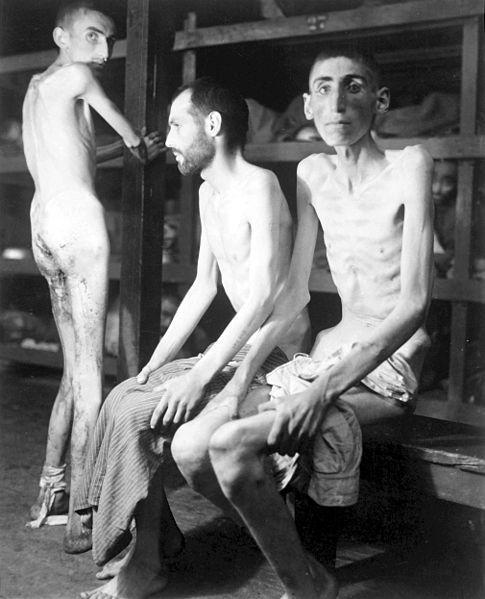

In early 1945, as the Soviet army closed from the east and the western Allies from the west, the Nazis initiated a series of death marches from the camps in Poland. Jewish prisoners that had survived up to that point, against incredible odds, were forced to march up to twenty miles through the Polish winter, then loaded into cattle cars and shipped into Germany. The western Allies – mostly Britain and the US – discovered the first evidence of the Holocaust when they liberated these German camps, discovering tens of thousands of corpses and thousands of horribly malnourished survivors. Likewise, the Soviet army liberated Auschwitz itself, discovering the gas chambers and the smattering of survivors who had been left behind when the Germans fled. Ultimately, the Holocaust ended because the war ended. The Nazis had been intent on “winning the Holocaust” even after it was self-evident that they could not win the war.

18.5 The Aftermath

The liberation of the camps was horrifying to the Allied soldiers who discovered them in the closing months of the war. Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander of the forces that had carried out the D-Day invasion, ordered that British and American troops alike document what they discovered – the huge mounds of corpses, the open graves, the emaciated survivors, and the gas chambers – lest those horrors be dismissed as “propaganda” at some point in the future. Likewise, Soviet forces preserved the evidence discovered in the eastern camps, including Auschwitz itself. As the war in Europe finally ended, Allied troops and agents immediately embarked on an enormous effort to locate, catalog, and preserve the documentation having to do with the Holocaust in German army, state, and SS offices as they prepared the groundwork for war crimes trials.

The scope of the Holocaust shocked even battle-hardened troops who were already aware of German depredations against civilians. At the the Nuremberg Trials, organized to legally prosecute the Nazi leadership, Nazi leaders were charged with Crimes Against Humanity, a completely new category of crime designed by the victorious Allies to try to deal with the enormity of what they still called “Nazi atrocities.” Thanks to SS documentation, the Allies correctly calculated that the death toll of Jews murdered by the Third Reich amounted to roughly six million individuals, and the basic mechanisms of deportation, slavery, and gassing were also clear.

Even though Allied authorities were able to piece together the basic characteristics of the Holocaust, various aspects remained obscure for decades. Most survivors were deeply hesitant to talk about what they had been through, and even in the newly-founded Jewish state of Israel, most of the focus was on the symbolically-important acts of resistance like a famous uprising of the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1944, rather than on the millions who were killed. For decades, most survivors tried to make new lives, often thousands of miles from their former homes, and most non-Jews were completely ignorant of the breadth, scope, and organized nature of the genocide.

The first systematic study of the Holocaust was carried out by an American Jewish historian, Raul Hilberg, who published his The Destruction of the European Jews in 1961, containing the first highly detailed study of the number of victims, the methods used by the Nazis, and the breadth of the genocide itself. While it took years to mature, the field of Holocaust scholarship began in earnest with Hilberg’s work, eventually burgeoning into a major subfield of history, political science, and sociology. Today, while the scholarship is always turning up new facts and presenting new interpretations, the essential narrative of the Holocaust is well established, based on mountains of hard evidence and meticulous research.

The event that brought the Holocaust to world attention was not scholarship, however, but the capture of the Nazi SS leader Adolf Eichmann in Argentina in 1960 by agents of the Israeli secret service, the Mossad. Eichmann was taken to Jerusalem and tried for his work in overseeing the logistics of the Holocaust. His major job during the war had been to make sure the trains carrying victims ran on time and efficiently delivered them to their deaths. Eichmann was the quintessential “desktop murderer,” a man who (apparently) never personally harmed anyone, but was still responsible for the deaths of millions through his actions. The trial was highly publicized and it began the process of transforming the Holocaust from being only a dark memory of its survivors, largely unknown or overlooked by historians and the general public, to being perhaps the most infamous event of the twentieth century.

In the 1970s and 1980s, a series of films and television programs brought the history of the Holocaust to audiences around the western world, and survivors of the Holocaust began speaking publicly about their experiences in large numbers. Part of the impetus behind the organizations of survivors was the emergence of Holocaust Denial in the 1970s: the hateful, disingenuous, and utterly false claim that the Holocaust never happened (Eichmann himself was irritated when asked by early deniers in Argentina to corroborate their claims – he was perversely proud of his role in running an efficient system of mass murder).

Holocaust memorialization had existed in Israel since the 1940s, but it became much more widespread by the 1980s. One of the most significant memorials to the victims of the Holocaust is the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, conceived of by a commission brought together by President Jimmy Carter in 1978 and ultimately dedicated by President Bill Clinton in 1993. Certainly, by the 1990s, the Holocaust was an integral part of history taught in schools and universities almost everywhere; while it is possible not to know many of the details, even people with only a cursory understanding of modern history are usually aware that the Nazis carried out the genocide of the Jews of Europe during World War II.

18.6 Conclusion

The Holocaust was one of the great traumas associated with World War II. It forced the Western World to confront the fact that a highly advanced, “civilized” nation at the heart of Europe – Germany – had been responsible not just for a initiating a horrendously bloody war, but for carrying out the systematic murder of millions of completely innocent people. The conceit that “Western Civilization” was the most just and desirable matrix of law, politics, and culture was permanently undermined in the process. Since the ancient Greeks, the proud distinction between civilization and barbarism had been upheld in the minds of the social and political elites of the “West,” and yet it was some of those very elites who perpetrated the ultimate act of barbarism in the twentieth century.

Questions for Discussion

- How did the events of the Holocaust set World War II apart from other wars and even other acts of brutality committed by the German army during this war?

- How were attitudes towards race and ability central to the ideology of the Nazis and their actions against the Jews and other people they targeted? In what ways have we seen the roots of the Holocaust in earlier times we have studied in this textbook?

- Why, when, and how did Holocaust remembrance become an important feature after the war had ended? What is crucial about keeping this memory alive today?

Image Citations

Kristallnacht – German Federal Archives

Warsaw Ghetto– Public Domain

Einsatzgruppen – Public Domain

Buchenwald Survivors – Public Domain

Bodies at Gusen– Public Domain

For Further Reference:

Holocaust Encyclopedia, The United Staes Holocaust Memorial Museum, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/

“The Persistence of Antisemitism,” at Facing History and Ourselves, https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/persistence-antisemitism

“What Was the Holocaust?” at Imperial War Museum, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/what-was-the-holocaust

This chapter contains a remix of text from the following:

The main text is taken from Christopher Brooks, “Chapter 11: The Holocaust” in Western Civilization: A Concise History Volume 3, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Original material in the text boxes and the inclusion of a “For Further References” section by Nicole V. Jobin, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.