Comp 1.2: Analyzing Language & Rhetoric

Purpose: Equip students to critically examine how authors use language and rhetorical strategies to influence meaning, intention, and audience response—laying the groundwork for their own persuasive writing.

After looking more intently at how they can bring their own voice to their writing in unit 1, students are ready to start identifying decisions other writers have made. This unit asks students to consider the effects of different rhetorical choices.

The seven readings in this unit offer multiple perspectives about language and rhetoric for students to chew on:

- exploring the many definitions of rhetoric

- applying inherent rhetorical knowledge

- incorporating figures of speech

- examining the concept of exigency

- broadening the application of rhetoric

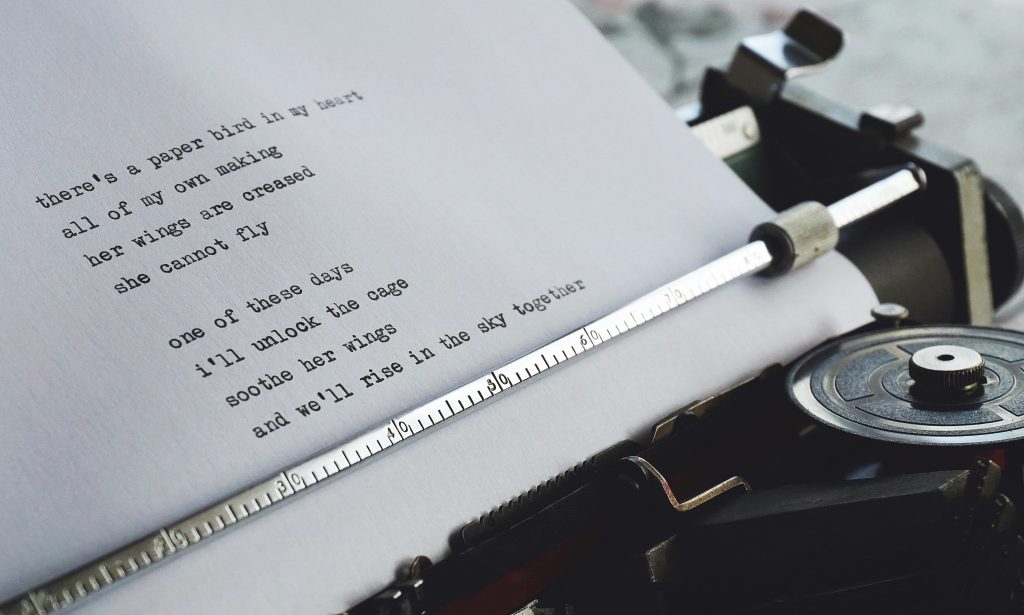

- understanding visual rhetoric

- utilizing invention strategies

Ideally, the unit would end with students writing an analysis paper that connects the language and design choices of a text to its perceived effects.

Instructors can use the overview descriptions below to help decide which chapters might best fit your students. You’ll also find discussion questions for each chapter as well as some teaching resources in Appendix A and B (linked below).

1. What Is Rhetoric? A “Choose Your Own Adventure” Primer

by William Duffy

Author’s Overview — Providing an introduction to rhetoric is a foundational component of most first-year writing courses.1 Discussion of rhetorical appeals, for example, is standard fair in these contexts, as are activities that ask students to develop an appreciation for rhetorical situations, audiences, purposes, and even more nuanced concepts such as kairos and genre. Unfortunately, it’s easy for these concepts—along with the idea of rhetoric itself—to get taken up in these contexts as yet another set of keywords that have static and/or underdeveloped definitions, which in turn limits the ability for students to productively wrestle with the complexities of rhetoric as a resource for their own development as writers. This essay serves as an introduction to rhetoric, but it does so through the medium of a “choose your own adventure” narrative. Divided into ten sections, each of which contains a handful of rhetoric definitions that highlight one of its many qualities, this essay invites students to let their own interests guide how they come to understand rhetoric.

Discussion Questions

- How did you end up reading this essay? Go back and retrace your steps: What sections did you read and in what order? Spend a few minutes reflecting on what this experience says about you. Why did you skip certain sections? What sections were most interesting and why?

- What is at stake in defining rhetoric as either a science, an art, or both? That is, why does it matter (or not matter) whether we identify rhetoric using these categories?

- The definitions in each section of this essay are meant to highlight a specific aspect or quality of rhetoric, so the definitions in Section 4 relate to how rhetoric can mean effective communication, the definitions in Section 5 relate to how rhetoric can mean persuasion, etc. But many of these definitions could be classified under more than one section. Pick one definition from this essay that you think could be moved to at least two other sections and explain why.

- Pick three of the most recent emails you have either received or sent. Thinking about the different approaches to understanding rhetoric outlined in this essay, how would you characterize each of these messages as examples of rhetoric?

- Invent your own definition of rhetoric. You can make one up from scratch, or you can select ideas or phrases to patch together (this is call “patchwriting”) from any of the definitions included in this essay. Once you have a working definition, spend a few minutes freewriting about the choices you considered as you created this definition.

2. Backpacks vs. Briefcases: Steps Toward Rhetorical Analysis

by Laura Bolin Carroll

Author’s Overview — Students are digital natives who spend their days saturated in rhetorical messages that they have learned to decode quite well—for example, they can easily size up an instructor within moments of walking into the classroom. As students look at various messages from fashion advertising to political campaigning, they often decode and make sound rhetorical conclusions about these messages. This chapter helps students understand the rhetorical skills they already possess, transfer these skills to classroom projects, and become familiar with basic terms of rhetorical analysis used in the academy.

Discussion Questions

- What are examples of rhetoric that you see or hear on a daily basis?

- What are some ways that you create rhetoric? What kinds of messages are you trying to communicate?

- What is an example of a rhetorical situation that you have found yourself in? Discuss exigence, audience, and constraints.

3. Writing with Force and Flair

by William T. FitzGerald

Author’s Overview — Exposure to rhetorical figures, once central to writing pedagogy, has largely fallen out of favor in composition. This chapter reintroduces today’s students to the stylistic possibilities of figures of speech, drawing on an analogy to figure skating to illustrate how writing communicates with an audience through stylistic moves. In an accessible discussion of how and why to use figures, it provides an overview of the most common tropes (e.g., metaphor, hyperbole) and schemes (e.g. isocolon, anaphora) and offers brief definitions and examples to illustrate their variety and ubiquity. It discusses the situated nature of writing to acknowledge that while even academic writing employs rhetorical figures, not all figures are appropriate for every genre and context. The essay concludes with a set of style-based exercises to supplement a writing course. These include maintaining a commonplace book, analyzing texts, imitating passages, and practicing techniques of copia for stylistic flexibility. Some resources are recommended for further study.

Discussion Questions

- Which figures in this essay or elsewhere do you want to experiment with in your writing?

- What figures in writing by others do you admire and wish to emulate? After reading this essay, can you better recognize figurative devices, if not necessarily by name?

- What can you learn about writing as a craft from Erasmus’ exercise in copia? How could you push past 50, 100, or even 200 variations?

- What rhetorical figures are appropriate for academic writing? What rhetorical figures are inappropriate for academic writing? What borderline cases can you identify for particular figures?

- Now that you know a little more about rhetorical figures, can you identify any that seem to you to be part of your stylistic tool kit in your everyday writing, perhaps on social media?

4. Exigency: What Makes My Message Indispensable to My Reader

by Quentin Vieregge

Author’s Overview — This essay defines the word exigency and explains its value as a way of gaining and holding a reader’s interest. Exigency is defined as not simply explaining why a topic matters generally, but why it should matter specifically at this time and place and for one’s intended readership. Four different strategies for invoking exigency are given with specific examples from student writing, journalistic writing, and trade books to clarify each strategy. Special attention is given to remind students of their rhetorical context, the interests of their readership, their readers’ predispositions towards the subject matter and thesis (sympathetic, neutral, or antagonistic), and the possibility of connecting their thesis with larger issues, concerns, or values shared by the writer and his or her readers. The chapter closes with a discussion of how rhetorical uses of exigency differ depending on the genre.

Discussion Questions

- Can you think of any other strategies for invoking exigency other than those listed above?

- Have you ever struggled to think of a purpose behind your writing for a particular paper? What did you do to resolve this problem?

- What nonfiction texts have you read that made you feel the text’s subject matter was absolutely essential to you?

- Find and read an academic article, political speech, or magazine article that employs one of these strategies. Which strategy does it employ, and how effective is the text at invoking exigency?

- What genres can you think of that are not mentioned in this article? In what ways do authors typically use exigency in those genres?

5. Elaborate Rhetorics

by David Blakesley

Author’s Overview — This essay presents a working definition of rhetoric, then explores its key terms to help you understand rhetoric’s nature as both an applied art of performance and a heuristic art of invention and creation. The definition also situates rhetoric in the social processes of identification and division. The definition goes as follows: “Rhetoric is the art of elaborating or exploiting ambiguity to foster identification or division.” The chapter develops the meaning of rhetoric, art, elaboration, exploitation, identification, and division, modeling a process that anyone can follow with their own definitions of this or any complex concept. In the end, you should see rhetoric as more than “mere rhetoric” or “the art of persuasion.” You will learn to see rhetoric’s presence in all situations that involve people using words and images to teach, delight, persuade, or identify and divide. You will also learn the value of rhetorical listening for understanding the social, cultural, and plural nature of identity and, thus, our capacity for identification (or division) across contexts.

Discussion Questions

- Exploring Rhetoric. Find three uses of the term rhetoric in the news, then explain what these uses reveal about the nature and function of rhetoric. What do these uses of rhetoric have in common? How do they differ?

- Elaborating Ambiguity. Find an important ambiguous term in public life, one people refer to often but that may have multiple or uncertain meanings, then elaborate that ambiguity.

- The word ambiguous derives from the Latin prefix ambi (“both, around”) and the root aġere (“drive, lead”). Ambiguous, according to the Dictionary of Word Origins by John Ayto, carries the etymological notion of “wandering around uncertainly” (22; Arcade, 1990). Its relatives include ambivalent, ambidexterous, agent, and act (the latter two from the root aġere). Ambiguity makes multiple interpretations possible, each of which may be legitimate and thus contestable.

- Exploiting Ambiguity. In some situations, you want to persuade someone to take a specific course of action or to change an attitude. Using the term you chose in #2, choose one of the term’s meanings, then write a paragraph that uses that meaning to change someone’s attitude about it.

- Rhetorician Kenneth Burke once wrote in a concrete poem called a “Flowerish” (a pun on “flourish”), “From the very start, our terms jump to conclusions.” What do you think he had in mind? In what ways do our terms, our vocabulary, determine what can be known? Spoken? Seen? What might our terms filter from view? Provide one or more examples.

6. Understanding Visual Rhetoric

by Jenae Cohn

Author’s Overview — Visuals can dramatically impact our understanding of a rhetorical situation. In a writing class, students do not always think that they will need to be attentive to visuals, but visual information can be a critical component to understanding and analyzing the rhetorical impacts of a multimodal text. This chapter gives examples of what visual rhetoric looks like in everyday situations, unpacking how seemingly mundane images like a food picture on social media or a menu at a restaurant, can have a persuasive impact on the viewer. The chapter then offers students some terms to use when describing visuals in a variety of situations.

Discussion Questions

- In the first section of this essay, you experienced the story of choosing a restaurant to dine out at with your friends. In this story, the different kinds of pictures shaped the decision made. When have you made a decision based on pictures or visuals? How did the pictures or visuals affect your decision exactly?

- In the discussion of the menu from Oren’s Hummus, it’s clear that the organization and design of the information may impact how a diner might decide what to eat. If you had the opportunity to re-design the menu at Oren’s, what decisions would you make? Why would you make those decisions?

- There are six elements of visual design named in this chapter. Which of these elements were new to you? Which were ones you had encountered before? Individually or in a small group, take a look at either a picture of a poster from the Works Progress Administration OR find a photograph from the Associated Press images database and see if you and your group members can identify the elements of design in one or two of the historical posters or photographs. Use the guiding questions in the “Elements of Visual Design” section of the chapter to help guide your understanding of the images.

7. Finding Your Way In: Invention as Inquiry Based Learning in First Year Writing

by Steven Lessner & Collin Craig

Author’s Overview — Conventional literacy pedagogy in secondary education uses the five-paragraph essay to train students to be succinct writers capable of performing in pressured situations, such as state mandated tests. We aim to show students of first-year writing practical steps in transitioning into college writing by providing strategies for breaking out of habits that limit intellectual inquiry. Through learning critical reading, freewriting, and outlining techniques, student writers can compose in multiple genres in the first-year writing course and across the disciplines. These invention strategies can prompt valuable dialogue between teachers and first-year writers making the transition into college-level writing.

Discussion Questions

- How have you generally started your own writing assignments? What worked and didn’t work for you? Are there any ideas you have for invention in writing that are not in this chapter that you would like to add? What are they, and do you think they could help other students?

- Out of the new invention strategies you have learned in this chapter, which do you think would be most helpful as you transition into writing in higher education? Why do you think the invention strategy you choose would work well and in what way do you see yourself using it?