What Can I Add to Discourse Communities?

How Writers Use Code-Meshing and Translanguaging to Negotiate Discourse

Lisa Tremain

Introduction

Let’s say you’re having a meal with your closest family members or friends. And let’s say the conversation at the table is about a recent topic in the news, something everyone has been talking about and about which folks have a wide range of opinions. Pause to imagine how language might be used in this conversation. Who is there? Would some folks at the table use specific words or phrases, hand gestures or voices in ways that only the group might understand? Are there inside jokes that only this group knows? Would there be more than one language spoken or a blend across languages in the conversation? Which individuals would likely lead the conversation and how?

Now imagine you’re having a conversation about the same topic, but you’re in a classroom where you are a student; maybe it’s your first-year writing course. To what extent does your sense of how you’d use language, voice, or gesture about the topic change in this community? How do the people in the classroom make choices about how to add to this conversation—and what would make them feel invited to add to it—or not? How many languages are spoken or blended during the classroom conversation? What kinds of language styles would be valued there, and how are these language styles different from or similar to the conversation at the dinner table?

In this chapter, we’ll look at how we use language in different ways across different discourse communities—and we’ll consider the degree of agency we have to negotiate the expectations for language in these spaces.

In his essay “Understanding Discourse Communities” (Writing Spaces Vol. 3), Dan Melzer explains that we can apply the concept of discourse community to “describe a community of people who share the same goals, the same methods of communicating, the same genres, and the same lexis (specialized language)” (102). Melzer’s definition of discourse community anchors this chapter’s exploration of why dinner table and classroom conversations can feel different. This chapter also explores how specialized language (the lexis) works in discourse communities, and how a lexis can change over time and through negotiated participation. Because we all belong to and move into and out of various discourse communities, we’ll take up (and slightly modify) Melzer’s closing question in his chapter: What can I add to discourse communities?

As members of different discourse communities, we can and do change discourses through the choices we make with language, but the types of language we use (or feel we are able to use) often depend upon power structures, our positionalities, and our type of membership in them. Perhaps, you are a leader in one discourse community and more of a listener in another. Maybe you’re louder and more opinionated with your family or friends (aren’t we all?) and more quiet or formal in the classroom. At some time, you have probably felt like a novice in one community and an expert in another.

No matter what identities we take on across the communities we belong to, we help to shape and change the discourses in them—sometimes to a great extent and sometimes in ways that are hardly noticeable, but that are more powerful than we might think.

Discourse Communities Change Across Time and Through Participation

Melzer’s chapter helps us consider the many features that make up a discourse community through an example that analyzes his guitar jam group. Melzer examines this group through John Swales’ six characteristics for discourse communities, which include a set of commonly understood community goals, mechanisms of intercommunication, and a specific lexis. Language sits at the center of Swales’ characteristics—and language helps us to understand how discourse communities work. But language isn’t just speaking; it’s also gesture and body language, images, and written text.

The ways that we use our language resources in any given discourse community—as speakers and writers—changes depending on the values, common practices, and the lexis, dialect, or vernacular “rules” that we learn and use in them.

Discourse communities are also fluid; they are always changing across time and as participants move in and out of them, though some discourse communities are more fluid than others (we’ll discuss this a bit later in this chapter). This means that language expectations are negotiated across time and participation. When I was a high school teacher in the early 2000s, for example, students often appreciated something or someone in their peer group by saying it was tight, as in “That movie was tight.” A few years later, the appreciative term changed to sick, as in “Our beach trip was sick.” But neither of these terms was used in the same ways a decade or so earlier when I was in high school. Back then, pants were tight or the dog was sick, maybe, but we weren’t appreciating either. And because I was the teacher (and not part of the student peer group), it would have been humorous if I told my students “This play we’re about to read is sick.” As you’re reading this, there are likely new terms of appreciation you might be using in peer settings—terms that you wouldn’t use in other settings or that someone with a different identity could only use ironically or badly. This is just one example that exhibits the ways that languages are always shifting and evolving, and they do so through use, location, and time.

It might seem obvious to say that languages change over time and are used differently across different groups. But take a second to think about how many different groups (or discourse communities) you already belong to. How have you—consciously or not—learned and practiced the expectations of language in each of them? Teams, clubs, campus groups, workplaces, online groups, gaming communities, and undergraduate major programs are all examples of discourse communities you are or likely have been a member of at one time or another. The discourse that is used in and across these groups changes through members’ negotiation of language over time. In the following section, we’ll test this claim by examining a popular internet meme.

Tracing a Discourse: The LOL Cats and Internet Meme Aesthetic

The term meme is derived from the Greek word memeia—that which is imitated. A meme is a genre, and different memes become dominant in a discourse through retention and repetition. Memes, like language, are a genre we learn and practice through imitation. I’m sure you can think of more than one popular meme, and you might have even designed a few memes yourself. As a textual genre, a meme shows us not only what we were thinking about a particular topic at a moment in time, but also how we applied, negotiated, or resisted language rules in this textual form. As a genre, memes use language and image to become an expression of culture shared by particular groups of people. Any one meme is like a signpost on a giant map of how language is used on the internet. By tracing memes across time and communities, we can explore how rules for language change through participation.

Consider the (now pretty ancient) LOLcat meme (fig. 1).

So, why the cat? Why does the cat ask to haz as opposed to have a cheezburger? What does this meme mean? Though we know that cats don’t really eat cheeseburgers (or cheezburgers), there are literally thousands of cat memes with “haz” in place of “have” in them, including memes of cats asking, “I can haz cat memes?” This genre is culturally known as the LOLcats meme, and this particular image was made with a meme generator for a burger restaurant. LOLcats memes are cousins of (or intertextual with) other genres, such as viral cat videos and cute kitten images and gifs—and they are one of the earliest examples of the internet meme.

A function of the LOLcats is that they present us with an archive of early internet aesthetic, a genre where writers designed and posted digitized blasts of communication through images and words, usually for comic effect. LOLcats memes capture and interpret cultural practices at one point in time, and they present us with the expectations for language in this meme-specific genre and discourse. We immediately know this is an LOLcats meme not only because it shows a cat, but because it uses the internet language forms of plz and haz. The LOLcats memes are an example of how a discourse community uses language, including visual and linguistic patterns to reveal, develop, contribute, or change a cultural practice or to establish a user’s membership in the community.

Other discourse communities have taken up the genre of the LOLcat meme to speak internally to their members. In fact, while the first LOLcats memes appeared long before there were meme generator sites, now we can play Minecraft in LOLcat language.

[The example video above has been added to this edition of the text.]

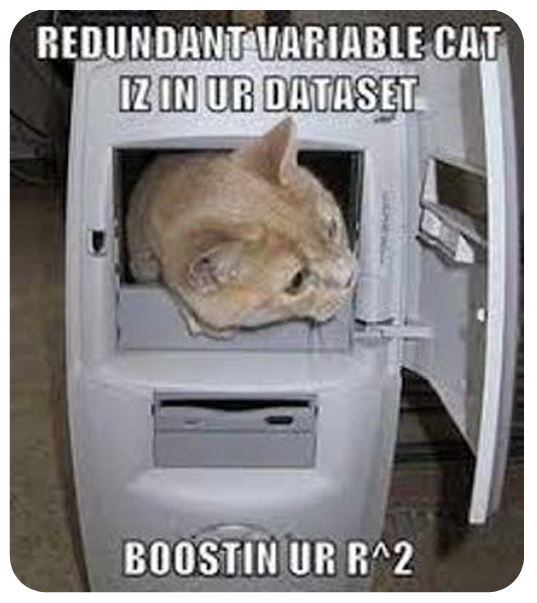

We can also see how specific discourse communities with specialized languages (the lexis) meshed their discourses with the language of the LOLcats, like this example (fig. 2):

Whether you understand the specialized language in this LOLcat meme or not (which uses the lexis of statistics), you can see the LOLcat language conventions of iz and ur. This meme is also highly representative of the statistics discourse community. It uses the disciplinary terms redundant variable, dataset, and r^2, and the joke in it makes little sense to those of us outside of its membership.

You might pause here to take a few minutes to do an image search of meme + one of your favorite hobbies, activities, or areas of study to see what comes up. What kinds of community or cultural practices are revealed through the memes you find? How do these memes reveal the language expectations of the community? This same approach can occur by examining the genres and language expectations of college majors, workplaces, groups, or clubs.

So far, I’ve attempted to show how, across our lifetimes and even in a single day, we move across complex linguistic landscapes. Still, we don’t simply close a drawer in our brain when we’re done using one discourse and then open another as we move across communities.

Regardless of the group we’re in at any given moment, our brain wants us to use all of our linguistic resources to communicate and connect with one another, to develop ideas, to create and design and live.

As we navigate the expectations of a discourse community, we draw from and creatively adapt our language resources to communicate. The ways that we have learned and experienced language, especially the language(s) or dialects we first learned as children, are always present, always part of our tool box, no matter what discourse community we are navigating.

At the same time, language is inseparable from power. Sometimes we are asked to perform certain kinds of language to show the worthiness of our membership in a discourse community. Sometimes the way we are asked to perform language is connected to a paycheck or a promotion or a grade. And sometimes we are asked to deny a way that we speak or write. Language is not neutral.

While practicing and using a specialized lexis does help us to establish membership and identity in the discourse communities we belong to (or want to belong to), it can sometimes feel like we need to hide languages or discourses we know and value.

When we make and share a meme on the socials, the stakes aren’t as high as they are as when we write for a college course assignment or draft an email to request a raise at our job. As Melzer points out, you may “find yourself struggling a bit with trying to learn the writing conventions of the discourse community of your workplace” (110) or your major or any other specialized group. How, then, do we use (and show the value of) the language resources we already have and, at the same time, how can we practice and learn the language expectations of a specific discourse community?

There Is No Single Story for Writing and Speaking

Consider, once again, the differences between the conversations at the dinner table and the first-year writing classroom. It’s unlikely that the conversational rules and language expectations are exactly the same across these two situations. We are consciously (and often unconsciously) aware that there are certain ways to use language (and certain languages) in certain spaces. These ways of knowing highlight the very deep relationships between language, identity, and power.

Through our experiences as readers and writers, especially in school settings where we are required to learn communication and language skills in what is known as “standard English,” we tend to internalize beliefs about how language (and English) works. Sometimes this looks like a single story of speaking or developing a belief about how writing “should be done.” It also means we have been trained to evaluate others based on their ability or willingness to “do it the way it should be done.”

But a focus on standard English (also known as Edited American English in the U.S.) as the achievable and desirable mode of “correct writing” is far too simplified to help us deal with the writing and communication we do in the world every day. The teaching of standard English rarely includes a transparent acknowledgement that requiring it upholds White Western norms and values about “correct” speaking and writing. Mara Lee Grayson speaks to the ways pervasive requirements to use standard English across discourse communities uphold Whiteness and White supremacy in her essay “Writing Toward Racial Literacy”: “These so-called rules have been passed down through systems and people, like schooling and teachers, for so long that we might think they’re the only way to write” (168).

But in fact, “correct” writing and language use—including certain kinds of English—are constructions or beliefs; they have become standards because people (often people in power) have made them so. When you take a close look at how language rules function differently across communities, you can see that “correctness” is contingent and flexible.

As Meltzer tells us at the end of his essay, “Discourse community norms can silence and marginalize people, but discourse communities can also be transformed by new members who challenge the goals and assumptions and research methods and genre conventions of the community” (110). How we make certain choices about language is shaped by each discourse community we are part of, by the communicative situations in them and by their norms or “rules” for language—rules that we learn, break, and participate in changing. While language often functions as a gatekeeper, letting some folks into a community while keeping others out, language rules are also always in negotiation—between speaker and listener, and between writer and audience.

Language That Negotiates Discourse Community Expectations: Translanguaging and Code-meshing

Translanguaging and code-meshing are two frameworks that can help us see language in negotiation. These frameworks can help us understand our various linguistic resources as we navigate—and potentially challenge or change—the expectations of discourse communities. Translanguaging and code-meshing are especially useful in helping us see the ways that language, identity, and power intersect—and how much linguistic agency we have in the discourse communities that we are (or hope to be) part of.

Translanguaging can be understood in part by looking at the Latin root trans (to cross); when we cross or blend languages in order communicate, we are translanguaging. Hybridized cultural languages, such as Spanglish, are examples of how translanguaging works. Examples like “Actualmente, I will join you,” or “Wacha le” show translanguaging in action. We also commonly see translanguaging in internet speak, like “I googled it” or “It was gr8 to see you.” People don’t use translanguaging without purpose; rather, we translanguage to help us communicate creatively and accurately with others. When we translanguage, we create and co-construct new meanings for and values about how language works in discourse communities.

While translanguaging blends languages, code-meshing occurs when we mesh dialects (or codes) of one language as we speak or write. In English, for example, we might consider y’all as a regional term associated with Southern United States dialects. Code-meshing is similar to translanguaging in that when we use it, we are performing a type of membership. If I write in this essay that I hope y’all are able to observe or use translanguaging and code-meshing in college, I’ve meshed the sentence to include a regional southern English dialectical term with the more academic English language I’ve primarily used to shape it. Yet I am almost sure you’ve had a teacher that would correct you if you used y’all or gr8 or actualmente in an essay or research paper for school; you also probably wouldn’t use sick or tight as an appreciative term in an academic text.

In other words, we often consider and do our best to apply the rules of “acceptable” discourse in each situation, and what’s “acceptable” is generally the discourse that we recognize as dominant in the community. This is because we understand that many discourse communities, including academic or college-level disciplinary communities, require highly specific forms of language of their members. Meeting these requirements means knowing the right terms (or lexis) to use, but also the right kind of English.

But cultivating a sense of how (and how often), as a writer or speaker, you and others can use translanguaging or code-meshing can reveal the negotiated nature of communication in discourse communities. For example, translanguaging and code-meshing in certain communities can be beneficial: these practices can help writers share or create new meanings and knowledge, and they reveal the degree of linguistic flexibility we might have in a discourse community. However, translanguaging and code-meshing can also be risky: by using them, a writer or speaker might fail to meet a discourse community’s standards, which could mean losing a job, lower grades, marginalization, or exclusion.

In her well-known essay “How to Tame a Wild Tongue,” Gloria Anzaldua reflects on these tensions, including which languages to speak—and when—in relationship to her Chicana identity:

[B]ecause we internalize how our language has been used against us by the dominant culture, we use our language differences against each other. … Even among Chicanas we tend to speak English at parties or conferences. Yet, at the same time, we’re afraid the other will think we’re agingadas because we don’t speak Chicano Spanish. … There is no one Chicano language just as there is no one Chicano experience. (58)

Like English, as Anzaldua notices, there is no one Chicano language. She notices the ways that the English language has been used to assert dominance, to gatekeep, and to exclude. If Chicano Spanish or y’all or gr8 are all part of a writer’s or speaker’s linguistic knowledge, what happens when that knowledge is not valued inside a discourse community?

In requiring each member of the discourse community to use (and be fluent in) its discourse (for example, standard English), it stands to reason that some members of the discourse community advance more quickly when they perform language the “right” way, while others do not. And because language gatekeeping continues to occur, some folks might believe that having fluency in the dominant discourse is necessary for success. But it’s useful to interrogate these claims. How does language gatekeeping work in relationship to membership and power in a discourse community? Whose language is allowed to thrive in the discourse community and whose is not? In one of his many scholarly essays in support of code-meshing, Vershawn Ashanti Young argues against the idea that “prescriptive standard English is all that students need for academic and financial success” (140). Instead, Young argues that

When we operate as if it’s a fact that standard English is what all professionals and academics use, we ignore that real fact that not all successful professionals and academics write in standard English. We ignore the many examples of effective formal writing composed in accents, in varieties of English other than what’s considered standard. Further, we ignore that standard English has been and continues to be a contested concept. (144)

When we take a step back and see the various ways we use language in our lives—and how our individual approaches to language are constantly being negotiated across discourse communities, we can see that standard English is a contested concept.

A broadly constructed understanding of English asks us to understand and acknowledge that, in the same ways that there are multiple languages and discourses, there are multiple Englishes.

What Can I Add to the Discourse Community?

When it comes to written communication, we can acknowledge translanguaging, code-meshing, and Englishes as flexible ways to communicate rather than right or wrong ways to communicate. Aimee Krall-Lanoue suggests, “If we believe that language is not fixed or static and that it is shifting according to the needs, desires, and interests of users, we must also ask ourselves […] to critically and intensely read what is on the page rather than what ought to be on the page” (233–4). This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t pay attention to (and probably learn and practice) the codes and expectations of a discourse; rather, it means that we can have a critical awareness of these codes and expectations.

As you attempt different kinds of writing and communication across the discourse communities you’ll join (or want to join), you can assess language expectations through a critical lens. In the essay “Beyond Language Difference in Writing: Investigating Complex and Equitable Language Practices,” author Cristina Sánchez-Martín suggests that we ask: “[H]ow much space for language difference is there in this type of writing? Are the audiences receptive to it? […] What would happen if I decide to ignore the audience’s preferences?” Sánchez-Martín encourages us to “look at the larger situations, ideologies, histories, and conditions that put us, writers, in a position to really be strategically ‘linguistically diverse’ in our writing on our own terms” (276–77).

While a specific lexis helps establish the boundaries of what makes a discourse community, the specialized language in it can be negotiated and transformed through a type of a balancing act.

On one side, members develop and progress in a discourse community as they learn to enact its values and beliefs by writing and speaking in its specialized language and genres. On the other side, members can and do participate in shifting a discourse community’s communication practices and values by purposefully making language choices that reflect our hybridized identities, multiple literacies, linguistic backgrounds, and cultural heritages.

Another way to think about the balancing act of negotiating discourse: as the expectations of a discourse community acts upon us, we also act upon it.

We change discourse communities by bringing our prior knowledges, especially our social, cultural, linguistic and discoursal knowledges to them. Because we work, live, and write across a range of cultures and communities, we must engage in conscious efforts to think about how attitudes about and practices of writing and communication are negotiated in them.

We also might seek to understand, as writers, how, why, and when we alter our writing (or the genres we use) to address the needs of various cultures and communities.

Works Cited

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands = La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books, 2007.

“Can I Haz Cheezburger Plz?” The Salted Cracker Sandwich Shop Facebook Page https://tinyurl.com/274akjmh. Accessed 4 June, 2022.

Grayson, Mara Lee. “Writing toward Racial Literacy.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 4, edited by Dana Lynn Driscoll, Megan Heise, Mary K. Stewart, and Matthew Vetter. Parlor Press, 2021, pp. 166–183.

“I Played Minecraft in the LOLCAT Language.” YouTube. https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=Nbgjaoww4Rs. Accessed 1 June, 2022.

Krall-Lanoue, Aimee. “‘And Yea I’m Venting, but Hey I’m Writing Isn’t I’: A Translingual Approach to Error in a Multilingual Context.” Literacy as Translingual Practice: Between Communities and Classrooms, edited by A. Suresh Canagarajah, Routledge, 2013, pp. 228–234.

“Lolcats.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lolcat. Accessed 1 June, 2022.

Melzer, Dan. “Understanding Discourse Communities.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 3, edited by Dana Lynn Driscoll, Mary K. Stewart, and Matthew Vetter, Parlor Press, 2020, pp. 100–115.

“Redundant Variable Cat Iz In Ur Data Set.” Keynesian Cat Facebook Page. https:// tinyurl.com/mr3fxudy. Accessed 4 June, 2022.

Sánchez-Martín, Cristina. “Beyond Language Difference in Writing: Investigating Complex and Equitable Language Practices.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 4, edited by Dana Lynn Driscoll, Megan Heise, Mary K. Stewart, and Matthew Vetter. Parlor Press, 2021, pp. 269–280.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti. “Keep Code-Meshing.” Literacy as Translingual Practice, edited by A. Suresh Canagarajah, Routledge, 2013, pp. 139–146.

*This article originally appeared in Writing Spaces Volume 5 and can be viewed here in its original format.