Thinking Across Modes and Media (and Baking Cake)

Two Techniques for Writing with Video, Audio, and Images

Crystal VanKooten

Introduction

When it comes to dessert, who doesn’t love cake? It’s soft, rich, and sweetly decadent. But if you’ve ever made a cake from scratch, you know that there are many elements that a baker uses to put together and finish the cake: flour, butter, sugar, eggs, salt, filling, and frosting. These elements are combined—or integrated—differently depending on how the baker wants the cake to turn out. Put another way, what goes into the mix makes a difference in how the cake tastes in the end.

Much like cake, multimodal texts such as videos, websites, posts on social media, and podcasts involve a variety of elements that are combined to make a final product: words, images, sound recordings, music, voices, and video clips, for example. Like master bakers, skilled digital writers know how to combine these elements strategically, sometimes layering several of them together to compose a new whole or sometimes emphasizing one particular mode.

This chapter will introduce you to two writing techniques, integration and juxtaposition, that can help you better understand and describe different combinations of media in a multimodal text, and also help you to compose your own digital product that audiences will really enjoy—to bake your own delicious cake!

But let’s be real here: I’m a professor. I’m no master baker, and you probably aren’t either. If I’m baking a cake, I’m going to read and follow the directions on the back of the box, and those directions will help me to put the cake ingredients together in a way that—I hope—is really tasty! This chapter is kind of like one set of simple directions on the back of the cake box for your digital writing, a place to start when considering how to describe the modes and media that others put together, and how to use those same modes and media to compose your own work. I’ll draw from writing professors and digital designers to talk about what integration and juxtaposition are in relation to writing with video, audio, and images, and I’ll show you what these two techniques can look and sound like in one student-authored video made for a writing class. Ultimately, knowing how to recognize, describe, and use these techniques will help you approach the analysis and composition of your own and others’ multimodal texts with more specificity, confidence, and control.

What Is a Multimodal Text?

At this point, you may be wondering what exactly a multimodal text is, and why in the world I’m talking about baking in a chapter about digital writing. We’ll get there. For now, just stay with me, and think of a multimodal text as a soft and delicious cake that you want to bake for your sister’s birthday. You go to the store, choose the “Traditional Chocolate” cake mix, and read that you need to combine cake mix, water, oil, and eggs to make the cake batter. So into the bowl they go, and then, using a spoon—or for those of you who are fancy bakers—a mixer, you stir them together. Next, you bake the cake, let it cool, frost it, and it’s ready to eat! When you and your sister put your forks into a slice, you no longer see the powdery mix, or the water, or the eggs. All of the individual ingredients were integrated to create the fluffy, chocolatey dessert you can enjoy. After it’s baked, the cake is now what writing professor Bump Halbritter would call “all-there-at-once,” meaning it’s a whole that comes across as if it isn’t comprised of parts and pieces. The baker knows, of course, that many ingredients were combined strategically to make the whole, and those combinations can really affect the taste, texture, and flavor.

This concept of combining elements strategically is useful for cake baking and for composing multimodal texts, which of course is why we’re spending so much time in this chapter on cake.

But what is a multimodal text, anyway? The term mode is embedded in the word multimodal, and when I talk about a mode, I’m referring to what writing professors Kristin Arola, Jennifer Shepherd, and Cheryl Ball describe as “a way of communicating” (3). When you compose a multimodal text like a video, you blend together images (the visual mode), sounds (the aural mode), and written words (the linguistic mode), much like you mixed together the ingredients for your sister’s cake. Writing Spaces volume 3 author Melanie Gagich clarifies that text is a broad term in writing studies that refers to “a piece of communication that can take many forms” (66). So a multimodal text is a piece of communication that uses multiple ways—or modes—to get its message across.

Arola, Shepherd, and Ball, along with Gagich, also point out that there are many different kinds of multimodal texts that are both digital and non-digital: movies, memes, posters, online articles, slide decks, whole websites, and more. And just as a baker might vary the amount of different cake ingredients to get a different texture or taste, the modes in each different kind of multimodal text can be blended together in various ways. But in baking, you can’t experiment with blending if you aren’t aware of the ingredients and the effects they can have on cake-eaters, and the same applies for digital media composition. You can’t become an advanced digital media author if you don’t know how to see and hear past a media product’s “all-there-at-onceness.” Halbritter advises that we need “an ability to break apart the components” of digital media texts, along with “terminology that identifies and names the relationships within and between the rhetorical elements of a complex piece of audio-visual writing” (108). This is where concepts like modes, integration, and juxtaposition are helpful. They give us language to talk about how digital texts are composed and how they affect audiences.

Integration

Integration is defined by professor and political scientist Robert Horn as “the act of forming, coordinating, or blending into a functional or unified whole” (11). In his book about visual language, Horn gets more specific about the integration of words and images, and he talks about nine different kinds of integration of verbal and visual elements: substitution, disambiguation, labeling, example, reinforcement, completion, chunking, clustering, and framing (101–104). I could say a lot about how any of these kinds of integration might apply to our work with digital media, but I’d like to focus us on reinforcement, in part because I’ve noticed that student writers use this technique a lot—sometimes even a bit too much. According to Horn, visual/verbal reinforcement happens when “the visual elements help present a (generally) more abstract idea. They present the idea a second time, even though it may be clearly interpretable from the words alone” (103).

So we could call reinforcement “doubling” or “cross-modal repetition,” where an author presents one concept through two (or more) modes of expression: through words and images, for example, or through images and sound.

Like I said, I’ve noticed that students tend to use reinforcement a lot when they’re new to composing digital compositions. They’ll write out a point in a video using words while they simultaneously speak the same exact words in a voiceover. They’ll write out facts about a topic on a PowerPoint slide, and then pair the words with a graph that shows the same information. These examples use reinforcement across modes in simple ways, and sometimes, simple is good. A graph might help us see data differently than only reading about it, for example. Many times, though, when authors use cross-modal reinforcement, the visual and the verbal reinforce each other, but for little apparent reason.

Instead, when reinforcement is used to further a specific rhetorical purpose, it can be a useful form of integration. Horn mentions that when using visuals to reinforce words, “visual elements add rhetorical qualities such as mood, style, lightness, and so forth” (103).

Applying this idea, an image might be combined with some words not just to use two modes together because we can, but instead to create a specific mood or style like seriousness or whimsy.

In addition, disability studies scholar Stephanie Kerschbaum writes about reinforcement using the term commensurability, when information is repeated via multiple channels in order to provide greater access for all users and readers. As Kerschbaum makes clear, making digital texts more accessible for audience members with varying abilities is a very good reason to use cross-modal reinforcement.

An Example of Integration: Reinforcement in “A College Collage”

Cross-modal reinforcement has a place, then, when done for a rhetorical purpose and/or for accessibility. Let’s talk through an example of what an effective use of reinforcement might actually look and sound like in a multimodal text by looking at a video composed by Evan Kennedy, a student in a writing course that I taught a few years ago. Evan’s video is called “A College Collage: Not Going Back,” and he made it in response to a video composition assignment in our digital writing class. The assignment was very open, asking students to pick any topic to explore through composing a video that used multiple modes to communicate. Evan chose to make his video about managing mental health during college, and specifically, about his own experiences with mental health through an extended college career at multiple schools. He explores and shares about this topic through combinations of images (many of his own selfies and photos), music (Demi Lovato’s popular song “Old Ways”), and sounds (remixed voiceovers from documentary films). I highly encourage you to watch all of Evan’s video [below] before you read any further in this chapter. Next, I’ll talk us through a few sequences where Evan uses different kinds of integration and juxtaposition effectively.

Once you watch the video, you know that “A College Collage” is pretty awesome. For the video’s first minute, we hear different voices speaking about mental illness and its effects along with a low driving beat and a crackling, static sound that replays each time a speaker finishes a phrase. We see an empty black screen that switches between various black and white images: notebooks and textbooks falling off of a desk, a person lying on a bed seen through a small window, stacked pill bottles, a man holding the side of his head. In this sequence, Evan has mixed together some cake ingredients—he’s integrated various media elements such as spoken words, images, video clips, and sound effects.

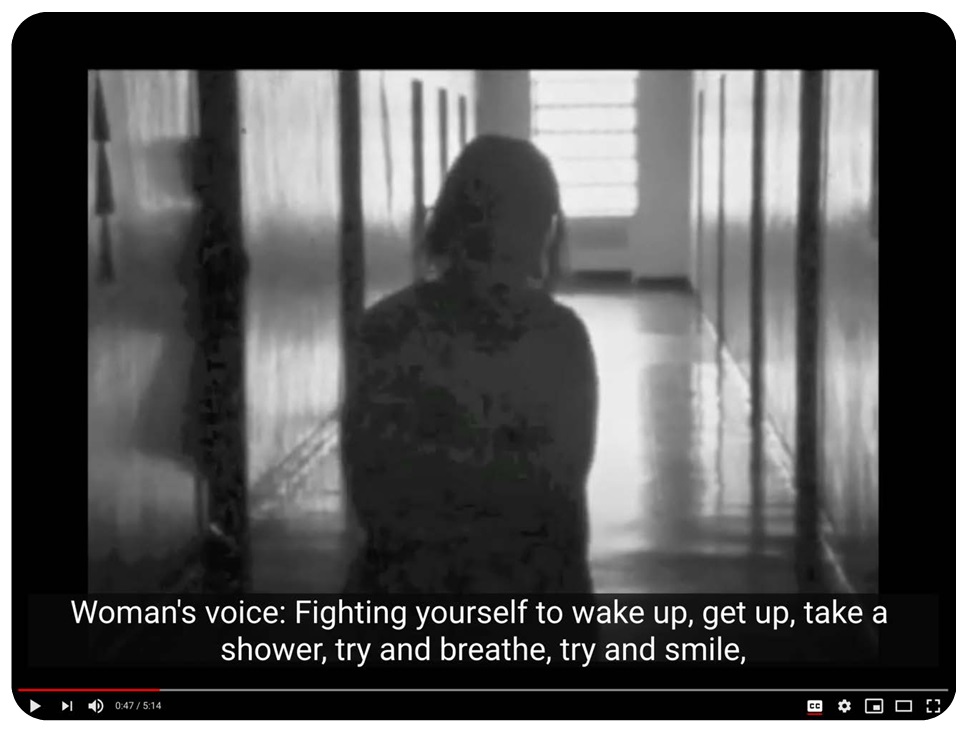

Evan effectively uses reinforcement in this opening sequence with the sounds and images. The excerpt from 0:44–0:51 is a good example. A female voice speaks, saying, “Fighting yourself to wake up, get up, take a shower, try and breathe, try and smile, try and act like you believe you have something to live for.” Through words, the speaker describes one kind of daily mental health struggle, and reinforcing this spoken message is the image sequence that Evan chose to put with it: a female figure, shadowed, who walks slowly toward us down a hall (see Figure 2). But the image sequence doesn’t exactly double the content of the spoken words; it adds a feel and tone, along with more information that allows us to interpret the words. The visual is dark, shadowy, somber. We can’t see the woman’s face. We imagine her struggle to “wake up, get up” as she teeters down the hospital hallway. Together, the words and the image help to communicate the message: that for this woman, it’s difficult to wake up and start the day.

The way Evan mixes his ingredients together in this opening sequence to reinforce one another works for me as an audience member. I see it and I hear it; I get it and I feel it—mental illness is a difficult struggle. I wonder what Evan is going to say next about mental health, and I look and listen for more images, words, and sounds to help me better understand the message.

Juxtaposition

Let’s go back to your sister’s birthday cake. You’ve already mixed the ingredients and baked the cake. Now, you decide to stack two layers on top of each other and put some filling in the middle, along with frosting around the outside and on top. The filling will add more moisture and a contrasting flavor, but it won’t be integrated into the cake in the same way as the other ingredients. It will be positioned next to the other elements for a delicious result. The same is true for the frosting—you smooth it out on the top and sides of the cake, and you taste and enjoy it along with bites of cake and filling.

When you use cake filling in the middle of a cake and frosting on the top and outside of a cake, you’re baking with the technique of juxtaposition, where two or more elements are placed next to one another in a single space or moment “to create meaning and communicate ideas to an audience,” as writing professor Sean Morey explains (288). For cake baking, the juxtaposed elements include cake bites and frosting. For digital writing, the juxtaposed elements include images, sounds, and words.

In a visual presentation, you can place two or more images side by side and create meanings and patterns that emerge from viewing them together. In a video, you can put sounds and images next to or after one another in time (sequentially) or layered on top of each other at the same moment (simultaneously) to create contrast, to tell a story, to compose a transition, and to do many other things.

Anthropologist and museum researcher Corinne A. Kratz analyzes how juxtaposition works in exhibits, installations, websites, and films. She calls juxtapositions “productive kernals” that can do different kinds of rhetorical work: raise questions, tell stories, imply sequence or narrative, provoke puzzlement or surprise, show contrast or similarity, help to make an argument, or suggest categories (30, 32). Juxtaposition can be seen as a form of integration, but I like to think of it as a related technique where elements are placed in close proximity to one another but still remain somewhat separate. It’s layer cake with cake filling; the elements are not fully mixed.

Student writers in my classes use juxtaposition in some of the ways Kratz mentions. For visuals, they often use sequential juxtaposition, where different images are presented in a sequence to tell a story, seen one after the other in progressive time. Students also have used video effects for visuals such as a split screen or a picture-in-picture, which allow for simultaneous juxtaposition as different elements are seen or heard next to or near one another at the same moment in time. The simultaneous juxtaposition of elements can also be composed across modes: images can be placed next to or with sounds or music, for example, or images placed adjacent to written words.

Examples of Juxtaposition: Sequential and Simultaneous Juxtaposition

Let’s return to “A College Collage” and look and listen to one portion where Evan utilizes cross-modal sequential and simultaneous juxtaposition to further the message of his video. After the video’s introduction at 1:21, Evan uses Demi Lovato’s 2015 song “Old Ways” as the soundtrack for the main portion of “A College Collage.” Songs are complex, layered pieces of media in and of themselves, and “Old Ways” is no exception. We hear Lovato’s voice, the lyrics of the song, various instruments, rhythmic beats, and electronic effects. Writing professor Kyle Stedman claims that “music is a language. It speaks. And as such, it’s rhetorically deployed by people who have specific things they want to say with it.” As we listen and watch, we notice that Evan is indeed rhetorically deploying “Old Ways” to do a lot more work than a stock background track might do. Many elements of the song—the beat, the lyrics, the changes in pace—are strategically juxtaposed with the images and words we see, and the images themselves are then juxtaposed carefully alongside each other.

From 1:34–1:51, Evan uses Lovato’s lyrics to start to tell a story of perseverance amid trial. Lovato sings, “I’m down again / I turn the page / The story’s mine / No more watchin’ the world from my doorstep / Passin’ me by / And I just keep changing these colors …” We hear these lyrics simultaneously juxtaposed with images of a growing stack of books on a shelf and a growing pyramid of empty pill bottles on a table. We see the date “2009” written across the screen. The images are placed in sequential juxtaposition, one after the other, and the changing of the images is coordinated with a hard-hitting percussive beat within each measure of “Old Ways.” Hearing this repetitive beat, we anticipate each image change before it appears, and the mix of the images, the date, and the music implies a narrative. We wonder about connections between the modes and media: how are the books and the pill bottles related? Are the pill bottles related to Lovato’s lyric about being “down again”?

This fifteen-second sequence ends as the music transitions from verse to chorus. Within the song at 1:41, an ascending electronic scale grows louder, building in volume and pitch to the first line of the chorus. Evan juxtaposes this musical shift with a video clip that zooms in on a lone figure at the end of a hallway (see Figure 3). According to Kratz, one way juxtaposition works is to coordinate elements to heighten the audience’s attention (30), and we notice Evan using the music and the clip’s zooming movement to do just that—to get us to look and listen closely. As the beat of the chorus drops dramatically, we then see a black and white clip of Evan himself, punching toward the camera on the downbeat, and the visual quickly flips to a red screen with the date “2010.”

There’s a lot going on here. Evan is both juxtaposing and integrating, using images, clips, music, lyrics, and movement to tell the story of his journey through college with mental health. The juxtapositions are sequential (different images one after another) and simultaneous (music with image); they are within and across visual and aural modes, and they help to make watching this video a captivating and persuasive experience. And the purposes of these juxtapositions are various and align with Kratz’s list, working to imply a narrative (of Evan’s experiences across time), to heighten attention (to a transition point in the story), or to point out similarities (between Lovato’s lyrics and Evan’s experiences).

Baking (and Sharing) Your Own Cake

“A College Collage” is chock full of many other moments of integration and juxtaposition that you can watch, listen to, and learn from. It’s important to tell you, though, that Evan worked on this video across a span of eight weeks in our writing course. He turned in four different versions of the video, and he was constantly making revisions, listening to feedback from me and others in the class, and going back and making more changes. (If you want to see some earlier versions of “A College Collage,” you can view three earlier drafts at this link, where I write more about Evan’s composition process). The point is that composing these kinds of complex and powerful media sequences takes time, effort, input, and lots of revision. Part of the effort that Evan put in was learning how to see and hear his own work both as “all-there-at-once” and as component pieces that could be tweaked and changed, juxtaposed and integrated in different ways. Then he “taste-tested” his video by giving it to audiences to try, and using their feedback, he went back to the kitchen to mix in different elements that might taste even better.

You can do the same as you read and analyze multimodal texts composed by others or compose your own multimodal texts for class.

Think about the whole, and then think about the parts that make up the whole. Taste the cake when it’s done (watch the video, read the presentation), and get others to taste it too, during peer review sessions, at the writing center, or anywhere you can get someone to give you feedback on your work. Pay attention to what ingredients you’re using and why, listen to feedback on how they come together, and be ready to make changes and taste-test again.

If you’re making a PowerPoint presentation, be mindful of how your words and images work together. Is there too much reinforcement between modes? How can you use images to reinforce words or words to reinforce images, but not to simply double the meaning? What images could you use that add value to the words, that might reinforce through an example or through new information? If you’re making a video composition, consider and plan how you might juxtapose the modes and media the audience sees and hears. Can you use side-by-side visuals, and if so, what would the effect be on the audience? Can you do more with aligning elements of the musical track with visual and written elements, and how might doing this advance your purpose? Can you tell a story across modes, create a surprising visual moment, or imply a connection between parts?

Thinking critically and concretely about integration and juxtaposition in the multimodal texts you consume and create is one step toward becoming a more skilled and rhetorically-sensitive digital writer. They’re simple concepts with many different applications and outcomes when used across modes and media. And when you can spot them, think about them, and then use them purposefully, you are well on your way to master baker status, digital media style.

Works Cited

Arola, Kristin L., et al. Writer/Designer: A Guide to Making Multimodal Projects. 2nd ed., Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2018.

Gagich, Melanie. “An Introduction to and Strategies for Multimodal Composing.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, vol. 3, edited by Dana Driscoll, Mary Stewart, and Matt Vetter, Parlor Press, 2020, pp. 65-85, https://writingspaces.org/?page_id=384.

Halbritter, Bump. Mics, Cameras, Symbolic Action: Audio-Visual Rhetoric for Writing Teachers. Parlor Press, 2013.

Horn, Robert E. Visual Language: Global Communication for the 21st Century. MacroVU, Inc., 1998, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL400850M/ Visual_language.

Kennedy, Evan. “A College Collage: Not Going Back.” YouTube, uploaded by Crystal VanKooten, 9 April 2019, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=RgX4U7Z25c0.

Kerschbaum, Stephanie. “Modality.” “Multimodality in Motion: Disability and Kairotic Spaces” by M. Remi Yergeau et al. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 18.1, 2013, https://kairos.technorhetoric.net/18.1/coverweb/yergeau-et-al/pages/mod/index.html.

Kratz, Corinne A. “Red Textures and the Work of Juxtaposition.” Kronos, no. 42, Nov. 2016, pp. 29–47, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44176040.

Morey, Sean. The Digital Writer. Fountainhead Press, 2017.

Stedman, Kyle D. “How Music Speaks: In the Background, In the Remix, In the City.” Currents in Electronic Literacy, 2011, http://currents.cwrl.utexas. edu/2011/howmusicspeaks.

*This article originally appeared in Writing Spaces Volume 5 and can be viewed here in its original format.