“I Passed First-Year Writing—What Now?”

Adapting Strategies from First-Year Writing to Writing in the Disciplines

Amy Cicchino

Introduction

“C minus?!” Angel was stunned. Angel was not a C- student; they had always done well in writing courses in the past and had just earned an “A” in Composition II last semester. Yet, while looking at their grade for their first writing assignment in BIO 2030, they began to doubt their ability.

Professor Smith introduced the assignment six weeks ago, and it seemed simple enough: each student would create a scientific poster on a series of lab experiments they had completed on the culturable microbes they had found in dirt samples. The assignment sheet told students to create a poster for a scientific audience with complete sections and a polished design. Sure, Angel hadn’t started the assignment until a few days before it was due, but the professor hadn’t asked to see drafts before the final due date.

Angel brought up the poster when they went to lunch with their friend, Akeelah, who was also in the class. “How did you do on the poster project?” Angel asked.

“Okay,” Akeelah said absentmindedly.

“What is okay?” Angel pried.

“B minus,” Akeelah said, putting down her phone and turning her attention more towards Angel, who was obviously concerned about the assignment, “Why?”

“I got a C minus,” Angel admitted, “I’m a good writer. I don’t understand what Prof. Smith wants from me.”

“Have you thought about asking?” Akeelah posed, “You can go and talk to her during office hours. That’s what I did. It was weird at first, but I felt a lot better afterwards.”

Angel shrugged; they hated having awkward conversations with professors. “Can’t I just see your poster?”

Akeelah paused, “I’ll show you my poster, but only after you talk with Prof. Smith.” Angel sighed and opened their email; they began an email asking Prof. Smith to come and discuss the grade during office hours. Angel needed to know what they could do better for the next assignment.

A few days later, Angel sat with Prof. Smith in office hours.

Prof. Smith explained why Angel had earned the C-. She said Angel wasn’t writing in a way that was effective for scientists or for the purpose of the assignment. The sentences were too wordy, the writing style was not appropriate for scientific readers, some expected poster sections were missing, and the conclusion only summarized without making specific recommendations for the scientific community. Prof. Smith did not see the conventions she expected to see in scientific posters: a presentation of findings and data using relevant graphs or images, an evaluation of methods and processes, and specific recommendations based on data. Instead, she argued, Angel had written the poster as if it were an essay.

Angel was confused. Was the writing they had done in their composition class less good than the writing they were doing now?

“Not less good,” Prof. Smith said, “but different in its purpose, audience, style, and form.”

Prof. Smith then asked Angel what they had done to prepare for the assignment: Had they looked at example scientific posters? Had they researched scientific writing styles? Had they arranged to meet with another classmate to look over drafts? Had they taken their writing to the writing center for feedback? Prof. Smith had talked about these steps when the poster assignment was introduced. Angel struggled to remember that class day—it was a long day, and they had felt overloaded with all the information they had received. Together Prof. Smith and Angel logged into Canvas, their course learning management system, and located the course syllabus. They downloaded and opened the file—Angel was guilty that they hadn’t thought to do that while completing the poster. Sure enough, there was a section of the syllabus devoted to resources on scientific writing (Kinsley’s 2009 A Student Handbook for Writing in Biology, 3rd edition and Weaver et al.’s Scientific Posters: A Learner’s Guide) and even links to example scientific posters by former students.

Angel had used writing strategies that had worked well for them in the past: they had participated in class activities and done every bit of the homework. When they were ready to start the poster, they had outlined their ideas into sections, written in complete and engaging sentences, and cited their sources in MLA. They had moved their written sections onto a poster and added a visual. However, they hadn’t done enough to consider this new writing context, its new expectations, and the more independent responsibility they would have to take on as a writer. Being asked to write in new forms for new audiences demanded Angel adapt their writing strategies.

Before we move on, let’s look at the posters created by Angel and Akleelah. What differences do you notice? Table 1 summarizes several differences as well.

This poster has a lengthy introduction with an attention grabber to start. The research and lab work section discusses the student’s experience in the lab, not the scientific methods or lab processes. The conclusion offers a quick summary of the points already explored. Research is cited in MLA format, and the only visual is a microbe cartoon.

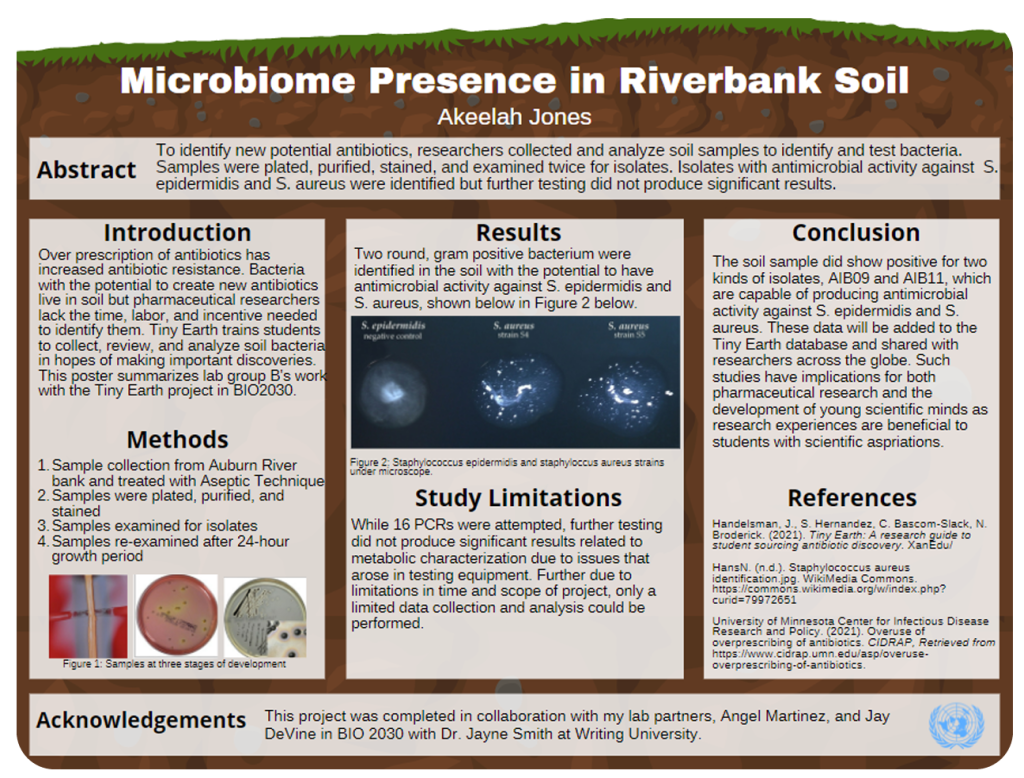

This poster starts with an abstract. Its introduction is short, offering brief context for the project. The methods are a simple list that focuses on scientific lab processes and includes a figure showing the three stages of development. The results also include a single takeaway with an image showing the antimicrobial activity in its microscopic form. There is a section on limitations. The conclusion offers a brief summary and calls for the Tiny Earth project to be continued to promote pharmaceutical research among young scientists. References are in APA format.

| Angel’s Poster | Akeelah’s Poster | |

| Style/ Word Choice | Uses “I” language, narrative style, and lengthy transitions to elaborate on the topic. MLA format | Uses more concise scientific language with tightly focused paragraphs. APA format |

| Organization | Emphasizes the introduction and conclusion sections as being the most important while methods focus on what they gained from engaging in research | Mirrors the IMRAD structure with methods detailing lab procedures |

| Design | Mostly written text with a single cartoonish graphic | Balanced between concise writing and visuals, including labeled figures |

Angel’s challenge isn’t uncommon for students as they move into their discipline-specific courses (also called courses in the major). Angel’s composition professor had taught them the importance of audience, purpose, and genre, and they had been successful applying those concepts in their composition course. However, it was more difficult for Angel to apply those concepts and manage their writing process in this new discipline-specific course. Prof. Smith expected Angel to do the work of learning about writing within the scientific community and the genre of a scientific poster more independently. Prof. Smith also didn’t provide checkpoints in draft development like Angel’s composition professor had, making it easy for Angel to wait to begin the project until just before it was due.

This chapter will help you understand how you can use the rhetorical concepts you learned in your composition course to decode new writing situations and genres that you’ll likely encounter in your upper-level, discipline-specific courses in your major. You might assume that writing is just writing, but Angel’s scientific poster shows that is not the case. While you might receive more support in your discipline-specific courses than Prof. Smith provided in the example, you will be expected to be more independent as you develop and revise your writing projects. You also could be expected to learn about disciplinary writing styles and genre conventions by seeking out resources on your own.

Discipline-Specific Courses and Discourse Communities

In Volume 3 of Writing Spaces, Dan Melzer helps readers learn about discourse communities, which are named so because they have specific communal expectations related to speaking and writing. Your majors represent discourse communities created by individuals within your discipline and future profession: biologists, nutritionists, professional writers, athletic trainers, hospitality professionals, nurses, and engineers are all different discourse communities.

When you begin taking courses in your major, your professors (who are members of those discourse communities), will develop assignments that help you to practice speaking and writing like members of those discourse communities. To do this, you will need to learn writing styles and genres that are popular in those discourse communities, although this purpose may not be formally explained in class.

Professors may not unpack discourse community expectations clearly, or they might expect you to do more independent work learning about writing style and format.

Mary Soliday notes that attempting new genres can be difficult and “disorienting,” even for professionals, because you are juggling a lot of newness all at once—“exploring new subject matter, trying on new roles, and meeting unknown audiences” (14). However, you can use the rhetorical concepts you have learned in your composition course to investigate writing in these new situations. And you are more likely to do this successfully when you have opportunity to engage in “bridging practices” to reflect on how your learning in composition can be framed to transfer to a new context (Rounsaville).

Take our issue at hand—the presence of microbiomes in soil. Different discourse communities would approach writing on this topic in different ways, using different formats. A biologist interested in the systematic study of these microbiomes will engage in research projects to collect and analyze soil samples, and share those analytical findings in scientific forms of communication, like a research poster, presentation, or article. A nurse, however, would focus more on educating individuals so that they avoid coming into contact with infection-causing bacteria. Because the nurse has a different purpose and audience, they would produce a genre focused on the general reader, like an informational health pamphlet or newspaper editorial. The writing styles of the biologist and nurse also differ because of their different audiences and purposes, even though they both study within the sciences.

The rest of this chapter will help you develop strategies for using rhetorical concepts (key terms like audience, purpose, rhetoric, genre, and conventions) to decode or investigate discipline-specific writing situations. The section below defines these common rhetorical concepts and explains why these concepts are relevant in your discipline-specific courses. The chapter ends with another scenario: one that shows Angel using the knowledge in the chapter to do better on their poster assignment.

Important Concepts and Definitions

Each rhetorical concept below has a general definition alongside how the concept might be applied in your discipline-specific courses. These terms give us a language to talk about our writing choices and transfer existing writing knowledge to new contexts (Rounsaville 12).

Purpose

Every communicative act has a purpose, or an impact you would like your writing to have on your audience. In Angel’s case, their scientific poster was intended to communicate a research experience and its findings to other scientists. Your purpose can be affected by other situational details, like the topic, audience, and genre. Similarly, your purpose can impact your writing style and word choice (i.e., are you writing to inform, persuade, call to action?).

Applying Purpose to New Writing Situations

The purpose of writing in your discipline-specific courses might not always be clear through assignment sheets. For example, scientific posters communicate a research project—its goal, methods, data, key findings, and implications—in a highly visual and easy-to-read fashion. When creating a poster, you need to consider visual design and how your photos, graphs, and tables from the research can support concise writing. Too much writing, and you lose the visual appeal of the scientific poster genre. Too many visuals and the audience does not have enough information to know how to interpret and connect the visual elements.

Consider how Angel and Akeelah each used visuals in their poster examples: Angel included a single, cartoonish visual while Akeelah included several labeled figures from her lab research. It’s appropriate for you to ask your professor to explain the single or multiple purposes of an assignment, either during class, in an email, or during office hours. You might say something like, “I know that there should be a specific purpose this writing assignment aims to achieve. Can you help me understand it?”

Audience

The people you are writing to engage, which in turns affects your writing style, format, and choices. When writing for an audience, you will want to consider their shared experiences and needs and write with those details in mind.

Applying Audience to New Writing Situations

Your audience can vary widely depending on the assignment. A good first question to ask is if your audience will be other experts in your discipline. To revisit our example, scientific posters can differ by their audience. Expert audiences will expect to see methods and terminology that show you are also an expert in their field and that your research project meets rigorous research expectations. If you are writing to other experts in your profession, you can use more technical language and assume a certain level of background knowledge. General audiences care more about the larger implications your research has on the general public, but they may need your help understanding the scientific concepts and terms. If your audience is not in your professional community, you will need to write using language and a style that is approachable to someone who does not have background knowledge in your discipline.

Rhetoric

The words, images, media, sounds, and body language you use to communicate your purpose to your audience. Choose rhetoric that will be effective and meaningful for your audience.

Applying Rhetoric to New Writing Situations

Rhetoric in your disciplinary communities includes more than written words: graphics, figures, and design (e.g., section headings, font size, color choice, layout) also hold value. You’ll want to remember this as you are investigating new genres. For example, when viewing a scientific poster, you’ll want to pay attention to how visuals like graphics and figures are used to communicate data as well as how design helps make the complex scientific topic being discussed more approachable to the audience. Further, when presenting your poster, your body language and oral delivery can be as influential as your word choice and poster design in helping your audience understand your research.

Genre

Most people think about genres that appear on their Netflix account: action, drama, documentary. But in writing, genres are different forms of writing. These formats have come to exist over time as individuals responded to the same rhetorical situation and needed to solve recurring communication problems. For instance, a resume is a particular genre that quickly tells an employer about your qualifications and background before the interview stage of hiring. You write a resume for a specific audience to achieve a particular purpose, persuading them to offer you an interview or job. Resumes help employers solve a problem: how can they review every applicant without expending too much time or labor?

While genres do not have concrete rules, they do contain conventions related to their structure, organization, language, and style (Miller 163). My use of in-text citations throughout this chapter is a genre convention that has come to be associated with forms of academic writing: I am expected to link my thought and ideas to existing scholars on a topic. So, as I discuss genre, I cite Carolyn Miller’s foundational text on how genres perform social actions, but I paraphrase Miller’s point so that her ideas are more accessible to my chapter’s audience.

Applying Genre to New Writing Situations

Inevitably, you will encounter new genres in your discipline-specific courses: lab reports, presentations, memos, posters, case studies. It is important to ask questions and learn about new genres as they represent ways that professionals in your discourse community communicate with one another. The first time you complete a writing assignment in a new genre, it is common to struggle and want additional support. As you develop drafts of these assignments, seek out models of successful examples, feedback from peers and experts in your discipline (like your professor), and writing about the genre, which may exist within your professional community (for an example, see Andrea Gilpin and Patricia Patchet-Golubev’s A Guide to Writing in the Sciences or Suzan Last’s Technical Writing Essentials: Introduction to Professional Communications in the Technical Fields). Prof. Smith included some of these resources in her syllabus, but Angel had forgotten about them. You may want to refer to course documents, like the syllabus, or other institutional resources, like subject-librarians.

Conventions

The characteristics that an audience associates with a particular genre and thus expects to see. These conventions can relate to the writing’s purpose, content, structure, organization, style, tone, language, and formatting.

Applying Conventions to New Writing Situations

As you encounter new genres, you should ask what conventions are associated with each genre. When attempting to write in a new genre, you want to be aware of conventions because your audience will expect to see them. These might be (but are not always) described in the assignment sheet. They should be observable in successful examples of the genre, so look for models of the genre in which you are writing. Ask questions about what writing in these genres typically looks like and does and seek out examples when you can.

Conventions can vary because of your audience, discipline, or culture. For instance, the conventions associated with a research poster can vary across disciplines: a research poster you create in a biology course may have different conventions than a research poster you create in a history course. While both will still purposefully communicate research, biologists expect concise informative writing, a straightforward design, and want to see scientific methods, while historians allow for more creative design with persuasive moments in writing and research methods drawn from the humanities. Conventions can vary across cultures and national contexts, too. Poster conventions that are typical for American professionals might differ from posters that those in the same profession in Japan or Ghana create because different cultures appreciate different aesthetic designs and have different ways to logically make meaning.

Writers do sometimes purposefully reject conventions because they want to challenge the expected to impact the audience. You should always deviate from conventions intentionally. Because conventions come to be expected by your audience, deviating from them might leave your audience confused or questioning your expertise. For instance, a biologist presenting their scientific poster to an audience of high schoolers might reduce their technical terms and play with a more colorful, creative design. Departing from conventions in this case makes the information more accessible and appealing to the biologist’s audience and helps the biologist achieve their purpose: to engage high schoolers in learning about biology research.

| RHETORICAL CONCEPT | DEFINITION | GUIDING QUESTIONS |

| Purpose | An impact you would like your writing to have on your audience (e.g., inform, persuade, call to act). |

|

| Audience | The people you are writing to engage, which in turns affects your writing style, format, and choices. When writing for an audience, you will want to consider their shared experiences and needs. |

|

| Rhetoric | The words, images, media, sounds, and body language you use to communicate your purpose to your audience. |

|

| Genre | Different forms of writing that have come to exist because they solve communication problems. Because genres recur, audiences come to expect to see certain genre conventions. |

|

| Genre Conventions | The characteristics that an audience associates with a particular genre and thus expects to see. These conventions can relate to the writing’s purpose, content, structure, organization, style, tone, language, and formatting. |

|

Strategies for Approaching New Writing Situations in Your Discipline

This section will lead you through strategies that can help you intentionally apply these rhetorical concepts in new writing situations. Before you begin writing,

- Carefully examine materials, like assignment sheets and rubrics. Pay attention to the purpose in the prompt (it can usually be identified through the verbs that are used, like “justify,” “reflect,” “analyze,” “research”). Nelms and Dively remind us that these verbs can take on different meanings across the disciplines: “research” might imply reviewing library sources in a writing course but might refer to data collected in a lab setting in science courses (227). When unclear, you should ask professors for examples and further explanation.

- Identify each rhetorical concept for the assignment and check that what you’ve identified matches what the professor is requiring.

- Genre matters! Ask experts to talk to you about genre conventions. If possible, locate examples of this genre from within your discipline and analyze the rhetorical moves that the writer is making. Then, reflect on the rhetorical choices you made in your draft and why you made them. Consider how you would justify why you wrote the project in this way if asked.

- Locate resources related to writing in your discipline, like examples and guidebooks. Seek out feedback from your peers in the course, professor, subject-librarians, TAs, writing center tutors, among others.

- Make a plan: when will you begin the project, how will you get feedback, and what resources will you draw from when you have questions? Give yourself time to engage in a writing process. This means you’ll need to start a project when it’s introduced to have ample time to revise higher-order elements like organization and structure as well as lower-order elements like sentence-level clarity, consistency in language, and proofreading.

After doing this work, I would still recommend visiting your professor during office hours to confirm that what you’ve found aligns with their expectations for the assignment. Coming to office hours with questions that have emerged from this investigatory process will show your initiative as a student while also ensuring you meet expectations. Remember, joining a discipline takes time. Don’t be discouraged if you struggle at first. Being able to use feedback to grow and learn will help you gain the disciplinary expertise that you need to feel more confident as a writer in this new space.

Applying These Strategies to a Scenario

Let’s revisit Angel’s story again. This time, consider what you would do if you were in their position:

In BIO 2030, Prof. Smith, introduced a new assignment, a scientific poster. The assignment prompt asks students to communicate the research they’ve been doing in their labs to a scientific audience. The assignment will be due in one month but will not be worked on during the class although some of the readings and lectures might be relevant to the assignment. What should Angel do next? Help them consider the important questions they should ask as well as what resources they can locate to help them begin their project.

What Might Angel Do Next?

I hope you had some sensible advice for Angel this time around. For one, they should begin by seeing if there is an extended assignment sheet or rubric that they can reference to get more information on the purpose, audience, genre, and conventions. They should also look back to the course syllabus to see if additional writing resources are listed there.

Next, they can locate resources and examples on scientific posters in biology. Once they feel they have a sense of what Prof. Smith might be expecting in this assignment, Angel could email her or visit office hours to make sure they are meeting her expectations. In this meeting, they should bring their resources and talk through them, showing Prof. Smith that they have done some initial research and found good examples to build from. This is a good point in the process for Prof. Smith to let Angel know if they are missing key assignment expectations.

After Angel is confident, they can create a first draft and get feedback. Ideally, they should find someone familiar with scientific writing, like a peer in Biology or a writing center consultant with a background in STEM writing. Angel shouldn’t rely on friends without experience with scientific writing as their English major friend will likely be using different writing conventions than their professor expects. This feedback will help Angel know if what they are intending to communicate is coming across clearly to a real reader. As they revise, Angel could continue to use the resources they found, the assignment materials, and additional opportunities for feedback.

Aside from potentially doing better on the assignment, Angel will feel more confident as a writer in biology. Also, Angel will engage in important strategies that are necessary to developing writing: considering genre and context, embracing the writing process, and integrating feedback. These steps are taken by all writers—even writers who are experienced with their professional community and its expectations.

Conclusion

While you have established a solid foundation through your composition course, all students, new professionals, even experts continue to learn about writing well beyond composition.

I hold multiple graduate degrees in English and participate in a discipline with others who study and teach writing. Despite our expertise in writing studies, even we frequently commiserate that writing is a taxing and troublesome act.

When you are adapting to discipline-specific writing, those challenges are heightened, and sometimes you might even experience failure in your initial attempts to write something new. Those feelings of confusion that might be overwhelming at first are very normal experiences! If you take the time to evaluate each new writing situation and apply the rhetorical concepts you have learned, you can transfer your writing habits and take advantage of available resources. I hope these tips prepare you to anticipate new writing challenges and give you some strategies for tackling them.

Note

Thank you to Noah Flood, a talented peer consultant in Auburn University’s Miller Writing Center, for his feedback on this chapter.

Works Cited

Bunn, Mike. “How to Read Like a Writer.” Writing Spaces, Vol. 2. Parlor Press and WAC Clearinghouse, 2011, pp. 71–86. Retrieved from https://writingspaces.org/sites/default/files/bunn–how-to-read.pdf

Gilpin, Andrea and Patricia Patchet-Golubev. A Guide to Writing in the Sciences. University of Toronto Press, 2000.

Kinsley, Karin. A Student Handbook for Writing in Biology, 3rd edition. Sinauer Associates, Inc. and W.H. Freeman and Co, 2009.

Last, Suzan. Technical Writing Essentials: Introduction to Professional Communications in the Technical Fields. British Columbia/Yukon Open Authoring Platform, 2021. Retrieved from https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/.

Melzer, Dan. “Understanding Discourse Communities.” Writing Spaces. Vol. 3. Parlor Press and WAC Clearinghouse, 2020, pp.100–115. Retrieved from https://writingspaces.org/sites/default/files/melzer-understanding-discourse-communities.pdf.

Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre as Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 70, 1984, pp.151–167.

Nelms, Gerald and Ronda Leathers Dively. “Perceived Roadblocks to Transferring Knowledge from First-Year Composition to Writing-Intensive Major Courses: A Pilot Study.” WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 31, no. 1–2, Fall 2007, pp. 214–240.

Rounsaville, Angela. “Selecting Genres for Transfer: The Role of Uptake in Students’ Antecedent Genre Knowledge.” Composition Forum, vol. 26, Fall 2012, pp. 1–16.

Soliday, Mary. Everyday Genres: Writing Assignments across the Disciplines. Southern Illinois University Press, 2011.

Weaver, Ella, Kylienne A. Shaul, Henry Griffy, and Brian H. Lower. Scientific Posters: A Learner’s Guide. National Science Foundation and The Ohio State University, n.d., https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/scientificposterguide/. Accessed 1 April 2022.

*This article originally appeared in Writing Spaces Volume 5 and can be viewed here in its original format.