Changing Your Mindset About Revision

L. Lennie Irvin

Introduction

What has revision got to do with building a rocket? A lot, it so happens. Perhaps you’ve seen the video about SpaceX’s long drama to develop a rocket that lands successfully. Called “How Not to Land an Orbital Rocket Booster” and accompanied by the theme music from Monty Python’s Flying Circus, the video shows rocket after rocket crashing and blowing apart: one blows up in mid-air, another lands too hard and explodes, and more land but then tip over into a billowing fireball. Finally, the video shows the first rocket boosters that land successfully. Since that date in 2005, SpaceX has successfully landed its rocket boosters over 200 times (as of 2023). Though writing and revising your college essay, of course, differs from building a rocket (despite sometimes feeling as hard), the process and concepts that drive that process are similar.

Writing is a developmental process in which we discover what we mean to say and how we actually say it as we work on and rework a piece of writing.

We can’t expect writing one draft and polishing it up will produce dazzling insights, convincing arguments, and error-free writing just as Elon Musk didn’t expect to land his rocket on the first try. Producing a successful piece of writing takes multiple drafts, like SpaceX had to keep building and testing new versions of its rocket after each failure. Revision, it turns out, is about discovery, and growth, and problem-solving.

The prospect of revising your writing may seem about as exciting as going to the dentist, but I invite you to keep an open mind and listen to what I have to share about revision.

The heart of your growth as a writer depends upon developing your capacity to revise your writing.

But revision is not easy. As a once clueless first-year writer myself, and now as a writing teacher with 30 years of experience, I have seen firsthand how difficult revision is. Much has been written about the terror of the blank page, but little attention has been given to the writer’s block of revision. I can’t promise that reading this essay will magically transform you into a master of revision, but I invite you to keep reading because what I share will help you become a better reviser and writer.

So what is this secret to revision I have to share? It’s simple and it turns out not so secret: for you to become a better reviser of your own writing, you must change your thinking about revision and writing. In fact, research into the difference between “revisers” who made substantial changes to their writing and “non-revisers” who only made surface changes found the most important thing students can learn to improve is to develop new mental models of the revision process (Beach 164). You need new concepts of what revision is and what it entails to be a better reviser.

Before we explore what this new concept of revision is, we need to dispel false concepts about writing and revision that hinder writers before we replace them with a new, more helpful model. Below are some of the flawed attitudes and concepts about revision and writing I suffered from as a first-year writer and see commonly in my students that I believe hinder revision success. Perhaps you will relate?

Flawed Concepts About Writing and Revision

Writing Is About Getting It Down

Sometimes called the transmission or “knowledge telling” model of writing, this belief sees writing in terms of speaking—we say what we have to say, and we are done. Writing is a one-way delivery system of packaging our thoughts and sending them onto the page. With this view, “one-shot drafts” are the norm. I’ve said what I want to say—what else is there? Years of writing essays in one sitting at the last minute or for standardized tests also may have reinforced this view of writing.

Revision Means Tidying Up at the End

Following from the “getting it down” model, the next step after you get it down is to clean it up. You’ve formed the package in your head and painstakingly spit it out on to the page—now that you’ve got it all down, the most important thing to focus on is correcting errors and wording. Because all the real work getting the writing down is done, revision occurs at the end of the writing process and is reduced to editing and proofreading.

The Most Important Thing About Writing Is Grammar

The “revision means tidying up” model makes sense when we believe grammar is king when it comes to writing. Grammar seems to be the most important thing your teacher wants—right? Years of teachers grading your writing mostly on the basis of grammar may have taught you that. Revision should focus on grammar because grammar is what matters most.

Some of you may be nodding in agreement with these beliefs about writing and revision. They may even seem correct because you’ve depended upon them to write for years. However, for you to become a better reviser of your own writing, you will need to change your thinking about revision and writing. You need to develop a new mindset about revision.

The Importance of Concepts as Mindsets

Before presenting you with different models of writing and revision, I want to talk about the importance of concepts for your development as a writer (and an individual who is learning and growing). Concepts, you say? That’s pretty abstract. Don’t I need to know rules and skills? Yes, knowing rules and skills are important, but concepts are the big picture mental frameworks within which we understand and apply rules and skills. Concepts are ideas or mental models we have about the world. These mental models are created and sustained by our beliefs, our theories, our experience, as well as our premises, assumptions, and values. Whether we perceive a concept as truth or opinion, it expresses an idea about something that serves us as knowledge and underpins our thoughts and actions. For example, to say writing is a process may seem like a factual statement, but in reality it is a concept built upon beliefs and theories about how writing happens.

Researchers into concepts have identified two significant aspects about the nature of concepts:

Concepts are like portals to new learning (these are called “threshold concepts”).

Concepts are like ships that enable you to carry learning from one context to another (these are called “transfer concepts”).

Jan Meyer and Ray Land describe threshold concepts as representing “a transformed way of understanding, or interpreting, or viewing something without which the learner cannot progress. As a consequence of comprehending a threshold concept there may thus be a transformed internal view of subject matter, subject landscape, or even world view” (“Linkage to Ways of Thinking” 412). Transfer concepts signify knowledge and perspectives that are easy for learners to generalize and apply in a new context, even though it is different. Writing scholars Kathleen Blake Yancey, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak have developed a teach-for-transfer writing curriculum built around “key terms students think with, write with, and reflect with reiteratively during the semester” (5). “Rhetorical situation” is one term they explore as a transfer concept. These key terms represent concepts that enable writers to take what they learn about writing in their first-year writing class and use it in future writing situations.

So what are better concepts about writing and revision than the misconceptions listed above? How will they work as new and improved ways of thinking about writing that will help you revise your papers better and more confidently now and in the future? I’m going to give you one big threshold concept about revision, but like one of those Russian nesting dolls, you’ll find other related concepts nested inside this larger one. I think you will find this concept both basic and profound.

Writing Is an Inquiry Process

Writing is not just about getting it down; writing is a process of inquiry. Certainly, we do a lot of writing that resembles speech where we express ourselves and move on. This type of writing might be an email, social media post, or even a journal entry. You may even do this kind of one-shot writing in your college classes with discussion posts, peer response, or essay exams. This kind of “telling” writing is about getting down what you think in the moment. Once you tell what you have to say, you might (or might not) review it for clarity and small errors. Then you’re done. That’s the “revision is about tidying up at the end” misconception.

But not all writing is simply about knowledge telling, especially in college. Whenever you write something like an essay, a scholarship application, or a report, you are being asked to do something more. Doug Downs and Liane Robertson make this point about writing when they say, “writing is more than transmitting existing information, it is instead a means of creating new knowledge” (108).

Writing is a “knowledge-making” activity: we discover what we mean as we write it.

I want you to sit with that statement for a while and absorb it because as radical as it may seem, I know you have experienced this truth about writing in your past. When we begin to write, we don’t have everything figured out, and as we write, what we mean to say grows, changes and becomes clearer. We discover what we mean as we write it. And this discovery happens not just while we write, but between drafts when we revise.

Ann Berthoff echoes this belief about writing when she states: “Composing […] is a means of discovering what we want to say, as well as being the saying of it. […] It is a process of discovery and interpretation, of naming and stating, of seeing relationships and making meanings” (20). To say writing is a knowledge-making, inquiry process is to say writing is a thinking process founded on revision—as we write we discover, we think and rethink, we write and rewrite. Because language and thought are so connected, as our thinking evolves, so too does our text, and as our text evolves, so too does our thinking. When we engage in this messy inquiry process, we both push our thinking farther and end with a better finished text.

The Problem with “One-Shot” Drafts: Rethink Drafting

You may have mastered one-draft writing because you’ve been trained to write in this way through years of school and standardized tests. In this model, you figure out what you want to say, write it down, and then review it once for errors. Then you’re done. Even if writing the initial draft is a long painful ordeal over many sittings with stops and starts, once the draft is down it’s done. I call this the 3-D printing model of writing: the finished text exists in our head like a computer program, and we just hit print and the exact object in our head is reproduced on the page line by line.

The problem with this model for writing is it shortcuts the growth of our thinking. Plus, it ignores this truth about writing—first drafts are always “rough.” What we say on the page never matches what we mean in our head, nor does it exactly fit the writing situation. The pressure to write perfectly in a first attempt is simply unreasonable: it’s like expecting a batter to hit a home run every time they bat.

Dave Anish and David Russell believe even the term “draft” may be a source of confusion regarding revision for students today. The term “draft” comes from the age of print when we live today in a world of word processing. In their research, they found few students saw draft to mean “iterative,” as in multiple versions, but instead saw draft to mean something more fixed and final (Anish and Russell 408). In our age of computers, we are more familiar with the term “version” than “draft.” For example, Windows 11 is a version of Windows, and video game companies release beta versions of their game hoping players will find flaws and give feedback before the official release. Although the term “draft” is not going away in common usage, I want you to think “version” when you hear the term “draft.”

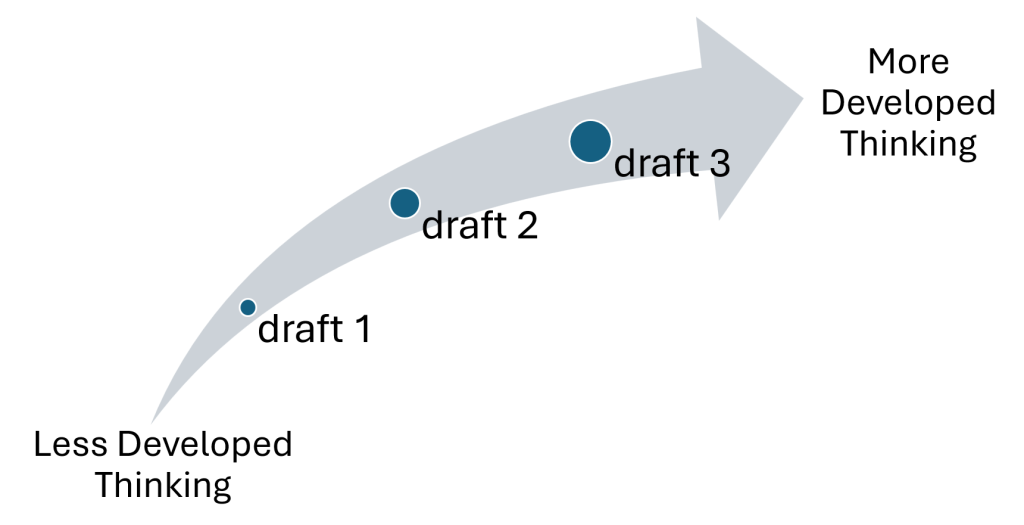

Your drafts are versions of your paper, and the truth is it takes multiple versions to reach a good final copy of your essay. You can’t expect to land a rocket on your first try.

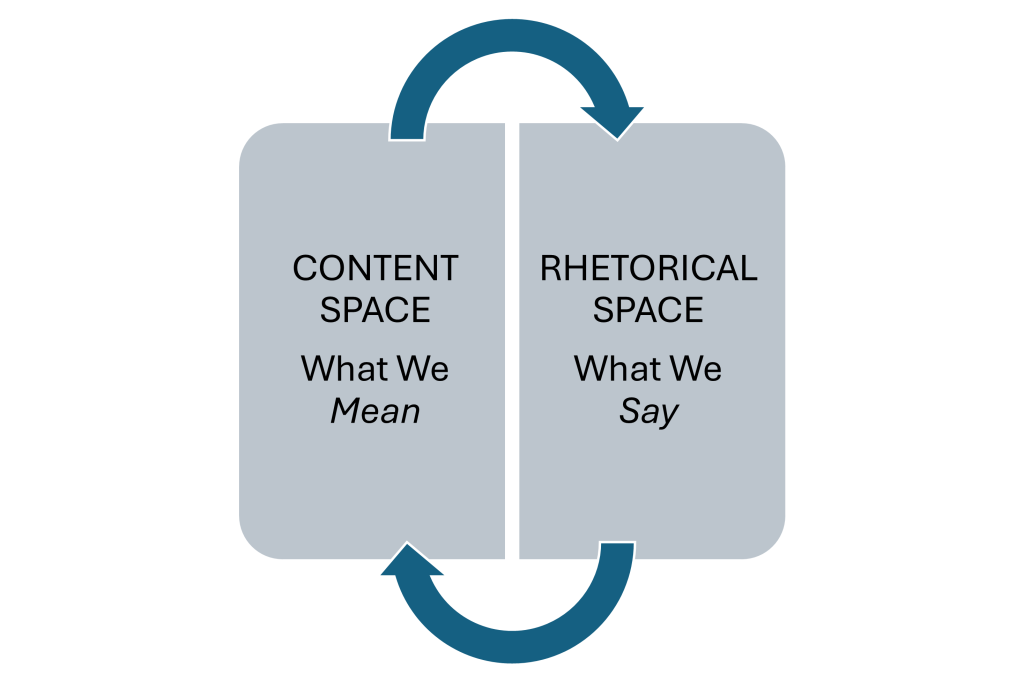

Now let me dig in a bit deeper into why your first version should never be your final version, and why a clean-up of your first version is not enough. The difficulty of writing and why we never write perfect first drafts is found in the simple truth that there is a difference between what we mean and what we say in writing. Researchers Carl Bereiter and Marlene Scardamalia described two spaces writers negotiate as they compose: what we mean (the Content Space which represents the thinking and meaning in the writer’s head) and what we say (the Rhetorical Space which represents the words on the page) (302-303). The miracle of writing and language is that we are able to transfer what we think and feel inside our consciousness and put it into little black marks on a white page.

When we believe writing is just a matter of getting it down in a one-shot draft, we mistake that we can perfectly (or adequately) get down what we mean on the page in one draft. That’s the myth of the 3-D Printing model of writing. But we all know writing does not operate this way. We always experience a gap between what we mean and what we say.

A big step then in appreciating the need for revision is to acknowledge (and respect) this fundamental truth about writing: writing is about getting our thinking and meaning on the page, and there will always be a divergence between what we mean in our head and what we say on the page.

To say “writing is an inquiry process” means it is a developmental process in which we discover ways to get what we mean closer to what we say and what we say closer to what we mean.

Peter Elbow compares the writing process to filling a basin of clear water: “Producing writing, then, is not so much like filling a basin or pool once, but rather getting water to keep flowing through till it finally runs clear” (28). Elbow’s image of keeping the water flowing through the basin is this work of revision. Each time we work on a piece of writing, we bring what we mean and what we say more into convergence. Each time we review how well our current text is meeting the needs and requirements of the writing task and situation, we find something missing or out of alignment to adjust and fix. Through the work of revision, we get closer to our goal of a successful piece of communication.

The Problem with Tidying Up: Internal Revision and External Revision

Too often revision is believed to involve only the text on the page, but this ignores the importance of our thinking. As an inquiry process, the writing process involving multiple drafts is about the development of our thinking, particularly for college writing. Writing in college is about learning after all.

Donald Murray in his book The Craft of Revision talks about this connection of revision to our thinking: “When we revise we do not so much revise the page as revise our thinking, our feeling, our memory, ourselves—who we are” (1). In describing the relationship between what we mean and what we say, Murray develops two categories for revision: “internal revision” and “external revision.”

Internal revision happens in our head: it is about the change and growth of our thinking about the topic and our understanding of the writing task.

External revision happens on the page: it involves the change in our text and how it presents our thinking on the page.

With these ideas about revision, Murray suggests that a dynamic relationship exists between what we mean and what we say. As we internally revise our thinking about the topic and task, it influences our external revision of the text. Changing and developing our thinking should lead to changes and development in our text. Likewise, as we externally revise our text, we trigger internal revision to our thinking. In other words, what we mean always shapes what we say in writing, just as what we write constructs what we mean.

Perhaps you think I am stating the obvious, but recognizing that when you write you are negotiating these two spaces—what’s in your head and what’s on the page—can help you engage in productive revision. A simple guide for revision is to ask yourself these basic questions:

Is what I’ve written really what I mean?

Is what I mean what I’ve really written?

Understanding this concept helps you see that issues you identify in your writing may come from problems in your thinking. And as you develop and revise your thinking, you can use this re-thinking as your best guide for re-writing the text on the page.

I’ll close this section with a diagram to illustrate how revision is an inquiry process. It emphasizes these two points I’ve been making:

#1: Revision is about developing both our thinking and writing.

#2: Revision helps us get closer to saying in writing what we mean and appropriately meeting the writing situation.

Revision as Troublesome Knowledge

Truly acknowledging that writing is an inquiry process with revision hardwired into its DNA may be challenging to you. Meyer and Land talk about how threshold concepts prove to be “troublesome knowledge” for learners at first because once they grasp the concept—once they pass through the portal—there is no going back. Now that you see this connection between writing and thinking and the developmental nature of writing’s inquiry process, you can’t unsee it. Now that you see revision as the necessary step for growth and improvement in a text, doing a one-shot draft and tidying it up at the end seems insufficient, even absurd.

But accepting the truth of this concept is troublesome—particularly because it means you have to revise. Meyer and Land describe a liminal space as students grapple with a threshold concept where they feel not only unsettling but stuck (“Epistemological Considerations” 377–378). They emphasize the importance of teachers designing their curriculum to help students negotiate these transitions (386). With Meyer and Land’s imperative in mind, I am going to make some suggestions about how to approach writing as an inquiry process that I hope will assist developing your ideas and text through revision.

Revising Practices with Inquiry in Mind

Follow a Three-Draft Sequence to Write Your Papers

I want to suggest a sequence for your drafting of a piece of writing. While some writing pieces may take many more drafts, the three-draft sequence below can serve you well for college writing.

The Three-Draft Sequence

Version #1: The Get-It-Down Draft

Whether you painstakingly write your first draft over many days or dash off a freewriting draft in 30 minutes, consider this first version of your essay to be like a first sketch of your thinking on the topic. As you write and then consider your first draft, don’t focus on correctness or perfection. You may not even worry about proper organization or specific support. This draft can be rough and even incomplete. The main goal is to get down your thinking in as complete a draft text as you can. It’s too early to worry about the grammar or any other editing concerns!

Version #2: The Development Draft

As you move from first to second draft, your focus will be on developing your thinking and your text. In some classrooms, this development draft may be submitted to peers for feedback and in others to the instructor (or perhaps both). If the first draft is like a sketch, the second development draft is where you fill in the sketch with paint. It’s in this second version where you work on a clear expression of your thesis, seek to organize your writing clearly and logically, and try to include full support for your thesis. You also seek to fulfill the requirements of the writing task. But at this point, you are still not worried about correct grammar or documentation. You might call this version your first dress rehearsal of your final draft.

Version #3: The Final Draft

This final draft enables you to troubleshoot and improve your content (your approach to the writing task, thesis, organization, and support), but the focus for the final draft is on readability and careful editing and proofreading. You may do more than two drafts to get to this final draft, but at some point the paper is due and you will have to turn it in to be evaluated for a grade. Now this performance is going live before an audience, and you want to make it as good as you can.

To sum up, as you go from first draft to final draft, your focus for revision gradually shifts from internal revision (what you mean) to external revision (what you say), from a creative and generative phase to a more critical and evaluative phase. Allowing yourself the space and freedom to let your early drafts be rough and provisional without the high bar of being a final draft enables you to see and be open to the changes to content that represent the true growth of your thinking. But you have to let go being perfect in your first or even second draft.

Always Get Feedback

While reviewing your draft on your own is important, getting feedback to assist you with seeing what needs to be improved in your paper is crucial. Research has shown that peer feedback, especially when provided with a sense of the goals and standards of the writing task, is the best source for helping writers make higher order revisions to their writing (Zhang, Schunn, and Baikadi 699). It seems we need this outside perspective to help us see areas for improvement in our writing, especially big picture things about what we are trying to say and how we are saying it. Your class may engage in peer response on drafts, or your instructor may provide feedback for you, but even if you don’t get feedback in your class, you can seek out tutors or other readers to read and respond to your draft.

Reflect Between Drafts to Set Revision Goals

Between each draft and before starting to revise your essay for the next draft, take a few moments to reflect on your draft. I strongly recommend you do this self-review in writing: get out a pen and piece of paper or open a word processing document and write about where you are with the draft and where you think it needs to go. Review what you’ve written in terms of the feedback you’ve received and the goals of the writing task. Ask those key questions I mentioned earlier:

Is what I’ve written really what I mean?

Is what I mean what I’ve really written?

As you interrogate this relationship between the Rhetorical Space (what you written) and the Content Space (what you mean), keep foremost in your mind what success means for this piece of writing—both in terms of writing a successful essay according to the requirements of the writing task and in terms of saying what you mean and successfully accomplishing your purpose toward your reader (Irvin 18).

This internal understanding of your writing goals and what successfully reaching them looks like will help you identify areas for improvement in your draft. But they won’t help unless you have a good understanding of what successfully reaching these goals looks like. For example, you won’t be able to diagnose problems in your Introduction without a strong grasp of how to write an Introduction, especially a thesis statement. Likewise, you may not see issues in the formatting of your Works Cited page or know how to fix it unless you know what a successfully formatted Works Cited page looks like. You may need to review the learning materials or specifics of a writing task to be able to see issues in your draft and know how to address them.

The last step in this between-the-draft reflection is to make a plan for what to revise in the next draft. Focus on big picture things first like your thesis, the structure of your essay, the development of your ideas, and how well you are fulfilling the requirements of the writing task. Then use this plan to guide you as you revise your essay for the next draft.

Save Editing for Last (Really)

It takes something akin to an act of faith not to correct the grammar in your first or second drafts. Many of us are so conditioned to think our text must be perfect that we can feel extremely uncomfortable letting something we’ve written be messy and imperfect. As I mentioned in the three-draft sequence above, I urge you to embrace the messiness and flawed nature of early drafts. Let them be rough. Save the impulse you have for tidying up and perfecting the writing until you truly are at your final draft.

This means making editing a distinct activity in your writing process with the singular goal of readability at the sentence and word level. Print off a fresh copy of your draft, get out a pen, and go through your draft sentence by sentence, word by word. Read passages aloud to hear if they make sense. Look up any grammar rules or usage questions you have.

Only a Beginning

I hope you now have a new mindset when it comes to writing and revision. Re-vision is after all about “seeing again.” What I have shared with you is one key concept that will change the way you write and revise. Now that you see writing as an inquiry process, you understand revision is about developing your thinking and text over multiple versions of the essay. Revision is not easy, but it is gratifying work. Heck, it’s exciting—like landing a rocket on a drone ship in the middle of the ocean. And as we know by now, we don’t land a rocket on our first try.

Works Cited

Anish M., Dave and David R. Russell. “Drafting and Revision Using Word Processing by Undergraduate Student Writers: Changing Conceptions and Practices.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 44, no. 4, May 2010, pp. 406–434.

Beach, Richard. “Self-Evaluation Strategies of Extensive Revisers and Nonrevisers.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 27, no. 2, 1976, pp. 160–64.

Bereiter, Carl and Marlene Scardamalia. The Psychology of Written Composition. Hillsdale, N. J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1987.

Berthoff, Ann E. The Making of Meaning: Metaphors, Models, and Maxims for Writing Teachers. Boynton/Cook, 1981.

Downs, Doug and Liane Robertson. “Threshold Concepts in First-Year Composition.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth A. Wardle. Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 105–121.

Elbow, Peter. Writing Without Teachers. Oxford University Press, 2007.

“How Not to Land an Orbital Rocket Booster.” YouTube, uploaded by SpaceX. 14 Sept 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bvim4rsNHkQ.

Irvin, L. Lennie. Reflection between the Drafts. Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2020.

Meyer, Jan H., and Ray Land. “Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge (2): Epistemological Considerations and a Conceptual Framework for Teaching and Learning.” Higher Education, vol. 49, no. 3, 2005, pp. 373–388, doi: 10.1007/s10734-004-6779-5.

—. “Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge: Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practicing.” Improving Student Learning Theory and Practice – 10 Years on: Proceedings of the 2002 10TH International Symposium Improving Student Learning, edited by Chris Rust. Oxford Centre for Staff & Learning Development, 2003, pp. 412–424.

Murray, Donald M. The Craft of Revision, 3rd ed. Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1998.

—. “Internal Revision: A Process of Discovery.” Research on Composing: Points of Departure, edited by Charles R Cooper and Lee Odell. NCTE, 1978, pp. 85–104.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak. Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State University Press, 2014.

Zhang, Fuhui, Christian D. Schunn, and Alok Baikadi. “Charting the Routes to Revision: An Interplay of Writing Goals, Peer Comments, and Self-Reflections from Peer Reviews.” Instructional Science, vol. 45, no. 5, 2017, pp. 679–707, doi: 10.1007/s11251-017-9420-6.

*This article originally appeared in Writing Spaces Volume 5 and can be viewed here in its original format.