Jeffrey Becker

Temple of Vesta, The Roman Forum (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Eternal City

Rome is often described as the “eternal city,” conveying the idea that it lives (and has lived) forever, perhaps even suggesting a sort of unchanging immortality. However, even those things that are iconically eternal have a beginning. The humble beginnings of Rome provide the roots of a long cultural story, one that we continue to experience, sample, and live via archaeology, history, and cultural reception.

Romulus—Rome’s legendary founder—is said to have been suckled by a she-wolf, to have slain his own brother, and to have instituted the bellicose, strong, and independent character of the populus Romanus (“the Roman people”). The history and archaeology of the city that Romulus is credited with founding are inextricably wrapped up in layers of myth and folklore that helped Romans to tell their own story and generate collective memories in the urban space. For many archaeologists, these legends that describe the foundation of the city of Rome are fantastical and represent an attempt to explain not only how the city came to be founded, but also to establish ties between the city center and the surrounding areas of central Italy. The perspective offered by archaeological evidence allows us to examine the earliest phases of the city and the settlements that would have been founded there and to see the places in which myth and reality intersect. The legends and folklore also need testing, especially since blind acceptance of them has reinforced stereotypes about the city of Rome and its people that may not be representative of reality.

Model of Rome in the Archaic period with a view of the Capitol and the Forum (Musée de la Civilisation Romaine, Rome)

Legends aside, Rome’s earliest beginnings are humble and relatively ordinary. Settlements of smaller size that often occupy naturally defensible hilltops characterize the Iron Age in central Italy. Legends aside, Rome’s earliest beginnings are humble and relatively ordinary.

The Iron Age in central Italy is characterized by small settlements that often occupy naturally defensible hilltops. By the eighth century B.C.E., changes in settlement types became evident. These changes involve a reallocation of space and a movement toward nucleation—that is the clustering of population in a more densely populated center as opposed to a lower density scattering of small settlements across the landscape. In the immediate neighborhood of Rome, this is first evident in Latin settlements (for instance, near Gabii to the east of Rome), as well as in Etruscan settlements in south Etruria, for example Veii and Tarquinii.

Map showing Latin settlements in central Italy (and, toward the north, Etruscan sites in Southern Etruria) (map, Cassius Ahenobarbus, CC BY-SA 3.0)

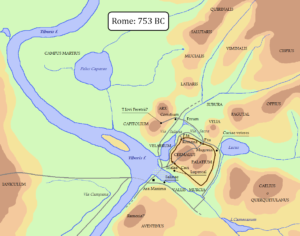

It is as a result of this phenomenon that the historical Rome comes into being. Today archaeologists often refer to “early Rome” as a way to describe the early phases of the city that correspond to the Iron Age. The legendary actions of Romulus were believed to have taken place in the year 753 B.C.E. As a result of Romulus’ actions, the Palatine Hill was thought to have been surrounded by a fortification wall. Archaeological investigation of the Palatine Hill itself has revealed important clues about the earliest days of the city of Rome, including traces of an early wall surrounding at least some part of the Palatine Hill. This wall may be referred to as the “wall of Romulus” or murus Romuli (and should not be confused with the later “Servian wall”).[1]

“The Palatine City” and the “Hut of Romulus”

The agglomeration of Iron Age huts on the Palatine Hill is representative of the type of settlement commonly found in central Tyrrhenian Italy during the early Iron Age—relatively small in size and taking advantage of naturally defensible positions. The typical Iron Age hut in central Italy is a one-room structure with an oval ground plan. Its roof is of thatching that is supported by a wooden roof tree while its walls are generally made from a technique called wattle-and-daub which is essentially mud plaster applied over a framework of organic material. These huts served multiple functions, including processing and storage. In addition to the examples known from the site of Rome, we can see evidence for similar building types among the Etruscans and the Latins. Some assistance in reconstructing the appearance of these huts is offered by contemporary cinerary urns that take the shape of a hut, earning them the moniker “hut urns”. These urns may represent the economic status of the deceased person.

Hut Urn, 8th century B.C.E., Etruscan, ceramics, 22 x 23 x 28 cm (The Walters Art Museum)

The Great Drain and the emergence of the Forum Romanum

The valley that is framed by the Palatine, Esquiline, and Capitoline hills (what we today call the Forum Romanum—the Roman Forum) was originally not a settlement area, but rather a space that lay outside of settlement limits.

Rome in 753 B.C.E. (map, Cristiano64, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The usability of this valley was compromised by the fact that periodic, seasonal flooding of the Tiber river, coupled with natural surface water, could render the valley wet and marshy. Since this area lay outside of settlement limits, it came to be used for both inhumation and cremation burials as was customary in the Iron Age. As Rome was beginning to coalesce, however, this space came to be of interest to the nascent city and its use was re-tasked. This meant that both human behavior and natural events had to be checked. For the former, human burials in the valley needed to cease, with burial activity being transferred to another location on the far side of the Esquiline Hill. Curbing nature was a larger challenge and it involved an impressive example of the early state organizing labor and resources to raise the surface level of the Forum valley through an artificial landfill project. This project involved the manual gathering and dumping of soil in the forum valley in order to raise the surface level by several meters. This would have required upwards of over 35,000 cubic feet of landfill to accomplish.

In connection with the landfill project was the creation of a channelized drain dubbed the Cloaca Maxima (“great drain”) that drained water away from the valley, through the area of the Velabrum, to the Tiber river. While initially an open drain, the Cloaca Maxima was eventually covered by vaulted masonry.

The poliadic temple—Jupiter Best and Greatest

The chief deity of the Roman people is the sky god Jupiter whose cult is connected in the legendary history with the earliest days of Rome. By the later sixth century B.C.E. a massive building project organized by the last of Rome’s Archaic kings was taking shape, namely creating a chief civic temple dedicated to IUPPITER OPTIMUS MAXIMUS or “Jupiter Best and Greatest.” Perched atop the Capitoline Hill, the temple of Jupiter would remain the focus of the Roman state religion for a millennium to come. Sacro-civic architecture of this type draws on central Italian architectural models and, in terms of urban life, provides a focused location for key events of the state’s ritual activity.

Left: reconstruction (in plexiglass) of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus revealing the foundations below, which can be seen today in the Capitoline Museum (right).

The river harbor and the “Cattle market”

Another important area of activity in the early city is the area surrounding the river harbor on the Tiber River, a space usually referred to as the Forum Boarium (“Cattle market”). The harbor provided a place where river-borne craft could put-in to shore in order to engage in commerce. Archaeological evidence suggests that this area is early on a focus of regional economic interchange and it takes advantage of a key point on the Tiber river, given that this is one of the only natural fords or crossing points in the lower extent of the river.

Reconstruction of the imperial Rome (4th century C.E.), by Italo Gismondi (photo: Sebastià Giralt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The twin temples in the archaeological site today known as the “Sacred Area of Sant’Omobono” is connected with the commercial function of this zone. Its roofline decorations included a terracotta statue of Herakles who was connected legendarily to the area of the Forum Boarium and also served as patron of travelers and traders. Dedications at the twin temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta reflect the nature of this area as a place of commerce and interchange. Like the Capitoline temple of Jupiter, these temples draw on central Italic traditions in terms of their architecture.

The foundations of the city and its growth in the Archaic period set the stage for its next phase. Tradition holds that Rome expelled her Archaic kings in 509 B.C.E., ushering in a period when a reshuffling of governmental structures would create a republican system. This new system of government also brought with it implications for the development of the city of Rome and the role played by art and architecture.

Notes

1. See T.P. Wiseman, “Review: Reading Carandini,” The Journal of Roman Studies 91 (2001) pp. 182-193; Roberto Suro, “Newly Found Wall May Give Clue To Origin of Rome, Scientist Says: When Did Rome Become Rome? Wall May Give Clue,” The New York Times (10 June 1988), p. A1; Henry R. Hurst, “The ‘Murus Romuli’ at the Northern Corner of the Palatine and the Porta Romanula : a Progress Report,” in Res Bene Gestae: ricerche di storia urbana su Roma antica in onore di Eva Margareta Steinby, edited by Anna Leone et al, pp. 79-102 (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 2007); Andrea Carandini et al. The Atlas of Ancient Rome: Biography and Portraits of the City 2 volumes (Princeton University Press, 2017). Table 62.

Additional Resources

Capitoline Museums – via Google Arts and Culture

Albert J. Ammerman, “On the Origins of the Forum Romanum,” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 94, no. 4, 1990, pp. 627-645. http://www.jstor.org/stable/505123

Andrea Carandini et al. The Atlas of Ancient Rome: Biography and Portraits of the City 2 v. (Princeton University Press, 2017).

Isabella Damiani, Claudio Parisi Presicce (eds.), La Roma dei Re: Il racconto dell’archeologia (Gangemi Editore, 2019).

Alexandre Grandazzi, The Foundation of Rome: Myth and History, trans. Jane Marie Todd (Cornell University Press, 1997).

John N. Hopkins, The Genesis of Roman Architecture (New Haven: Yales University Press, 2016).

C. J. Smith, Early Rome and Latium: Economy and Society c. 1000 to 500 BC. (Oxford University Press, 1996).