Accounts of the Sack of Rome

In 410 C.E., Rome was sacked by Visigoths under the leadership of Alaric. This was the first time in close to 800 years that the city fell to a foreign enemy, though she had sometimes been divided by civil war. At this point, Rome was no longer the official capital city of the Western Empire, but it was still an important center for Christianity and Roman culture. While the Western Empire would continue under the leader of a Western Emperor until 476 C.E., the immediate consequence of the sack of Rome was to divide the city’s Christian and Pagan communities even further. Both sides viewed the event as bolstering their claims of divine support. For pagans, the calamity happened because the people had turned away from the old gods. For Christians, it was due to their sins. Setting religious differences aside, the sack of the city was also a tremendous blow to Rome’s image as a tower of civilization that had subdued the barbarian lands surrounding it – or was it?

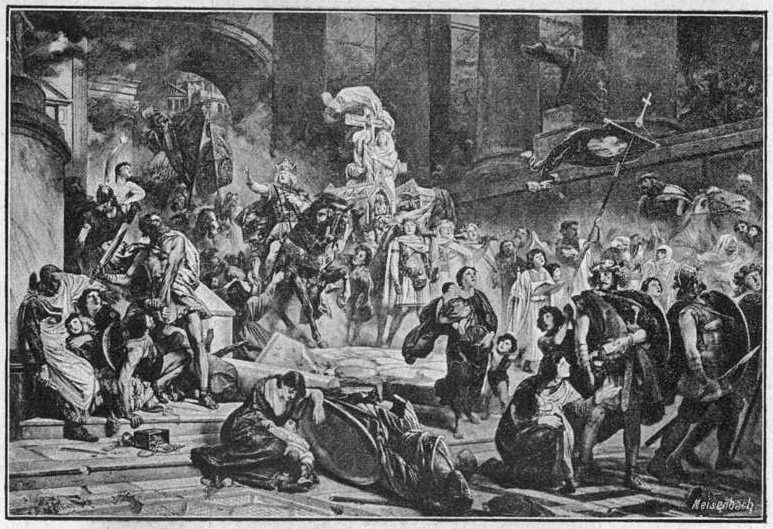

Alaric in Rome – Wilhelm Lindenschmit – Public Domain Note that in this 19th c. romanticized image, the theme of Christianity is still prominent as part of the visual representation of Rome’s fall.

Jordanes, excerpt from Romana

This account comes from Jordanes’ Romana written in Constantinople around 551 C.E. – over a century after the events described. Although it is a later account, it is more of a traditional history and gives us a sense of how later Romans remembered these events. Of Gothic origins, Jordanes served as a secretary or notary to a noble family of Goths in military life in the Eastern Empire. From scarce biographic information in the text, it also appears that he was in Constantinople at the time the text was written and that he was a Christian, perhaps even a bishop. How might his origins, political affiliations, and religious identity be seen in this historical account?1

”But after Theodosius, the lover of peace and of the Gothic race, had passed from human cares, his sons began to ruin both empires by their luxurious living and to deprive their Allies, that is to say the Goths, of the customary gifts. The contempt of the Goths for the Romans soon increased, and for fear their valor would be destroyed by long peace, they appointed Alaric king over them. He was of a famous stock, and his nobility was second only to that of the Amali, for he came from the family of the Balthi, who because of their daring valor had long ago received among their race the name Baltha, that is, The Bold. Now when this Alaric was made king, he took counsel with his men and persuaded them to seek a kingdom by their own exertions rather than serve others in idleness. In the consulship of Stilicho and Aurelian he raised an army and entered Italy, which seemed to be bare of defenders, and came through Pannonia and Sirmium along the right side. Without meeting any resistance, he reached the bridge of the river Candidianus at the third milestone from the royal city of Ravenna. …

”[W]hen the army of the Visigoths had come into the neighborhood of this city, they sent an embassy to the Emperor Honorius, who dwelt within. They said that if he would permit the Goths to settle peaceably in Italy, they would so live with the Roman people that men might believe them both to be of one race; but if not, whoever prevailed in war should drive out the other, and the victor should henceforth rule unmolested. But the Emperor Honorius feared to make either promise. So he took counsel with his Senate and considered how he might drive them from the Italian borders. He finally decided that Alaric and his race, if they were able to do so, should be allowed to seize for their own home the provinces farthest away, namely, Gaul and Spain. For at this time he had almost lost them, and moreover they had been devastated by the invasion of Gaiseric, king of the Vandals. The grant was confirmed by an imperial rescript, and the Goths, consenting to the arrangement, set out for the country given them.

”When they had gone away without doing any harm in Italy, Stilicho, the Patrician and father-in-law of the Emperor Honorius,–for the Emperor had married both his daughters, Maria and Thermantia, in succession, but God called both from this world in their virgin purity–this Stilicho, I say, treacherously hurried to Pollentia, a city in the Cottian Alps. There he fell upon the unsuspecting Goths in battle, to the ruin of all Italy and his own disgrace. When the Goths suddenly beheld him, at first they were terrified. Soon regaining their courage and arousing each other by brave shouting, as is their custom, they turned to flight the entire army of Stilicho and almost exterminated it. Then forsaking the journey they had undertaken, the Goths with hearts full of rage returned again to Liguria whence they had set out. When they had plundered and spoiled it, they also laid waste AemiIia, and then hastened toward the city of Rome along the Flaminian Way, which runs between Picenum and Tuscia, taking as booty whatever they found on either hand. When they finally entered Rome, by Alaric’s express command they merely sacked it and did not set the city on fire, as wild peoples usually do, nor did they permit serious damage to be done to the holy places. Thence they departed to bring like ruin upon Campania and Lucania, and then came to Bruttii. Here they remained a long time and planned to go to Sicily and thence to the countries of Africa.

”Now the land of the Bruttii is at the extreme southern bound of Italy, and a corner of it marks the beginning of the Apennine mountains. It stretches out like a tongue into the Adriatic Sea and separates it from the Tyrrhenian waters. It chanced to receive its name in ancient times from a Queen Bruttia. To this place came Alaric, king of the Visigoths, with the wealth of all Italy which he had taken as spoil, and from there, as we have said, he intended to cross over by way of Sicily to the quiet land of Africa. But since man is not free to do anything he wishes without the will of God, that dread strait sunk several of his ships and threw all into confusion. Alaric was cast down by his reverse and, while deliberating what he should do, was suddenly overtaken by an untimely death and departed from human cares. His people mourned for him with the utmost affection. Then turning from its course the river Busentus near the city of Consentia–for this stream flows with its wholesome waters from the foot of a mountain near that city–they led a band of captives into the midst of its bed to dig out a place for his grave. In the depths of this pit they buried Alaric, together with many treasures, and then turned the waters back into their channel. And that none might ever know the place, they put to death all the diggers. They bestowed the kingdom of the Visigoths on Athavulf his kinsman, a man of imposing beauty and great spirit; for though not tall of stature, he was distinguished for beauty of face and form.

“When Athavulf became hing, he returned again to Rome, and whatever had escaped the first sack his Goths stripped bare like locusts, not merely despoiling Italy of its private wealth, but even of its public resources. The Emperor HOnorius was powerless to resist even when his sister Placidia, the daughter of the Emperor Theodosius by his second wife, was led away captive from the city. But Athavulf was attracted by her nobility, beauty and chaste purity, and so he took her to wife in lawful marriage at Fum Julio, a city of Aemilia. When the barbarians learned of this alliance, they were the more effectually terrified, since the Empire and the Goths now seemed to be made one.” (XXIX-XXXI)2

From Jordanes, we move back in time to two responses to the events of the early 400s by people living through them, though again, neither were eyewitnesses. St. Jerome was living near Bethlehem and St. Augustine was in North Africa (modern-day Algeria), yet word of what had befallen the city obviously travelled quickly.

St. Jerome

St. Jerome is best known for his translation of the Bible into Latin which later became known as the Vulgate. He also wrote commentaries on the Gospels and is recorgnized as a Doctor of the Church for his contributions to theology. When the sack of Rome occurred, he was living an ascetic life of prayer and writing outside Bethlehem. In these excerpts from letters written around the time of Rome’s fall, Jerome laments first the ransom, then the sack of Rome. For Jerome, who or what are the enemies and why did Rome fall to them? 3

Letter 123 – to Ageruchia (409 C.E.)

”I shall now say a few words of our present miseries. A few of us have hitherto survived them, but this is due not to anything we have done ourselves but to the mercy of the Lord. Savage tribes in countless numbers have overrun all parts of Gaul. The whole country between the Alps and the Pyrenees, between the Rhine and the Ocean, has been laid waste by hordes of Quadi, Vandals, Sarmatians, Alans, Gepids, Herules, Saxons, Burgundians, Allemanni and-alas! for the commonweal!-even Pannonians. For ‘Assur also is joined with them.’ The once noble city of Moguntiacum has been captured and destroyed. In its church many thousands have been massacred. The people of Vangium after standing a long siege have been extirpated. The powerful city of Rheims, the Ambiani, the Altrebatae, the Belgians on the skirts of the world, Tournay, Spires, and Strasburg have fallen to Germany: while the provinces of Aquitaine and of the Nine Nations, of Lyons and of Narbonne are with the exception of a few cities one universal scene of desolation. And those which the sword spares without, famine ravages within. I cannot speak without tears of Toulouse which has been kept from failing hitherto by the merits of its reverend bishop Exuperius. Even the Spains are on the brink of ruin and tremble daily as they recall the invasion of the Cymry; and, while others suffer misfortunes once in actual fact, they suffer them continually in anticipation.

”I say nothing of other places that I may not seem to despair of God’s mercy. All that is ours now from the Pontic Sea to the Julian Alps in days gone by once ceased to be ours. For thirty years the barbarians burst the barrier of the Danube and fought in the heart of the Roman Empire. Long use dried our tears. For all but a few old people had been born either in captivity or during a blockade, and consequently they did not miss a liberty which they had never known. Yet who will hereafter credit the fact or what histories will seriously discuss it, that Rome has to fight within her own borders not for glory but for bare life; and that she does not even fight but buys the right to exist by giving gold and sacrificing all her substance? This humiliation has been brought upon her not by the fault of her Emperors who are both most religious men, but by the crime of a half-barbarian traitor who with our money has armed our foes against us. Of old the Roman Empire was branded with eternal shame because after ravaging the country and routing the Romans at the Allia, Brennus with his Gauls entered, Rome itself. Nor could this ancient stain be wiped out until Gaul, the birth-place of the Gauls, and Gaulish Greece, wherein they had settled after triumphing over East and West, were subjugated to her sway. Even Hannibal who swept like a devastating storm from Spain into Italy, although he came within sight of the city, did not dare to lay siege to it. Even Pyrrhus was so completely bound by the spell of the Roman name that destroying everything that came in his way, he yet withdrew from its vicinity and, victor though he was, did not presume to gaze upon what he had learned to be a city of kings. Yet in return for such insults – not to say such haughty pride – as theirs which ended thus happily for Rome, one banished from all the world found death at last by poison in Bithynia; while the other returning to his native land was slain in his own dominions. The countries of both became tributary to the Roman people. But now, even if complete success attends our arms, we can wrest nothing from our vanquished foes but what we have already lost to them. The poet Lucan describing the power of the city in a glowing passage says:

If Rome be weak, where shall we look for strength?

we may vary his words and say:

If Rome be lost, where shall we look for help?

or quote the language of Virgil:

Had I a hundred tongues and throat of bronze

The woes of captives I could not relate

Or ev’n recount the names of all the slain.

”Even what I have said is fraught with danger both to me who say it and to all who hear it; for we are no longer free even to lament our fate. and are unwilling, nay, I may even say, afraid to weep for our sufferings.”

Letter 128 – to Gaudentius (410 C.E.)

”The world sinks into ruin: yes! but shameful to say our sins still live and flourish. The renowned city, the capital of the Roman Empire, is swallowed up in one tremendous fire; and there is no part of the earth where Romans are not in exile. Churches once held sacred are now but heaps of dust and ashes; and yet we have our minds set on the desire of gain. We live as though we are going to die tomorrow; yet we build as though we are going to live always in this world. Our walls shine with gold, our ceilings also and the capitals of our pillars; yet Christ dies before our doors naked and hungry in the persons of His poor.”

Letter 127 to Principia (412 C.E.)

”Rome had been besieged and its citizens had been forced to buy their lives with gold. Then thus despoiled they had been besieged again so as to lose not their substance only but their lives. My voice sticks in my throat; and, as I dictate, sobs choke my utterance. The City which had taken the whole world was itself taken; nay more famine was beforehand with the sword and but few citizens were left to be made captives. In their frenzy the starving people had recourse to hideous food; and tore each other limb from limb that they might have flesh to eat. Even the mother did not spare the babe at her breast. In the night was Moab taken, in the night did her wall fall down. ‘O God, the heathen have come into thine inheritance; thy holy temple have they defiled; they have made Jerusalem an orchard. The dead bodies of thy servants have they given to be meat unto the fowls of the heaven, the flesh of thy saints unto the beasts of the earth. Their blood have they shed like water round about Jerusalem; and there was none to bury them.’ (Psalm 79)

”Who can set forth the carnage of that night?

What tears are equal to its agony?

Of ancient date a sovran city falls;

And lifeless in its streets and houses lie

Unnumbered bodies of its citizens.

In many a ghastly shape doth death appear.”

St. Augustine – City of God Book One, Ch. 1 – Of the adversaries of the name of Christ, whom the barbarians for Christ’s sake spared when they stormed the city.

This excerpt, similar to St. Jerome’s letters, comes from a work that was written fairly closely to events. The City of God was written in the aftermath of the destruction of Rome as a response to the arguments that swirled around about the cause of the disaster. St. Augustine chose to see the hand of God not in the destruction, but in what was saved. Look for how he describes the looting and violence here, as well as where he says it stopped.

”For to this earthly city belong the enemies against whom I have to defend the city of God. Many of them, indeed, being reclaimed from their ungodly error, have become sufficiently creditable citizens of this city; but many are so inflamed with hatred against it, and are so ungrateful to its Redeemer for His signal benefits, as to forget that they would now be unable to utter a single word to its prejudice, had they not found in its sacred places, as they fled from the enemy’s steel, that life in which they now boast themselves. Are not those very Romans, who were spared by the barbarians through their respect for Christ, become enemies to the name of Christ? The reliquaries of the martyrs and the churches of the apostles bear witness to this; for in the sack of the city they were open sanctuary for all who fled to them, whether Christian or Pagan. To their very threshold the bloodthirsty enemy raged; there his murderous fury owned a limit. Thither did such of the enemy as had any pity convey those to whom they had given quarter, lest any less mercifully disposed might fall upon them. And, indeed, when even those murderers who everywhere else showed themselves pitiless came to these spots where that was forbidden which the licence of war permitted in every other place, their furious rage for slaughter was bridled, and their eagerness to take prisoners was quenched. Thus escaped multitudes who now reproach the Christian religion, and impute to Christ the ills that have befallen their city; but the preservation of their own life—a boon which they owe to the respect entertained for Christ by the barbarians—they attribute not to our Christ, but to their own good luck. They ought rather, had they any right perceptions, to attribute the severities and hardships inflicted by their enemies, to that divine providence which is wont to reform the depraved manners of men by chastisement, and which exercises with similar afflictions the righteous and praiseworthy,—either translating them, when they have passed through the trial, to a better world, or detaining them still on earth for ulterior purposes. And they ought to attribute it to the spirit of these Christian times, that, contrary to the custom of war, these bloodthirsty barbarians spared them, and spared them for Christ’s sake, whether this mercy was actually shown in promiscuous places, or in those places specially dedicated to Christ’s name, and of which the very largest were selected as sanctuaries, that full scope might thus be given to the expansive compassion which desired that a large multitude might find shelter there. Therefore ought they to give God thanks, and with sincere confession flee for refuge to His name, that so they may escape the punishment of eternal fire—they who with lying lips took upon them this name, that they might escape the punishment of present destruction. For of those whom you see insolently and shamelessly insulting the servants of Christ, there are numbers who would not have escaped that destruction and slaughter had they not pretended that they themselves were Christ’s servants. Yet now, in ungrateful pride and most impious madness, and at the risk of being punished in everlasting darkness, they perversely oppose that name under which they fraudulently protected themselves for the sake of enjoying the light of this brief life.” 4

Questions:

- What was the purpose and nature of these three authors different accounts of events? How does this purpose and their point of view affect your understanding of events?

- Is there anything in these three accounts that gives you a sense for what Romans thought about their place in the world and their role in war by the 400s – 500s? What about the non-Roman point of view?

- What is the role of religion in these discussions of war?

Jordanes, The Gothic History Charles Christopher Mierow, translator, (Princeton: University Press, 1915), 2-10.

Jordanes, The Gothic History Charles. C. Mierow (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1908) 92-95.

A Select Library of Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church vol. VI, Philip Schaff and Henry Wace editors, (New York: The Christian Literature Company 1890) 236-7, 257, 260.

St. Augustine, The City of Godvol. 1, Marcus Dods M.A> translator (Edinburg: T&T Clark, 1871) 2-3.